PowerPoint - REL Appalachia

advertisement

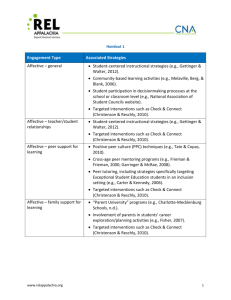

Webinar: How Do We Use Student Engagement Data to Improve Instruction? May 8, 2015 WebEx Instructions 2 WebEx instructions Attendees can provide nonverbal feedback to presenters utilizing the Feedback tool. 3 WebEx instructions Feedback options: 4 WebEx instructions Attendees should utilize the “Q&A” feature to pose questions to the speaker, panelists, and/or host. The host will hold all questions directed toward the speaker or panelists, and they will be answered during a Q&A session at the end of each discussion. 5 Welcome and Overview Elizabeth Collins Interim Director, REL Appalachia CNA Agenda 1. 2. Welcome and Overview • What is a REL? • REL Appalachia’s mission • Introductions and webinar goals Student Engagement • What it is • How to measure and monitor it • How to proactively support it and how to intervene to improve it 3. Q&A 4. Stakeholder Feedback Survey 7 What is a REL? • A REL is a Regional Educational Laboratory. • There are 10 RELs across the country. • The REL program is administered by the U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences (IES). • A REL serves the education needs of a designated region. • The REL works in partnership with the region’s school districts, state departments of education, and others to use data and research to improve academic outcomes for students. 8 What is a REL? 9 REL Appalachia’s mission • Meet the applied research and technical assistance needs of Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia. • Conduct empirical research and analysis. • Bring evidence-based information to policy makers and practitioners: – Inform policy and practice – for states, districts, schools, and other stakeholders. – Focus on high-priority, discrete issues and build a body of knowledge over time. http://www.RELAppalachia.org Follow us! @REL_Appalachia 10 Today’s speaker • James Appleton, Ph.D. • Director, Office of Research and Evaluation, Gwinnett County Public Schools (Georgia) • University of Georgia – Part-time professor • Georgia Tech – Computational Science and Engineering • Research: Student engagement • Student engagement work with Sandra Christenson, Amy Reschly, doctoral students (Lovelace, Landis, Carter, Parker, Pinzone) Main sources: • Handbook of Research on Student Engagement (2012). • Revision to “Best Practices” chapter on engagement (Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl, 2014). 11 Webinar goals • Continue a series of support by REL Appalachia on student engagement. – Webinar: What is Student Engagement and How Do We Measure It? – Workshop: Measuring and Improving Student Engagement – Workshop: Action Planning for Schoolwide Student Engagement Strategies – Materials available at www.relappalachia.org/events • Increase participants’ understanding of how student engagement can be measured. • Provide participants with best practices and tools that can increase student engagement in their schools and classrooms. 12 Monitoring and Intervening with Student Engagement Data James Appleton, Ph.D. Director, Office of Research and Evaluation Gwinnett County Public Schools What is student engagement? • Defined variously by different researchers and theorists, but there is consistency around key ideas. • A broad conceptual definition that reflects those varied perspectives: Student engagement is a measure of the extent to which a student willingly participates in schooling activities. • There is consensus among researchers and theorists that student engagement is a multidimensional construct with four elements: – Academic engagement. – Affective engagement. – Behavioral engagement. – Cognitive engagement. 14 What does existing research say about student engagement? • Student engagement is closely associated with desirable schooling outcomes. • Higher attendance, higher academic achievement, fewer disciplinary incidents, lower dropout and retention rates, higher graduation rates. (Appleton, Christenson, & Furlong, 2008; Finn, 1989, 1993; Fredricks, Blumenfeld, & Paris, 2004; Jimerson, Campos, & Grief, 2003; Jimerson, Renshaw, Stewart, Hart, & O’Malley, 2009; Shernoff & Schmidt, 2008) • Student engagement is closely associated with general measures of wellbeing. • Lower rates of health problems, lower rates of high-risk behaviors. (Carter, McGee, Taylor, & Williams, 2007; McNeely, Nonnemaker, & Blum, 2002; Patton et al., 2006) • Student engagement levels can be effectively influenced through schoolbased interventions. (Appleton, Christenson, Kim, & Reschly, 2006; Christenson et al., 2008; Fredricks, Blumenfeld, & Paris, 2004) 15 How is student engagement measured? • Three primary data collection strategies are available for measuring student engagement: • Student self-reports. • Teacher reports. • Observational measures. • Three dimensions of engagement are assessed via available instruments: • Affective/emotional: the extent of the student’s positive and negative reactions to teachers, classmates, academics, and school. • Behavioral: the student’s involvement in academic, social, and extracurricular activities. • Cognitive: the student’s level of investment in his/her learning. Note: Academic engagement is measured using traditional outcome data, such as student achievement results. (Fredericks et al., 2011) 16 How is student engagement monitored (school-level)? Average Student Engagement Ratings Percentage of Students Reporting Positive Levels 17 How is student engagement monitored (school-level)? 18 How is student engagement monitored (student-level)? 19 How is student engagement monitored (EWIS)? 20 What do we know about interventions? 21 What do we know about interventions? 22 What do we know about interventions? • IES reviews and others underscore points made earlier by Dynarski & Gleason, others: – Many programs don’t work; need good designs and evaluations. • Draw from promising practices programs and initiatives. importance of evaluating • Comprehensive, individualized, long-term interventions positively affect school completion among youth (Christenson & Thurlow, 2004). • Most promising practices and programs address student engagement in some way. 23 Engagement as remedy Given the connections between engagement and outcomes … not surprising that it is also the cornerstone of school reform (Christenson et al., 2008). • Cornerstone of high school reform initiatives. • Remedy to conditions in schools: – Bored, unmotivated, and uninvolved. • Engaging Schools (National Research Council, 2004). 24 Engagement interventions • Engagement as an organizing framework. • Important contexts for intervention (e.g., families, schools). • Universal and individualized levels. • Types interrelated. – An intervention that addresses self-regulation may also affect time on task or homework completion. Intensive Targeted Universal 25 Strategies for promoting student engagement Engagement domain Promising strategies Academic engagement Using after-school programs (tutoring, homework help), increasing home support for learning, and implementing self-monitoring interventions. Affective engagement Using problem-solving skills, setting realistic goals, and creating an active interest in learning. Behavioral engagement Devising individualized approach to attendance and participation issues, implementing programs to address skills such as problem solving and anger management, and developing behavior contracts to address individual needs. Cognitive engagement Using problem-solving skills, setting realistic goals, and creating an active interest in learning. 26 Academic engagement: Recommendations for practice • Make the most of available time – Academic engaged time (AET) is highly predictive of achievement. • Involve team and other personnel – Consultation regarding instruction and management, use tips for increasing AET, use interventions to target instructional variables (e.g., variety, match, feedback) and use of time. Source: Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl, 2014 27 Academic engagement: Recommendations for practice • Monitor failures and credits – Check against number of credits required to earn a diploma (defined by each state). Course grades—and possibly state assessments—can be used to determine credits earned. – Course failures in math or English in the 6th grade are highly predictive of failure to graduate from high school (Balfanz et al., 2007). • Teams… – Should regularly examine course grades and credits earned, and follow up to help recapture credits (retaking courses, online credit recovery, and summer school). – Should link academic engagement to early warning systems. Source: Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl, 2014 28 Academic engagement: Universal strategies • Enhance classroom managerial strategies (Gettinger & Walther, 2012). – Establish efficient and consistent classroom routines. – Decrease class and group sizes. – Minimize classroom disruptions/effectively manage off-task behavior. – Reduce transition time. • Utilize student-mediated strategies (Gettinger & Walther, 2012). – Teach meta-cognitive, self-monitoring, and study strategies to students. – Have students set their own goals for learning. – Ensure effective use of homework to enhance learning. 29 Academic engagement: Universal strategies • Facilitate home-school support for learning. – Enhance bi-directional communication with families. – Encourage parents to volunteer in the classroom (Lee & Smith, 1993). – Incorporate projects that take place in the community (Lewis, 2004). • Use a variety of interesting texts and resources. • Support student autonomy by providing choices within courses and assignments (Skinner et al., 2005). 30 Academic engagement: Individualized strategies • Utilize afterschool programs (tutoring, homework help). • Intensify partnering and communication efforts with families (e.g., homeschool notes, assignment notebooks, enrichment activities; Klem & Connell, 2004). – Ensure adequacy of educational resources in the home. – Help parents to understand and set expectations . • Implement individual self-monitoring interventions. • Foster positive teacher-student relationships for marginalized students. • Seek out and utilize college outreach programs and tutors for students (Rodriquez et al., 2004). 31 Consider • In what area do you think your school is strong in supporting academic engagement? • What area would you like to strengthen? 32 Strategies: Affective engagement Engagement domain Associated strategies Affective (general) Affective (teacher-student relationships) Affective (peer support at school) Affective (family support for learning) Student-centered instructional strategies. Community-based learning activities. Student participation in decision-making processes at the school or classroom level. Targeted interventions like Check and Connect. Student-centered instructional strategies. Targeted interventions like Check and Connect. Positive peer culture (PPC) techniques. Cross-age peer mentoring programs. Peer tutoring, including strategies specifically targeting students receiving special education services in an inclusion setting. Targeted interventions like Check and Connect. “Parent University” programs. Involvement of parents in students’ career exploration/planning activities. Targeted interventions like Check and Connect. 33 Affective engagement: Recommendations for practice • Promote belonging and bonding with school. – Belonging is associated with persistence in rigorous coursework, academic self-efficacy, stronger self-concept, and task/goal orientations (Goodenow, 1993a/b) and reduced rates of risky behaviors (McBride et al, 1995). • Teams… – Work with teachers/administrators to emphasize the importance of adultstudent connections during school day. – Ensure availability of additional support. – Implement and evaluate school programs that facilitate frequent positive contact between staff and students and use students’ engagement data to link those showing increased risk to more intensive support. Source: Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl, 2014 34 Affective engagement: Formal interventions • Seattle Social Development Project – Comprehensive intervention for elementary students to promote positive social development and improved relationships with families and schools. – Goal to prevent adolescent health and behavior problems. – 3 components: classroom management and instruction; curriculum based in cognitive-behavioral methods (self-control, social competence); and parent workshops. – Intervention effects evaluated at regular intervals through adulthood. Studies found early (1st grade) and persistent (6 years) intervention produced results (at 18) increase in school bonding and achievement, reductions in grade retention, misbehavior, violence, and sexual activity (Hawkins et al, 2007). Source: Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl, 2014 35 Affective engagement: Universal strategies • Implement advisory programs, with advisors monitoring engagement data. • Systematically build relationships/connections for all students – – Educators identify students who may not have a connection with a staff member (i.e., list all students’ names at grade levels and determine who knows the student) and match staff members and alienated students for future regular “mentor like” contact. • Address student population size through implementation of smaller learning communities. • Enhance peer connections through peer-assisted learning strategies. • Implement a mentoring program (can use college-age students). • Increase participation in extracurricular activities. 36 Strategies: Behavioral and Cognitive engagement Engagement domain Associated strategies Behavioral (general) Cognitive (control & relevance of school work) Cognitive (future aspirations and goals) Involvement of student in developing/implementing behavior plans. Positive peer culture (PPC) techniques. Student-centered instructional strategies. Community-based learning activities. Career exploration and planning activities. Student participation in decision-making processes at the school or classroom level. Targeted interventions like Check and Connect. Career exploration and planning activities. Community-based learning activities. Targeted interventions like Check and Connect. 37 Behavioral engagement: Recommendations for practice • Implement timely academic and behavior interventions. – Attendance, preparation, and behavior—even in early grades—are associated with achievement across grade levels, race, SES, and gender. – Related to later patterns of engagement/disengagement. – Absences and behavior problems interfere with learning and inhibit relationships with teachers/peers; source of stress for educators. – 3 domains: school environment, home environment, student characteristics (Goldstein, Little, & Akin-Little, 2003). • Teams… – It’s critical to intervene when attendance and behavior data indicate disengagement. – Interventions that target across domains, rather than addressing only one, are more likely to be effective. Source: Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl, 2014 38 Behavioral engagement: Recommendations for practice • Encourage and facilitate extracurricular participation. – Higher academic achievement, reduced rates of dropout and substance use, less sexual activity (for girls), better psychological adjustment (e.g., higher self-esteem), and reduced delinquent behavior (Feldman & Matjasko, 2005). • Teams…. – Pay attention to those at either end of the spectrum—low levels of participation or overscheduling. – Monitor effects of trying out and not making competitive teams. Source: Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl, 2014 39 Behavioral engagement: Formal interventions • Check & Connect – Comprehensive intervention to enhance student engagement. – Research demonstrated increased persistence, attendance, credit accrual, and school completion, as well as reduced rates of truancy, suspensions, and course failures (Christenson et al., 2012). – Personalized interventions to target all 4 subtypes of engagement Tutoring, behavior contracts, problem-solving, goal-setting, extracurricular activities. • Mentors facilitate relationships with home, school, and community. Source: Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl, 2014 40 Behavioral engagement: Individualized strategies • Develop specific behavior plans or contracts to address individual needs. • Provide intensive wrap-around services. • Provide alternative programs for students who have not completed school. • Encourage parents to monitor and supervise student behavior. • Implement student advisory programs that monitor academic and social development of secondary students (middle or high). • Implement school-to-work programs that foster success in school and relevant educational opportunities. 41 Consider At your school: • What are you doing well in terms of promoting behavioral engagement? • How do you monitor it? • Where is work needed? 42 Cognitive engagement: Recommendations for practice • Enhance self-efficacy. – Perceived capabilities for learning or performing a task. – Self-efficacy beliefs are associated with engagement in learning, effort, persistence, and achievement. • Encourage students to set challenging, reachable mastery goals; monitor progress. • Allow students to observe and work with students similar to themselves who can model target skills. • Provide students with specific feedback that praises effort and use of specific strategies in learning a skill or completing a task. Sources: Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl, 2014; Schunk & Mullen, 2012 43 Cognitive engagement: Recommendations for practice • Promote a mastery goal orientation – Helping students approach academic tasks as opportunities to learn rather than as a way to prove ability or a means of peer comparison. – TARGET (Epstein, 1989) Tasks are meaningful and relevant. Authority is shared. Students are recognized for progress and effort. Grouping is heterogeneous and flexible. Evaluation is criterion-referenced. Time is flexible in class to allow for self-pacing. Source: Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl, 2014 44 Cognitive engagement: Recommendations for practice • Teams… – Help students see failures as learning opportunities. – Give students chances to try again or improve performance based on feedback. – Consult with teachers about classroom goal structures. Focus on learning and understanding, skill development, and personal improvement rather than competition (Anderman & Patrick, 2012). Source: Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl, 2014 45 Cognitive engagement: Universal strategies • Teach, model, and promote the use of self-regulated learning strategies, such as planning, goal setting, self-monitoring of progress, strategy selection, and self-evaluation (Zimmerman, 2002). • Facilitate the goal-setting process (Greene et al., 2004; Miller & Brickman, 2004). – Help students set long-term, future-oriented goals and short-term goals that include the action steps to be taken in order to reach future goals, and taskspecific goals. – Discuss the relevance of academic tasks and skills to students’ future goals. • Promote a mastery goal orientation. Source: Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl, 2014 46 Cognitive engagement: Universal strategies • Keep the focus on understanding, skill development, and personal improvement (Anderman & Patrick, 2012). • Encourage educators and administrators to foster a mastery-oriented goal structure in the classroom and school. Remind them of the TARGET acronym (Epstein, 1989). • Provide students with choices when completing assignments. Source: Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl, 2014 47 Cognitive engagement: Individualized strategies • Enhance student’s personal belief in self through repeated contacts, goal setting, problem solving, and relationship building (e.g., Check & Connect). • Aid the student in defining goals for the future. Discuss the connection between education and those goals for the future (Miller & Brickman, 2004). • Explicitly teach cognitive and metacognitive strategies, such as managing time, chunking assignments, studying for tests, using mnemonic devices, taking notes, making outlines, and comprehending textbooks. • Implement self-monitoring interventions (e.g., graph progress toward goals). 48 Consider • How familiar were you with cognitive engagement interventions? • Give an example of how you might structure interventions for a student who seems to be both academically and cognitively disengaged. 49 Connecting other types of data 50 Connecting other types of data 51 (Gaertner & McClarty, 2015) Questions & Answers Stakeholder Feedback Survey Stakeholder Feedback Survey Please visit https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/KNY22SL to provide feedback on today’s webinar event. 54 Connect with us! www.relappalachia.org @REL_Appalachia Elizabeth Collins CollinsE@cna.org 55 Cited and other Relevant Resources Anderman, E. M., & Patrick, H. (2012). Achievement goal theory, conceptualization of ability/intelligence, and classroom climate. In A. Christenson, A. Reschly & C. Wylie (Eds.) The handbook of research on student engagement. (pp. 173–191). New York, New York: Springer Science. Andrews, D., & Lewis, M. (2004). Building sustainable futures: emerging understandings of the significant contribution of the professional learning community. Improving Schools, 7(2), 129-150. Appleton, J. J., Christenson, S. L., & Furlong, M. J. (2008). Student engagement with school: Critical conceptual and methodological issues of the construct. Psychology in the Schools, 45, 369–386. Appleton, J. J., Christenson, S. L., Kim, D., & Reschly, A. L. (2006). Measuring cognitive and psychological engagement: Validation of the Student Engagement Instrument. Journal of School Psychology, 44, 427–445. 56 Cited and other Relevant Resources Balfanz, R., Herzog, L., & Mac Iver, D. J. (2007). Preventing Student Disengagement and Keeping Students on the Graduation Path in Urban Middle-Grades Schools: Early Identification and Effective Interventions. Educational Psychologist, 42(4), 223–235. Carter, M., McGee, R., Taylor, B., & Williams, S. (2007). Health outcomes in adolescence: Associations with family, friends, and school engagement. Journal of Adolescence, 30, 51–62. Christenson, S. L., Reschly, A. L., Appleton, J. J., Berman, S., Spangers, D., & Varro, P. (2008). Best practices in fostering student engagement. In A. Thomas & J. Grimes (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology V (pp. 1099–1120). Washington, DC: National Association of School Psychologists. Christenson, S. L., Reschly, A. L., & Wylie, C. (Eds.). (2012). Handbook of Research on Student Engagement. New York: Springer. 57 Cited and other Relevant Resources Dynarski, M., & Gleason, P. (2002). How can we help? What we have learned from federal dropout prevention programs. Journal of Education for Students Placed At Risk, 7(1), 43-69. Epstein, J. L. (1989). Family structures and student motivation: A developmental perspective. In C. Ames & R. Ames (Eds.), Research on motivation in education: Vol. 3. goals and cognitions (pp. 259– 295). New York: Academic Press. Feldman, A. F., & Matjasko, J. L. (2005). The Role of School-Based Extracurricular Activities in Adolescent Development: A Comprehensive Review and Future Directions. Review of Educational Research, 57(2), 159-210. Finn, J. D. (1989). Withdrawing from school. Review of Educational Research, 59, 117–142. Finn, J. D. (1993). School engagement and students at risk. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. 58 Cited and other Relevant Resources Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. Fredricks, J., McColskey, W., Meli, J., Mordica, J., Montrosse, B., & Mooney, K. (2011). Measuring student engagement in upper elementary through high school: A description of 21 instruments (Issues & Answers Report, REL 2011–No. 098). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory Southeast. Retrieved September 13, 2013, from http://ies.ed.gove/ncee/edlabs. Gaertner, M.N., & McClarty, K.L. (2015). Middle school indicators of college readiness. Center for College & Career Success: Pearson. Gettinger, M., & Walther, M. J. (2012). Classroom strategies to enhance academic engaged time. In S.L. Christenson, A.L. Reschly & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 653-674). New York: Springer. 59 Cited and other Relevant Resources Goldstein, J.S., Little, S.G., & Akin-Little, A. (2003). Absenteeism: A review of the literature and school psychology’s role. The California School Psychologist, 8, 127-139. Goodenow, C. (1993a). The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: Scale development and educational correlates. Psychology in the Schools, 30, 79–90. Goodenow, C. (1993b). Classroom belonging among early adolescent students: Relationship to motivation and achievement. Journal of Early Adolescence, 13, 21–43. Greene, B. A., Miller, R. B., Crowson, H. M., Duke, B. L., & Akey, K. L. (2004). Predicting high school students’ cognitive engagement and achievement: Contributions of classroom perceptions and motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 29, 462– 482. 60 Cited and other Relevant Resources Hawkins, J. D., Smith, B. H., Hill, K. G., Kosterman, R., Catalano, R. F., & Abbott, R. D. (2007). Promoting social development and preventing health and behavior problems during the elementary grades: Results from the Seattle Social Development Project. Victims & Offenders, 2, 161–181. Jimerson, S., Campos, E., & Grief, J. (2003). Toward an understanding of definitions and measures of school engagement and related terms. The California School Psychologist, 8, 7–27. Jimerson, S., Renshaw, T., Stewart, K., Hart, S., & O’Malley, M. (2009). Promoting school completion through understanding school failure: A multi-factorial model of dropping out as a developmental process. Romanian Journal of School Psychology, 2, 12–29. Klem, A. M., & Connell, J. P. (2004). Relationships Matter: Linking Teacher Support to Student Engagement and Achievement. Journal of School Health, 7(74). 61 Cited and other Relevant Resources Lee, V.E., & Smith, J.B. (1993). Effects of school restructuring on the achievement and engagement of middle-grade students. Sociology of Education, 66, 164-187. McBride, C. M., Curry, S. J., Cheadle, A., Anderman, C., Wagner, E. H., Diehr, P., & Psaty, B. (1995). School-level application of a social bonding model to adolescent risktaking behavior. Journal of School Health, 65, 63–68. McNeely, C. A., Nonnemaker, J. M., & Blum, R. W. (2002). Promoting school connectedness: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Journal of School Health, 72, 138–146. Miller, R. B., & Brickman, S. J. (2004) A Model of Future-Oriented Motivation and Self-Regulation. Educational Psychology Review, 16(1). 62 Cited and other Relevant Resources National Research Council and the Institute of Medicine. (2004). Engaging schools: Fostering high school students’ motivation to learn. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Patton, G. C., et al. (2006). Promoting social inclusion in schools: A grouprandomized trial of effects on student health risk behavior and wellbeing. American Journal of Public Health, 96, 1582–1587. Reschly, A.L., Appleton, J.J., & Pohl, A. (2014). Best practices in fostering student engagement. In A. Thomas and P. Harrison (Eds.) Best practices in school psychology – 6th Ed. Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists. Schunk, D. H., & Mullen, C. A. (2012). Self-Efficacy as an Engaged Learner. In S. L Christenson et al (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Student Engagement. New York: Springer. 63 Cited and other Relevant Resources Shernoff, D., & Schmidt, J. (2008). Further evidence of an engagementachievement paradox among U.S. high school students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(5), 564–580. Skinner, C. H., Pappas, D. N., & Davis, K. A. (2005). Enhancing academic engagement: Providing opportunities for responding and influencing students to choose to respond. Psychology in the Schools, 42(4), 389–403. Zimmerman, B.J. (2002). Achieving self-regulation: The trial and triumph of adolescence. In F. Pajares & T. Urdan (Eds.), Academic motivation of adolescents (Vol. 2, pp. 1–27). Greenwich, CT: Information Age. 64