What Is Student Engagement?

advertisement

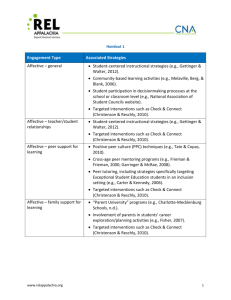

Action Planning for Schoolwide Student Engagement Strategies November 20, 2014 Roanoke, West Virginia Welcome and Overview Lydotta Taylor, Ed.D. Alliance Lead, REL Appalachia What is a REL? • A REL is a regional educational laboratory. • There are 10 RELs across the country. • The REL program is administered by the U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences (IES). • A REL serves the education needs of a designated region. • The REL works in partnership with the region’s school districts, state departments of education, and others to use data and research to improve academic outcomes for students. 3 What is a REL? 4 REL Appalachia’s mission • Meet the applied research and technical assistance needs of Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia. • Conduct empirical research and analysis. • Bring evidence-based information to policymakers and practitioners: – Inform policy and practice—for states, districts, schools, and other stakeholders. – Focus on high-priority, discrete issues and build a body of knowledge over time. http://www.RELAppalachia.org Follow us! @REL_Appalachia 5 Workshop goals • Define student engagement. • Map the West Virginia School Climate Survey to the student engagement construct. • Map the West Virginia School Climate Survey to promising strategies from the student engagement literature. • Create and share action plans for improving student engagement in your schools. 6 What Is Student Engagement? James Appleton, Ph.D. Director of Research and Evaluation, Gwinnett County (Georgia) Public Schools, and Part-time Professor, University of Georgia Introductions • Gwinnett County (Georgia) Public Schools – Director, Office of Research and Evaluation • University of Georgia – Part-time professor • Georgia Tech – Computational Science and Engineering • Research: Student engagement • Check & Connect – 2002-03 Mentor Research • Student engagement work with Sandra Christenson, Amy Reschly, doctoral students (Lovelace, Landis, Carter, Parker, Pinzone) Main Sources: • Handbook of Research on Student Engagement (2012). • Revision to “Best Practices” chapter on engagement (Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl, 2014). 8 Introductions University of Georgia & Gwinnett County Public Schools • • • • 165,000 students in 2012-13 (growing: ~ 2,300/yr) 14th largest U.S. school district 77 elementary, 26 middle, 19, high, 4 charter, and 6 other schools 56% of students qualified for free or reduced price lunch 10% Asian, 30% Black, 26% Hispanic, 29% White, 4% Other. 9 Discussion questions • What does the term “student engagement” mean to you? • To what extent is student engagement a concern in your school or district? • In what ways and to what extent is your school or district working to promote student engagement? • In what ways are you using the results obtained from the West Virginia School Climate Survey? 10 What is student engagement? • Student engagement has been defined variously by different researchers and theorists, but there is consistency around key ideas. • A broad conceptual definition that reflects those varied perspectives: Student engagement is a measure of the extent to which a student willingly participates in schooling activities. (Appleton, Christenson, & Furlong, 2008) • There is consensus among researchers and theorists that student engagement is a multidimensional construct consisting of three subtypes (Appleton et al., 2008; Fredricks et al., 2011): – Affective engagement. – Behavioral engagement (Academic). – Cognitive engagement. 11 What does research say about student engagement? • Student engagement is closely associated with desirable schooling outcomes (higher attendance, higher academic achievement, fewer disciplinary incidents, lower dropout rates, higher graduation rates). (Appleton et al., 2008; Finn, 1989, 1993; Fredricks, Blumenfeld, & Paris, 2004; Jimerson, Campos, & Grief, 2003; Jimerson, Renshaw, Stewart, Hart, & O’Malley, 2009; Shernoff & Schmidt, 2008) • Student engagement is closely associated with general measures of well-being (lower rates of health problems, lower rates of high-risk behaviors). (Carter, McGee, Taylor, & Williams, 2007; McNeely, Nonnemaker, & Blum, 2002; Patton et al., 2006) • Student engagement levels can be effectively influenced through school-based interventions. (Appleton, Christenson, Kim, & Reschly, 2006; Christenson et al. 2008; Fredricks et al., 2004) 12 Student engagement: Background • First appeared in the literature 25 years ago: – Mosher & MacGowan, 1985. • Evolving conceptualization. – Academic Engaged Time to “Meta-Construct” (Fredricks et al., 2004). • Interest in engagement international, continues to grow. – Associations with outcomes across academic, behavioral, and social/emotional domains. – Amenable to intervention. – Resonates with educators: ties to achievement; depicts what they see in schools. ~ Enhancing student learning and outcomes. Source: Reschly & Christenson, 2012 13 Student engagement: Background Engagement is the cornerstone of the primary theory of dropout/school completion and is the basis of our most promising interventions. • Finn, 1989. • Participation-Identification Model – Indicators of withdrawal and engagement. – Belonging, Identification, Relationships. 14 Developmental processes of engagement • Successful engagement changes with age – more opportunities and responsibilities. • Cycle over many years: – For many students, cycle works as it should: have attitudes, skills, behaviors needed to be successful. Participate–success–value–participate. – For others, don’t have the attitudes, skills, behaviors needed to be successful, so cycle breaks down over time poorer performance and withdrawal. OR – Encounter significant academic problems, difficulty interacting with teachers, or develop relationships with disengaged peers (Finn & Zimmer, 2012). 15 Why is this important? • Pathways to dropout from early childhood. • Long-term effectiveness (achievement, dropout) of preschool programs like Perry Preschool and Chicago Parent-Child Centers (participationsuccess-valuing cycle at school entry). • We can predict dropout from early elementary school based on variables such as attendance, behavior, academic performance (especially reading), and attachment to school. 16 Why is this important? • Many of the serious warning signs present later in high school – and middle school – such as failing courses and high-stakes assessments, significant behavior problems, were preceded by less-severe forms of withdrawal (disengagement) in elementary and middle school. = Engagement associated with and predictive of important proximal and distal outcomes • Patterns of engagement over time (come back to this later – important for screening and intervention). – General declines within and across school years. – Two longitudinal studies: ~ 30% stable (high or low levels of engagement). 17 Why is this important? • Behavioral engagement is among the most robust predictors of proximal (achievement) and distal (completion) outcomes BUT … – Things such as affective (psychological) and cognitive engagement indirectly relate to those same outcomes through their effect on behavior. – What is sometimes referred to as the “Other ABCs”: Autonomy. Belonging. Competence (theme across disciplines). 18 Why is this important? — Intervention Status vs. Alterable Variables: • Students less likely to complete school if: – Of Hispanic, Native American, or Black descent. – Low-SES background. – Live in single-parent home. – Have a sibling or parent who dropped out. – Have disabilities. – Live in the Southern and Western regions of the U.S. • Christenson’s (2008) Demographic/Functional Risk Distinction: – Race-ethnicity data — Hispanic (Event) 6.0% (status) 21.4% (status comp) 72.7%. – Functional risk is information that may be used to directly inform intervention efforts (e.g., attendance, behavioral difficulties -> engagement). 19 Turn and talk • Describe one student who has demographic risk but functional strengths. • Describe another student with functional risk but demographic strengths. • How do these differences affect your intervention approaches? 20 What do we know about interventions? “Currently, we know considerably more about who drops out than we do about the essential intervention components for whom and under what conditions.” Christenson et al., 2001 • Still lagging behind in delineating evidence-based dropout prevention strategies and programs. – Gaps and weaknesses of intervention noted in various reviews (Christenson et al., 2000; Dynarski & Gleason, 2002; Prevatt & Kelly, 2003). BUT ... – Promising practice and programs. 21 What do we know about interventions? 22 What do we know about interventions? 23 What do we know about interventions? 24 What do we know about interventions? • IES reviews and others underscore points made earlier by Dynarski & Gleason, others: – Many programs that don’t work; need for good designs and evaluations. • Draw from promising practices programs and initiatives. importance of evaluating • Comprehensive, individualized, long-term interventions positively affect school completion among youth (Christenson & Thurlow, 2004). • Most promising practices and programs address student engagement in some way. 25 More engagement-intervention caveats • Amenability to intervention. – Mediation between contexts and outcomes. • Importance of contexts. 26 More engagement-intervention caveats Source: Reschly & Christenson, 2012 27 More engagement-intervention caveats Engagement is the organizing framework for linking contexts – home school peers – to behaviors & experiences that are, in turn, related to important outcomes. Source: Reschly & Christenson, 2012 28 More engagement-intervention caveats Engagement is alterable. Source: Reschly & Christenson, 2012 29 More engagement-intervention caveats These types are related – Belonging may promote more effort and participation. Teaching practices that promote strategy use or self-regulation may facilitate greater time on task (academic). Source: Reschly & Christenson, 2012 30 Engagement as remedy Given the connections between engagement and outcomes … not surprising that it is also the cornerstone of school reform (Christenson et al., 2008). • Cornerstone of high school reform initiatives. • Remedy to conditions in schools: – Bored, unmotivated, and uninvolved. • Engaging Schools (National Research Council, 2004). 31 Engagement as remedy A common theme among effective practices is that they have a positive effect on the motivation of individual students because they address underlying psychological variables such as competence, control, beliefs about the value of education, and a sense of belonging. ... National Research Council, 2004, p. 212 32 Engagement as remedy ... In brief, effective schools and teachers promote students’ understanding of what it takes to learn and confidence in their capacity to succeed in school by providing challenging instruction and support for meeting high standards, and by conveying high expectations for their students’ success. ... National Research Council, 2004, p. 212 33 Engagement as remedy ... They provide choices and they make the curriculum and instruction relevant to adolescents’ experiences, cultures, and long-term goals, so that students see some value in what they are doing in school. ... National Research Council, 2004, p. 212 34 Engagement as remedy ... Finally, they promote a sense of belonging by personalizing instruction, showing an interest in students’ lives, and creating a supportive, caring social context. National Research Council, 2004, p. 212 35 Engagement involves … • The “Other ABCs”: – Autonomy – Belonging – Competence I want to … I belong … I can … Sources: Christenson & Thurlow, 2004; Finn, 1989; Newmann, 1992 36 Engagement pyramid Intensive Targeted Universal 37 Summary and questions? • Student engagement of interest across disciplines, nationalities, researchers, and educators. • General agreement that it involves some aspects of students’ behavior, emotion, and cognition. • Associated with proximal and distal outcomes in achievement, socialemotional, and behavioral domains. – Not just dropout. – Associated with academic achievement, lower-risk health and sexual behaviors, social-emotional well-being, and long-term outcomes such as work success. • Developmental patterns of engagement/disengagement over time. • Amenable to intervention. • Mediator; links contexts to outcomes. 38 Mapping the WV School Climate Survey to the Student Engagement Construct Overview • The West Virginia School Climate Survey. • Student engagement domains measured in the West Virginia School Climate Survey. 40 The WV School Climate Survey • Provided at no cost to West Virginia schools and districts by the West Virginia Department of Education. • Online survey offered twice per year (fall and spring). • Consists of three interrelated surveys: – Student (separate versions for elementary and middle/high school students). – School staff. – Parent/caregiver. • This workshop focuses on the student survey for middle/high school students and the Engagement domain within that survey. • For the purpose of mapping survey items to the student engagement literature, the workshop relies on the student engagement construct and terms used in the Student Engagement Instrument (SEI) developed by Appleton and colleagues (2006). 41 The WV School Climate Survey (MS/HS students) • Engagement domain (as identified in Fredricks et al. 2011): – Relationships (13 items). – Respect for Diversity (4 items). – Participation (12 items). • Some of the items under Environment: Academic and Disciplinary, as well as Safety: Emotional Safety, could be also categorized under the Engagement domain. – As time allows, they will be discussed. 42 WV-SCS: Engagement Domain – Relationships • I am happy to be at this school. • The teachers at this school treat students fairly. At my school, there is a teacher or some other adult who ... – really cares about me. – tells me when I do a good job. – notices when I’m not there. • Adults at this school treat all students with respect. • I have been disrespected by an adult at this school because of my race, ethnicity, or culture. 43 WV-SCS: Engagement Domain – Relationships (cont’d) Outside of my home or school, there is an adult ... – who really cares about me. – who notices when I am upset about something. – whom I trust. • How much of a problem at your school is lack of respect of staff by students? • Have relationships among students gotten better, gotten worse, or stayed about the same since last year? • Have relationships among students and staff gotten better, stayed about the same, or gotten worse since last year? 44 WV-SCS: Engagement Domain – Respect for Diversity • My class lessons include examples of my racial, ethnic, or cultural background. • There is a lot of tension in this school between people of different cultures, races, or ethnicities. • How much of a problem at your school is racial/ethnic conflict among students? • Has respect for racial, ethnic, or cultural diversity gotten better, stayed about the same, or gotten worse since last school year? 45 WV-SCS: Engagement Domain – Participation • I feel close to people at this school. • I feel like I am a part of this school. • At school, I do things that make a difference. • After high school, it is likely that I will attend a technical or vocational school. • After high school, it is likely that I will serve in the armed services. • After high school, it is likely that I will graduate from a two-year college program. 46 WV-SCS: Engagement Domain – Participation (cont’d) • After high school, it is likely that I will graduate from a four-year college. • It is likely that I will attend graduate school or professional school after college. • During the past 12 months, about how many times did you skip school or cut classes? • How much would your family care if you quit school? • The school is a little or a lot better than last year in terms of being a supportive academic environment. • Students’ physical or mental health is a little or a lot better than last year. 47 Engagement research and the WV School Climate Survey Relationships: • • • • • • • I am happy to be at this school. Affective engagement (general) The teachers at this school treat students fairly. Affective engagement (teacherstudent relationships) At my school, there is a teacher or some other adult who really cares about me. Affective engagement (teacher-student relationships) At my school, there is a teacher or some other adult who tells me when I do a good job. Affective engagement (teacher-student relationships) At my school, there is a teacher or some other adult who notices when I’m not there. Affective engagement (teacher-student relationships) Adults at this school treat all students with respect. Affective engagement (teacher-student relationships) I have been disrespected by an adult at this school because of my race, ethnicity, or culture. Affective engagement (teacher-student relationships) 48 Engagement research and the WV School Climate Survey Relationships (cont’d): • • • • • • Outside of my home or school, there is an adult who really cares about me. Affective engagement (general) Outside of my home or school, there is an adult who notices when I am upset about something. Affective engagement (general) Outside of my home or school, there is an adult whom I trust. Affective engagement (general) How much of a problem at your school is lack of respect of staff by students? Affective engagement (teacher-student relationships) Have relationships among students gotten better, gotten worse, or stayed about the same since last year? Affective engagement (peer support at school) Have relationships among students and staff gotten better, stayed about the same, or gotten worse since last year? Affective engagement (teacher-student relationships) 49 Engagement research and the WV School Climate Survey Respect for Diversity: • • • • My class lessons include examples of my racial, ethnic, or cultural background. Cognitive engagement (control & relevance of school work) There is a lot of tension in this school between people of different cultures, races, or ethnicities. Affective engagement (general) How much of a problem at your school is racial/ethnic conflict among students? Affective engagement (general) Has respect for racial, ethnic, or cultural diversity gotten better, stayed about the same, or gotten worse since last school year? Affective engagement (general) 50 Engagement research and the WV School Climate Survey Participation: • • • • • • I feel close to people at this school. Affective engagement (general) I feel like I am a part of this school. Affective engagement (general) At school, I do things that make a difference. Cognitive engagement (control & relevance of school work) After high school, it is likely that I will attend a technical or vocational school. Cognitive engagement (future aspirations & goals) After high school, it is likely that I will serve in the armed services. Cognitive engagement (future aspirations & goals) After high school, it is likely that I will graduate from a two-year college program. Cognitive engagement (future aspirations & goals) 51 Engagement research and the WV School Climate Survey Participation (cont’d): • • • • • • After high school, it is likely that I will graduate from a four-year college. Cognitive engagement (future aspirations & goals) It is likely that I will attend graduate school or professional school after college. Cognitive engagement (future aspirations & goals) During the past 12 months, about how many times did you skip school or cut classes? Behavioral engagement (general) How much would your family care if you quit school? Affective engagement (family support for learning) The school is a little or a lot better than last year in terms of being a supportive academic environment. Affective engagement (general) Students physical or mental health is a little or a lot better than last year. Affective engagement (general) 52 Engagement research and the WV School Climate Survey Summary of mapping results: • Affective engagement (general): 11 WVSCS items • Affective engagement (teacher-student relationships): 8 WVSCS items • Affective engagement (peer support at school): 1 WVSCS item • Affective engagement (family support for learning): 1 WVSCS item • Behavioral engagement (general): 1 WVSCS item • Cognitive engagement (control & relevance of school work): 2 WVSCS items • Cognitive engagement (future aspirations & goals): 5 WVSCS items 53 Engagement research and the WV School Climate Survey Safety: Emotional Safety 7e I feel safe in my school. (AE-TSR) 24h avoided school activities for fear of being attacked or harmed? (AE\BE) 28 During the past 30 days, did you avoid going to school on one or more days because you felt unsafe at school, or on your way to and from school? (AE\BE) 54 Engagement research and the WV School Climate Survey Environment: Academic Environment At my school, there is a teacher or some other adult who ... 8d always wants me to do my best. (AE-TSR) 8e listens to me when I have something to say. (AE-TSR) 8f believes I will be a success. (AE-TSR) 9a At school, I do interesting activities. (CE-CRSW) 9b I help decide things like class activities or rules. (CE-CRSW) 10e Adults at this school encourage me to work hard so I can be successful in college or at the job I choose. (CE-FG) 10f My teachers work hard to help me with my schoolwork when I need it. (AE-TSR) 10g Teachers show how classroom lessons are helpful to students in real life. (CECRSW) 55 Engagement research and the WV School Climate Survey Environment: Academic Environment (cont’d) 10h Teachers give students a chance to take part in classroom discussions or activities. (AE-TSR) 10i Students at this school are motivated to learn. (AE-PSS) 10j This school promotes academic success for all students. (AE-TSR) 10k This school is a supportive and inviting place for students to learn. (AE-TSR) Outside of my home and school, there is an adult ... 12b who tells me when I do a good job. (AE-FSL) 12d who believes that I will be a success. (AE-FSL) 12e who always wants me to do my best. (AE-FSL) Environment: Disciplinary Environment 10l All students are treated fairly when they break school rules. (AE-TSR) 56 Mapping the WV School Climate Survey to Promising Strategies from the Student Engagement Literature Overview • Describe promising strategies in the research literature on student engagement. • How the promising strategies align with the student engagement domains included in the West Virginia School Climate Survey. 58 Strategies for promoting student engagement Engagement domain Promising strategies Academic engagement Using after-school programs (tutoring, homework help), increasing home support for learning, and implementing self-monitoring interventions. Affective engagement Using problem-solving skills, setting realistic goals, and creating an active interest in learning. Behavioral engagement Devising individualized approach to attendance and participation issues, implementing programs to address skills such as problem solving and anger management, and developing behavior contracts to address individual needs. Cognitive engagement Using problem-solving skills, setting realistic goals, and creating an active interest in learning. 59 Strategies for promoting student engagement Engagement domain Promising strategies Academic engagement Using after-school programs (tutoring, homework help), increasing home support for learning, and implementing self-monitoring interventions. Affective engagement (21 WVSCS items) Using problem-solving skills, setting realistic goals, and creating an active interest in learning. Behavioral engagement (1 WVSCS item) Devising individualized approach to attendance and participation issues, implementing programs to address skills such as problem solving and anger management, and developing behavior contracts to address individual needs Cognitive engagement (7 WVSCS items) Using problem-solving skills, setting realistic goals, and creating an active interest in learning. 60 Student engagement and the WV School Climate Survey 61 Strategies Engagement domain Associated strategies Affective (general) Affective (teacher-student relationships) Affective (peer support at school) Affective (family support for learning) Student-centered instructional strategies. Community-based learning activities. Student participation in decision-making processes at the school or classroom level. Targeted interventions like Check and Connect. Student-centered instructional strategies. Targeted interventions like Check and Connect. Positive peer culture (PPC) techniques. Cross-age peer mentoring programs. Peer tutoring, including strategies specifically targeting students receiving special education services in an inclusion setting. Targeted interventions like Check and Connect. “Parent University” programs. Involvement of parents in students’ career exploration/planning activities. Targeted interventions like Check and Connect. 62 Strategies Engagement domain Associated strategies Behavioral (general) Cognitive (control & relevance of school work) Cognitive (future aspirations & goals) Involvement of student in developing/implementing behavior plans. Positive peer culture (PPC) techniques. Student-centered instructional strategies. Community-based learning activities. Career exploration and planning activities. Student participation in decision-making processes at the school or classroom level. Targeted interventions like Check and Connect. Career exploration and planning activities. Community-based learning activities. Targeted interventions like Check and Connect. 63 But first … • Observable Engagement • Internal Engagement Academic Cognitive e.g., Value & relevance of school work Behavioral Affective e.g., Belonging, identification, connectedness Source: Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl 2014 64 Effectiveness 65 Assessment Internal (high inference) Observable (low inference) Type of Engagement Indicators Type of Engagement Indicators Academic • • Time on task. Accrual of credits. Affective • • Belonging. Identification with School. Behavioral • • • Attendance. Participation. Preparation for class/school. Cognitive • Value/Relevance of education. Self-regulation. Goal-setting Assessment/ Tracking: Compiled from commonly collected School Data • • Assessment/ Tracking: Mainly student self-reports, with possible supplements of teacher, peer, or parent report. Source: Reschly, Appleton, & Christenson, 2008 66 Turn and talk Think of the types of engagement data you have at your school: • Do you have all 4 subtypes? • How easily accessible are they? • How often do you use them? 67 Engagement interventions • Recall engagement as a “Meta-Construct.” • Organizing framework. • Important contexts for assessment and intervention (e.g., families, schools). • Universal and individualized levels. • Types interrelated. Intensive Targeted Universal – An intervention that addresses self-regulation may also affect time on task or homework completion. 68 Academic engagement: recommendations for practice • Make the most of available time – Academic engaged time highly predictive of achievement. – Large portions of day not devoted to instruction + many classrooms with low levels of AET even within allotted instructional time (Gettinger & Walther, 2012). • Team and other personnel – Consultation regarding instruction and management, tips for increasing AET; interventions to target instructional variables (e.g., variety, match, feedback) and use of time. Source: Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl, 2014 69 Academic engagement: recommendations for practice • Monitor failures and credits – # of credits, defined by each state, required to earn a diploma. Course grades & possibly state assessments used to determine credits earned. – Course failures in math or English in the 6th grade highly predictive of failure to graduate from HS (Balfanz et al., 2007). • Teams…. – Should regularly examine course grades and credits earned; follow-up to help recapture credits (retaking courses, on-line credit recovery, & summer school). – Link to early warning systems. Source: Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl, 2014 70 Turn and talk • Give an example of an area where you think you are strong in supporting academic engagement. • Share another area you’d like to strengthen, along with a couple of ideas on ways you could accomplish that. 71 Academic engagement: Universal strategies • Enhance classroom managerial strategies (Gettinger & Walther, 2012). – Establish efficient and consistent classroom routines. – Decrease class and group sizes. – Minimize classroom disruptions/effectively manage off-task behavior. – Reduce transition time. • Utilize student-mediated strategies (Gettinger & Walther, 2012). – Teach meta-cognitive, self-monitoring, and study strategies to students. – Have students set their own goals for learning. – Ensure effective use of homework to enhance learning. 72 Academic engagement: Universal strategies (cont’d) • Facilitate home-school support for learning. – Provide home support for learning strategies to content area. – Enhance bi-directional communication with families. – Encourage parents to volunteer in the classroom (Lee & Smith, 1993). – Incorporate projects that take place in the community (Lewis, 2004). • Use a variety of interesting texts and resources. • Support student autonomy by providing choices within courses and assignments (Skinner et al., 2005). 73 Academic engagement: Individualized strategies • Utilize afterschool programs (tutoring, homework help). • Intensify partnering and communication efforts with families (e.g., homeschool notes, assignment notebooks, enrichment activities; (Klem & Connell, 2004). – Ensure adequacy of educational resources in the home. – Help parents to understand and set expectations . • Implement individual self-monitoring interventions. • Foster positive teacher-student relationships for marginalized students. • Seek out and utilize college outreach programs and tutors for students (Rodriquez et al., 2004). 74 Commonly asked questions • Middle and high school students failing (combination – some can’t do/some won’t do). • How do you keep a student academically engaged when they are so far behind their peers? 75 Behavioral engagement: Recommendations for practice • Implement timely academic and behavior interventions. – Attendance, preparation, and behavior – even in early grades – associated with achievement across grade levels, race, SES, and gender. – Related to later patterns of engagement/disengagement. – Absences and behavior problems interfere with learning and inhibit relationships with teachers/peers; source of stress for educators. – 3 domains: school environment, home environment, student characteristics (Goldstein, Little, & Akin-Little, 2003). • Teams…. – Critical to intervene when attendance and behavior data indicate disengagement. – Interventions that target across domains rather than one more likely to be effective. Source: Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl, 2014 76 Behavioral engagement: Recommendations for practice • Encourage and facilitate extracurricular participation. – Higher academic achievement, reduced rates of dropout and substance use, less sexual activity (for girls), better psychological adjustment (e.g., higher self esteem), and reduced delinquent behavior --- Feldman & Matjasko (2005). • Teams…. – Pay attention to those at either end of the spectrum – low levels of participation and overscheduling. – Effects of trying out and not making competitive teams. Source: Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl, 2014 77 Behavioral engagement: Formal interventions • Check & Connect – Comprehensive intervention to enhance student engagement. – Research demonstrated increased persistence, attendance, credit accrual, and school completion as well as reduced rates of truancy, suspensions, and course failures (Christenson et al., 2012). – Personalized interventions to target all 4 subtypes of engagement Tutoring, behavior contracts, problem-solving, goal setting, extracurricular activities. • Mentors facilitate relationships with home, school, and community. Source: Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl, 2014 78 Turn and talk At your school: • What are you doing well in terms of promoting behavioral engagement? • How do you monitor it? • Where is work needed? 79 Behavioral engagement: Individualized strategies • Develop specific behavior plans or contracts to address individual needs. • Provide intensive wrap-around services. • Provide alternative programs for students who have not completed school. • Encourage parents to monitor and supervise student behavior. • Implement student advisory programs that monitor academic and social development of secondary students (middle or high) . • Implement school-to-work programs that foster success in school and relevant educational opportunities. 80 Cognitive engagement: Recommendations for practice • Enhance Self-Efficacy. – Perceived capabilities for learning or performing a task. – Self-efficacy beliefs associated with engagement in learning, effort, persistence, and achievement (Schunk & Mullen, 2012). • Schunk & Mullen (2012) – Encourage students to set challenging, reachable mastery goals; monitor progress. – Allow students to observe and work with students similar to themselves who can model target skills. – Provide students with specific feedback that praises effort and use of specific strategies in learning a skill or completing a task. • Teams… – Implementing the strategies/sharing with educators. Source: Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl, 2014 81 Cognitive engagement: Recommendations for practice • Promote a Mastery Goal Orientation – Helping students approach academic tasks as opportunities to learn rather than to prove ability or peer comparison. – TARGET (Epstein, 1989) Tasks are meaningful and relevant. Authority is shared. Students are recognized for progress and effort. Grouping is heterogeneous and flexible. Evaluation is criterion-referenced. Time is flexible in class to allow for self-pacing. Source: Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl, 2014 82 Cognitive engagement: Recommendations for practice • Teams…. – Help students see failures as learning opportunities. – Give students chances to try again or improve performance based on feedback. – Consult with teachers re. classroom goal structures. Focus on learning and understanding, skill development, and personal improvement rather than competition (Anderman & Patrick, 2012). Source: Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl, 2014 83 Turn and talk • How familiar were you with cognitive engagement interventions? • Give an example of how you might structure interventions for a student who seems to be both academically and cognitively disengaged. 84 Cognitive engagement: Universal strategies • Teach, model, and promote the use of self-regulated learning strategies such as planning, goal setting, self-monitoring of progress, strategy selection, and self-evaluation (Zimmerman, 2002). • Facilitate the goal setting process (Greene et al., 2004; Miller & Brickman, 2004). – Help students set long-term, future-oriented goals and short-term goals that include the action steps to be taken in order to reach future goals, and taskspecific goals. – Discuss the relevance of academic tasks and skills to students’ future goals. • Promote a mastery goal orientation. Source: Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl, 2014 85 Cognitive engagement: Universal strategies • Keep the focus on understanding, skill development, and personal improvement (Anderman & Patrick, 2012). • Encourage educators and administrators to foster a mastery-oriented goal structure in the classroom and school. Remind them of the TARGET acronym (Epstein, 1989). • Provide students with choices when completing assignments. Source: Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl, 2014 86 Cognitive engagement: Individualized strategies • Enhance student’s personal belief in self through repeated contacts, goal setting, problem solving, and relationship building (e.g., Check & Connect). • Aid the student in defining goals for the future. Discuss the connection between education and those goals for the future (Miller & Brickman, 2004). • Explicitly teach cognitive and metacognitive strategies such as managing time, chunking assignments, studying for tests, using mnemonic devices, taking notes, making outlines, and comprehending textbooks. • Implement self-monitoring interventions (e.g., graph progress toward goals). 87 Affective engagement: Recommendations for practice • Promote belonging and bonding with school. – Belonging associated with persistence in rigorous coursework, academic selfefficacy, stronger self-concept and task goal orientations (Goodenow, 1993a/b) and reduced rates of risky behaviors (McBride et al, 1995). • Teams… – Work with teachers/administrators to emphasize the importance of adultstudent connections during school day. – Ensure availability of additional support. – Implement and evaluate school programs that facilitate frequent positive contact between staff and students and use students’ engagement data to link those showing increased risk to more intensive support. Source: Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl, 2014 88 Affective engagement: Formal interventions • Seattle Social Development Project. – Comprehensive intervention for elementary students to promote positive social development and improved relationships with families and schools. – Goal to prevent adolescent health and behavior problems. – 3 components: classroom management and instruction; curriculum based in cognitive-behavioral methods (self-control, social competence); parent workshops. – Intervention effects evaluated at regular intervals through adulthood. Studies found early (1st grade) and persistent (6 years) intervention produced results (at 18) ~ increase in school bonding and achievement, reductions in grade retention, misbehavior, violence, and sexual activity (Hawkins et al, 2007). Source: Reschly, Appleton, & Pohl, 2014 89 Affective engagement: Universal strategies • Implement advisory programs with advisors monitoring engagement data. • Systematically build relationships/connections for all students – – Educators identify students who may not have a connection with a staff member (i.e., list all students names at grade levels and determine who knows the student) and match staff members and alienated students for future regular “mentor like” contact. • Address size through implementation of smaller learning communities. • Enhance peer connections through peer-assisted learning strategies. • Implement a mentoring program (use of college age students). • Increase participation in extracurricular activities. 90 Lunch Developing an Action Plan for Promoting Student Engagement Overview • Review school reports to identify needs/priorities. • Identify strategies aligned to needs/priorities. • Develop an action plan for addressing needs/priorities. 93 WV School Climate Survey reports • Overview of report content and structure (using the individual school reports of participants). 94 Student engagement and the WV School Climate Survey 95 Action planning Action step Timeframe Resources / support needed Responsible person(s) Progress status Use WV-SCS reports to identify students for different tiers of intervention. Consider specific strategies and/or interventions. Implement the planned strategies and/or interventions, 1) collecting data along the way to see if interventions are well-implemented and working, 2) collecting summary data on entire effort. Assess and make adjustments as needed. 96 Break Sharing Action Plans Sharing action plans • Share in small groups. • Report out on: – Anticipated challenges and possible solutions. – Support needed. – Other insights gained via process. 99 Wrap-Up and Closing Remarks Stakeholder Feedback Survey Lydotta Taylor, Ed.D. Alliance Lead, REL Appalachia Connect with us! www.relappalachia.org @REL_Appalachia Lydotta Taylor lmtaylor@edvgroup.org 101 Cited and other relevant sources Appleton, J. J., Christenson, S. L., & Furlong, M. J. (2008). Student engagement with school: Critical conceptual and methodological issues of the construct. Psychology in the Schools, 45, 369–386. Appleton, J. J., Christenson, S. L., Kim, D., & Reschly, A. L. (2006). Measuring cognitive and psychological engagement: Validation of the Student Engagement Instrument. Journal of School Psychology, 44, 427–445. Carter, M., McGee, R., Taylor, B., & Williams, S. (2007). Health outcomes in adolescence: Associations with family, friends, and school engagement. Journal of Adolescence, 30, 51–62. Christenson, S.L., Sinclair, M.F., Lehr, C.A., & Godber, Y. (2001). Promoting successful school completion: Critical conceptual and methodological guidelines. School Psychology Quarterly, 16, 468484. 102 Cited and other relevant sources (cont’d) Christenson, S. L., Sinclair, M. F., Lehr, C. A., & Hurley, C. M. (2000). Promoting successful school completion. In K. M. Minke & G. C. Bear (Eds.), Preventing school problems — Promoting school success: Strategies and programs that work (pp. 211-257). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists. Christenson, S.L. (2008, January 22). Engaging students with school: The essential dimensions of dropout prevention programs. [Webinar]. National Dropout Prevention Center for Students with Disabilities. Christenson, S. L., Reschly, A. L., Appleton, J. J., Berman, S., Spangers, D., & Varro, P. (2008). Best practices in fostering student engagement. In A. Thomas & J. Grimes (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology V (pp. 1099–1120). Washington, DC: National Association of School Psychologists. Christenson, S. L., Reschly, A. L., & Wylie, C. (Eds.). (2012). Handbook of Research on Student Engagement. New York: Springer. 103 Cited and other relevant sources (cont’d) Christenson, S. L., & Thurlow, M. L. (2004). Keeping kids in school: Efficacy of Check & Connect for dropout prevention. NASP Communiqué, 32(6), 37–40. Dynarski, M., & Gleason, P. (2002). How can we help? What we have learned from federal dropout prevention programs. Journal of Education for Students Placed At Risk, 7(1), 43-69. Finn, J. D. (1989). Withdrawing from school. Review of Educational Research, 59, 117–142. Finn, J. D. (1993). School engagement and students at risk. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. Finn, J.D. & Zimmer, K. (2012). Student engagement: What is it? Why does it matter? In S.L. Christenson, A.L. Reschly & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 97-131). New York: Springer. 104 Cited and other relevant sources (cont’d) Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. Fredricks, J., McColskey, W., Meli, J., Mordica, J., Montrosse, B., & Mooney, K. (2011). Measuring student engagement in upper elementary through high school: A description of 21 instruments (Issues & Answers Report, REL 2011–No. 098). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory Southeast. Retrieved September 13, 2013, from http://ies.ed.gove/ncee/edlabs. Gettinger, M. & Walther, M. J. (2012). Classroom strategies to enhance academic engaged time. In S.L. Christenson, A.L. Reschly & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 653-674). New York: Springer. 105 Cited and other relevant sources (cont’d) Jimerson, S., Campos, E., & Grief, J. (2003). Toward an understanding of definitions and measures of school engagement and related terms. The California School Psychologist, 8, 7–27. Jimerson, S., Renshaw, T., Stewart, K., Hart, S., & O’Malley, M. (2009). Promoting school completion through understanding school failure: A multi-factorial model of dropping out as a developmental process. Romanian Journal of School Psychology, 2, 12–29. Lee, V.E., & Smith, J.B. (1993). Effects of school restructuring on the achievement and engagement of middle-grade students. Sociology of Education, 66, 164-187. Lee, V. & Smith, J. (1999). Social support and achievement for young adolescents in Chicago: The role of school academic press. American Educational Research Journal, 36, 907–945. 106 Cited and other relevant sources (cont’d) McNeely, C. A., Nonnemaker, J. M., & Blum, R. W. (2002). Promoting school connectedness: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Journal of School Health, 72, 138–146. Mosher, R., & MacGowan, B. (1985). Assessing student engagement in secondary schools: Alternative conceptions, strategies of assessing, and instruments. A Resource Paper for The University of Wisconsin Research and Development Center. http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED272812 National Research Council and the Institute of Medicine. (2004). Engaging schools: Fostering high school students’ motivation to learn. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Newmann, F., Wehlage, G., & Lamborn, S. (1992). The significance and sources of student engagement. In F.M. Newmann (Ed.), Student engagement and achievement in American secondary schools. New York: Teachers College Press. 107 Cited and other relevant sources (cont’d) Patton, G. C., et al. (2006). Promoting social inclusion in schools: A grouprandomized trial of effects on student health risk behavior and wellbeing. American Journal of Public Health, 96, 1582–1587. Prevatt, F., & Kelly, F. D. (2003). Dropping out of school: A review of intervention programs. Journal of School Psychology, 41, 377-395. Reschly, A.L., Appleton, J.J., & Pohl, A. (2014). Best practices in fostering student engagement. In A. Thomas and P. Harrison (Eds.) Best practices in school psychology – 6th Ed. Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists. Reschly, A.L., & Christenson, S.L. (2012). Jingle, jangle, and conceptual haziness: Evolution and future directions of the engagement construct. In S.L. Christenson, A.L. Reschly & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 3-20). New York: Springer. 108 Cited and other Relevant Sources (cont’d) Shernoff, D., & Schmidt, J. (2008). Further evidence of an engagementachievement paradox among U.S. high school students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(5), 564–580. Skinner, E. A., Kindermann, T. A., & Furrer, C. J. (2009). A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection: Conceptualization and assessment of children’s behavioral and emotional participation in academic activities in the classroom. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 69(3), 493–525. Stout, K. E., & Christenson, S. L. (2009). Staying on track for high school graduation: Promoting student engagement. The Prevention Researcher, 16(3), 17–20. 109