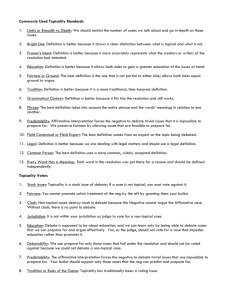

Topicality - Dartmouth 2012 - Voss

advertisement