A game plan for success, today and for the long term By Darryl

advertisement

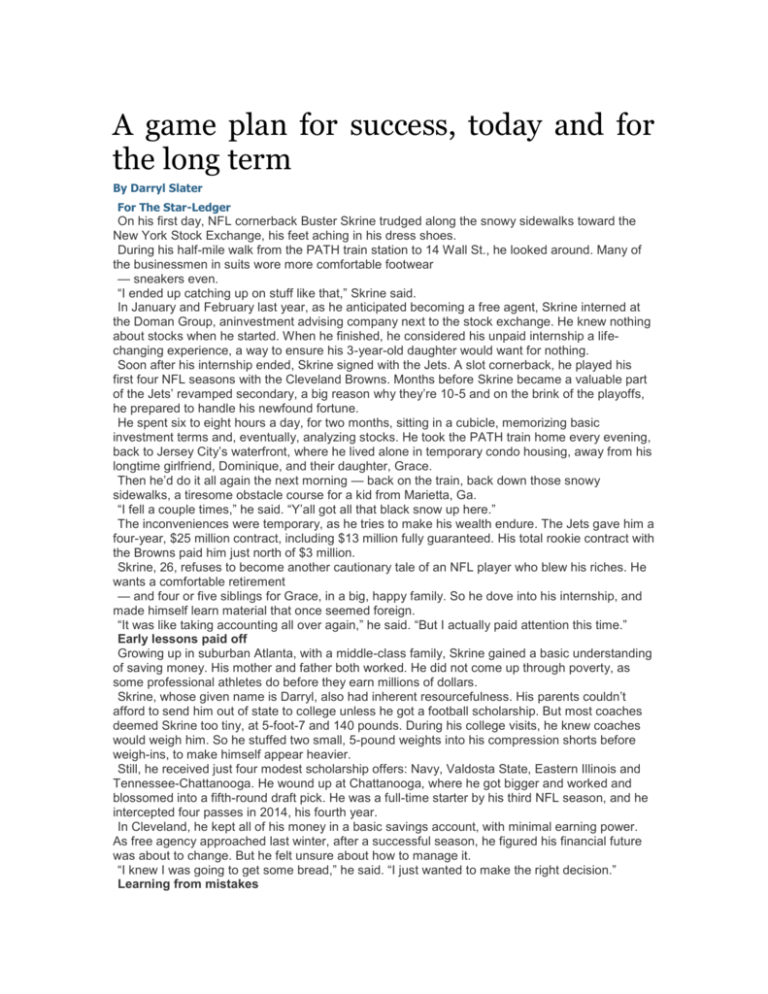

A game plan for success, today and for the long term By Darryl Slater For The Star-Ledger On his first day, NFL cornerback Buster Skrine trudged along the snowy sidewalks toward the New York Stock Exchange, his feet aching in his dress shoes. During his half-mile walk from the PATH train station to 14 Wall St., he looked around. Many of the businessmen in suits wore more comfortable footwear — sneakers even. “I ended up catching up on stuff like that,” Skrine said. In January and February last year, as he anticipated becoming a free agent, Skrine interned at the Doman Group, aninvestment advising company next to the stock exchange. He knew nothing about stocks when he started. When he finished, he considered his unpaid internship a lifechanging experience, a way to ensure his 3-year-old daughter would want for nothing. Soon after his internship ended, Skrine signed with the Jets. A slot cornerback, he played his first four NFL seasons with the Cleveland Browns. Months before Skrine became a valuable part of the Jets’ revamped secondary, a big reason why they’re 10-5 and on the brink of the playoffs, he prepared to handle his newfound fortune. He spent six to eight hours a day, for two months, sitting in a cubicle, memorizing basic investment terms and, eventually, analyzing stocks. He took the PATH train home every evening, back to Jersey City’s waterfront, where he lived alone in temporary condo housing, away from his longtime girlfriend, Dominique, and their daughter, Grace. Then he’d do it all again the next morning — back on the train, back down those snowy sidewalks, a tiresome obstacle course for a kid from Marietta, Ga. “I fell a couple times,” he said. “Y’all got all that black snow up here.” The inconveniences were temporary, as he tries to make his wealth endure. The Jets gave him a four-year, $25 million contract, including $13 million fully guaranteed. His total rookie contract with the Browns paid him just north of $3 million. Skrine, 26, refuses to become another cautionary tale of an NFL player who blew his riches. He wants a comfortable retirement — and four or five siblings for Grace, in a big, happy family. So he dove into his internship, and made himself learn material that once seemed foreign. “It was like taking accounting all over again,” he said. “But I actually paid attention this time.” Early lessons paid off Growing up in suburban Atlanta, with a middle-class family, Skrine gained a basic understanding of saving money. His mother and father both worked. He did not come up through poverty, as some professional athletes do before they earn millions of dollars. Skrine, whose given name is Darryl, also had inherent resourcefulness. His parents couldn’t afford to send him out of state to college unless he got a football scholarship. But most coaches deemed Skrine too tiny, at 5-foot-7 and 140 pounds. During his college visits, he knew coaches would weigh him. So he stuffed two small, 5-pound weights into his compression shorts before weigh-ins, to make himself appear heavier. Still, he received just four modest scholarship offers: Navy, Valdosta State, Eastern Illinois and Tennessee-Chattanooga. He wound up at Chattanooga, where he got bigger and worked and blossomed into a fifth-round draft pick. He was a full-time starter by his third NFL season, and he intercepted four passes in 2014, his fourth year. In Cleveland, he kept all of his money in a basic savings account, with minimal earning power. As free agency approached last winter, after a successful season, he figured his financial future was about to change. But he felt unsure about how to manage it. “I knew I was going to get some bread,” he said. “I just wanted to make the right decision.” Learning from mistakes Years ago, before he ran his own Wall Street investment firm, Mark Doman interned at the NFL Players Association. He encountered far too many cases of former players who couldn’t support themselves after burning through their millions. This troubled Doman, and he wanted to change pro athletes’ financial goals from short-term, fleeting fun to long-term security. The Doman Group manages money for about 30 current NFL players, in addition to its other wealthy clients. Skrine’s agent, Jared Fox, and a Browns teammate, defensive end Desmond Bryant, suggested Skrine contact Doman while looking for a financial adviser. Bryant is also one of eight pro athlete clients who interned at Doman’s office. Former Knicks player Landry Fields is another. This offseason, NFL players Devon Still and NaVorro Bowman will do the internship. When Doman offered Skrine the chance to intern, Skrine jumped at it. He wanted to see how Doman operated before handing over a lot of his money. But Doman’s internships are about more than watching. He makes the athletes learn. Skrine stood out in Doman’s office, where other interns are MBA students from Columbia and NYU. Skrine wears his hair in short, gold-dyed dreadlocks, pulled up into a sprout, with his head shaved on the sides and back. He likes his style, so he kept his earrings in, while wearing dress clothes every day, but not a full suit. “Only one in the building that looked like that,” he said with a smile. What actually mattered is if he could act the part. Skrine majored in business management at Chattanooga. He is 14 credits shy of his degree, which he plans to earn. With Doman, Skrine started by learning investment vocabulary — stock, trade, dividend. He then had to analyze the initial stocks and bonds portfolio he set up with Doman — mostly bigname, large-cap stocks along the lines of Google and McDonald’s. Skrine’s task: Give Doman a synopsis of every stock in his portfolio, and compare it to data for similar, competitive stocks. Which stocks are conservative? Which are aggressive? Skrine’s final assignment was a presentation to Doman’s investment committee, a group of stock analysts and portfolio managers. Skrine had to explain to the committee why he thought the company picked particular stocks, whether they were sensible choices, or if an alternative stock might be wiser. “He knocked it out of the park,” Doman said of Skrine’s presentation. “Once we got him to realize (during the internship) that what we do is not rocket science, but in fact just involves a lot of diligence, he became very confident in using instincts to give his opinion.” Budgeting for the future Skrine wouldn’t budge on the blue Lamborghini. The internship couldn’t change his mind about that. Not that Doman didn’t try. His biggest message to Skrine, during those two months, involved the value of long-term, stable investment over short-term splurging, or pouring money into flashier investment opportunities. “To get him to understand that although it’s not quite as sexy as investing in, say, a restaurant, the goal here is to preserve the capital and make it appreciate over a longer period of time,” Doman said. “That was a real challenge, trying to get him to understand that it’s not simply about how sexy the opportunity is. It’s more about what the opportunities mean for the long term.” But Skrine’s mind was set on that Lamborghini. He loves cars, just like he loves fashionable clothes and shoes. He owns a used car dealership with his dad and brother back in Atlanta. Skrine vowed to treat himself with the Lamborghini when he landed his first big contract, even though he said Doman insisted against it. “He didn’t have no shot at that one,” Skrine said. “Zero.” Almost all of Doman’s lessons did stick with Skrine, as he maps out his promising future. Near the end of Skrine’s internship, as free agency approached and Skrine wasn’t sure where he’d wind up, he walked into Doman’s office. “I wanted you to know that you’ve literally changed my life,” Skrine told Doman. Doman, touched by the gesture, thanked Skrine for trusting him with his money. “But it’s better that you understand how we manage it,” Doman replied. Now, in the Jets’ locker room, Skrine raves about stocks he chose for his own portfolio: Eagle Eye Networks (a security camera company), Apple and Tesla, the electric car company whose in- development, super high-speed train between Los Angeles and San Francisco intrigues Skrine, for its stock-growth potential. “The biggest thing I probably took (from the internship) is there’s a difference between being rich and being wealthy,” Skrine said. “A lot of NFL players, they spend, spend. And they’re done (playing), and they want to spend the same way, but you can’t. “After I’m playing, I know I’m not going to spend the exact same way, but I want to be able to spend close. I feel like I’m on the right track right now. Just knowing how to save and ways to make more money with your money, and coming up with a plan, which a lot of people don’t have. That helped me see my future and the path I wanted to go on.” Darryl Slater, NJ Advance Media, dslater@njadvance media.com