Limited growth: Japanese Challenge? Global crisis? VASZKUN

advertisement

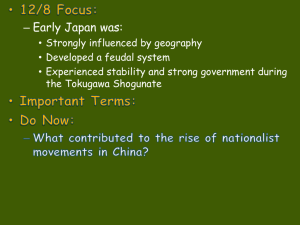

KORLÁTOS NÖVEKEDÉS: JAPÁN DILEMMA? GLOBÁLIS VÁLSÁG? LIMITED GROWTH: JAPANESE CHALLENGE? GLOBAL CRISIS? VASZKUN Balázs Budapesti Corvinus Egyetem, Gazdálkodástudományi Kar, H-1093 Budapest, Fővám tér 8. e-mail: balazs.vaszkun@uni-corvinus.hu Giving up biodiversity and natural resources gives to mankind the illusion of sustainable growth. We all know that nothing can be unlimited but Japan is a good example in offering further understanding on growth. Our boundaries may help us humans to find balance again before it gets too late. Natural resources and agriculture are the basis for industry and our nutrition; but water, land, minerals, food may also one day put on end to further development. Japan being almost symbol of restricted access to industrial inputs learned the challenge of this situation, enjoyed the high-speed growth but faced also the sudden halt. The inputs of rising seemed to be at end: the increasing population, export markets and prices. But more than Japan only, the whole industrial world is now learning a lesson on the price of pushed growth and its effects are important to observe and analyze. Stronger regulation and self-protecting countries might play a role in a going-back-process. When export can’t grow, import must be controlled also in order to keep healthy payment balance which will put focus on domestic production, even if less productive or efficient. In this paper we attempted to have a mirror to this theory by a survey conducted in Japan on recent attitude of people about old business practices. We interpreted responses using this theoretical perspective of limited growth and stated that crises help us humans to understand our boundaries. In a sense, this logic ensures survival of some diversity which seems to get supported naturally in a cyclical manner. Introduction Japan is known today as one of the most environment- and resource-conscious among industrialized countries. Overconsumption hardly exists, and the population is using resources in an extremely careful, conscious way. Common wisdom explains that phenomenon by the island-effect and their limited resources. Japanese are more into savings than in consumption which is proportionally very low as a consequence. This is one of the main causes of recent deflation. More than just of natural resources, Japan is limited by the lack of land: on a territory of approximately the size of Hungary are living about 127 million people today. No wonder, that Japanese are familiar with the term of ‘limited growth’. Thus, the Western world, giving up biodiversity and natural resources, is talking about ‘sustainable growth’. This difference might be worth to be observed more in details. As we know, Japan used to be formally a feudalistic society until the Meiji era. Informally, traditional customs and rules remained in practice even after 1868. This means, that the basis of life used to be the agriculture for much longer time than in Europe, where industrialization started in the 18th century. Over 80% of the population being directly linked to the nature in their everyday life, their earnings depended also much on the weather and natural resources (Totman, 2006). That meant limited wealth for few, general poverty for the rest – especially during the three main famines of the Edo-era. Victim of that poverty, the society vividly remembered the starving masses even generations later and forbade every member to waste food or any kind of resources. These were also often subject of violent disputes between villages or individuals (Satō, 1990). Even in the industrialized era, the tragic memory of the lost world war and the harsh living conditions following the defeat reinforced in people’s mind the material value of products. Also, it is interesting to mention the role of the saving campaigns of the government (Garon, 1997). The financial than global crisis of 2008 and 2009 brought a good prove that growth, especially high growth can be but limited. It has been preceded by the Nippon bubble burst in 1990 which also put an end to a growth period. What is new for the US or Europe, is twenty years old in Japan which makes this example especially interesting and relevant. What kind of reactions can we give to crisis and stopped growth? How to find balance between growth and sustainability? Looking at Japan might lead us to further understanding. Crises in the Edo-period The bubble burst is not the first crisis in Japan stopping growth. In order to identify different milestones, it is worth to take a look on the demographic evolution. Figure 1: Demographic evolution in Japan from the year 700 (million people) 140.0 120.0 100.0 80.0 60.0 40.0 20.0 0.0 700 900 1200 1600 1700 1721 1780 1846 1872 1890 1915 1920 1940 1960 1980 1990 2000 2010* * Estimated data Source: Japan Statistics Bureau and Statistics Center; Totman (2006); compiled by the author The shape of the curve here is slightly biased, due to the imbalances within the timeline, but it does still well reflect the two main breakpoints in history which were obviously harmful to the population. The first one occurred during the 1710s, after which masses must have died, and the other happened in the 1970s which ended the almost exponential growth of the postwar population. In the 1710s, Japan was under the rule of the Tokugawa dynasty, the shogun (military chief) holding the effective power to command above the emperor. In order to better understand what happened in the 1710s, we must take a short look to the starting point of the curve in the 1600s. In 1603, Tokugawa Ieyasu became supreme military leader (entitled shogun) of the freshly united Japan, after centuries of constant war between the feudal lords. In a recent term, we might say that the era of the Warring States has been the period of perfect competition, promoting innovation and meritocracy. But at that time, it brought miserable poverty, hopeless struggling for survival and ever increasing taxes for the commoners. From to war period to the peace under Tokugawa, the tax on the peasants went down from 70 to 30%!1 Also, the unification of the country and the long-lasting peace opened the way among others to much agricultural and economic development resulting in increasing population. Enhanced irrigation systems and river regulation, increasing size of the rice fields, easier and cheaper transportation… As Tokugawa (2009) emphasizes the achievement: “within a century (once the Tokugawa peace installed), rice output increased 2.5 times.” (p.72) Wealth in the Edo-era was measured by the quantity of rice produced by the village or domain and that became also the basis of the power of landlords (daimyo). In years of bad harvest, the whole nation suffered. The increase in the population had been stopped first by the famine of the 1710s when the size of the country reached a limit in regard to the natural resources as wood, land, food, or water. (Totman, 2006) By that time, Edo, the capital became the largest city in the world with a population of 1,000,000. The food produced by the irrigation and fertilization technology of the time was simply not enough for a further growing society. The rice tax was increasing but landlords could make less use of it as the relative price of the appearing industrial products like cotton got always higher. (Nakamura, 1990) Also, the production of timber and excessive use of forests while extracting green fertilizers resulted in serious shortcoming in woods. Villagers became hostile to any foreigner as there were no more space for new houses and rice fields. But in comparison, at that time as in 1853 (first official meeting between the US and Japan), Western societies still had no idea about limited growth. (Tokugawa, 2009) In 1716 came into power an important personage of the Edo-period: Tokugawa Yoshimune, who made it possible even for lower-ranked samurai to rise in higher bureaucratic positions and so made the system more meritocratic. Increasing the quality of the ruling bureaucrats, he also played an important role promoting modest lifestyle even among the high-class society and the richest merchant houses. He became one of the symbolic personages of the Japanese culture afterwards, emphasizing self-control, respect, modesty, and economic consciousness. He introduced costless customs as writing haiku poems, watching flowers (hanami), or eating ‘fast-food’ (like tempura, soba, sushi) and keep working hard all day long.2 Extravagant lifestyle has been punished, and entire merchant houses vanished suffering the disgrace of the shogun. (Sakudō, 1990) 1 The fact has been highlighted by Tokugawa Tsunenari during his lecture in the International House of Japan, on the 9 June, 2010 2 Idem With severe self-control only could the Japanese society survive the returning famines (1780s, 1830s) of the feudal era. As Tokugawa Tsunenari describes in 2009: Edo society was a society that wasted nothing. Even human waste was fully utilized as a valuable organic fertilizer. Paper was recycled; wooden utensils and tools were used until they could be used no more and then burned for fuel. Kimonos were worn until threadbare, than used to make futons. Ash from cookstoves was collected for a variety of uses; hair was gathered from beauty parlor floors to make wigs or hair extensions. The tiny amount of wax left by burnt candles was collected to make new ones. (p.142) The proportion of recycled materials remained high until today in Japan. Postwar growth and crisis We can use that example from feudalism as a parallel to the postwar growth and sudden halt. As shown by Figure 1, high growth in population begun in the 1930s with the massive industrialization and the strengthening national identity and lasted until the 1980s. A zoom on the ‘40s would show a fall at the end of the war but proportionally to the size of the society, human losses were not as important as caused by medieval famine. What factors have been supporting that new growth era? Ways of mass-production became more and more accessible in Japan, which ensured industrial goods and more food for a hitherto agricultural economy. The agriculture also remained important. Increasing population is for sure a good basis for general development, until they can enter the employment system from the labor market. Japan being still a relatively small country, especially in terms of rentability of mass-production systems, the most powerful factor could be the growing export markets, as Japanese labor was definitely cheaper than other industrialized nations. (Hirschmeier and Yui, 1981; Weinstein, 2001) However, with the high growth, the cost of labor also started to rise. This, together with the ‘voluntary export restrictions’ requested by the US and the rising energy prices after the Oil Shock, seemed to refrain much the export industries. (Hirschmeier and Yui, 1981; Dore, 2000; Pyle, 1996) With companies losing their markets, the education cannot guarantee employment anymore which results in a crisis at the school and in the families. Did Japan reach her growth limits in the ‘80s? More than shrinking jobs or markets, a morning in the crowded metro would suggest to probably any reader a definite ‘Yes’ – meaning also another constraint in terms of density of the population. Tokyo, with Yokohama and the metropolitan area, remains the largest metropolis in the world. Now the population is not only decreasing but aging seriously, transforming the overall needs and capacities of the society. Younger people have no or very limited access to wealth accumulation as the proportion of regular (better paid) jobs is in permanent decrease since the ‘90s. The whole Japanese economy and management system has been designed during the postwar years based on the high growth. People apparently had the illusion that it would last forever. The so-called ‘lifetime employment’ which institutionalized in the 1920s, became common practice – especially in larger companies. (Nakane, 1972) This practice supposes no strong downturns in the operations, except with significant non-regulars being used as ‘puffer’. Also, the famous long-term vision of the Japanese managers would have been more difficult in a hectic environment. The seniority based wages and promotions ensure constantly rising allowances for the employees which is obviously difficult without growth. The same goes for the enterprise unions whose main activity became the annual negotiation for wage increase concerning the totality of the regular workers. (Dore 1973; Ouchi 1981; Kono and Clegg 2001) Japan, her export markets taken as granted, could also afford to protect her own industries and markets from excessive import and FDI. But now, twenty years after the bubble burst and the beginning of the ‘lost decade’, the situation seems to change radically – at least concerning economic growth and its image in people’s mind. Three hundred years ago, in the Edo-period, solution to the crisis has been enhanced selfcontrol, recycling, elimination of waste and extravagant customs. In today’s Japan, low consumption seems to be rather problematic as it does hold back production and refrain the economy from growing again. But how could growth be provided with a shrinking population and in an ever intensifying global competition on prices, where quantity wins with large-scale production? We can assume that in order to keep domestic markets from cheaper imports, countries must either produce at an even larger scale (the way of growth), ‘hypnotize’ their citizens to buy only domestic products (no democratic way) or protect their own markets by other means concerning trade. It seems to be time to reconsider the whole idea of growth and think about whether it is really a necessity for a decent life. In this new crisis, the traditional economic and management model does certainly need adaptations. Common wisdom suggests that in a democratic regime, best answers come from the citizens much more than from just a handful of political leaders. In the last part of this paper, we are going to examine how residents in Japan think about growth or traditional business practices, what are their attitudes towards the old and what would be the new if change does happen. We use here Japanese management as a symbol or metaphor for growth crisis and assume that findings on management can be served as example for general attitudes on crisis. Research hypothesis Continuing the logic of the previous chapters, the first assumption must concern the general mindset of the Japanese: our hypothesis would be that they are fully aware and conscious of that growth cannot be sustained forever. In terms of management, here is an example: The majority of the Japanese society admits that seniority wages and promotions cannot be sustained as dominant motivators. We have had six questions related to growth. According to this hypothesis, each of those questions must have responses reflecting a good level of consciousness of limits. Also, as a consequence of their traditions and economic past, as well as the growth crisis, we must think that many Japanese would tend to protect domestic market from free competition. Those persons gave a favorable rating for the following statement: It is important to protect our markets and jobs from foreign competition. This idea is not new but today has a different meaning: in the 1960s it supported growth, today it would aim survival. Probably the ones who accept free competition in general are more confident in their capabilities and tend to be against traditional collectivist ways managing business and the economy (as those ways tend to favor average against outstanding). We have had six questions in order to monitor support or aversion towards traditional ‘Japanese-style’ management. Research Methodology The research is based on a questionnaire survey conducted in Tokyo, Japan, from April 2010 to July 2010. The panel has been collected via internet based questionnaire using snowball sampling, the main criteria being ‘resident status’ in Japan. Our analysis is based on the answers of 182 respondents, Japanese or Foreigner. We can find a good balance in gender as less than 54% of the respondents are male and more than 46% female. 47% of the total panel is Japanese and all together 67.5% are from Asia. The education level is generally good: 57% graduated from college (4 year long superior education) and 40% did a master or PhD. More than 60% did already work in Japan. The status and age proportions are represented by Figures 1. and 2. Figure 1: Status Figure 2: Age groups Status manager 9% reg 28% 604% 46-59 11% Age 19-25 35% student 49% 26-45 50% non-reg 14% Table 1 shows the questions we asked with the global average response and the variance. Data will be further developed in the next chapter, though. In the questionnaire two types of question had been answered: yes or no questions (the first three in Table 1.) and seven-scale questions. The second, usually based on “How much do you agree…” sentences, offered seven options for respondents: strongly agree (coded as 7), mostly agree (6), slightly agree (5), neutral (4), slightly disagree (3), mostly disagree (2), and strongly disagree (1). The first six questions are (based on the logic above) directly related to growth. It is good to remember that the first three questions (or sentences) contains ‘yes’ answers, coded as ‘1’; and ‘no’ answers, coded as ‘0’. The other items have been rated between ‘7’ and ‘1’. The last six questions monitor attitudes towards traditional Japanese management. The item containing ‘Lifetime employment is outdated…’ is a control question surveying personal attitudes. The number of questions and the size of the sample made it possible to overview and analyze data without very sophisticated statistical methods. In order to keep the following chapter easy to understand, only basic calculations have been used as averages, variances, sum and so on. Table 1. Questions, averages and variances AV VAR It is OK to fall in promotion behind colleagues recruited in the same time as you Item 0,6 0,24 Would you accept in crisis situation reduced wage / work time in order to keep general job safety? 0,9 0,12 A company should guarantee for its best workers lifelong employment 0,4 0,25 The best way to increase size for a company is to hire more young graduates from top universities 3,1 1,98 Employees recruited in the same time should basically be promoted together: it fosters cooperation between members, limiting harmful competition 2,8 2,01 I would rather work for a large organization than a small one 4,2 2,57 Lifetime (or long-term) employment is outdated: I don’t want to stay in the same company for so long time 4,3 2,95 It is important to protect our markets and jobs from foreign competition 4,0 2,69 Salaries should be entirely based on performance, no matter the age or seniority of employees 4,9 2,54 If a person is highly qualified he/she should be quickly promoted even if his/her subordinates end up being much older than he/she is 5,7 1,35 Japan should move more towards the American economy and its institutions, changing its old, outdated practices 3,7 2,35 Japan should find its own way to recover from crises, based on its traditions and culture 5,1 1,99 The key success factor for a company is to produce good quality products at an affordable price – succeeding in this ensures almost automatic success 3,9 2,43 Japanese companies should pay more attention to efficient marketing: today it may be more important than the quality of the products 4,7 2,22 Findings and rationale In the first hypothesis, we predicted already some reactions concerning growth. It is OK to fall in promotion behind colleagues recruited in the same time as you. 63% ‘voted’ with ‘yes’ which is certainly a majority. 63% of the sample recognized that it is not possible or maybe not good to promote everybody in the same time along a seniority scale and accepted this fact for him- or herself. No wonder, that looking at younger generations the result is weaker: only 54% of the respondents below age 26 marked ‘yes’ here (against 86% with people over 60 or 76% by regular workers. Would you accept in crisis situation reduced wage / work time in order to keep general job safety? Here the overall average is an overwhelming 86% which is topped at the age of 46-59 with 95% ‘yes’ answers. Not only growth cannot last forever but respondents here do accept downturns as well, where individual earnings may be sacrificed for public interest. A company should guarantee for its best workers lifelong employment. This sentence refers to a traditional element of the Japanese employment system which is hardly sustainable in a steadily decreasing economy. A minority, 43% think that it is still an affordable privilege for rewarding the bests. It is even less with females (39%, but they have been usually excluded from that advantage) or young people below age 26 (38%). Negative record is reached by respondents originated from Anglo-Saxon countries (US, Britain, Australia, Canada) with only 33% ‘yes’. Thus, this item has a relative low variance. The best way to increase size for a company is to hire more young graduates from top universities Recruiting directly from schools is still a current way in Japan today although it is highly criticized for blocking mid-career options. For long time, seniority wages have been balanced with the lower paid new graduates but in the last two decades companies could not afford recruiting as much as to reach this balance effect. (Abegglen, 2006) Today’s society may agree with these critics as in that sample the average score is 3 to that sentence, meaning a slight disagreement. No wonder that disagreement is rising with age and reaches already a score 2.0 with people older than 60. Also, Anglo-Saxons scored it very low (2.56) as their job markets are dominated by recruitment agencies offering wide-range mid-career opportunities. Employees recruited in the same time should basically be promoted together: it fosters cooperation between members, limiting harmful competition This is a control question to the first one with a wider range of answer possible. As pure logic would have been suggested, this sentence got little support: the average answer being 2.79 which is between disagreeing ‘slightly’ and ‘mostly’. Here again, the Japanese (with 2.67) are apparently overwriting their old customs according to the new conditions. I would rather work for a large organization than a small one Positive attitude towards large companies rather than towards smaller ones does certainly motivate further increase in firm size and turnover. Small size companies can hardly follow bigger ones relative to the package offered to young recruits including promotion prospects and non-monetary benefits. For that reason, it is hardly possible that opinion to that sentence would turn into negative. Today in Japan, the score seems to be approaching to the neutrality (4.23) which is quite amazing given the classically huge difference between small and big size firms. To make a short sum up, the majority of the respondents seems to be conscious about limitations and do not dream about unrealistic advantages directly related to constant growth. Now let’s turn to the question whether this awareness is turning into protectionism in business. It is important to protect our markets and jobs from foreign competition With an average of 4.04 (4 means neutral, no agreement but no disagreement), respondents seem to have lost interest in closing borders from trade and foreign influences or pressures. However, two points seem worth to be made: One is a tendency according to age: average older people would still support the idea of protection (4.71). This score is decreasing: 4.43 between ages 46 and 59; 3.7 between 26 and 45 (which turns into disagreement) but jumps up again below age 26 to 4.32! We can conclude that dominant groups in today’s society are not tempted any more by protecting and closing the country again – at least based on this sample. In the same time, from fear of losing job options, or by the melancholy of sad family stories, the future’s generation seems to be less motivated by competition does not want to ‘fight’. An important note here is the difference between Japanese (4.57) and Anglo-Saxon residents (3.74), which still shows some Japanese tendency to regulate instead of compete. In order to evaluate our third hypothesis, in the next paragraph we consider separately those who rated the previous item as ‘1’, ‘2’, or ‘3’ (showing disagreement). They are 69, well educated (with at least a master degree), and somewhat dominated by males (61%). There is at least one item with remarkable distance between this subgroup and the overall average: The key success factor for a company is to produce good quality products at an affordable price – succeeding in this ensures almost automatic success. About this image of competition, our subgroup tends to disagree much stronger than the rest of the sample: their average score being 3.49 compared to the 3.91 in total. Actually they had the lowest score here among every other subgroups based on age, company, etc. This is interesting enough to stop here a little. During the second half of the 20th century, Japan’s strength has been her production system which manufactured cheap and good quality (after several quality improvement program) products. One reason for the bubble crisis is probably the fact that the economy arrived to a development where manufacturing has to give space to services: the labor cost got already too high compared to later industrializing countries. This sentence claims the validity of the past era, based on manufacturing. Disagreement by contrast approves the necessity on passing to more sophisticated marketing or other means, through which Japan can avoid price competition mentioned by Porter, Takeuchi and Sakakibara (2000) or Schaede (2008). Conclusion Seeking growth is human which made it also the basis of capitalism. In this paper we did not argue for - or expect growth-seeking to disappear; but we concluded that growth, as many times in history, sometime stops. As mankind is looking for it and expecting it, that is why crisis occurs. In historical Japan, the answer given to recession had been increasing self-control and waste-reduction. Some authors put forward this attitude even in the 21st century, when it could be remedy for some problems but poison for others like deflation. Japan being a country with long experience accumulated on limited growth must serve as example in dealing with the recent global crises. Research experience shows that citizens in Japan are fully aware, maybe more aware than in any other industrialized country, of the dangers of limited resources and had developed a sense of crisis related to growth limits. Also, there is a part in the Japanese population which is fully competitive and also willing to prove it. They are leaving behind traditions and customs too strongly linked to the rising economy. In the same time, they are keeping memories on poverty and severe restrictions from Japan’s past. Among different nations, the difference is made by how do they perceive lack of growth, how do they react on it and whether they consider it as an option or not. As Japan did, we must accept our limits while not forgetting our goals. But as to put a definite end to the crisis, Japan as other countries as well, seems having a long way to go. Bibliography Abegglen, J. C. (2006). 21st-Century Japanese Management: New Systems, Lasting Values. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. Abegglen, J. C. (1960). The Japanese Factory: Aspects of its Social Organization. Glencoe, Illinois: The Free Press. Dore, R. (1973). British Factory – Japanese Factory: The Origins of National Diversity in Industrial Relations. London: George Allen & Unwin. Dore, R. (2000). Stock Market Capitalism: Welfare Capitalism. Japan and Germany versus the Anglo-Saxons. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Garon, S. (1997). Molding Japanese Minds: The State in Everyday Life. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. Hirschmeier, J., & Yui, T. (1981). The Development of Japanese Business: 1600-1980. London: George Allen & Unwin. Ioku, S. (2007). Local Markets and the Development of Agriculture and the Agriculture Processing Industry in the 19th Century Japan. In B. H. Japan, Japanese Research in Business History (pp. 77-96). Tokyo: Business History Society of Japan. Kono, T., & Clegg, S. (2001). Trends in Japanese Management: Continuing Strengths, Current Problems and Changing Priorities. New York: Palgrave. Marosi, M. (2003). Japán, koreai és kínai menedzsment. Budapest: Aula. Nakamura, S. (1990). The development of rural industry. In C. Nakane, & S. Oishi, Tokugawa Japan: The Social and Economic Antecedents of Modern Japan (pp. 81-95). Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press. Nakane, C. ed. (1972). Japanese Society. Berkeley: University of California Press. Nakane, C., & Oishi, S. (1990). Tokugawa Japan: The Social and Economic Antecedents of Modern Japan. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press. Ouchi, W. G. (1981). Theory Z : how American business can meet the Japanese challenge. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley. Porter, M. E., Takeuchi, H., & Sakakibara, M. (2000). Can Japan Compete? Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan. Pyle, K. B. (1996). The Making of Modern Japan. Lexington, Mass: D.C. Heath. Sakudō, Y. (1990). The management practices of family business. In C. Nakane, & S. Oishi, Tokugawa Japan: The Social and Economic Antecedents of Modern Japan (old.: 147-166). Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press. Satō, T. (1990). Tokugawa villages and agriculture. In C. Nakane, & S. Oishi, Tokugawa Japan: The Social and Economic Antecedents of Modern Japan (old.: 37-80). Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press. Schaede, U. (2008). Choose and Focus: Japanese Business Strategies for the 21st Century. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. Thomann, B. (2008). Le salarié et l’entreprise dans le Japon contemporain: Formes, genèse et mutations d’une relation de dépendance (1868-1999). Paris: Les Indes savantes. Tokugawa, T. (2009). The Edo Inheritance. Tokyo: International House of Japan. Totman, C. (2006). Japán története. Budapest: Osiris. Weinstein, D. E. (2001). Historical, Structural, and Macroeconomic Perspectives on the Japanese Economic Crisis. In M. Blomström, B. Gangnes, & S. La Croix, Japan's New Economy: Continuity and Change in the Twenty-First Century (old.: 29-47). Oxford: Oxford University Press.