Research Design and the Logic of Control

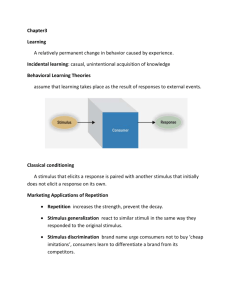

advertisement

During the 2010 congressional elections and even now, Republicans repeatedly asserted that the Bush/Obama fiscal stimulus did not work. Rather, it just built up trillions in federal debt that future generations would have to pay off. For example, our newly elected local congressman, Bill Flores, advertised then and recently said that joblessness increased by over seven million during the time the stimulus was occurring. What we need is to allow the private sector to work by getting government out of the economy. While these arguments undoubtedly paid political capital and may have sounded good to those inclined to vote for him, the science behind these arguments is problematic. Why? There was no control. In order to be able to conclude anything at all about the success of the stimulus, one would need to know what happened to a group which did NOT receive the stimulus. We need a both a treatment and a control in order to make causal explanations. Perhaps the stimulus did actually work, but that other factors were functioning simultaneously to make the economy worse. Thus, as scientists we need to ask: What would the economy have been like without the stimulus? For those who did not receive the stimulus (an imaginary group), what would have happened. This is the issue of control for rival explanations. The issue of control is fundamental to being able to make causal explanations. Politicians and people live in a much simpler world and are often willing to accept explanations offered by those they trust, especially if they coincide with one’s predispositions. However, as scientists it is our obligation to flesh out the truth whenever it is possible to do so, regardless of its implications for our political views. The political world is a very complicated place. For every explanation there are often competing explanations. Our job is to determine which of the competing explanations is true. In the case of the Bush/Obama economic stimulus it will probably not be possible to flesh out the truth. Why? There was no control group which did not receive the stimulus. It was applied uniformly to the entire nation. It would have been unethical to withhold the stimulus because of the economic implications for those who did not receive it. Similarly, there are often rival explanations for most things we want to explain. Consider our earlier discussion on concealed handguns on college campuses. We hypothesized that partisanship was probably a good explanation for supporting this initiative. However, there are other possible rival explanations which require “controlling for” if we are to be able to make causal statements. Gender might explain this phenomenon. Women are more likely to be Democrats and Men are more likely to be Republicans. Further, Women are generally stronger gun control advocates than men. These rival explanations undermine our ability to reach causal conclusions about how partisanship affects support for guns on campus. Is the independent variable, partisanship, causing support/non-support for guns on campus. Or, is some other variable at work such as gender, distorting our results and leading us to erroneous conclusions. Our ability to rule out competing explanations depends on the power of our research design. We can approach this problem by designing an experimental study. An experimental study typically contains a treatment group and a control group. The experimental subjects are similar in every way, except that the treatment group receives the stimulus and the control group does not. This isolation of only one group receiving the stimulus allows us to make causal explanations. We can also approach this problem by designing an observational study. Here the researcher makes controlled comparisons. That is, the researcher observes the effect of the independent variable of interest on the dependent variable, while holding constant all other plausible causes of the dependent variable. In all experiments, the investigator manipulates a treatment group and a control group in such a way that, in the beginning, the two groups are virtually identical in every way. Measurement is taken prior to the application of a stimulus. The two groups then receive different values of the independent variable of interest. Typically, the treatment group receives the stimulus, while the control group does not. Measurement is then taken of both groups after the application of the stimulus. Since the two groups are identical in every way, except in their receipt of the stimulus, any observed differences in the dependent variable cannot be attributed to rival explanations. In a laboratory experiment, the treatment group and control group are studied in an environment wholly created by the investigator. For example, we have an experimental lab in this building where students participate in experiments while sitting in front of a computer screen. Participants are generally aware that an experiment is taking place, but are often unaware of the purpose. In laboratory experiments subjects are recruited to a common location, the experiment is largely conducted at that location, and the researcher controls almost all aspects in the environment in that location except for subject behavior. In a field experiment, the treatment and control group are studied in their natural environment, living their lives normally, probably unaware that an experiment is taking place. In a field experiment the researcher’s intervention takes place in an environment where the researcher has only limited control beyond the intervention conducted. Both types of experiments generally depend on random assignment for control. Random assignment occurs when each prospective participant has an equal probability of being in the treatment and control groups. Suppose we want to study the effect of candidates’ racial attributes on people’s political behavior. For example, I have a colleague who studied the effect of racial attributes in Mexican election behavior. In Mexico there is a diversity of racial features among the population. There are people of Spanish origin who appear caucasian; there are people of Mulatto origin who are very dark; there are people of Indian origin whose features are less dark but have distinctly Mongol features. The treatment is showing participants pictures of three candidates. • One picture depicts Candidate A with obvious Spanish features. • A second picture depicts Candidate B who is very dark, probably mulatto (mix between caucasian and African). • A third picture shows Candidate C who has clear Indian features, probably descended from mixed caucasion/Mayan or Aztec populations. The participants are read identical candidate profiles for the three. Each is well-educated, has a legal background, and is very successful. Participants are randomly assigned to three groups. Each of the three groups is shown a different picture at the same time they see the candidate profiles. Participants in each group are then asked which candidate they prefer in the upcoming Mexican election to represent their district. A significant difference is observed between groups in preferences for the three candidates. The candidate who appears Spanish is preferred over the candidate who appears Indian, who is in turn preferred over the candidate who appears African. What can we conclude? Why? What is the role of “control” in allowing us to make these conclusions? In order to make conclusions we need good random assignment. In other words, the three groups need to be identical in every way. Random assignment is the great equalizer of rival explanations. Internal validity means that the experiment successfully controls for rival explanations that might cause the treatment response. External validity refers to whether or not the results from an experiment are “generalizable” to the population. Laboratory experiments generally have high internal validity, but low external validity. For example, the preceding experiment involved participants who knew they were participating in an experiment. How might this have affected the results? It is common for political scientists to use “college students” or “internet respondents” when conducting laboratory experiments. How might this affect the external validity of experiments? Field experiments are conducted in the real world and can sometimes overcome the limitations of laboratory experiments. Gerber, Karlan, and Bergen (2007) conducted a field experiment on how exposure to various media outlets affects voting behavior. They randomly selected households in Prince William County Virginia to receive treatments prior to the 2005 Virginia gubernatorial election.. Postcard to Subjects Congratulations! You have won a free Ten week subscription to The Washington Post/Washington Times! We have held a drawing to award free ten-week subscriptions of The Washington Post to households in Prince William County. Delivery begins this week. Delivery will automatically end after ten weeks, you do not need to call to cancel. However, if you want to cancel before the end of the ten weeks, please call 1-800-635-9224 and we will remove you from this promotion. Thank you for trying out the newspaper. Group A was selected to receive a free newspaper subscription to the Washington Post (a liberal media outlet). Group B was selected to receive a free newspaper subscription to the Washington Times (a conservative media outlet). Group C was a control group which received no free newspaper subscription. A public opinion survey was administered to all subjects after the 2005 Virginia gubernatorial election. Those receiving the subscription to the Washington Post were eight percentage points more likely to have voted for the Democrat than those in the control group. A subscription to the Washington Times produced no change in voting behavior relative to the control group. Did this field experiment have internal and external validity? What, if any, are the limitations? Experiments are the “gold standard” for research in political science. However, many research questions are not suited for conducting experiments. As political scientists we study concepts as we find them naturally in society. We generally cannot manipulate variables such as people’s party id, their relative liberalism, a state’s level of economic development, a nation’s institutional design, people’s gender, or education levels. The list is long of the things we would find difficult to manipulate in an experiment, but which are deemed important political variables. Hence, we must often rely on observational studies. An observational study is one in which we make controlled comparisons of data where we find it. In some cases we use surveys based on random selection of respondents from a population. Then, we compare groups in this randomly selected sample. However, if randomization is not complete, there may be factors which “creep into” our observational studies which can affect the outcome. One potential problem is generally labeled “selection bias.” Selection bias occurs when subjects find their way into the treatment group based on some systematic factor relating to the dependent variable. Examples: It was widely predicted in 1948 that Thomas Dewey would win the 1948 presidential election over Harry Truman. These predictions were based on telephone surveys of respondents voting intentions prior to the election. Why were they wrong? Suppose we conduct an observational study of how a person’s income affects their propensity to vote. However, our sample contains only respondents from neighborhoods where people could be safely surveyed. As a result, we have too few low income respondents in our sample. What is the result of this procedure? Wood and Vedlitz (2007) conducted a survey experiment concerning the determinants of people’s views on global climate change. At the start of the survey, they asked people how concerned they were about various issues facing the nation. The issues included global terrorism, global climate change, the economy, discrimination, deteriorating moral values, etc. At this stage people had no idea that the researchers’ primary interest was their level of concern about global climate change. About 30 minutes into the survey after questioning people about various issues, people were randomly selected to receive three different scenarios. The three groups randomly received the scenarios: Suppose I told you that 70/50/30 percent of Americans believe that global climate change is a serious problem. Respondents were then asked how concerned they are about the issue of global climate change. Comparing the scenario responses to the pre-measured level of concern, those receiving the high treatment (70) were more concerned about global climate change than those in the mid-treatment (50), who were more concerned than those in the low treatment (30). The authors claimed that this difference suggested the importance of social pressure to people’s level of concern. A controlled comparison is accomplished by examining the relationship between an independent and dependent variable, while holding constant other variables, especially those suggested by rival explanations. Returning to our example of “support for guns on college campuses.” Our theory says that this support is based on a person’s party identification. However, a rival explanation is gender determines support. How could we evaluate which is correct? We could look at support for guns on campus only among women, and only among men. If it differs between Republican and Democrat women, and it differs between Republican and Democrat men, then we would know that partisanship is an important explanation. More generally, we can also accomplish the same thing statistically, rather than by splitting the sample into women and men. You will learn how to do this in future weeks. For now, it is enough to note the concept. This brings us back to our earlier discussion of causality, spuriousness, mediating relationships, and interactions. Here, Gender affects Partisan ID and Gender affects Gun control opinion. If the relation between X and Y disappears when Z enters the relationship, then we say the relation between X and Y is spurious. One way of seeing a spurious relationship is simply to construct a graph of the two groups. Above we can see that Republican and Democrat women are about the same in their opinions about gun control. Similarly, men Republicans and Democats are also similar. Therefore, the relationship between party id and opinions on gun control is spurious, fully determined by gender. However, suppose that Gender does not fully explain both partisan id and opinion on gun control. Then we can say that Gender both directly and indirectly affects opinion on gun control. Gender affects gun control opinion directly (Z to Y). It also affects gun control opinion indirectly (Z to X to Y). The two effects are called additive. Here is the same line chart as before, but showing that partisanship affects gun control opinion. Note that the two lines are parallel. However, this need not be the case. The relationship can also be “interactive.” Imagine a scenario in which support for gun control is such that women do not differ by partisanship, but that men do differ by partisanship. We call such a relationship an “interactive” relationship. In other words, gender affects support for gun control, but partisanship only affects it for men.