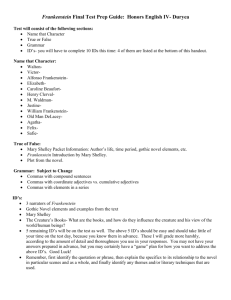

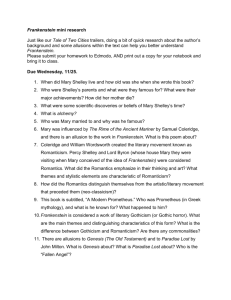

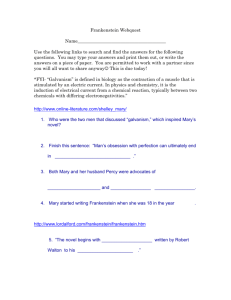

Frankenstein Presentation for Dr. Dick's Science lab class

advertisement

"Frankenstein"--today the very name sends chills down our spines. Mary Shelley was only 18 when she began to write the novel What influenced Mary to use “Frankenstein” for the name of her protagonist? Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus (1818) • • Mary Shelley’s novel was an immediate literary success and has not been out of print since 1818. People are intrigued by the horror in the novel, written by a teenager who was inspired by a nightmare (which Shelley called her “waking dream”); • • • More significantly, ever since its appearance, the novel has challenged our basic conceptions and assumptions about science and life (Brown, 1994). In it, she created the forerunner to two literary genres--science fiction and horror fiction. On the other hand, it was both a representative romantic adventure written during the Romantic Period and a critique of Romanticism. • [B]oth the media and the average person in the street have mistakenly assigned the name of Frankenstein not to the Frankenstein is our maker of the monster but to his culture's most creature. . . . [T]his "mistake" penetrating literary actually derives from an analysis of the intuitively correct reading of the psychology of modern novel. Frankenstein is our culture's most penetrating "scientific" man. literary analysis of the psychology of modern "scientific" man, of the dangers inherent in scientific research, From Anne K. Mellor, Mary Shelley: and of the exploitation of nature Her Life, Her Fiction, Her Monsters. and of the female implicit in a technological society. Keith Burns, Archivist/Collector: "What we get in the movies is the male version: the monster, the blood, the screaming, the fights, the struggle, the fire.... Whatever we get from the visual is the male element." Dr. Stephen J. Gould, Dept. of Comp. Zoology, Harvard University: "If you just saw the film, you would miss the primary moral seriousness of the entire book which is the responsibility that we all have to the things we make with our own hands." Why read Frankenstein in a biology course lab? • Shelley’s novel correlates with the subject matter--genetics, embryology, biochemistry, and cell biology--particularly well since the novel can be read not only as a political and feminist critique of nineteenth-century European society in general, but more specifically as a penetrating literary critique of the psychology of modern "scientific" man. • Thus, the dangers inherent in scientific research and current ethical dilemmas can be discussed, giving students the opportunity to consider the consequences of genetic engineering, gene therapy, reproductive technologies, human embryo research, and cloning. For science students, the novel is significant in that it incorporated the current science of her time. Mary Shelley based her work upon an extensive understanding of the most recent scientific developments of her day— specifically, that of Humphry Davy, Erasmus Darwin, and Luigi Galvani. Humphry Davy • Humphry Davy of the Royal Institution of Science published A Discourse, Introductory to a Course of Lectures on Chemistry in 1802; Mary Shelley read this work on Monday, October 28, 1816, just before working on her story of Frankenstein. • Her husband Percy Shelley then obtained Davy's textbook, Elements of Chemical Philosophy (London: 1812), for her to read further on the subject. • Davy, in his celebration of the powers of chemistry, asserted that "the phenomena of combustion, . . . of the agencies of fire; . . . and the conversion of dead matter into living matter by vegetable organs, all belong to chemistry." • Davy introduces the very distinction Mary Shelley wishes to draw between – the scholar-scientist who seeks only to understand the operations of nature and – the master-scientist who actively interferes with nature. Erasmus Darwin, grandfather of Charles • In contrast to Davy, Erasmus Darwin provided Mary Shelley with a powerful example of what she considered to be "good" science, a careful observation and celebration of the operations of all-creating nature with no attempt radically to change either the way nature works or the institutions of society. • Percy Shelley acknowledged the impact of Darwin's work on his wife's novel when he began the Preface to the 1818 edition on of Frankenstein with the assertion that "the event on which this fiction is founded has been supposed, by Dr. Darwin, and some of the physiological writers of Germany, as not of impossible occurrence" (1). • Mary Shelley, in her Preface to the 1831 edition, referred to an admittedly apocryphal account of one of Dr. Darwin's experiments (the “piece of vermicelli in a glass case [that] by some extraordinary means began to move with voluntary motion”) More Darwin • Erasmus Darwin was most famous for his work on evolution and the growth of plants, • The basic tenets of Erasmus Darwin's theories in his major works, The Botanic Garden (1789, 1791), Zoonomia; or the Laws of Organic Life (1793), Phytologia (1800), and The Temple of Nature (1803). • For English readers, Darwin was the first to synthesize and popularize the concept of the evolution of species through natural selection over millions of years (the definitive theory of this concept was later expounded by his grandson, Charles Darwin). • By 1803, Darwin had accepted, on the basis of shell and fossil remains in the highest geological strata, that the earth must once have been covered by water and hence that all life began in the sea. • Erasmus Darwin anticipated the modern discovery of mutations, noting in his discussion of monstrous births that monstrosities, or mutations, may be inherited. Electricity/Galvanism/Luigi Galvani • Lastly, in her depiction of science’s attempt to create human life ("a spark” infused “into the lifeless thing" [Shelley 38]) as a transgression against the very essence of nature, Shelley explicitly associated electricity with galvanism. • Shelley and most of Europe were aware of the work of Luigi Galvani, who in 1791 published Commentary on the Effects of Electricity on Muscular Motion, in which he came to the conclusion that animal tissue contained a heretofore neglected innate vital force, which was subsequently widely known as "galvanism." The most notorious demonstration of galvanic electricity took place on January 17, 1803, when it was applied to the corpse of the murderer Thomas Forster • Several experiments on the severed heads of oxen, frogs legs, dogs' bodies, and human corpses were subsequently replicated widely throughout Europe in the early 1800s. • Here is the scientific prototype of Victor Frankenstein, restoring life to dead bodies. Electricity's seeming ability to stir the dead to life gave the word galvanize its own special flavoring, as this 1836 political cartoon of a "galvanized" corpse suggests. Technology’s Monster • Shelley clearly saw that uninhibited scientific and technological development, without a sense of moral responsibility for either their processes or products, could easily, as in Frankenstein's case, produce monsters. • Implicit in Shelley's novel is the same warning to our day. The United States National Library of Medicine (NLM) has taken the novel’s application to scientific research seriously enough to create an exhibit on their web site. • In the Frankenstein: Penetrating the Secrets of Nature < http://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/frankenstein/index.html > exhibit, the NLM recognizes that Mary Shelley's novel expresses our natural human fear in response to new scientific discoveries which may threaten our existence or make us re-examine our assumptions about human life. • They cite as examples the atomic bomb, interspecies organ transplants, genetic engineering, and cloning. • These breakthroughs have raised the following fundamental questions about scientific research: • What is "acceptable" science and medicine? Who decides? Questions • How can society balance the benefits of new medical discoveries against ethical or spiritual questions they may pose? How can society balance the human urge to know and understand against problems arising from that knowledge? • More specifically in regard to transplanting animal organs into humans, what are the public health risks, such as the transmittal of animal viruses to humans? Or in reference to cloning, can we let scientists proceed without constraint? • Dare we embrace such a breakthrough's benefits heedless of its risks? In either situation, should we consider the moral aspect of usurping the "natural" order? Although many of these issues currently remain unresolved, for the most part they are openly debated. • However, many people today are concerned about some biomedical research that is being kept private because failure to make results of research open to public scrutiny often leads to dangerous consequences. • This is one of the lessons of Mary Shelley's novel. • Victor Frankenstein conducted his great experiment in secret; immediately upon bringing the creature to life, he abandoned it; he allowed the creature then to escape into the unsuspecting world at large, to fatal result: this led directly to his brother William's murder by the creature; still unwilling to acknowledge publicly his activity, he allowed the innocent Justine to be hanged for the crime. The National Library of Medicine exhibit illustrates the importance of public debate to reach a social consensus on issues involving scientific research with the following two cases. • The Visible Human Project began in 1993. • Gaining full permission prior to his execution, the program dissected the body of a condemned murderer and posted slides of small tissue sections to the Internet. • There they are used for educational purposes but are available to the public for viewing. In this instance, society endorsed the project. • However, in 1997 when the fact that Scottish researchers had cloned the sheep "Dolly" became public, Americans began an intense public debate of the issues surrounding cloning. • As a result, President Clinton asked the National Bioethics Advisory Commission to investigate and make a future recommendation for standards; in the meantime, he issued a moratorium on human cloning. A nuclear weapons-infested globe readily poised to destroy itself does all too easily seem like a threatening fulfillment of Mary Shelley's prophetic “Frankenstein Idea.” • An excerpt from Fathering the Unthinkable: Masculinity: Scientists and the Nuclear Arms Race (Pluto Press, London, 1983: 28, 35), by ex-nuclear physicist and science historian Brian Easlea The violation of life on this planet has reached epidemic proportions, and much of the blame for this state of affairs must be laid at the feet of those who find an endless thrill of excitement in scientifically “penetrating” the “secrets of nature,” taking little or no responsible account of the damaging implications “theory” might have for “practice.” Too often it seems the lure of power, profit and a so-called “security” of nations obscures any elements of “real disinterestedness, toleration and a clear understanding” that may have been present at the beginning of a theoretical scientist's practical researches. We should perhaps hope that the “sexy” lure of scientific penetration need not have the cold kiss of death waiting behind it. The question was "so very frequently asked me--'How I, then a young girl, came to think of, and to dilate upon, so very hideous an idea?'“ What influenced Mary to use “Frankenstein” for the name of her protagonist? Mary Shelley's father was the radical philosopher William Godwin • His Political Justice (1793) offers a criticism of existing society, a system of social ethics, and a series of prophecies for the future. • Godwin’s optimism was founded upon a confidence in the power of the human reason and the possibility of limitless development in the right direction • This belief is exemplified by his famous assertion: “What the heart of man is able to conceive, the hand of man is strong enough to perform.” • He believed that the pursuit of knowledge needed no sanction because education will lead the individual to adapt his own interests to the common good. • This moral "enlightened self-interest" corresponds to the political "will of the majority " (Baugh 1112-14) Mary Shelley’s mother was Mary Wollstonecraft, a leader in the early feminist movement • • • • She was the author of A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792), in which she argues for equality of education for both sexes and state control of co-education. Before her marriage to Godwin, Wollstonecraft had several affairs; the most notable one was with an already married American, Gilbert Imlay and resulted in the birth of a daughter Fanny. In 1793, she renewed a friendship with the well-known philosopher William Godwin. Both had publicly opposed the institution of marriage, but when she became pregnant with Mary, they married a shortly before her birth. Unfortunately, she died of complications ten days after giving birth to Mary in 1797. • A Vindication of the Rights of Women is still read in women's studies classes today Despite these illustrious parents, Mary had a difficult youth. • • • • • • After the death of his first wife, Godwin married a Mrs. Clairmont in 1801, who had two children, Charles and Jane (or "Claire, who was approximately the same age as Mary). In 1805 William and Mrs. Godwin open a publishing firm and bookshop for children's books, but, a poor businessman, Godwin experienced serious financial difficulties the rest of his life. An adversarial relationship developed between Mary and her stepmother, and in 1811 the young girl spent several weeks at Bath for sea-water treatment for a bad rash on her arm. After returning home and her relationship with Mrs. Godwin not improving, in June 1812 William Godwin arranged for Mary to stay in Scotland with acquaintances--the Baxter family. Except for spending November and December of 1812 with her family in London, Mary continued to live with the Baxters in Scotland until March, 1814 (from the age of 14-16). Mary's stepsister, Fanny Imlay, who was under the pressure of financial problems and depression, took her own life in October 1816. Mary’s future husband was Percy Bysshe Shelley, destined to be one of the great poets of the Romantic Period • As a young student, Shelley was expelled from Oxford in 1811 for writing the essay The Necessity of Atheism • In January of 1812, Shelley wrote a self-introductory letter to Godwin, assuming the role of disciple to the philosopher. • In October 1812—while Mary was still in Scotland--Percy Shelley and his wife, Harriet, met and dined with the Godwins at Skinner Street. • When Mary returned briefly to London in November, she first encountered the young poet, accompanied by his wife, Harriet, who was visiting her father, William Godwin. Unlike her unfortunate stepsister Fanny Imlay, Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin was far more flamboyant and escaped the family through rebellion. • • • On May 5, 1814, Percy Shelley returned without Harriet to dine at Skinner Street and saw Mary for the second time. They begin spending nearly every day together. By the end of June Mary declared her love for Percy Shelley at her mother's grave in St Pancras churchyard. While estranged yet still married to the pregnant Harriet, on July 28, 1814, Shelley abandoned her to elope with sixteenyear-old Mary to Europe, accompanied by Mary's stepsister Jane (later called Claire) them. Godwin denounces his daughter. • • • • Percy, Mary, and Jane spend two months in a Europe devastated by the Napoleonic Wars, traveling through France from Calais to Switzerland. Financial troubles force the trio to return to England in September. Part of the motivation for returning was Percy’s expectation of an inheritance following the death of his grandfather. However, Percy’s father, incensed with his son, prevents him from receiving the estate, dooming Percy and Mary to continuing financial troubles. Mary gave birth prematurely to a baby girl called Clara on February 22, 1815, but the infant died a few days later on March 6. Mary and Percy’s second child, William, was born January 24, 1816. Switzerland again, Lord Byron and the Ghost Writers' Contest, Back to London • • • • After their return to England, Mary’s stepsister Claire—determined to have a poet of her own--successfully pursued the notorious Lord Byron and becomes his mistress. Because of his notoriety—and maybe because he was tiring of Claire—Lord Byron found it convenient to leave London in the early spring of 1816 for Switzerland, where he leased the Villa Diodati at Coligny. In May of 1816, Mary, baby William, Percy, and Claire traveled to Switzerland to join Lord Byron on Lake Geneva and move into a nearby cottage. The inclimate summer of 1816 left the visitors ensconced in the Villa reading and telling one another Gothic German ghost tales. • • • • On June 15, the group engaged in discussions about philosophy and the principle of life, and Byron suggested that they individually write a supernatural tale. On June 16, Mary has her “waking dream," which becomes the germ of Frankenstein, and she begins to write her story. Other than Mary's classic, the only other extant story from this occasion is John Polidori's reworking of Byron's tale entitled The Vampire: A Tale. (Mary and Percy returned to England in Sept.; Fanny Godwin committed suicide on Oct. 9 and was buried anonymously, Godwin having refused to identify or claim the body; Harriet Shelley's body, advanced in pregnancy, was found in the Serpentine river on Dec. 10, where she had drowned herself; Mary Godwin married Percy Shelley on December 30.) Why did Mary Shelley have such a dream at this point in her life? • • • • • • Over fifteen years later, she claimed she could still see vividly the room to which she woke and feel "the thrill of fear" that ran through her. Why was she so frightened? Mary Shelley had given birth to a baby girl eighteen months earlier, a baby whose death two weeks later produced a recurrent dream: "Dream that my little baby came to life again; that it had only been cold, and that we rubbed it before the fire' and it lived. Awake and find no baby." The 1816 reverie unleashed her deepest subconscious anxieties, the natural but no less powerful anxieties of a very young, frequently pregnant woman, so she once again was dreaming of reanimating a corpse by warming it with a "spark of life." And only six months before, Mary Shelley had given birth a second time, to William (who, ironically, would die of malaria within 3 years—6/7/1819). She doubtless expected to be pregnant again in the near future; and indeed, she conceived her third child, Clara Everina, only six months later in December. (This child died a year later [9/24/1818] of a fever.) We might also note that the nightmare motif made a significant impact on her. In 1792 her mother Mary Wollstonecraft offered to enter a ménage a trois with the Romantic painter and intellectual Henri Fuseli and his wife, but was refused. “The Nighmare” by Henri Fuseli “The Nightmare” is one of Fuseli’s most memorable and striking paintings. Anne Mellor observes that Mary knew the painting very well, and several critics have suggested that the description in Frankenstein of the death of Elizabeth Lavenza on her wedding night is based on it (121). Ben Franklin’s Experiments with Electricity • Given the importance of electricity as an animating force in the novel, most readers, particularly her immediate audience of the early 1800s, would connect the name Frankenstein with Ben Franklin. All Europe was familiar with Ben Franklin's recent experiments with electricity and Mary included a direct reference to him in the first edition of the novel. • • • • • In 1747 Benjamin Franklin began the electrical experiments He developed a battery composed of eleven large glass plates covered with sheets of lead. While several investigators--Wall, Newton, Hauksbee, Gray, and others—had noted the resemblance between electric sparks and lightning, Franklin proved their identity. In June, 1752, as a thunderstorm began, he sent up, on strong twine, a kite made of silk (as better fitted than paper to bear wind and moisture without tearing); a sharply pointed wire projected some twelve inches from the top of the kite; and at the observer's end of the twine a key was fastened with a silk ribbon. The result demonstrated “the sameness of the electrical matter with that of lightning completely.” In the first edition of Frankenstein, Victor is introduced to the recent discoveries of Benjamin Franklin by his father (24-25). But she didn't just make up a German name that sounded like the Anglican Franklin. Frankenstein is the name of an old aristocratic German family The name literally means “the stone of the Franks.” The Franks were a Germanic people who settled in Western Europe during the decline of the Roman Empire This particular Frankish family settled near a stone quarry (in the vicinity of what is now Darmstadt, Germany), so they became known as the Frankensteins. Mary passed their ruined castle on her way home from Europe in 1814. The history of the Frankensteins included several Romantic heroes While the novel may be a critique and a parody of Romanticism on one hand, it also very much embodies Romantic values--particularly that of the Romantic hero. • Arbogast Baron von Frankenstein was a victorious fighter from that area and erected a castle in the thirteenth century. • One of the knights in the sixteenth century, Sir George Frankenstein, according to legend, sacrificed his life slaying a dragon. Before he died, however, he was able to save beautiful Annemarie, "The Rose of the Valley." Clearly, the novel is concerned with the search for secret knowledge and the creation of life, and the historical Frankensteins also had a connection with these issues. • Fortuitously, the philosopher's stone--a term associated with alchemy and Paracelsus--is also suggested by Frankenstein-- "FranksStone." • The philosopher's stone is the magical substance in alchemy which brings about the transmutation of metals, a cure for all ills and immortality. • Eventually the Philosopher's Stone was thought to signify the force behind the evolution of life and the universal binding power which unites minds and souls in a human oneness. Another legendary figure was Johann Konrad Dippel (1673-1734) who was born in the castle. He studied Paracelsus and lived his life searching for knowledge as a wandering scholar and alchemist. He would sometimes sign his works "Frankensteina," and claimed to have the secret of the philosopher's stone, as well as the ability to create life. Significantly, Mary has her protagonist study the works of Paracelsus as a youth. Also, the Frankenstein Castle ruins no doubt served as a magnet to travelers of romantic temperaments and interest in legends. The site and its history had an inspirational effect on Johann Goethe and his Faust. Goethe spent part of his youth near the Frankenstein Ruins, and over a 30 year period worked on Faust, an epic poem about the quest for selfknowledge. In Goethe's epic, the hero sells his soul to the devil in seeking the secret of life; he creates an artificial man in his laboratory. Mary was very familiar with Goethe and his works. As a young girl, she often listened in on the conversation of William Godwin's intellectual circle. Likely she heard Crabb Robinson report that he had discussed Godwin with Goethe while he was in Germany. We know that in 1815 she read Goethe's tremendously culturally influential The Sorrows of Werther, and then before she conceived of Frankenstein in the summer of 1816, she read de Stael's review of Goethe's Faust with its over-reaching philosopher. The need of carefully considering consequences before acting is ironically implied in Shelley’s subtitle for the novel: The Modern Prometheus. • Several critics have commented on the obvious allusion in that the titan Prometheus is credited with two significant acts: creating humans from clay and stealing fire from the gods and giving to man as a protectivesustaining gift. • Shelley combines these attributes in Frankenstein: he creates (recombines from used body parts) a being, animating it with fire (electricity). • However, a fuller consideration of the Prometheus myth, as explained by Hamilton (1942), deepens the significance of the allusion, especially in regard to the issues of actions/consequences/responsibility. Prometheus (“forethought”) • In Greek, the name Prometheus literally means “forethought,” for the titan was very wise. • After his brother failed in the task of creation, Prometheus perceptively discovered a way to fashion humans from clay and then to provide for their most basic needs by giving them the stolen fire. • Furthermore, aware of the risks, he willingly sacrificed himself for the good of others. Zeus, angry at the theft, had Prometheus chained to the side of a mountain and a vulture tore at his liver continuously. Epimetheus (“afterthought”) • In contrast, the titan’s brother was named Epimetheus, which means “afterthought.” • Epimetheus frequently acted on thoughtless impulse, only to regret his actions later. • Given by Zeus the responsibility for creation, he squandered all the good gifts on animals and had inadequate qualities left for the making of humans. • Too late, as always, he was sorry and asked his brother's help. • Later, despite a warning from Prometheus, Epimetheus accepted from the gods the most beautiful woman ever created--Pandora, "the gift of all.” • Unfortunately, the gods also gave Pandora a box containing all the evils in the world, which she opened, releasing them. • Thus disregarding reasonable caution, Epimetheus eagerly acted to possess what he desired, indirectly causing all the miseries in the world (Hamilton, pp. 85-93). What genre of literature best describes the Frankenstein tale? • Gothic? • Science Fiction? Gothic Tales • macabre, fantastic, and supernatural • usually set amid haunted castles, graveyards, ruins and wild picturesque landscapes • they reached the height of their considerable fashion in the 1790's and the early years of the 19th century (Oxford Companion to English Literature 405-06) Science Fiction • A prose narrative which • either assumes an imaginary technological or scientific advance • or depends on an imaginary and spectacular change in the human environment • (Oxford Companion to English Literature 876) Gothic elements in Mary Shelley's novel. • She was familiar with the classics of Gothicism: Mrs. Radcliffe's The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), M.G. Lewis's The Monk (1796) and William Beckford's Vathek (1786). • In common with these Gothic tales, Frankenstein made use of the correspondence between theme, character and setting. • One of the chief elements in the novel is the use of atmosphere to create mood. The icy mists of the Arctic and the bleak windswept Alpine glacial fields are linked to the spiritual and social isolation of the Creature and its Creator. • Not unlike Victor Frankenstein, Gothic heroes are trapped in gloom unable to appreciate the light of day. They are the descendants of Cain, Satan, and Prometheus--heroic in their rebellion yet pathetic in their destiny. • In order to depict the shadow-side of their heroes, Gothicists used ghostly visitations, especially a device known as a doppleganger, a mirror image of the self. Creator and Creature in Frankenstein are in reality one self, reflecting different sides of human personality. Narrator--1st person, but shifts • Vol. I, Letters I-IV (1-18): Walton, Letters to Sister Margaret, making a • • • • • • manuscript of conversation with Victor Frankenstein ("This manuscript will doubtless afford you the greatest pleasure.... "[ 18]) Vol. I, Chps. I-VII (19-68): Frankenstein, via manuscript Vol. II, Chps. I-II (69-79): At the end of chapter II, Frankenstein: "But I consented to listen; and, seating myself by the fire which my odious companion hated lighted, he thus began his tale" (79). Vol. II, Chps. III-VIII (79-118) : The Creature Vol. II, Chp IX; Vol. III, Chps. I-VII (118-78): Frankenstein, via manuscript Vol. III to end (178-91): "Walton, in continuation"--Letters to Margaret Irony of narrative structure: the beginning, end, and climactic moment occur in an ice field Mary’s Reading List: Between January 1815 and the summer of 1816, the eighteen months before she conceived Frankenstein, Mary Godwin read some ninety works. • • • • One important course was her study with Shelley of the major English poets: Spenser, Shakespeare, Milton, Coleridge, Wordsworth, Byron, and Southey, as well as Scripture for its poetry. Her other reading included The Canterbury Tales and Godwin's Life of Chaucer, William Beckford, Samuel Richardson, Joanna Baillie, Matthew "Monk" Lewis, Walter Scott, Ann Radcliffe; she also read Goethe and Schiller in translation, Shelley having interested her in German literature. In history and related fields she read Gibbon's Decline and Fall and his Life and Letters, Edward Clarendon's History of the Civil Wars, Edmund Burke's Vindication of Civil Society, William Robertson's History of America; memoirs of modem philosophers, historically important figures, and travelers, such as Admiral George Anson's narrative of his voyage around the world and Carl Phillipp Moritz's Tour of England. • • • • She read Voltaire, d'Holbach, and the major works of Rousseau and de Stael in the original, and, with Shelley tutoring, Ovid, Sallust, Virgil, Quintus Curtius, and Petronius ("detestable," she noted). She would become an accomplished scholar in Latin and Romance-language literature." She studied Italian and Greek through the Iliad and the satirist Lucian, aided by Shelley, translations, and lexicons. In addition, the lovers followed current political-literary debates in the major arbiters of taste and opinion, the Tory Quarterly and Whig Edinburgh Reviews. Remember, this reading was done by a17-18 year-old girl who had no formal education. Videos • • • • • • • • Frankenstein (The Restored Version). Starring Boris Karloff, Colin clive, Mae Clarke, John Boles, Edward Van Sloan, and Dwight Frye. Based on a story by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley. Adapted by John L. Balderston from a play by Peggy Webling. Screenplay by Gsrrett Fort and Francis Edwards Faragoh. Directed by James Whalen. Produced by Carl Laemmle, Jr. Orginal Theatrical release: Universal Studios, 1931. Restored Video release: August 22, 1991. Run Time: 71 minutes. Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (Widescreen Version). Kenneth Brannagh, Robert DeNiro, Tom Hulce, Helena Bonham Carter, Aidan Quinn, Ian Holm, John Cleese. Columbia Tristar, 1994. RT: 123 minutes. Young Frankenstein. Gene Wilder, Peter Boyle, Marty Feldman, Cloris Leachman, Terri Garr, and Madeline Kahn. Directed by Mel Brooks. Twentieth Century Fox, 1974. RT: 106 minutes. The True Story of Frankenstein. Hosted by Roger Moore. Narrated by Eli Wallach. Interviews with Robert DeNiro, Kenneth Brannagh, Francis ford Coppola. 1994. RT: 100 minutes. Haunted Summer. Philip Anglim, Laura Dern, Alice Krige, Eric Stoltz, and Alex Winter. Cannon, 1988. RT: 106 minutes. Gothic. Starring Gabriel Byrne, Julian sands, Natasha Richardson, Miriam Cyr, and Timothy Spall. Screenplay by Stephen Volk. Directed by Ken Russell. Virgin vision and Vestron Pictures, 1986. Run Time: 87 minutes. The Bad Lord Byron. International Films series. Timeless Video, 1949. RT: 95 minutes. Percy Bysshe Shelley. The Famous Authors Series. Kultur, n.d. RT: 30 minutes.