Federalism, Tax Base Restrictions, and the Provision of

advertisement

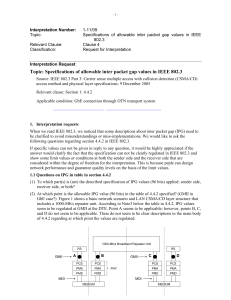

Federalism, Tax Base Restrictions, and the Provision of Intergenerational Public Goods Paper (John Hatfield) Comments (Greg Burge) Competition and Subnational Governments, April 25th-26th, 2014, Knoxville, Tennessee Summary of the paper • Drawing on the capitalization effects of IPGs on land values, the current generation’s ability to finance IPGs through debt to be paid back by future generations, and the current value of land being influenced by both the burden of future taxes and the benefits of future IPG consumption, the model developed shows that under certain conditions the efficient level of IPGs will be provided even though the current generation does not (directly) experience the full benefit of their consumption. – Local governments invest more efficiently than central governments regardless of the tax instrument – Head Taxes achieve efficiency even if the presence of limited competition and congestible IPGs while land taxes do not, but land taxes approach efficiency for pure non-rival IPGs with many districts. Implications • Argues for rethinking the connection between “big” (central) government and “big” (durable, intergenerational) public infrastructure. • Competition may trump the central governments ability to deal with crossjurisdiction externalities. Overall Reactions • Strong paper, solid defense of claims. • Some additional topics could potentially be touched on through further comments in the paper, others may be better left for future extensions. Cost Sharing Agreements • Various types of sub-national cost-sharing agreements (local-local, state-local, state-state) are common ways of handling spillovers that are considerable in magnitude. • For example, the State of New York DOT just entered into an agreement with AMTRAK. The article outlined how – “New York has already completed a separate agreement to share costs with Vermont on the Ethan Allen line, which carries passengers between Albany and Rutland, Vt.” Different Types of IPGs? • Certain types of local infrastructure (transportation systems, buildings, land preservation) are immobile. • Local government’s also invest in durable human capital (education, health & human services, job training). The costs are often labor costs, not capital expenditures. But studies show the rate of return to human capital is just as high as the rate of return to physical capital. • The human capital (youth) that local jurisdictions invest in is mobile though, and can leave the jurisdiction. Efficiency in investing in these local services? Equity Issues • In the model, IPG is simply in the jurisdiction, it does not have a location per se. [So in turn, the price of land is a value, not a gradient.] • 2nd generation pays based on land values, so they do not gain/lose based on where the IPG is located. • 1st generation winners/losers. Reversibility & consuming the IPG • The IPG was irreversible here, which makes sense in most general cases. • Capital Facilities that have value to the private sector could conceivably be sold by future generations to increase their consumption of the private good. • In more general terms, the real world application of this theory would suffer if the current generation had an imperfect signal of the future generations willingness to pay for the IPG. Used Local Revenues • Mentions the lack of head taxes and land taxes in concluding remarks. – Property taxes – Local sales taxes – State income taxes – Local Impact Fees – Ability to reach efficiency in IPG provision is linked with the influence on land values in any case.