Dias nummer 1

advertisement

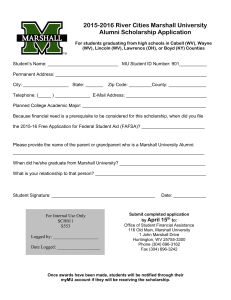

Alfred Marshall (1842 – 1924) and Francis Ysidro

Edgeworth (1845 – 1926)

The two leading late 19th century British economists

1

Marshall and Cambridge, first professor of

economics

Always seen as something special: his analysis is easier to

follow than, say Walras’, as his approach is ”plain English”.

Seen as someone that was the beginning of the Cambridge

tradition: Marshall, Pigou, Robertson, Keynes, Sraffa,

Austin Robinson, Joan Robinson, Kaldor, Robert Neild,

Frank Hahn, Angus Deaton and many, many more.

Marshall was a well-trained mathematician. “Burn the

mathematics when the analysis is done, then “plain

English”.

No doubt that his foremost pupil, John Maynard Keynes,

thought that Marshall was a giant. In 1933, Keynes wrote

an essay on Marshall and his economics – referred to by

Sandmo. This essay together with similar articles on other

economists are impressively well researched and

composed. Moving social profiles.

Marshall was a bit strange: very conscious of offering polite

words to his colleagues and competitors but often with a

tone of jealousy. It took him 20 years to write his main

work, Principles of Economics (1890)

2

What did Marshall accomplish?

Marshall is the inventor of several important concepts: The

Partial Equlibrium Method, elasticity, the interrelation

between market equilibrium and social welfare , ceteris

paribus and more. He uses supply and demand in the

same way as we do.

Principles was a textbook – perhaps the first modern one –

and it is large (871p); economic theory is in Book 5.

3

The Marshallian cross 1

From p. 346 in a footnote! – what is so great about that?

4

The Marshallian cross 2

Now what is so great about this?

Demand based on decreasing marginal utility – as in Jevons

and Walras – but much clearer.

Supply curve rising due to increasing marginal costs. Very far

from the classical conception of a flat supply curve (Labour

theory of value, determining the price alone)

“We might reasonable dispute whether it is the upper or

under blade of a pair of scissors that cut a piece of paper,

as whether value is governed by utility or cost of

production” (p. 348) – General equlibrium as in Walras?

Probably, but illustrated partially, only one market at display.

Much easier to understand and makes adjustments clearer.

In the short run, supply may be vertical, price increases

with demand, but in the longer run supply becomes flatter.

As Sandmo explains, this was an important piece of

analysis that Keynes took over.

5

Partial or general equlibrium?

Walras had a model of all markets; it determines all quantities

and all relative prices. Is Marshall doing the same?

He invented ceteris paribus to do one market at a time. He

also have many remarks on the interrelationships of all

markets. Also clear, that Walras’ model could not take into

account all the particularities of each individual market.

Marshall’s method is very practical – very useful to go from

market to market. Ref. i.e. Tobin who talked about

monetary theory in his path-breaking 1969-article it was

called “A General Equlibrium Approach to Monetary

Theory”, but it was partial as only monetary markets were

considered. So, it is used a lot. In addition, no one

analyzing a small market would try to put it into a

complete setting. However, did Marshall really understand

interdependencies? Perhaps he did not is Sandmo’s

conclusion and that is not so innocent.

He understands substitution effects but maybe not income

effects.

6

Utility, demand and welfare 1

Marshall understands that a decreasing MU will lead to a

decreasing demand curve. Higher price, lower demand.

However, a lower price will also increase the purchasing

power of the person’s nominal income. The MU of the

income increases and we not only have a substitution

effect (higher price, lower demand) but also an income

effect (a higher real income can buy more of all goods).

Now, Marshall assumes this away as he is only referring to

a “small” market.

7

Utility, demand and welfare 2

Now add all demand curves to get the market demand for a

particular good:

8

Utility, demand and welfare 3

The consumers’ surplus measures the gain to consumers from

a fall in price down to equlibrium. They would have been

willing to pay more but they do not have to. Similarly,

producers enjoy a producers’ surplus. Had the price been

lower, their surplus would have been lower et vice versa.

The sum of these two surpluses, Marshall calls the social

surplus and it proves to be an extremely interesting

concept.

9

Utility, demand and welfare 4

“There is indeed on interpretation of the doctrine {social

surplus at its maximum in equlibrium} according to which

every position of equlibrium of demand and supply may

fairly be regarded as a position of maximum satisfaction.

For it is true that so long as the demand price is in excess

of the supply price, exchanges, exchanges can be effected

at prices which will give a surplus of satisfaction to buyer

or to seller or to both.” (p 470). All this of great interest to

many, many kinds of applications.

Market equlibrium is a social optimum, but Marshall is aware

that one may – or should – intervene in markets to obtain

distributional effects.

10

Elasticities

Were invented by Marshall to present a way of giving meaning

to reactions or steepness. Of enormous practical use in

multiple situations! As you know well!

11

External effects. Marshall analyzing a special case only

Can the long run supply curve be downward bending so that

price will decrease with an increased demand? Yes, with

increasing returns to scale. Costs may go down when

production becomes more efficient. Demand for computers

have been rising for 30 years and they have become far

better – because of much technological progress.

Inventions etc. have cut costs. However, also the opposite,

ref. Marshall’s example with fishing.

Not quite what we would call external effects, but clearly

important. He had a “plan” for taxing firms with increasing

returns to scale and transferring to money to those with

increasing! Taxing Intel and give the money to fishermen

.

12

Factor Markets and Income Distribution 1

The Iron Law of Labour does not work anymore!

Marshall’s demand for labour:

In addition, this is influenced by training (human capital and

education). A high wage makes it possible for parents to

give their children a good start in life (Marshall’s father

persuaded his employer (Bank of England) to pay for

Alfred in a fine school!). Moral principles and Christian

ideas are somehow behind what men do!

“Cambridge is for men with cool heads and warm hearts”

Read Sandmo.

13

Factor Markets and Income Distribution

2

Upwards sloping as MU increases as w increases.

Much the same for capital, one will be investing (supplying

capital) until rate of profit equals interest rate.

14

Monetary Theory 1

Not in Sandmo. Marshall published a Money, Credit and

Banking when he was 80! It was a Quantity Theory of

Money approach, but

He is close to see M as a demand for money function and not

the supply of money, later slowly leading up to Keynes’

liquidity preference. Also Interest rate is (as we have seen)

something that can differ from the rate of profit. Wicksell

made much of that! What about the real rate of interest?

15

Monetary Theory 2

Purchasing Power parity, exchange rates adjust according to

inflation differentials and – again – the change of the

money supply.

In favor of index-linked clauses in long term contracts.

Sandmo is not very enthusiastic about his monetary theory –

can’t see way!

16

Francis Ysidro Edgeworth (1845 – 1926)

Mathematical economist concerned with the interactions

between equlibrium and welfare.

.

What is utility? How to measure it and compare between

individuals?

We saw that economists from Cournot, Mill etc. discussed

utility and that Marshall intuitively argued that marginal utility

was negative and (therefore) the demand curve downward

sloping. He was also arguing that society would reach a

“maximum satisfaction” with regard to one market when it

was in equlibrium:

What is utility?

However, what is this ”maximum satisfaction?

A key to understanding this is Utilitarianism

(from Bentham). It can be measured, one can compare

between individuals and it can be aggregated!

Edgeworth worked with Exact Utilitarianism:

“We cannot count the golden sands of life; we cannot number

the “innumerable smile” of seas of love; but we seem to be

capable of observing that there is here a greater, there a less,

multitude of pleasure-units, mass of happiness; and that is

enough.”

Based on psychology, Edgeworth argued that marginal utility

of income must be decreasing.

Social welfare

My understanding of this is that Edgeworth in fact did believe

that one could compare utility between individuals! This is

believe contradicts the quote on the previous slide! Take from

a rich person an give to a poor will increase total utility; this is

what we call cardinal utility. It obviously has political

implications.

Social welfare is the sum of individual utility functions. As we

will se, Pareto had the opposite opinion while Pigou assumed

the same as Edgeworth (even though he did not care too

much). This is a very fundamental issue with enormous

consequences for politics!

Utility functions

Anyway, how do we measure the utility of one specific

individual?

As we saw, Marshall considered good after good (the partial

equlibrium approach):

Edgeworth realized that goods may be substitutes (butter and

cooking oil); consumption of one good dependent on the

consumption of another:

More consumption of x, less utility of y. Nevertheless,

obviously, it could be the other way round (university class

teaching and e-learning). What we now call complementary

goods.

Indifference curves

Coming so far, Edgeworth is the first to draw the indifference

curve (here a series of curves – each indicating a level of

individual utility

Why must these curves be

concave? Starting from a point

on one specific curve in the

North West corner, one is willing

to surrender much y to get

extra x et vice versa.

The shape of indifference curves

Why must these curves be concave? Starting from a point on

one specific curve in the North West corner, one is willing to

surrender much y to get extra x et vice versa.

Now, an exercise in transactions in a perfect equilibrium with :

There are two consumers A and B and two goods

X (first axis) and y (second axis). At the

beginning, they are in E1; A owns little x and

much y and the other way round with B. A’s

indifference curves are observed from A and B’s

from B. By making transactions both A and B can

improve their positions and obviously their utility;

both are moving to higher indifference curves. The

invisible hand working!

Sketching the perfect equilibrium

As Sandmo sketches by increasing infinitely the number of A’s

and B’s we end up with an equlibrium that is perfect

competition. This is what we call positive or descriptive

analysis.

Or on YouTube:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fAbwlxb9ffE