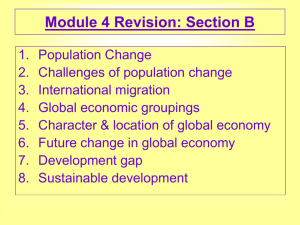

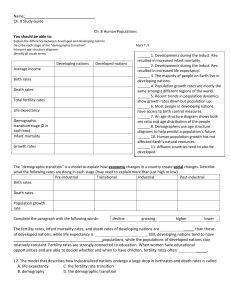

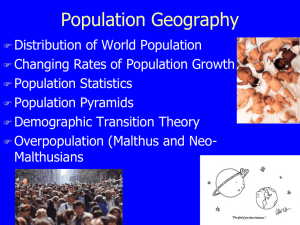

Introduction to Demography

advertisement