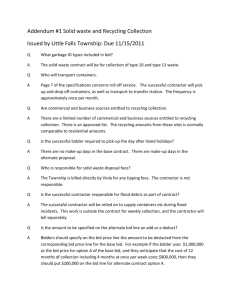

Government Contracts Outline

advertisement