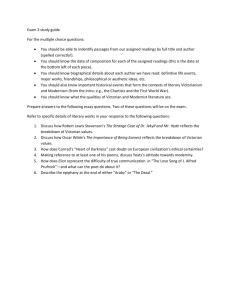

Catholicism and the Secular Victorian Home

advertisement

LaMonaca, Maria. Masked Atheism: Catholicism and the Secular Victorian Home. Columbus: The Ohio State University Press, 2008. $44.95 cloth, $9.95 CD. ISBN 978 0 8142 1084 0 (cloth), pp. xiii + 231. Reviewed by: Cheri L. Larsen Hoeckley, English Department, Westmont College, March 2012. Maria LaMonaca states early that Masked Atheism will focus ‘mostly on midcentury literary engagements with Catholicism’ (2). From that focal point, her thematic clusters of texts indubitably support her claim that ‘women writers of all Christian denominations (both Protestant and Catholic) appropriated popular Victorian notions of Roman Catholicism to articulate a shared set of anxieties about the increasing secularization of the Victorian domestic sphere’ (3). Across both denominational affiliation and literary genre, laMonaca traces how these women writers share a consistent anxiety not so much about Catholicism as about Victorian secularist tendencies, which she identifies at one point as ‘the forces of materialism, atheism, imperialism, and industrialism’ (98). LaMonaca convincingly argues that the period’s reigning domestic ideology genuinely concerned women of faith throughout the variations in Victorian Christianity’s terrain , and these women explored their concerns through writing about ecclesiastical practices and doctrine such as transubstantiation, auricular confession, religious vocation, and celibacy. Masked Atheism begins to suggest the ways that representations of Catholicism provided Victorian women writers with a safe means for imagining critiques of that hegemonic understanding of family life, particularly as it constrained female agency with respect to following Christian spiritual imperatives. As a pattern, the book’s chapters bring together pairs of texts focusing on one Catholic practice or doctrine. That structure reveals LaMonaca’s New Historicist tendencies, though her fruitful close readings also suggest her equal attention to matters of genre. On more than one occasion, for instance, she notes that through the fictional impulses of a courtship novel, Christian women writers found the opportunity to critique domestic ideology, even though they were excluded from the realm of sermons where Christian cultural critique was most commonly voiced. She also makes productive use of other Christian genre, especially the hagiography. The first two thematic chapters after the introduction each bring together one novel from Charlotte Brontë with one from Lady Georgianna Fullerton. In setting Jane Eyre along side the less remembered Lady Bird, LaMonaca explores how these two novels rewrite the marriage sermons that served as moral guides for many middle-class Victorian women. The following chapter returns to these two novelists to consider how the possibilities of auricular confession allow for more psychologically, morally and spiritually complex heroines in both Ellen Middleton and Villette. Other chapters consider anxiety about convents in a range of “forgotten’ fictional texts” (96) and also the place of transubstantiation in Aurora Leigh and Goblin Market. The final two chapters actually resist the tendency to pairs, one of those chapters focusing on the journals, conversion and domestic life of the striking domestic grouping: Kathleen Bradley, Edith Cooper and their dog Wynn Chow. LaMonaca’s efforts reach their apex in her penultimate chapter, which considers hagiography and the Virgin Mary in George Eliot’s Romola. LaMonaca’s presentation of her masterful archival research offers genuine value to this work, whether she is mentioning any number of Protestant and Catholic sermons and pamphlets, or analyzing The Experience of Life (1852) Elizabeth Missing Sewell’s “fictional apologia for spinsterhood” (96), or opting to work with the complete journals–rather than the abridged, published versions–of Michael Field (Bradley and Cooper’s joint pseudonym). Her research on Fullerton results in a rich reading of both Lady Bird and Ellen Middleton, novels more readily available than some of her other ‘forgotten’ texts, but still with minimal critical analysis until now. At a few points, readers may wish for more synthesizing analysis of how the juxtapositions of these various texts inform our understanding of Victorian Catholicism, or Victorian Christianity more broadly, or of domesticity. For instance, though LaMonaca offers some background on Fullerton’s cofounding and support of the Poor Servants of the Mother of God (36n), her readers still wonder how Fullerton’s experience with women’s orders strengthened her sense of women’s vocations outside of marriage—or, more pointedly in the case of Fullerton and Lady Bird, how that admiration for women religious strengthens, complicates, or nuances this female Catholic novelist’s sense of calling within marriage? While it is entirely possible that the archival evidence cannot support considerations of Fullerton’s inner life, LaMonaca’s larger concerns with religious motives and anxieties deepens a desire in her readers for some analysis of the material that she did find. If Masked Atheism has shortcomings, most of them are the understandable limitations of an interdisciplinary work joining two fields early in their mutual relationship. The field is not entirely new, of course. LaMonaca refers to Kimberly Van Esveld Adams’ Our Lady of Victorian Feminism (Ohio, 2001) and acknowledges her gratitude to Frederick Roden (Same-Sex Desire in Victorian Religious Culture, Palgrave Macmillan, 2003). Mark Knight and Emma Mason have made the argument in Nineteenth-Century Religion and Literature: An Introduction (Oxford 2001) that Victorian religious debates across discourses melded into secularism, often in the most devout of writers. Maureen Moran’s Catholic Sensationalism and Victorian Literature (Liverpool UP, 2007) now broadens the field of literary studies of the anti-Catholic texts that marked the mid-century, especially. LaMonaca still holds her own space as one who considers Christian women writers across denominations, with emphasis on how Catholic women’s faith and Protestant women’s imagination of the Catholic faith, equipped them to critique domesticity. Her habit of relying on initially useful, but ultimately limiting, binaries between pro- and anti-Catholic limits both LaMonaca’s readings and the possibilities of enhancing her arguments with more of her research on convents, Catholic women, as well as Protestant novels and sermons. While LaMonaca’s attention to religious converts (and to those like Eliot who left Christianity) indicates her sensitivity that various religious states coexist in the same work or in the same believer in a variety of unstable and fluctuating forms, her labels for those phenomena limit her conclusions. In short, now that LaMonaca has brought to our attention this range of women’s texts and their inter-relations, we see opportunities for complexity in her readings. And yet, her work takes the study of Victorian Catholic women and literary influence well beyond other current scholarship. Finally, La Monaca writes with a disciplined clarity that makes her work a sincere pleasure to read. Her stylistic gifts reveal themselves at their best in her chapter on Romola, “The ‘Queen of Heaven’ or a Very Confused Nun?: Our Lady of La Salette, George Eliot, and Victorian Anxieties about God” (160 – 189). LaMonaca adroitly calls on Edith Wycshogorod’s postmodern theory of hagiographies to illuminate a dense novel, gracefully offering these sentences: For Romola to perform saintly action, and for her narrative to take on a hagiographic quality, two conditions must be met. First Romola must act, not out of love or reverence for any authority or father figure, but out of spontaneous love (agape) for the Other in need. To wean Romola off her chronic dependence on human authority, the novel literally kills off all the men in her life. . . . The second condition of Romola’s ‘sainthood’ is that her benevolent actions carry with them a moral imperative for others. Although Romola, upon awakening in her little village, feeds the hungry and nurses the sick, her most significant contribution is her ability to inspire altruism in others. (184-185) Masked Atheism offers many significant contributions to the study Victorian Catholicism and literature, including the ability to inspire others to continued research.