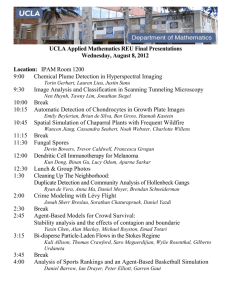

daniel

History / Evolution of Civilization

04-The Books of the Tanak

Prof.Dr. Halit Hami ÖZ

Kafkas Üniversitesi/Kafkas University

Kars, Turkey hamioz@yahoo.com

The Books of the Tanak (Old Testament)

The people of ancient Israel (the Hebrews) were, in most respects, an insignificant people during most periods of their history, but they had more impact on subsequent history than any other Ancient Near Eastern people.

This almost entirely because of one single contribution, What Jews call the Tanak and

Christian the Old Testament.

The Tanak is the basis of Christianity, Judaism, and (to some extent) Islam--the religions (at least nominally) of half the world's people.

Because religion is so important in people’s lives, this means that Tanak ideas end up reflected in just about every area of life.

One sees this perhaps most clearly in law, but it’s also true in fields like philosophy, art, music, and literature.

Philosophers from Justin Martyr to Augustine to Aquinas to Descartes to Bergson, and artworks ranging from the Medieval cathedrals to the paintings of Raphael and Rubens to the sculptures of Bernini and Michelangelo show Tanak influences.

http://www3.northern.edu/marmorsa/histor y121.htm

2

The Books of the Tanak (Old Testament)

Beyond this, The Tanak has had a lasting influence about way we think about fundamental issues of life.

It give us much of the framework within which we think about all sorts of different issues.

Each book of the Tanak, then, is important in terms of its influence on subsequent civilization.

I emphasize five representative books in class, but many of you will be able to discuss other Tanak books, and those of you who are art and music majors especially may have much to say about Tanak influence far beyond the brief notes here. http://www3.northern.edu/marmorsa/histor y121.htm

3

The Books of the Tanak (Old Testament)

[Tanak, by the way, is short for the three divisions of the

Hebrew Bible by Jewish reckoning: the Torah (law), the

Neviim (prophets), and the Kituviim (writings).

Of the books assigned in class, Genesis and Deuteronomy are part of the Torah, the Law, the five books of Moses (also called the Pentateuch).

Isaiah is part of the Neviim, the prophets, a section which, by

Jewish reckoning, consists of the “former prophets” (Joshua-II

Kings) and the “latter prophets” (books like Isaiah).

Psalms and Daniel are among what Jews call the Kituviim

(writings). Note that while Christians group Daniel with the prophets, Jews put Daniel amid the writings.] http://www3.northern.edu/marmorsa/histor y121.htm

4

GENESIS

Historians call accounts of the beginning of things creation myths.

A myth is not necessarily an untrue story, but rather a story that shows what a society considers to be the deepest truth about man and universe.

Nearly all societies tell such myths (we’ve already looked at the Sumerian and Babylonian creation myths), and one could argue that, in a certain sense, we have creation myths today: two of them widely believed in our society: the Hebrew account in Genesis and the Darwinian theory of Evolution.

It’s important to understand here that what is at stake is *not* science but two very different concepts about man and his place in universe.

Probably the best way of looking at the earliest part of Genesis, though, is

*not* as a creation myth but as anti-myth. It is a direct challenge to the polytheistic world view that dominated the Ancient world when the book was written. http://www3.northern.edu/marmorsa/histor y121.htm

5

GENESIS

In beginning, God created the heavens and the earth, says Genesis.

Note that the writer could have simply said “God created everything” and left it at that.

But the writer goes on to specify each of the things God created.

It’s important to note that many of things mentioned in Genesis one were regarded by the peoples of Mesopotamia as gods.

The writer is here affirming the monotheistic world view: the son is not a god, it is a creation of the one God.

The moon is not a goddess: it is a creation of the one God.

The sky is not a god, nor is the earth. Both are creations of the one God.

http://www3.northern.edu/marmorsa/histor y121.htm

6

GENESIS

Note also the delineation of creative days. Here too is a challenge to polytheistic practice.

Most ancient societies associated each day of the week with one of the seven “planets” (the sun, moon, and five visible planets), and associated those planets with particular gods.

This is still reflected in the names we give the days of the week!

The writer of Genesis is insisting that this is wrong: we should not honor the sun god on Sunday, the moon good on Monday, etc.

Note also that the writer talks about the importance of a day of rest: here, the 7 th day (Saturday), but idea of such a day of rest is reflected not only in the Jewish Saturday Sabbath, but the Christian

Sunday (Lord’s Day) Sabbath, and the Moslem Friday Sabbath.

http://www3.northern.edu/marmorsa/histor y121.htm

7

GENESIS

Note also the affirmation of the goodness of all created things—including human beings who are made in the image of God.

Particularly important is the idea that *women*, not just men, are created in God’s image—an idea we take for granted, but certainly not universal in the ancient world.

And note that there is a particular high view of mankind: we are not just the dust of the ground, but we have the spirit of God as well.

http://www3.northern.edu/marmorsa/histor y121.htm

8

GENESIS

So, if God created all things good, what happened?

The writer of Genesis insists that the evils of this world come through human choices.

The temptation for Adam and Even is that they would “know” good and evil.

What this means is that they would *decide* what’s good and evil for themselves.

The writer suggests that this very plausible idea (everyone chooses for themselves what’s good and evil according to their own standards) is potentially very destructive.

Adam and Eve see no reason not to eat: but they soon find unexpected consequences of their actions.

http://www3.northern.edu/marmorsa/histor y121.htm

9

GENESIS

1. Hardship, death, a broken relationship with nature, and a broken relationship with God

2. A distorted relationship between men and women. “Your desire will be to your husband” means what *you* want, he will have. Men will have power over women and women won't like it.

3. Eve is told god would greatly multiply her sorrow “in her conception.” Most translators take this to mean the pains of childbirth, but I don't think this is right.

The sorrow is not so much in child-bearing (which would be a different Hebrew word) but in the *children* she conceives--childrearing won't be nearly as happy as it should be (cf. Cain and Abel). http://www3.northern.edu/marmorsa/histor y121.htm

10

GENESIS

Genesis also suggests a remedy for the evils of the world around us: obedience.

This is particularly clear through the contrast of Abraham and

Adam.

Adam disobeys in a simple thing, while Abraham obeys in progressively more difficult things--leaving his native country and his goods, sacrificing Isaac.

Christians, of course, see in this foreshadowing of their own teaching on faith--faith as obedience to God no matter what.

One sees also the influence of Genesis in the many familiar stories in the book, stories of Noah, Sarah, Jacob and Esau, etc.

http://www3.northern.edu/marmorsa/histor y121.htm

11

DEUTERONOMY

“Deuteronomy” is Greek for “second law” or, rather, the repetition of the law.

It is actually the fifth book of the Torah.

It is set toward the end of Moses’ life.

Moses has gathered his people together, given them a synopsis of their history, and then goes through the law again, at the end asking for the people of Israel to commit themselves to following the law and renewing their covenant with God.

http://www3.northern.edu/marmorsa/histor y121.htm

12

DEUTERONOMY

Among the laws repeated are the Ten Commandments, originally given in Exodus 20.

These commandments are an excellent example of Tanak influence.

While the laws of Hammurabi were lost for 2000 years, these laws were remembered, and used to be posted on most classroom walls in America and learned by heart by many/most people.

Unlike Mesopotamian laws (and laws later in Deuteronomy) there are no specific penalties attached—possibly indicating that these laws are universal principles meant for all socities.

http://www3.northern.edu/marmorsa/histor y121.htm

13

DEUTERONOMY

Also especially important in Deuteronomy are a couple of verses in Deuteronomy 6, verses Jews call the Shema, “Here, O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is one.

And thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart and all thy soul, and all the strength, and all they might.”

Jews (including Jesus) regard this as the greatest commandment.

http://www3.northern.edu/marmorsa/histor y121.htm

14

ISAIAH

The book of Isaiah is part of the Neviim, the Prophets, and it too shows the influence of the Tanak.

Isaiah lived in a very troubled time in the history of his people.

When he began his mission, the Northern kingdom of Israel was just about to be destroyed by Assyria.

The southern kingdom, Judah, was in trouble as well.

Another problem was social and economic.

A change in agriculture (moving from grain crops to olives and grapes for oil and wine for export) meant a great increase in trade, and wealthy landowners and tradesmen were doing quite well.

But small farmers were going into debt and losing their lands—and often their freedom. Isaiah talks of the poor being sold for the price of a pair of shoes: small debts one couldn’t pay often meant slavery.

http://www3.northern.edu/marmorsa/histor y121.htm

15

ISAIAH

Isaiah takes the problems his people face and addresses them very differently than would the religious leaders of other nations.

The general rule when trying to ensure societal success was sacrifice.

Religious rituals were the key to getting the gods on your side.

Isaiah says no. God doesn’t care about the rituals: He cares how we treat one another, and, especially, how we treat widows and orphans—those who can’t protect themselves.

Much concern about social justice even in today’s society goes back to Isaiah and the propets.

http://www3.northern.edu/marmorsa/histor y121.htm

16

ISAIAH

Isaiah is also important because of his affirmation of the idea that, even in the bleakest of circumstances, there is hope.

Isaiah is a *very* difficult book because it alternates bleak passages with joyful ones.

This is deliberate: Isaiah can see the awful things that are going to happen to his people, but he promises also future hope.

Passages like Isaiah 9 talk of a messiah, one anointed by God to deliver his people.

Christians take such passages as references to Jesus, especially the passage in Isaiah 53 which looks like a prediction of the sacrificial death of Christ.

Jews, of course, don’t agree with this interpretation, but note that the very idea at the heart of Christianity (a messiah who would pay for the sins of the world) comes out of

Isaiah http://www3.northern.edu/marmorsa/histor y121.htm

17

PSALMS

In Jewish reckoning, the Psalms are part of the Kituviim, the writings. What we have are 150 songs, prayers, prophecies, historical summaries—essentially the Jewish hymnal.

The Psalms are likewise used by Christians in worship: the first book published in America was the Bay Psalm Book, English translations of these Psalms.

Worship affects people’s hearts deeply, and the Psalms shows Tanak influence, not just on how we think about things, but on how we feel about things. The 23 rd Psalm, for instance, is one that many turn to for comfort in the face of death.

Within the last hundred years, we have rediscovered many of the songs from Ancient Egypt: beautiful songs. But the Hebrew Psalms didn’t have to be rediscovered: these songs have been in constant use since the time they were written http://www3.northern.edu/marmorsa/histor y121.htm

18

DANIEL

Daniel is regarded by the Jews as part of the writings, and by

Christians as part of the prophets.

Daniel deals with a very important question, the problem of evil. Why is there evil and suffering in world?

Didn't Genesis already address this? Yes, but the answer in

Genesis is only partial.

Genesis says people suffer because they do something wrong.

Often enough, this is true. Someone downs a bunch of beers, gets in a car, shoots off at 80 miles, and ends up in an accident that paralyzes them for life. http://www3.northern.edu/marmorsa/histor y121.htm

19

DANIEL

We wish it was always true that people only suffer when they do something wrong.

But, unfortunately, it just isn't. Perfectly innocent people suffer.

The guy that downs the beers walks away without a scratch, but wipes out a family of five in a station wagon.

Good people suffer—sometimes more than bad people. This is central question that concerns author of Daniel: why do bad things happen to good people?

This is a vital question, and, unless it can be answered, monotheism has very little chance.

How can one believe in a good, loving, all-powerful God when such horrible things happen to good people in this world? Daniel suggests an answer. http://www3.northern.edu/marmorsa/histor y121.htm

20

DANIEL

The beginning of the books of Daniel is absolutely shocking.

The Chaldaeans, the most corrupt of ancient peoples, conquer God’s people, the Jews.

The destroy Jerusalem. They destroy the temple. The do horrible things to their captives

(remember the kind of things they Assyrians did).

Daniel and his friends have lost everything. They’ve been castrated, made into eunuchs.

They’ve even lost their names. Each of these men had had a name honoring the God of

Israel.

Daniel = my God is judge, Mishael = who is like God?

Azariah = Jehovah is my strength, Hannaniah = God is gracious.

There names are changed: Belteshazzar honors the Babylonian god Baal,

Abnego honors the Babylonian god Nebo, and

Shadrach honors the god Aku. Mishach = who is like Aku?

For the rest of their lives, these young men will be addressed by a name equivalent (in our terms) to “Satan is strong,” or “Lucifer’s son.” http://www3.northern.edu/marmorsa/histor y121.htm

21

DANIEL

Very bad things have happened to good people! So what do you do in such circumstances?

1. Obey god anyway. Daniel and his friends follow Jewish dietary laws—and are blessed for it.

2. Be patient. The story of Nebuchadnezzar's (lost) dream shows that God can give wisdom no other source can, but it also has the important message that, though cruel and corrupt kings may rule now, in the end, God will establish his own kingdom.

3. Don’t give in. Never give up, never surrender. Note the story of Nebuchadnezzar's image. When threatened with the fiery furnace Daniel’s friends affirm God’s ability to deliver them, but insist that, even if God doesn’t deliver them, they won't bow down.

4. Remember that earthly powers aren’t what they seem. In the story of Belshazzar’s party, Belshazzar mocks God, he and his party friends drinking out of the cups that had been dedicated to the God of Israel. God writes on the wall: Mene, Mene, Tekel, Upharsin.

http://www3.northern.edu/marmorsa/histor y121.htm

22

DANIEL

Daniel interprets: “mina, mina, shekel, half-a-shekel.” Coins commonly used in the ancient world.

In other words, “nickel, dime, quarter” or “two bits, four bits, six bits, a dollar.”

Daniel interprets this as a series of puns, the idea being that

Belshazzar is nothing more than a joke as far as God is concerned.

After Belshazzar’s defeat, the Persians take over, a people far more sympathetic to Hebrews, people who even let the Jews go back and rebuild their temple.

But even here, Daniel runs into some trouble (cf. the story of

Daniel and the lions Den). Even good earthly rulers are not the ultimate answer!

http://www3.northern.edu/marmorsa/histor y121.htm

23

DANIEL

Now all this pretty clear and straightforward. The next section of

Daniel far more difficult, a very complicated series of visions.

What’s happening is that Daniel is searching for an answer to problem of evil.

He fasts and he prays, and gets a series of visions. But these visisions aren’t at all reassuring: mostly are predictions of worse things to come.

But mixed with these, there is a promise of something else, the eventual establishment of a righteous kingdom where everything is done in the way it should be.

But what good does this do for those who live in meantime? Daniel persists, and finally gets the answer in Daniel 12. http://www3.northern.edu/marmorsa/histor y121.htm

24

DANIEL

Daniel is told that there will eventually be time of trouble worse than anything that had come before.

But after that, deliverance. And something more: a resurrection where the righteous would be rewarded and the evil punished.

This a partial answer to the problem of evil.

Certainly in an eternal kingdom, God can make up to you anything that's gone wrong in your life.

Even the worst of things aren't so bad from this perspective: watching your friends and family killed, being taken to a foreign land and castrated isn't going to look quite so bad after a million years of nothing but happiness.

But still, the answer is not quite satisfying. Why did god allow the evil in the first place? http://www3.northern.edu/marmorsa/histor y121.htm

25

DANIEL

Daniel's answer is in Chapter 12 vs. 3 and 10. The righteous will be purified. They that turn many to righteousness shine as the stars forever and ever.

There is something in all the things that he has gone through that makes

Daniel a better person.

Enormous amount of pressure changes a lump of coal into a diamond.

God's answer to Daniel-- I'm turning you into a diamond. I'm turning you into pure gold--into something beautiful that will last forever and ever.

An adequate answer to the problem of evil?

Well, at least as good an answer as anyone has ever been a able to come up with, and an answer that Jews and Christians http://www3.northern.edu/marmorsa/histor y121.htm

26