Word - Anthony D'Amato - Northwestern University

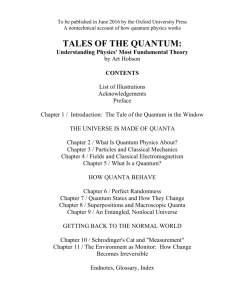

advertisement