Fisc_2010_v5_post

advertisement

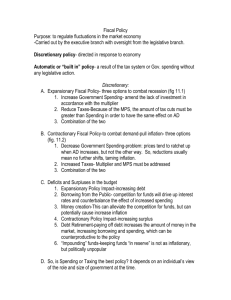

Payne with additions from WN Don’t miss the video of Chicken Little and the financial crisis at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1IUZCyU1S9I 2 The overall federal budget 26 24 Expenditures 22 Deficit 20 18 Revenues 16 14 60 65 70 75 80 85 90 95 00 05 10 3 Debt bathtub Spending Debt (end of year) = Debt (beginning) + deficit Debt (beginning of year) Revenues 4 Debt algebra Basic identity: Debt (end of t) = Debt (beginning of t) + Deficit (t) Stable system when debt-GDP ratio is constant. Define debt-GDP ratio = β Primary surplus = Π = taxes – noninterest spending. Given U.S. parameters, stable β when Π = 0. Algebra of stable debt - GDP ratio. Assume g = nominal GDP growth. Then, equation for change in debt is: D/t iD Then debt-GDP ( = D/Y) ratio is constant when /t 0 D/t / D g iD / D g (i g ) / Y Historically for the U.S., i g, so a stable financial situation implies that the primary deficit must be zero ( 0). Primary surplus ratio Clinton-era surpluses .06 Primary surplus/GDP .04 Recession and stimulus package .02 .00 -.02 -.04 -.06 -.08 60 65 70 75 80 85 90 95 00 05 10 Structural v Actual Budget • Actual budget is actual spending and receipts • Structural budget records spending, taxes, and deficit that would occur if economy at potential output • Important because taxes, spending programs respond to state of economy 7 Structural and Actual Budget .04 .02 .00 -.02 -.04 A substantial part of the deficit is cyclical. -.06 Govt surplus/GDP Cyclically adjusted govt surplus/GDP -.08 -.10 60 65 70 75 80 85 90 95 00 05 10 8 Cyclicality of the federal budget 2 Federal surplus/GDP 0 Unemployment up 1% point → Deficit/GDP up about 1.7%. -2 -4 -6 The recession to date has raised the debt-GDP ratio by 16 percentage points! -8 -10 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Unemployment rate 9 Current projection of debt/GDP 10 Long-term projection of debt/GDP 11 What are the sources of the spending growth? Projected federal spending as % of GDP 14 12 10 8 6 4 Social Security Health Everything else 2 0 2010 2015 2020 2025 2030 2035 2040 CBO, The Long-Term Budget Outlook, June 2010 12 Preliminaries on Government Debt • Fundamental difference between spending on I and spending on C: - Borrowing for spending on I is not a burden unless MPK of government I < MRK of private I (e.g., roads, high-speed rail, education, missiles v. private I). - Problems arise from borrowing for government consumption • Don’t forget the “two faces of saving” - Higher deficits in recessions raise output through AD - Higher deficits (and therefore lower government saving) lowers investment and therefore growth in potential output 13 For the moment, assume full-employment economy. Come back to “dilemma of the deficit” in recessions later. 14 Impact of Deficits on Economy y = f(k) y* y** i = s1f(k) i = s2f(k) (I/Y)* (n+δ)k k k** k* 15 ln K, ln GD ln K ln K’ ln GD’ ln GD time 16 ln Y, ln C ln Y ln Y’ ln (C+G) ln (C+G)’ Note that govt spending first raises (C+G), but then lowers (C+G)’ time 17 What if deficit spending in an open economy? • In open economy: Sp + Sg = I + NX = domestic + foreign investment • Higher deficit reduces domestic and foreign I – I.e., some of decline in savings is in foreign assets • For small open economy, the marginal investment is abroad! – Therefore, no effect on GDP, but has effect on income from abroad – Will show up in NNP not in GDP! (Most macro models get this wrong.) • Large open economy like US: – Somewhere in between small open and closed. – I.e., some decrease in domestic I and some in decrease net foreign assets 18 Initial position r = real interest rate S0 Initial NX surplus r = rw I(r) 0 I, S, NX 19 With higher saving in small open economy r = real interest rate S1 S0 Higher deficit: 1. Lower savings 2. No change I or Y 3. Lower foreign saving 4. Lower GNP, NNP Initial NX surplus r = rw Final NX deficit I(r) 0 I, S, NX 20 American views on the national debt “The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States.” [U.S. Constitution] “A national debt, if it is not excessive, will be to us a national blessing.” [Alexander Hamilton] “It’s a public debt… we owe it to ourselves… therefore, we never have to pay it back.” [F. D. Roosevelt] “There are myths also about our public debt. Borrowing can lead to overextension and collapse – but it can also lead to expansion and strength. There is no single, simple slogan in this field that we can trust.” [J. F. Kennedy, Yale Commencement Address, 1962] “This debt is like a cancer that will truly destroy this country from within if we don't fix it,“ [Erskine Bowles, Nov. 29, 2010] 21 Seven Important Views on the Debt and Deficit 1. In closed economy, lower public saving lowers growth of potential output. - Higher deficit and debt leads to lower saving and capital stock - Leads to lower potential output (we will review the savings experiment) 2. In open economy, deficit leads to lower foreign investment (more foreign debt). This predominates in small open economy. 3. Higher debt forces higher taxes or crowds out other spending 4. Efficiency impacts of higher debt: - Higher debt means higher interest payments - These require taxes, and this has a “dead-weight loss” 5. Debt is irrelevant. Only spending matters (Barro’s Ricardian theory) 6. High debt can lead to financial crisis, higher interest rates, higher deficits, and a death spiral of confidence 7. We should raise the deficit in recessions. 22 4. Taxes and debt for a purely internal debt Assume that we “owe the debt to ourselves” - Many identical people - All get benefits and pay taxes to service debt Suppose that we have program which provides $1 in PV of C; and finances it by $1 of debt. Classical case: - Suppose no change in path of output. - Higher interest payments with present value of $1. - Taxes cause efficiency losses with a dead-weight loss (DWL). - If marginal DWL on taxes is 30%, then have cost of $0.30. - Net value of government program is minus $0.30. 23 The marginal dead weight loss of debt/taxes = incremental DWL of higher taxes P(1+τ2) ~ increase revenues P(1+τ1) DWL P X2 X1 X0 What do Keynesians say about this? Keynesian case: - With multiplier of 1.5, output is 1.5 higher - With tax rate of 0.3, higher net debt is $1 – (0.3 x 1.5) = $0.55 - If marginal DWL on taxes is 30%, then have additional cost of 0.3 x 0.55 = 0.165 - Net is + 1.5 - 0.165 = + 1.335 This indicates the big difference of view of Keynesians and classical economists on deficit spending in recessions. 25 5. Do Deficits Matter? The Ricardian Theory of the Debt 1. Robert Barro (Chicago/Harvard) introduced a theory in which deficits do not affect national saving or output. 2. Chicago view of households: They are "clans" or "dynasties" in which parents have children’s welfare in utility function: Ui = ui (ci, Ui+1) where Ui is utility of generation i and ci is consumption of generation i 3. This implies by substitution: Ui = ui (ci, ui+1(ci+1, Ui+2)) = vi(ci, ci+1, ci+2, ...) which is just like an infinitely lived person! 4. Important result: Barro consumers are like a life-cycle model with infinitely lived agents with perfect foresight: There will be no impact of anticipated taxes (or deficits) on consumption or on aggregate demand, but there is impact of government spending. 5. My take: An interesting theory, but does not hold in empirical studies. 26 6. Debt and financial crises “Political incentives for additional borrowing could change quickly if financial markets began to penalize the United States for failing to put its fiscal house in order. If investors become less certain of full repayment or believe that the country is pursuing an inflationary course that would allow it to repay the debt with devalued dollars, they could begin to charge a “risk premium” on U.S. Treasury securities. That could happen suddenly in a confidence crisis and ensuing financial shock. There is precedent for a financial disruption first contributing to large, chronic deficits and then in some cases contributing to the loss of investor confidence and even to a default on a nation’s debt. [However,] the unique position of the United States—because of its economic dominance and the dominant role of the dollar internationally—make it difficult to extrapolate from the experience of other nations in estimating the risk or timing of a financial crisis arising from failure to address the projected U.S. fiscal imbalance. [National Academy of Sciences panel, Choosing the Nation’s Fiscal Future, 2009] 27 A less nuanced view “When the markets lose confidence in a country, they act swiftly and they act decisively. Look at Greece, look at Portugal, look at Ireland, look at Spain. If they markets lose confidence in this country and we continue to build up these enormous deficits and debt, they will act swiftly and decisively.” 28 Country crises as bank runs Problem with financial crisis is that have an additional risk element, where i risky i riskfree where = risk premium on country debt. New stable debt is / t 0 (i riskfree g ) / Y So again assuming that i g , now primary surplus ( ) must be higher: / Y Problem arises because have an unstable equilibrium where country’s liquid liabilities >> its liquid assets. A higher debt → higher probability of default → higher δ → requires more budget cuts and less likely to pay → higher δ → eventually the country decides to default or restructure. Examples: • Greece β=1.4. If markets put δ=5%, primary surplus ratio must be 7% of GDP. If Greeks start revolting, δ=10%, then required surplus goes to 14% of GDP. So have a good and bad equilibrium like bank runs. 29 Probability of default (from credit default swaps*) 970 373 40 * Interpretation: a “100 basis point” = “1 percent per year” = 1 percent per year implicit probability that the bond will fail or default. Two Views the Great (I): 7. The two faces of of saving andUnraveling the deficit dilemma Soft Landing What is the effect of deficit reduction on the economy? 1. In short run: • Higher savings is contractionary • Mechanism: lower S, lower AD, lower Y (straight Keynesian effect) 2. In long-run, neoclassical growth model • Higher savings leads to higher potential output • Mechanism: higher I, K, Y, w, etc. (through neoclassical growth model) Dilemma of the deficit: Should we raise G today or lower G? 32 Impact of fiscal stimulus AS’ AS Price (P) ? AD’ AD Real output (Y) The dilemma of the deficit Compare (1) a full employment deficit spending program with (2) a balanced budget program This numerical example combines our AS-AD and Solow models: Output ratios for two programs: fiscal stimulus v balanced budget 1.15 1.10 1.05 Notes: 1. Actual output is higher for the entire period 2. Potential output is lower for Keynesian program 1.00 Ratio actual outputs 0.95 Ratio potential outputs 0.90 2010 2015 2020 34 The dilemma of the deficit But have higher debt-GDP ratio for long time Debt-GDP ratios fiscal stimulus v balanced budget 0.90 0.80 0.70 0.60 0.50 0.40 0.30 Debt-GDP FE 0.20 Debt-GDP Balanced budget 0.10 0.00 2010 2015 2020 2025 35 Conclusions on Fiscal Policy • Central impact of fiscal policy is on potential economic growth through impact on national savings rate. • Insolvency and Irish crisis probably not a genuine risk for the US in the near term. • But in recessions, need to remember that country needs less saving, not more saving, in the short run. 36