Fisc_2013_l2_v3_post

advertisement

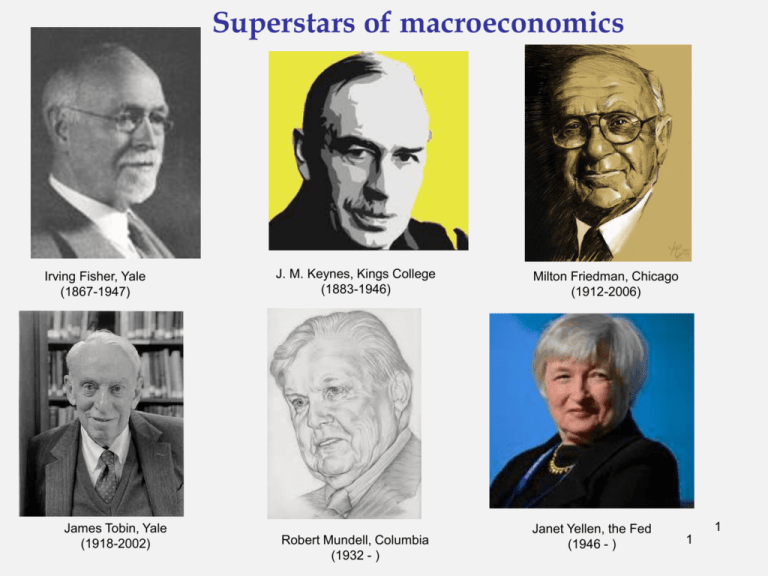

Superstars of macroeconomics Irving Fisher, Yale (1867-1947) James Tobin, Yale (1918-2002) J. M. Keynes, Kings College (1883-1946) Robert Mundell, Columbia (1932 - ) Milton Friedman, Chicago (1912-2006) Janet Yellen, the Fed (1946 - ) 1 1 Debts and Deficits Last time: - Conceptual issues of debts and deficits Deficits and slower growth of potential Y in the closed economy Role of deficit spending in recessions, particularly in the liquidity trap Today: - To raise or lower G in recessions, Europe and US today? The death spiral of debt and default 2 The twoViews faces of and the deficit dilemma Two ofsaving the Great Unraveling (I): Soft Landing What are the effects of deficit reduction on the economy? 1. In short run: • Higher savings is contractionary • Mechanism: higher S, lower AD, lower Y (straight Keynesian effect) 2. In long-run: • Higher savings leads to higher potential output • Mechanism: higher I, K, Y, w, etc. (neoclassical growth model) Dilemma of the deficit: Should we raise G today or lower G? 4 Impact of fiscal stimulus AS’ AS Inflation ? AD’ AD Real output (Y) The dilemma of the deficit To illustrate, I use a little simulation model built from our five equation IS-MP model plus a Solow growth model. 1. Demand for goods and services: yt rtb * Gt t 2. Business real interest rate: rtb it – te t rt t 3. Phillips curve: t te yt t 4. Inflation expectations: 5. Monetary policy: te t 1 i t t r * ( t *) Y yt 6. Potential output: Yt pot At F [ K t , LFt (1 u*)] Then compare (1) a large stimulus program to reach full employment (2) a balanced budget program Use historical data, calibrated model, and “plausible” projections of variables. 6 Stimulus v. balanced budget in 2012 - Balance budget in 4 years (EU style austerity) - Stimulate to reach FE in 3 years (Krugman style superstimulus) - Assume that 50% of public dissaving is offset by private saving. 7 Actual deficits: ½ trillion a year 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018 2020 200 0 Deficit (billions of $) -200 -400 -600 -800 -1,000 -1,200 -1,400 -1,600 Krugman Deficit Balanced Budget Deficit 8 The long-term debt Have higher debt-GDP ratio for long time 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018 2020 2022 2024 2026 90 80 Debt-GDP (% of GDP) 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Krugman Debt-GDP Balanced Budget Debt/GDP 9 But the economy pays the price in high U With fiscal austerity, have long period of stagnation. 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018 2020 14 12 10 Percent - 8 6 4 2 0 Krugman U rate Balanced Budget U rate 10 Lower potential with stimulus Slower growth in potential with stimulus because the debt causes lower capital stock 2004 2009 2014 2019 2024 2029 2034 2039 2044 30,000 28,000 26,000 Potential GDP ($ billions) 24,000 22,000 20,000 18,000 16,000 14,000 12,000 10,000 Krugman Potential GDP Balanced Budget Potential GDP 11 Cumulative Difference in GDP Because of recession, balanced budget doesn’t make it up in a generation, even without discounting. 2004 2009 2014 2019 2024 2029 2034 2039 2044 100% 90% 80% Percent of GDP 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% Cumulative Diff Krugman-BalBud (% GDP) 12 Conclusions on Debt and Deficits • Central long-run impact of fiscal policy is on POTENTIAL output through impact on national savings rate. • But in deep recessions, particularly in liquidity trap, need larger deficits to stimulate ACTUAL output reach full employment. • So policy needs differ in recession and full employment. 13 Economics of External Debts American Econ Review, August 2011. Also see their book, This Time is Different.. Misinterpretation by Deficit Commissioner “When the markets lose confidence in a country, they act swiftly and they act decisively. Look at Greece, look at Portugal, look at Ireland, look at Spain.* If they markets lose confidence in this country and we continue to build up these enormous deficits and debt, they will act swiftly and decisively.” [Erskine Bowles, Chair, President’s Commission] * BTW: This is completely wrong analytically. 17 Defaults and restructuring are endemic • Default: A sovereign default is defined as the failure to meet a principal or interest payment on the due date (or within the specified grace period). • These are often called “restructuring” or “repudiation” but have the same effect. 18 Reinhard and Rogoff, From Financial Crash to Debt Crisis, AER, 2011 Country fiscal position Fiscal deficits plus loss of confidence pushes over the tipping point to where cannot refinance debts Rising risk premium and interest burden REVIEW: Romer debt model Basic ideas: - This is the run on the bank as applied to countries. - Basic idea is that have an instability because of the impact of risk on country interest rates (rd = rw + σ). - Two equilibria: good (full employment) and bad (default) Assumptions: - Government has debt of D and default probability π. - Governments have a random tax revenue, T, with cdf F(T). - Interest: R 1 r (1 r ) (1- ) R(1- ), where r = risk-free rate. R (R R) / - When T < RD, the government defaults REVIEW: Math of Romer model - Investor equilibrium: (R R) / R - Government default occurs when T < RD, which has a cdf (cumulative distribution function): F ( RD ) - We have two equilibrium equations in R and π. π (prob. of default) REVIEW: Three equilibria 1 Investors Government and taxes 0 R R (interest factor) Simplified Romer model - Investor equilibrium that R = (1+rd) determined by prob of default: R R / (1 ) - Assume for simplicity that taxes (T) are known with certainty to be T*. So government default occurs when T < RD: 1, when T < RD 0, when T > RD - We have two equilibrium equations in R and π. 24 π (prob. of default) With adequate revenues, likely to have good equil. 1 Investors Government and taxes 0 R R (interest factor) π (prob. of default) 1 With low revenues, multiple equilibrium with bad outcome Government and taxes 0 R Investors R (interest factor) EZ interest rates Examples of unstable equilibria 2012-10-01 2012-07-01 2012-04-01 2012-01-01 2011-10-01 2011-07-01 2011-04-01 2011-01-01 2010-10-01 2010-07-01 2010-04-01 2010-01-01 2009-10-01 2009-07-01 6 2009-04-01 2009-01-01 2008-10-01 2008-07-01 2008-04-01 2008-01-01 2007-10-01 2007-07-01 2007-04-01 2007-01-01 The unfortunate weak currencies in the EZ Spain and UK had virtually same deficit and fiscal position in 2010. Interest rates on sovereign debt 8 7 UK Spain 5 4 3 2 1 0 What can the EU do? 1. Fiscal austerity, but with great economic cost. 2. Guarantee debts, but this involves north-south transfer. 3. ECB buy bad debt, but moral hazard and hidden transfers. 4. Break up Eurozone, but this has untold economic perils. [See discussion in earlier class.] 30 Does this apply to the US? Country type 1: What is the historical frequency of foreign debt crises for countries with either fixed exchange rates or debts denominated in external currencies a la Greece, Italy, Spain, Argentina, etc.? Answer: average of 14 every year for last two centuries. Country type 2: What is the historical frequency of foreign debt crises for countries with flexible exchange rates and debts denominated in their own currency? E.g., US. Answer: I could not find one. Why? Because country type 2 can print money ($). Problem is inflation or hyperinflation, not debt crisis. 31 Final words You have heard of the “hard sciences.” But macro is a “very hard science.” Why is it so challenging? Listen to the conversation between Keynes and the revolutionary physicist, Max Planck, that took place at high table in King’s College, Cambridge: “Professor Planck, of Berlin, the famous originator of the Quantum Theory, once remarked to me that in early life he had thought of studying economics, but had found it too difficult! “Professor Planck could easily master the whole corpus of mathematical economics in a few days. “But the amalgam of logic and intuition and the wide knowledge of facts which is required for economic interpretation in its highest form is overwhelmingly difficult.”