Chapter 17

Monopoly

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

Copyright © 2008 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Main Topics

Market power

Monopoly pricing

Welfare effects of monopoly pricing

Distinguishing monopoly from perfect

competition

Nonprice effects of monopoly

Monopsony

Regulation of monopolies

17-2

Market Power

In many situations, competition is not intense

A firm has market power when it can profitably charge

a price that is above its marginal cost

Most firms have some market power, though it may be

very slight

Depends on whether their competitors’ products are close

substitutes

Two market structures in which firms have market

power:

A monopoly market has a single seller

An oligopoly market has a few, but not many, producers

Determining what is and is not a monopoly market can

be trickier than simple definitions might suggest

17-3

How Do Firms Become

Monopolists?

Firms get to be monopolists in various ways:

Government grants a monopoly position to a firm

(cable TV companies in local communities, drug

patents)

Economies of scale (concrete supply in a small

town)

Being first to produce a new product (iPod)

Owning all of an essential input (De Beers diamond

producer)

Many of these ways of initially capturing market

power tend to erode over time

17-4

Figure 17.1: Scale Economies

and Monopoly

Monopolist can make

a profit because AC

lies below the

demand curve at

some quantities

Two firms cannot

make positive profits

AC lies above Dhalf for

all quantities

17-5

Monopoly Pricing

Monopolist will choose the price that maximizes its

profit, given the demand for its product

Whenever the firm’s profit-maximizing sales quantity is

positive, marginal revenue equals marginal cost at that sales

quantity

Marginal cost curve applies as usual

Need to examine the shape of the marginal revenue

curve

Recall that a firm’s marginal revenue curve captures

the additional revenue it gets from the marginal units it

sells, measured on a per-unit basis

17-6

Marginal Revenue for a

Monopolist

An increase in sales quantity (DQ) changes revenue in two ways

Firm sells DQ additional units of output, each at a price of P(Q),

the output expansion effect

Firm also has to lower price as dictated by the demand curve;

reduces revenue earned from the original (Q-DQ) units of output,

the price reduction effect

The overall effect on marginal revenue is:

DP

Q

MR PQ

DQ

So the price reduction effect makes the monopolist’s marginal

revenue less than price

17-7

Figure 17.2: Marginal Revenue

and Price

17-8

Sample Problem 1 (17.2):

Suppose that Noah and Naomi have a

monopoly in the garden bench market.

Their weekly demand is D(P) = 500 – 4P.

What is their marginal revenue when they

sell 100 garden benches a week? Graph

their inverse demand and marginal

revenue curves.

Monopoly Profit Maximization

When a monopolist maximizes its profit by selling a

positive amount, its marginal revenue must equal its

marginal cost at that quantity

If marginal revenue exceeded marginal cost the firm would be

better off selling more

If marginal revenue were less than marginal cost the firm would

be better off selling less

Two-step procedure for finding the profit-maximizing

sales quantity

Step 1: Quantity Rule

Identify positive sales quantities at which MR=MC

If more than one, find one with highest profit

Step 2: Shut-Down Rule

Check whether the quantity from Step 1 yields higher profit than

shutting down

17-10

Figure 17.4: Monopoly Profit

Maximization

17-11

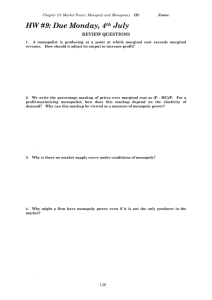

Markup

A monopolist facing a downward sloping demand

curve will set its price above marginal cost

Firm in a perfectly competitive market sets price equal to

marginal cost, meaning that the firm has no market power

Extent to which price exceeds marginal cost is a

measure of monopolist’s market power

A firm’s markup, price-cost margin, or Lerner

index equals the difference between its price and its

marginal cost, as a percentage of its price

P MC

1

d

P

E

17-12

Markup

A monopolist’s markup at its profit-maximizing

price always equals the reciprocal of the

elasticity of demand, times negative one

The less elastic the demand curve, the greater

the firm’s markup over its marginal cost

When demand is less elastic, raising the price

is more attractive because fewer sales are lost

This also implies that demand must be elastic

at the profit-maximizing price

17-13

Sample Problem 2 (17.4):

Suppose KCC has faces an annual

demand function Q = 16,000 – 200P,

where P is the price, in dollars, of a cubic

yard of concrete and Q is the number of

cubic yards sold per year. Its marginal cost

of $20 per cubic yard and an avoidable

fixed cost of $100,000 per year. What is its

profit-maximizing sales quantity and price?

Welfare Effects of

Monopoly Pricing

By charging a price above marginal cost, the

monopolist makes consumers worse off than under

perfect competition

Consumers who buy the product pay more for it

Some who would have bought it under perfect competition will

not buy it at the higher price

Welfare effects of monopoly pricing:

Firm gains

Consumers lose

Deadweight loss incurred

Deadweight loss from monopoly pricing is the amount

by which aggregate surplus falls short of its maximum

possible level, which is attained in a competitive

market

17-15

Figure 17.5: Welfare Effects of

Monopoly Pricing

17-16

Distinguishing Monopoly from

Perfect Competition

Existence of more than one firm in a market

does not guarantee perfect competition

How can we tell whether multiple firms in a

market are behaving like price takers or

colluding and acting like a monopoly?

Easy to answer if we could observe marginal costs

and compare to price

Monopolists and perfectly competitive

industries behave differently in responses to

changes in demand and changes in costs

17-17

Response to Changes in Demand

Monopolist’s profit-maximizing price depends

on elasticity of demand

Price in perfectly competitive market depends

on level of demand

If elasticity of demand changes but level of

demand does not, provides a way to

distinguish between market structures

Can investigate this through data collection

over time and statistical analysis

17-18

Figure 17.7: Response to a

Change in Demand

17-19

Response to Changes in Cost

How do monopolies and perfectly competitive markets

differ in their response to changes in costs?

Consider the case of a marginal cost increase by a

given amount at every level of output

Example: a specific tax, T, on firms

The pass-through rate is the increase in price that

occurs in response to a small increase in marginal

cost, measured per dollar of increase in marginal cost

In a competitive market, the pass-through rate is never

greater than one

The monopolist’s pass-through rate depends on the

shape of the demand curve

Can be greater than one with a constant-elasticity demand

curve

17-20

Nonprice Effects of Monopoly:

Product Quality

Product quality is a decision firms make

Raising a product’s quality increases the consumer’s

willingness to pay

Producing a higher-quality product usually costs more

The firm must decide whether the extra benefit is worth the

extra cost

How does the quality provided by a monopolist

compare to the level that would maximize aggregate

surplus?

If different consumers value quality differently, the

monopolist may not choose to offer the quality that

maximizes aggregate surplus

May over- or under-produce quality

17-21

Product Quality: Car Wash Example

Suppose the only car wash in town is deciding whether to provide

hand washing

Without hand washing the firm maximizes profit by selling 100 washes at

$15 each, profit is $1,000

Hand washing costs $5 more per wash

Consumers whose willingness to pay is above $22 value a car wash

$15 more if done by hand

All other consumers value a hand wash $5 more

With hand washes, firm’s profit-maximizing quantity is 100 washes at

$20 each, with profit of $1,000

Aggregate surplus:

Without hand washes: $1,500

With hand washes: $1,800

Firm is indifferent between providing and not providing the higher

quality product

If cost of hand washing were $5.01, monopolist would choose not to

provide it even though aggregate surplus would be greater with it

17-22

Figure 17.9: Monopolist and

Product Quality

17-23

Sample Problem 3 (17.20):

The only gas station in a small town sells both

regular and premium gasoline. The weekly demand

functions for the two gasolines are:

QReg = 10,000 – 1,000PReg +50PPrem and

QPrem = 350 + 50PReg – 100PPrem

where the quantities are measured in gallons and

prices in dollars per gallon. Are these products

substitutes or complements? If the price of regular

gas is $3.00 per gallon, its marginal cost is $2.95,

and the marginal cost of premium is $3.05, what is

the profit-maximizing price of premium gas?

Nonprice Effects of Monopoly:

Advertising

Spending on advertising is another important decision for many

firms

Because the monopolist’s marginal cost is less than the price,

each additional sale increases its profit

Firms in perfectly competitive markets have no individual incentive

to advertise

Each firm perceives itself as capable of selling as much as its desires

at the market price

Marginal benefit of advertising equals the increase in sales times

the firm’s profit on additional sales

At the profit-maximizing level of advertising, this marginal benefit

must equal the extra dollar expended

For a monopolist, the ratio of the amount spend on advertising to

the firm’s total sales revenue, the advertising-sales ratio, equals

the advertising elasticity divided by the elasticity of demand, times

negative one

17-25

Nonprice Effects of Monopoly:

Investments

Firms can also make investments in an effort to become a

monopolist

Example: cable TV firms lobbying government officials to award them

franchises

If firms compete to become a monopolist, they will spend up to the

full monopoly profit less avoidable fixed costs

If spend on socially wasteful things (e.g., golf outings for local

officials) the loss from monopoly may be larger than deadweight loss

and include all monopoly profit

Rent seeking is socially useless effort devoted to securing a

monopoly position

Welfare effects of monopoly need not always be so bad

Expenditures firms make to gain monopoly positions can be socially

valuable (e.g., R&D spending in the search for patentable drugs)

17-26

Monopsony

Market power isn’t limited to the sellers of a product: it

also can be held by buyers

A monopsony market has a single buyer

Analysis of monopsony parallels the analysis of

monopoly

A monopsonist faces an upward-sloping supply curve

By lowering the quantity he buys, can pay less

Monopsonist can think either in terms of what price to

pay or in terms of how many units to employ

17-27

Marginal Expenditure

A monopsonist’s marginal expenditure, ME, is the

extra cost per marginal unit of an input

Consider a small city in which the hospital is the only

employer of nurses

The hospital’s marginal expenditure has two parts

The input expansion effect: the marginal nurse costs W

Given the upward-sloping supply curve, the hospital must

increase the wage by (DW/DQ) to hire another nurse

Since the hospital must pay Q nurses this higher wage, the

wage increase raises nursing costs by (DW/DQ) Q

So ME is larger than W since the total effect is:

ME W DW / DQQ

17-28

Monopsony Profit Maximization

The monopsonist’s profit-maximizing choice

equates its marginal benefit with its marginal

cost

Maximizes its profit by choosing the quantity at

which its demand and ME curves cross

Result is lower price and quantity than if the

firm was a price taker

Can solve for the equilibrium algebraically by

setting marginal benefit equal to marginal

expenditure and solving for quantity

17-29

Figure 17.10: Monopsony

Profit-maximizing

outcome:

Occurs where

marginal expenditure

curve crosses the

demand curve

Firm hires 200 nurses

Wage is $50,000

Deadweight loss is

red-shaded area

17-30

Welfare Effects of

Monopsony Pricing

Like with monopoly, monopsony price setting

creates deadweight loss

Monopsonist uses too little of the input

Potential net benefits from the input are lost

Deadweight loss is created between the

marginal benefit and market supply curves

See the red-shaded region in Figure 17.10

Can compute the dollar value of the

deadweight loss using algebra

17-31

Sample Problem 4 (17.15):

The Happyland Hospital is a monopsonist

employer of nurses in the small city of Happyland.

The supply function of nurses is S(W) = 0.1W –

100, where W is the nurses’ weekly wage. What is

the hospital’s marginal expenditure, ME? If the

hospital’s marginal benefit is $2,000 per week no

matter how many nurses it hires, what is the profitmaximizing number of nurses for the hospital to

hire? What will the nurses’ wage be? What is the

deadweight loss?

Regulation of Monopolies

Deadweight loss from monopoly pricing provides a

justification for government intervention

Government actions that keep prices closer to marginal

cost can protect consumers and increase economic

efficiency

Intervention can take many forms

Antitrust legislation (see Chapter 19)

Direct regulation of prices

Price regulation not common in U.S. today

More prevalent in the past

Still used for electricity, natural gas, local telephone service

More common in some other countries

17-33

Why Are Some Monopolies

Regulated?

Regulation arises out of political pressure and

economic concern about market dominance

When governments create monopolies they may then

regulate them to deal with the negative consequences

May create a monopoly to ensure that goods are

produced at least cost

A market is a natural monopoly when a good is

produced most economically through a single firm

Average cost falls as quantity increases

Second firm may enter but this would cause costs to rise

Government can designate one firm to be the provider

Institute price regulation to protect consumers

17-34

Figure 17.11: A Natural Monopoly

17-35

First-Best vs. Second-Best Price Regulation

Under regulation, ideally prices will be set at the

competitive price

Price at which demand and supply curves intersect

Aggregate surplus will be maximized

First-best solution to problem of price regulation

Two problems with achieving this lead to second-best

regulation

Regulator may not know the firm’s marginal costs

First-best solution would cause the monopolist to lose

money

If P < AC

Best the regulator can do is set a price that makes

aggregate surplus as large as possible, allow the firm to

break even

Set P = AC

17-36