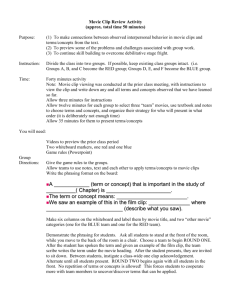

Lecture Powerpoint

advertisement

Movie Clip Lesson Plan Sandra Rutherford Geography and Geology Department Eastern Michigan University Hollywood Films Nature of Science The NSTA/NCATE standards: Nature of Science (2), Issues (4), and Science in the Community (7) want teachers to engage students effectively in studies of the history, philosophy, and practice of science by enabling students to distinguish science from nonscience critically analyzing assertions made in the name of science being prepared to make decisions and take action on contemporary issues of interest to the general society by being informed citizens being prepared to relate science to locally important issues BSCS 5E Instructional Model The Biological Sciences Curriculum Study (BSCS) nonprofit corporation has developed a Learning Cycle Model that allows students to: Engage Explore Explain Elaborate Evaluate Engage The engage part of the BSCS instructional model is key to hooking the students into the unit they are studying There is no longer time in the curriculum to show an entire 90 minute Hollywood film However, Hollywood films offer a perfect opportunity to actively engage students to think about the science behind a film Why use Hollywood Films? The science is often incorrectly depicted for purposes of plot advancement – even bad science can be used to teach critical thought!! It is a waste of time to show the whole film but a 10 minute clip can serve as a springboard to a serious discussion of science Live-action shots are much more memorable than notes on a chalkboard (Lighthart, 2000) – high student interest! Appeals to not only the auditory learner but the visual learner as well (Royce, 2002) What to Look for in Potential Movies Dennis (2002) suggests: Scenes in which the director trusts Mother Nature Scenes with on-screen measurements Good science episodes in all types of films Avoid “oldies but goodies” Viewing time: 10 minutes or less Mother Nature Avoid slow motion scenes, it is better to work with action that is continuous or in “real time” Big climactic action scenes should be avoided because usually the director wants to “take your breath away” so often time slows down, camera angles are changed, gravity drops to one-third its normal value On-Screen Measurements Perhaps the director wants to create suspense so they will show you a digital readout of time or actors are calling out the reading for some important parameter Using the numbers given and knowledge from the classroom, calculations can be made Students are very curious as to how the “stuff” they learn in science is related to the “real stuff” in a movie Good Science in all Types of Films Broaden the video horizons: science can be found in very unexpected places For example the last scene in Ice Age has the iceberg floating above the water not 2/3 below it. “Oldies but Goodies” Stick to movies that are no more than 15 years old Teens are turned off by stars they don’t know, by old-time fashions or machines, and by black-and-white pictures Students will relate to and focus on films of recent vintage Recent films are “certified cool” 10 minutes or less Class time is too precious to give away to a 90 minute Hollywood production that you probably need parental permission for But a well-chosen slice of a movie which complements an activity, discussion, or calculation adds punch to the science concept being addressed However, include the lead-up action to the science “punch line”, they will see the science better when it occurs How can Movie Clips be used in the Classroom? The Class Opener – questions on the overhead for after the movie clip The Group Estimation Problem – calculate something Practice/Reinforcement Activities – the clip can be a “visual word problem’ to create a review of the science “Makin It Reel” Activities – use the clip to handle bad science – ask a question or do an activity Help with “Bad Science” Go to www.nitpickers.com Stick with PG-13 films as often as you can Preservice Teacher’s Assignment In my Earth Science Teaching Methods class at EMU the assignment was to write a lesson plan that uses a Hollywood movie clip An activity to supplement the conceptual question the movie presented was also required Example: Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Arc The students then calculate the mass of the golden idol by measuring the volume of the idol and knowing that the density of gold is 19.2 g/cm3 Example: Waterworld The future, the polar ice caps have melted covering the Earth with water. Those who survive have adapted to a new world. Students could then have an assignment handed out where they actually calculate how high the oceans would rise. Example: Triple X Class Discussion: Can a snow boarder go faster than an avalanche? Can a skier? What is your hypothesis? Do some research? This could relate to other types of mass wasting and their formation Creativity The preservice teachers in my class often have difficulty creatively choosing a movie clip, then finding a demo or activity to accompany it However, it is worth the effort, the excitement that students display is huge! And your administrator will love your creativity! Small List Superman (1978), 117 minutes: Superman flies into the San Andreas Fault to stop an earthquake (Lighthart, 2000) Escape from LA (1996), 2 minutes: Richter magnitude 9.6 earthquake makes an island of Los Angeles (Lighthart, 2000) Waterworld (1997), 80 minutes: Submersible bubble pulled underwater more than 200 meters to “dry land.” there are a lot problems with this, not the least of which is that melting all the glaciers would only raise the sea level by 100 meters. (Lighthart, 2000) The X-Files (1998), opening scene: Primitive humans are walking across glacial terrain in northern Texas 30,000 years ago. (Lighthart, 2000) Fantasia (1940), 38 minutes: 24 minute scene showing the formation and early history of the Earth (up to, but not including, the Cenozoic Era). There are many alternative starting points such as early volcanism (42 minutes) and Ediacaran life (land plants) (47 minutes). (Lighthart, 2000) Volcano (1997), 4 minutes: Description of plate tectonics as floating plates, from which magma can occasionally burst forth at weak points, like Los Angeles. (Lighthart, 2000) Small List Deep Impact (1998), 89 minutes: Discussion of an asteroid hitting the Atlantic Ocean and creating a tsunami. Impact depicted at 103 minutes. (Lighthart, 2000) Joe vs. The Volcano (1990), 91 minutes: Volcano erupts and sinks into the ocean. (Lighthart, 2000) Dante’s Peak (1997): The entire movie can be assigned as an exercise in critical thought. (Lighthart, 2000) Tremors (1990), opening scene, geologically speaking: Seismographs barely register dirt shoveled directly on top of them. (Lighthart, 2000) Jurassic Park (1993), 5 minutes: Opening scene at the “velociraptor” (actually a much-larger Utahraptor excavation, where groundpenetrating radar is used to image a buried skeleton. (Lighthart, 2000) Armageddon (1998): asteroid is the size of Texas but in fact largest known asteroid is just over half the size of Texas. (Royce, 2002) Speed (1994): Bus leap (Dennis, 2002) Six Days, Seven Nights (1998), 1 hour 21 minutes: calculate the initial velocity and maximum height attained by a cannon shell fired straight up (Dennis, 2002) Small List Speed 2: Cruise Control (1997), 1 hour 42 minute: determine the average force exerted by the tropical island in bringing the ocean liner to a stop (Dennis, 2002) Toy Story (1995), 54 minute: 2 segments where Sid the bad kid uses a magnifying glass, Woody uses and misuses a curved mirror, Buzz and a thin lens have a deflating experience (Dennis, 2002) Back to the Future (1985) 30 minutes: DeLorean sports car has a digital speedometer to calculate a simple acceleration calculation (Dennis, 2002) Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937): The wicked queen tries to dislodge a boulder onto the angry dwarfs using a lever; her displacement during free fall can be calculated (Dennis, 2002) The Fugitive (1993): After the opening train wreck, Tommy Lee Jones discusses the fleeing fugitive giving enough information to provide a great review of d-versus-t graphs (Dennis, 2002) Matilda (1996): In the opening sequence, the negligent parents fail to secure the newborn’s car seat and Newton’s first law is clearly demonstrated (Dennis, 2002) Men in Black (1997): Good – alien displacement in free fall can be calculated; bad – the reaction force on Will Smith when he fires the alien weapon (Dennis, 2002) References Daley, Ben (2004) A project-based approach: students describe the physics in movies, The Physics Teacher, v. 42, p41-44. Dennis, Chandler, M., Jr. (2002), Start Using “Hollywood Physics” in Your Classroom!, The Physics Teacher, v. 40, no. 7, p420-424. Dubeck, Leory W. and Tatlow, Rose (1998) Using Star Trek: The Next Generation Television Episodes to Teach Science, Journal of College Science Teaching, v.27, n.5, p319-323. Dubeck, Leory W., Bruce, Matthew H., Schmuckler, Joseph, S., Moshier, Suzanne E., and Boss, Judith, E. (1990) Science Fiction Aids Science Teaching, The Physics Teacher, V. 28, p316-318. Freudenrich, Craig, C. (2000), Sci-fi science, The Science Teacher, v. 67, no. 8, p42-45. Hickam, Homer H., Jr. (2000) A Reflection on Rocket Boys/October Sky in the Science Classroom, Journal of College Science Teaching, V. 29, No. 6, p 399-400. Lighthart, Alyson (2000) Hollywood Geology, Journal of Geoscience Education, v. 48, n.5, p.601. Massenzio, Lynn (2001) X-traordinary Science, Science Scope, v. 24 no. 4, (Jan.), p46-7 Royce, Christine Anne (2002) Lights, camera, and the action of science, Science Scope, V. 25, no. 6, (March), p70-74.