Carcinomas - Wendy Blount, DVM

advertisement

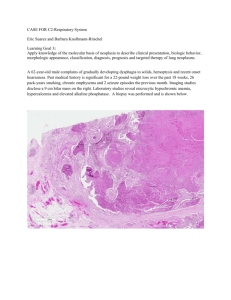

Carcinomas Wendy Blount, DVM Carcinomas • • • • • • Squamous cell carcinoma (canine & feline) Transitional cell carcinoma (canine) Mammary Gland Tumor (canine & feline) Perianal tumor (canine) Anal sac tumors (canine) Thyroid Carcinoma • Meningioma Squamous Cell Carcinoma Feline Squamous Cell carcinoma • Second most common tumor in the cat • Oral SCC behaves differently than skin SCC Canine Squamous Cell Carcinoma • Similar behavior as SCC in cats, but not as common Squamous Cell Carcinoma Feline Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma • Most frequently on the head – Pinnae, nose, eyelids • Caused by sun exposure to light colored skin • Progression over time – Solar dermatitis – crusts and scabs – Actinic dermatitis - plaques – SCC in situ – noninvasive mass – Invasive SCC – ulcerative, invasive mass Squamous Cell Carcinoma Feline Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Solar dermatitis Actinic dermatitis Squamous Cell Carcinoma Feline Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma SCC in situ SCC Squamous Cell Carcinoma Feline Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma • Cytology often not helpful – Very inflammatory • Dx - histopathology • Staging not usually necessary, as metastasis is rare • Tx – early lesions – Surgery, cryosurgery, Strontium radiotherapy, photodynamic therapy – immunomodulatory agent imiquimod (AldaraTM) as a topical cream Squamous Cell Carcinoma Feline Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma • Tx – advanced lesions – Difficult to treat – Removal of the nasal planum is possible, but disfiguring Squamous Cell Carcinoma Feline Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Partial planectomy Pinnectomy and planectomy Squamous Cell Carcinoma Feline Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Untreated for too long Squamous Cell Carcinoma Feline Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma • Most common oral tumor in the cat • Gingiva, tongue/sublingual, tonsil • Much more aggressive than cutaneous SCC • Maxillary tumors can mimic tooth abscess • Surgery often not possible • Radiation sensitive, but high morbidity – mandatory feeding tube Squamous Cell Carcinoma Feline Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma • Chemotherapy not effective • NSAIDs are palliative • Median survival 44 days + NSAIDs • 9% survival at one year • Survival more than a few months even with multimodal therapy is rare (BJ Honeycat) Squamous Cell Carcinoma Feline Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma • Often presents as multiple nail bed tumors • Primary tumor is found on chest x-rays • Always take chest x-rays prior to amputating a possibly neoplastic nail bed in a cat • Animals with systemic neoplasia often do not do well under anesthesia • Amputation is palliative only Squamous Cell Carcinoma Canine Digital Squamous Cell Carcinoma • Nail bed SCC can be primary in the dog • MSA, MCT and SCC are most common digital tumors in the dog • SCC more likely to show bony lysis than others • Toe amputation is often curative • LN aspiration and thoracic radiographs indicated prior to surgery Transitional Cell Carcinoma • Most common bladder tumor in the dog (90%) • Most common symptoms are hematuria and stranguria • Things that increase suspicion – Atypical transitional cells in the urine sediment – Mass in the bladder or urethra on imaging – Thickened urethra on rectal exam (sheltie) – Ruptured urethra on catheterization (chihuahua) Transitional Cell Carcinoma Etiology • Exposure to older topical flea treatments, dips and lawn chemicals (28x) • Possibly cyclophosphamide therapy • Neutered > sexually intact (2.5x) • Scottish terriers 18-20x other dog breeds – Eating vegetables 3x a week is protective • Shelties, Westies, beagles 3-5x other breeds Transitional Cell Carcinoma Dx – histopath • Surgery, cystoscopy, traumatic bladder wash • Percutaneous aspiration can seed tumor cells and should be avoided • Take care to avoid seeding during surgery Transitional Cell Carcinoma Tx • At one time, radiation therapy was recommended, as TCC is highly responsive – But resulting permanent incontinence was common • If at the apex, resection can produce long disease free interval (1-2 years) – (Tess) • Secondary UTI is common – treat PRN • Ureteral stents can restore urine flow • Urethral stents can relieve obstruction if urethral sphincter and continence can be preserved • Prepubic cystostomy tube can relieve obstruction Transitional Cell Carcinoma Tx - NSAIDs • Mainstay of treatment is medical therapy • Not curative, but remission is achieved in 15-20% and stable disease is reached in 75% of dogs • Piroxicam only – median survival 195 days – 0.3 mg/kg PO SID to QOD • Deramaxx only - median survival 323 days – 3 mg/kg PO SID • Previcox similar success • Median survival surgery only is 109 days Transitional Cell Carcinoma Tx - Chemo • Mitoxantrone and piroxicam (see chemo section for details) – 35% remission with minimal toxicity – Median survival 291-350 days • Single agent vinblastine (see MCT notes) – 36% remission – 50% stable disease – Most of these had failed other therapies – Relatively more toxicity than mitoxantrone + piroxicam Transitional Cell Carcinoma Tx - Chemo • Doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide – Median survival 259 days • Metronomic therapy – Chlorambucil 4 mg/m2 PO SID – See Chemotherapy section for monitoring – 29 of 31 dogs had failed prior TCC treatment – 3% partial remission, 67% stable disease, 30% progressive disease – Median survival 221 days Transitional Cell Carcinoma Px • Euthanasia often due to obstruction, metastasis or both • 50% have metastasis at the time of death • Some will invade the sublumbar lymph nodes and then the spinal cord and present as acute posterior paralysis, often with urethral obstruction (1 cat, 2 Rottweilers) Transitional Cell Carcinoma Canine Mammary Gland Tumor • 42% of tumors in all intact female dogs • Rare in dogs less than 5 years old • duration of exposure to ovarian hormones early in life determines the overall mammary cancer risk (Dorn et al, 1968). – 0.5% if OHE prior to the first heat – 8 if OHE prior to the 2nd heat – 26% if OHE after the 2nd heat • tumor risk increases incrementally each year and plateaus around 11–13 (Schneider, 1970) • intact females are more likely to have an anaplastic tumor type, compared to dogs spayed early or late in life, prior to MGT (Ogilvie, 2006) Canine Mammary Gland Tumor The effect of neutering on the risk of mammary tumours in dogs--a systematic review. J Small Anim Pract. June 2012;53(6):314-22. W Beauvais1; J M Cardwell; D C Brodbelt Due to the limited evidence available and the risk of bias in the published results, the evidence that neutering reduces the risk of mammary neoplasia, and the evidence that age at neutering has an effect, are judged to be weak and are not a sound basis for firm recommendations. Canine Mammary Gland Tumor • Review article – not a clinical study at all • Conclusions: – 9/13 were judged to have a high risk of bias, and though they all showed a connection between MGT and failure to spay, they were not considered as evidence. – The remaining four were classified as having a moderate risk of bias. • One study found an association between neutering and a reduced risk of mammary tumors. • Two studies found no evidence of an association. • One reported to have "some protective effect" of neutering on the risk of mammary tumors. Canine Mammary Gland Tumor BMJ. 2003 Dec 20;327(7429):1459-61. Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Smith GC1, Pell JP. OBJECTIVES: To determine whether parachutes are effective in preventing major trauma related to gravitational challenge. DESIGN: Systematic review of randomised controlled trials. RESULTS: We were unable to identify any randomised controlled trials of parachute intervention. CONCLUSIONS: As with many interventions intended to prevent ill health, the effectiveness of parachutes has not been subjected to rigorous evaluation by using randomised controlled trials. Advocates of evidence based medicine have criticised the adoption of interventions evaluated by using only observational data. We think that everyone might benefit if the most radical protagonists of evidence based medicine organised and participated in a double blind, randomised, placebo controlled, crossover trial of the parachute. Canine Mammary Gland Tumor • 70% have more than one tumor at the time of diagnosis • Mammary gland tumors can be epithelial, myoepithelial, mesenchymal or mixed • Complex MGT – epithelial and myoepithelial • Mixed MGT – epithelial and mesenchymal Canine Mammary Gland Tumor MGT Stages • Stage I – less than <3cm and localized • Stage II – 3-5 cm and localized • Stage III - >5cm and localized • Stage IV – any size, metastasis to lymph node • Stage V – any size, distant metastasis Canine Mammary Gland Tumor MGT Staging • CBC – check for evidence of infection • Profile – hypercalcemia • Aspirate draining lymph node • Thoracic radiographs – 3 views • Abdominal US Canine Mammary Gland Tumor MGT Staging • CBC – check for evidence of infection • Profile – hypercalcemia • Aspirate draining lymph node • Thoracic radiographs – 3 views • Abdominal US Canine Mammary Gland Tumor Surgery • As with all masses removed, label margins so they can be read out – Describe the location of the lesion – Mark one end of one direction (e.g., cranial or caudal) with one type suture – Mark one end of the plane 90O to above with another type suture, if necessary – Don’t forget to describe your labeling on the submission form Canine Mammary Gland Tumor Surgery – OHE? • The majority of MGT of epithelial origin express estrogen receptors, suggesting that reproductive hormones may play a role in the pathogenesis • 755 days median survival - dogs spayed at or within 2 years before MGT surgery • 286 days median survival – dogs not spayed at MGT surgery • 301 days median survival – dogs spayed more than 2 years prior to MGT surgery • It’s rare for MGT to develop more than 2 years after OHE Canine Mammary Gland Tumor Prognosis • 50-60% of mammary gland tumors are benign • 98% of tumors <1 cm are benign • 50% of tumors >3cm are malignant • Malignant tumors develop from benign masses • Early removal is usually curative Canine Mammary Gland Tumor Inflammatory Mammary Carcinoma • Acute onset of painful, extensive swelling of the mammary glands • Fine needle aspiration with a 25g needle can drip blood for days (DIC) • Rapidly progressive • Grave prognosis Perianal Tumors • “aka” hepatoid tumor • Most common in older intact male dogs – And females with testosterone producing adrenal tumors • Tumor site – perineum > tail, abdomen • Most often found without symptoms • Tenesmus can be caused by the lesion or submandibular lymphadenopathy (palpable rectally) • 60-80% benign • Those that are malignant often behave as anal sac tumors Perianal Tumors • Staging prior to surgery – Abdominal rads and/or sonography to evaluate sublumbar lymph nodes • Large tumors >2cm and single tumors should be removed • If multiple small tumors or coalescing tumors, castrate first (if male) – Remove any tumors that do not resolve in 2-4 weeks • Unless males are castrated, new tumors will likely arise Anal Sac Carcinoma • Highly malignant – Locally invasive AND distant metastases • 90% develop hypercalcemia – 25-50% are hypercalcemic at diagnosis • 50-94% have lymph node metastasis at the time of diagnosis Anal Sac Carcinoma Presentation • Found on anal sac expression • Dyschezia, tenesmus, ribbon-like stools • Attention to the perineum, scooting • Perianal bleeding • PU-PD (hypercalcemia) • Hind limb weakness or posterior paralysis • May be bilateral – check the other side Anal Sac Carcinoma Staging • Profile – hypercalcemia, azotemia • Abdominal rads and/or sonography – Sonography more sensitive than rectal palpation or rads for finding enlarged sublumbar LN • Thoracic radiographs – 3 views • Aspirate popliteal and inguinal lymph nodes – Sublumbar if large enough and you are comfortable doing this with ultrasound guidance Anal Sac Carcinoma Median Survival – no treatment • 7-9 months – masses larger than 3cm – Dogs with hypercalcemia and/or pulmonary metastasis • 18-19 months – Masses smaller than 3cm – Dogs with normocalcemia and no lung mets Anal Sac Carcinoma Median Survival • Surgery only – 90% survival at 6 months (hypercalcemia often goes into remission, even if incomplete excision) – 65% survival at one year – 29% survival at 2 years – 20% temporary fecal incontinence, some permanent – Wound infection and sepsis can occur – 30% perioperative fatality when sublumbar lymph nodes are removed Anal Sac Carcinoma Median Survival • Multi-modal therapy – surgery, radiation of nodes, doxorubicin/carboplatin – – – – 18-26 months median survival 86% survival at 6 months (similar to surgery alone) 69% survival at one year (same as surgery alone) 36% survival at 2 years (maybe more than surgery alone – 29%) – 14% survival at 3 years • Median survival 22 months with radiation alone – 15% rectal structure Thyroid Carcinoma - Dog • 3-4% of tumors in dogs • 90% are malignant • Boxers, Golden Retrievers and Beagles are at increased risk • Most common presentation is ventral cervical mass – Change in bark or breathing – Cough – Occasionally swelling or regurgitation • Hyperthyroidism is rare Thyroid Carcinoma - Dog Diagnosis • Cytology – Vascular – may get blood only – often confirm endocrine origin, but it can be difficult to confirm malignancy – US guidance can target a solid spot for better results • Incisional biopsy can result in massive hemorrhage – not recommended • US can confirm mass is of thyroid origin Thyroid Carcinoma - Dog Staging • Ultrasound – assess lymph nodes and local invasion • 3 view thorax Thyroid Carcinoma - Dog Treatment • Surgery – If freely moveable, surgery can result in a long disease free interval – If invasive, surgery can be difficult • Hemorrhage • Damage to recurrent laryngeal nerves (LP) or carotid aa. • Hypocalcemia if all parathyroids damaged or removed Thyroid Carcinoma - Dog Treatment • External Beam Radiation – For unresectable masses • 80% stable disease at 1 year, 72% at 3 years – For residual disease after surgery • Chemotherapy – Single agent carboplatin or mitoxantrone – Or alternate – Every 3 weeks, 4-6 treatments – Outcome is unknown Thyroid Carcinoma - Cat • Most present with hyperthyroidism • Diagnosis made by thyroid nuclear scan – Or histopath after thyroidectomy – Cytology may be diagnostic • Treatment – Higher dose of I131 – may need to be repeated – Surgery if no evidence of metastasis on nuclear scan • Chemotherapy remains unexplored Meningioma • Most common brain tumor in geriatric dogs and cats • Dolichocephalic breeds predisposed • 10% of non-lymphoma neoplasias in cats are meningiomas • Multiple meningiomas are not uncommon in cats • Despite being “not malignant,” usually eventually result in death if not removed Meningioma Clinical Signs • Subtle changes in behavior over time – Patients adapts to gradual increase in intracranial pressure • Acute onset of severe neurologic signs not unusual – Cerebral signs most common – Cluster seizures, changes in behavior – Contralateral blindness, ipsilateral circling, looking to that side, pacing – Stupor, head pressing, getting stuck in corners – CP deficits worse in the rear, UMN ataxia Meningioma Clinical Signs • Cranial nerve signs if in the brain stem • Spinal reflex deficits if in the spinal cord – LMN 2 dermatomes caudal to the lesion – UMN below the lesion • Remember cats can have more than one Meningioma Diagnosis • Radiographs are rarely helpful – Occasionally the tumor is mineralized • CSF tap rules out infectious and inflammatory diseases – – – – – – Increased CSF pressure can result in herniation Hyperventilate with 10 breaths prior to stick Give mannitol if high CSF pressure is suspected Pacing, altered consciousness, dysphoria Increased protein, increased mononuclear cells Unusal to see neoplastic cells on sediment Meningioma Diagnosis • MRI gives more information than CT • Contrast may be required • Isolated meningeal tumors presumed to be meningiomas until histopath says otherwise • Biopsy prior to surgery not generally recommended Meningioma Treatment • Surgery often curative – But expensive – Frontal lobe tumors do well – Brain stem surgeries carry high morbidity • Radiation without surgery can give long term palliation • Palliative Medications – Glucocorticoids – anticonvulsants Carcinomas Client Handouts • Squamous Cell Carcinoma • Transitional Cell Carcinoma • Mammary Gland Tumor – Canine • Mammary Gland Tumor – Feline • Thyroid Carcinoma • Meningioma Acknowledgements • Jane M. Dobson, MA, BVetMed, DVetMed, DECVIMCA&Onc, MRCVS Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK • Deborah W. Knapp, DVM, DACVIM (Oncology) Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA • Karin Ulrikke Sorenmo, DVM, DACVIM, DECVIM-CA (Oncology) Veterinary Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA, USA Acknowledgements • Erik Teske, DVM, PhD, Dip ECVIM-CA Clinical Sciences, Companion Animals Utrecht University, THE NETHERLANDS • Katherine Skorupski, DVM, DACVIM (Oncology) Assistant Professor of Clinical Medical Oncology University of California, Davis • Greg Ogilvie, DVM, DACVIM (Oncology) Director, Angel Care Cancer Center, California Acknowledgements • Laura Blackwood, BVMS (Hons), PhD, MVM, CertVR, DECVIM-CA (Oncology), MRCVS, RCVS Small Animal Teaching Hospital, University of Liverpool, Leahurst, Neston, UK • Richard A. LeCouteur, BVSc, PhD, Diplomate ACVIM (Neurology), DECVN University of California Davis, California, USA