Companies and Securities Law - Carpe Diem

advertisement

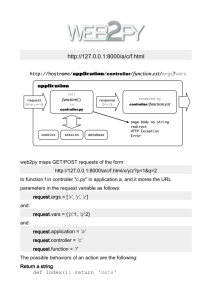

LAWS11064 Torts B Module 3 – Negligence: Standard of Care & Breach of Duty Lecture Outline • Standard of Care Part One • Reasonable person • Characteristics of the Def • Characteristics of the Pl • Breach of Duty Part Two • Reasonable person’s response to foreseeable, not insignificant risk. Objectives At the end of this module you should be able to: • • • • • • Understand and explain how the general standard of care at common law is calculated and applied; Understand the degree to which it is objective, as opposed to subjective; Understand how the issue of breach of duty is determined at common law and appreciate the variety of factors that are weighed up to help determine fault; Explain the general requirements of the Civil Liability Act 2003 in relation to standard and breach of duty; Explain the specific requirements of the Civil Liability Act in relation to standard and breach of duty, by particular classes of defendant, and in particular classes of ‘risky’ behaviour; and Apply the common law and legislative principles to specific fact scenarios to determine the standard of care and breach questions. Negligence Duty of Care (last week) Breach (this week) Does the Def owe Damage (next week) a duty of care to Has there been a breach of the Pl? that duty of care by the Def? Has the breach of duty 1. What is the standard of caused compensable care? loss or damage to the 2. Has there been a breach Pl? of that standard on the facts? Breach & Standard: Reasonable Care • General principle set out in s. 9 CLA (Qld): “what would RP do in response to Reasonably Foreseeable Risk of Injury” • Standard is that of hypothetical “reasonable person” (“RP”). Standard is a question of law. – Objective rather than subjective: how should Def have behaved in the particular circumstances? • Breach of duty is a question of fact. – Has Def met required standard of care in particular circumstances of case? Have they taken reasonable care? Careful behaviour = reasonableness, not necessarily the elimination of risk altogether. The “reasonable person” “negligence is the omission to do something which a reasonable man, guided upon those considerations which ordinarily regulate human affairs would do, or doing something which a prudent and reasonable man would not do”. (Blyth v Proprietors of the Birmingham Waterworks [1856] 1 Ex 781 per Alderson B) “Man on the Clapham Omnibus” (Hall v Brooklands Auto-Racing Club [1933] 1 KB 205 per Greer LJ) “hypothetical person on a hypothetical Bondi tram” (Papatonakis v Australian Telecommunications Commission (1985), 156 CLR 7 per Deane J “ordinary prudence and foresight”: reflected in s.9(1)(c) CLA (Qld). The reasonable person does not have “the prophetic vision of a clairvoyant” (Hawkins v Coulsdon & Purley UDC [1954] 1 QB 319, per Romer LJ at 341). Def’s Characteristics: Skill Starting point: same SoC owed by all people Lack of skill/experience no defence: Imbree v McNeilly [2008] HCA 40 Whether skill alters SOC depends on skill Def holds themselves out to have. • Even if Def acted to ‘best of their own judgment’ or if ‘best’ was below that of reasonable person: Vaughan v Menlove (1837) 3 Bing NC 468; Nettleship v Weston [1971] 2 QB 691. • For Dr’s see Wilsher v Essex AHA [1986] QB 730: “the law requires the trainee or learner to be judged by the same standard as his more experienced colleagues”, per Glidewell LJ • If non-skilled: • Eg. Wells v Cooper [1958] 2 QB 265: “reasonably competent carpenter doing the work in question… he was doing his best to make the handle secure and believed he had done so”, per Jenkins LJ. • Eg. Philips v William Whiteley (1938) 1 All ER 566: Pl’s ear became infected after piercing. Jeweller not liable: took all reasonable precautions a jeweller could take; cannot expect to conform to standards of surgeon. • If Pl holds self out as expert, will be held to expert SoC. • Unskilled Pl undertaking task requiring specialist skill = possible Neg.: eg. Papatonakis v Aust Telecommunications Commission (1985) 156 CLR 7 (telephone linesman died repairing cable installed by unskilled householder) Def’s characteristics: Professionals Specialist/Professional Skill at Common Law CLA and Duty of Professionals • Pl with special skill or knowledge expected to attain standard of a reasonable person with that skill /knowledge. eg. Wilsher v Essex. eg. normally skilful and careful medical practitioner: Mahon v Osborne [1939] 2 KB 14. Specialists will owe standard of persons practising in that speciality: Rogers v Whitaker. • Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee [1957] rejected by HC in Rogers v Whitaker in medical cases concerning duty to warn of risks. • SOC now embodied in s 22 • Reflects Bolam, but extends to all professionals “Professional” = person practising a profession: s. 20 “professional activity” discussed in Prestia v Aknar (1996) 40 NSWLR 165 at 186. Peer professional opinion cannot be relied on if Ct considers it irrational or contrary to written law: s. 22(2) (reflective of judgment in Bolitho v City and Hackney Health Authority [1997] 4 All ER 771). S. 22 does not apply to liability in connection with cases concerning warnings, advice or other information given (or failed to be given) by professionals in relation to the risk of harm. But see s. 21 which applies to Doctors. Def’s characteristics: Medical Professionals • For Medical Professionals: – Diagnosis and treatment is judged against standard of professional set by s 22 CLA – For advice and warnings, special standard applies to doctors to warn of risks as set by s 21(1) CLA. Doctors must give: • Information that a reasonable person in the patient’s position would, in the circumstances, require to enable the person to make a reasonably informed decision about whether to undergo the treatment or follow the advice; • Information that the doctor knows or ought to reasonably to know the patient wants to be given before making the decision about whether to undergo the treatment or follow the advice. See Rogers v Whitaker; and Wallace v Kam (2013) 250 CLR 375 Def’s characteristics: Age & Disability – McHale v Watson [1966] 115 CLR 199: it is no defence to show that he is abnormally slow-witted, quick-tempered, absent-minded or inexperienced (as for adult), but it will be a defence to show that he was acting as normal for his stage of development • Canadian case: Ryan v Hickson [1974] 55 DLR 3d 196: children engaged in adult activities held to adult standard of care. See also Aus case Tucker v Tucker [1956] SASR 297. – Objective or subjective? : “a limitation upon the capacity for foresight or prudence, not as being person to himself, but as being characteristic of humanity at his stage of development and in that sense normal”, per Kitto J. Disability is disregarded Eg. Mentally ill drivers: Adamson v Motor Vehicle Insurance Trust (1957) 58 WALR 56. Mental disability should be ignored as the reasonable person is never insane. See also Carrier v Bonham [2002] 1 Qd R 474 Are Pl’s characteristics relevant? - If the Def knew or ought reasonably to have known that the Pl or the class of persons to which the Pl belongs, was particularly susceptible to injury, this susceptibility will influence the standard of care. - Eg. Paris v Stepney Borough Council (1951) AC 367 (extra precautions required to prevent employee suffering injury to good eye). • Cotton v Commissioner for Road Transport and Tramways (1942) 43 SR (NSW) 66 (where driver sees pedestrian incapable of exercising normal standards, special precautions should be taken). • See also s.46 CLA: “the fact a person is or may be intoxicated does not of itself increase or otherwise affect the SoC owed to that person. Standard dependent upon circumstances • In emergency, may be reasonable to take risks that would not otherwise be reasonable. Watt v Hertfordshire CC [1954] 1 WLR 835, Def’s employee injured by unsecured jack; no time to obtain better vehicle before going to rescue woman trapped under heavy lorry. No liability by Def. Cf Ward v London County Council [1938] 1 All ER 341 (driver of fire engine that ran red light colliding with PL was negligent) – Medical emergencies now protected by CLA (and good samaritan legislation in other jurisdictions – we discuss in more detail in week 7): ss. 26 and 27. See also, Pt 5 of the Law Reform Act which provides protection for medical practitioners and nurses. ‘Person in distress’ – see s. 25. • Sporting situations: Rootes v Shelton (1967) 116 CLR 383; law clarified by Woods v Multi-Sport Holdings Pty Ltd (2002) 208 CLR 460. UK case: Vowles v Evans [2003] 1 WLR 1607, rugby player sued referee for allowing game to get out of hand. Re-cap of Standard of Care 1. Same SoC owed by all people Objective test: Reasonable SoC to be taken by a reasonable person in the position of the Def. 2. Objective test may be altered due to: – Age – Specialist skill – Situation (eg. technical knowledge, emergency, knowledge of Pl susceptibility) SoC can be addressed under s.9(1)(c) Part 2: Breach of standard • See s 9 of the CLA 2003 (Qld): 1. (a) Was the risk foreseeable? (b) Was the risk not insignificant? (c) Would a reasonable person in the position of the Def have taken the precautions? • Essentially a restatement of law in Wyong Shire Council v Shirt (1980) 146 CLR 40. 1. Foreseeable Risk: – Def must know or ought to know of the risk: eg. Tame v NSW; Annetts v Aust Stations (2002) 211 CLR 317. – “Consequence of the same general character”: Doubleday v Kelly [2005] NSWCA 151 Breach: not insignificant • • • • • Pre-CLA, in Wyong Shire Council v Shirt – the test for determining if the risk of injury was reasonably foreseeable was that it be ‘not far-fetched or fanciful’ (drawn form Bolton v Stone). Ipp Report recommended this be substituted with ‘not insignificant’. Few decisions have considered the application of this requirement. In Drinkwater v Howarth [2006] NSWCA 222, per Hodgson J, there is no difference in result by applying ‘not insignificant’ or Shirt test. But see Peter Steven Benic v NSW [2010] NSWSC 1039 (from para 93). In Romeo v Conservation Commission, Hayne J commented: ‘the fact that an accident has happened and injury has been sustained will often be the most eloquent demonstration that the possibility of its occurrence was not far-fetched or fanciful’ (at 165). In NSW v Fahy (2007) 232 CLR 486, Callinan and Heydon JJ recommended the relevant test for ‘not insignificant’ be a risk that ‘is significant enough in a practical sense (at [226]). See Ipp Report, para 7.15. Breach: Reasonable response to risk “Shirt” formula: Wyong Shire Council v Shirt (1980) 146 CLR 40 “the magnitude of the risk and the degree of the probability of its occurrence, along with the expense, difficulty and inconvenience of taking alleviating action and any other conflicting responsibilities the Def may have” (per Mason J at 47). s 9(2) CLA: • • • • Probability: probability of someone being injured by the Def’s activity Severity: the severity of the injuries suffered by the Pl Burden of Practical alternatives: the availability and burden of practical alternatives open to the Def Justifiability: the type of industry or activity that the Def is involved in may carry inherent risks/dangers or social utility. Cost of eliminating risk: expressed in United States v Carroll Towing Co [1947] 159 F 2d 169 as the “Learned Hand” formula. 3 variables: Probability that harm will result to Pl from Def’s action [P]; Gravity of loss or harm [L]; Cost or burden of preventing it [B]. Breach occurs where cost to Def of taking precautions is outweighed by magnitude of risk and gravity of possible harm to Pl; or B<PL s 9(2): Probability of injury Refers to probability or foreseeability of the risk eventuating. • Eg. Bolton v Stone [1951] AC 850: Pl hit by cricket ball and seriously injured; ball travelled 100 yards before hitting her, clearing fence 17ft high and 78 yards from batsman; ball hit out of ground only 6 times in 28 yrs. No liability. “…an ordinarily careful man does not take precautions against every foreseeable risk”, per Lord Oaksey. “…law of negligence is concerned less with what is fair than with what is culpable”, per Lord Radcliffe. • University of Wollongong v Mitchell (2003) Aust Torts Reports 981-708 • Roads and Traffic Authority of NSW v Dederer (2007) 238 ALR 761: probability concerns probability of the harm, not the conduct that leads to the harm. s 9(2): severity of likely injury Risk of greater damage than normal may increase obligations of potential Def. • • • • Eg. Swinton v The China Mutual Steam Navigation Co Ltd (1951) 83 CLR 553: Wharf labourers involved in handling cargoes of mustard gas. Def under higher obligations due to unusually serious nature of the risks. Eg. Paris v Stepney Borough Council [1951] AC 367: Pl, garage hand with only one eye, blinded in other eye by splinter from bolt; goggles not supplied by employer Def. Although no greater risk of injury, lack of goggles increased risk of injury being more serious. Def knew of Pl’s condition and should have supplied goggles: Def liable for negligence. See also, Haley v London Electricity Board [1965] AC 778: Pl, blind, injured falling down trench dug by Def. Blind people foreseeable and greater risk of injury, although not risk of greater injury. But, see warning from Callinan J in Roads & Traffic Authority v Dederer: “seemingly minor mishaps can sometimes cause grave injuries”. Risk of harm assessed as at time of injury: H v Royal Alexandra Hospital for Children (1990) Aust Torts Reports 81 – 000: Def hospital negligent in respect of inadequately screening blood for HIV after risk identified by science and technological advances. s 9(2): burden of taking precautions Requires a cost-benefit analysis. • Roads & Traffic Authority of NSW v Dederer [2007] HCA 42 • Def will have to justify any lack of precautions: Eg. Shepherd v SJ Banks & Son P/L (1987) 45 SASR 437; Caledonian Collieries v Speirs (1957) 97 CLR 202 • Inability of Def to afford doesn’t = impracticable: eg. PQ v Aust Red Cross Society [1992] 1 VR 19 • Romeo v Conservation Commission [1998] HCA 5: limited resources available to public authorities relevant, as were competing priorities. • The fact that the risk could have been avoided by doing something in a different way does not in itself give rise to liability: s. 10(b) CLA. See Graham Barclay Oysters v Ryan (2002) 211 CLR 540. s 9(2): justifiability – social utility • • • See Watt v Hertfordshire County Council: “If this accident had occurred in a commercial enterprise without any emergency there could be no doubt that the servant would succeed. But the commercial end to make profit is very different from the human end to save life or limb”. Cf. Cth v Winter (1993) 19 MVR 215 (police sergeant setting up road block held liable for hazardous manoeuvre). E v Australian Red Cross Society (1991) 27 FCR 310 (on appeal (1991) 31 FCR 299): emphasis placed on the effect certain precautions would have had on blood supply. “…to take into account the effect upon the blood supply is to say that a person in the position of the …respondents was entitled to give priority to the interests of all blood users – and everyone in the community is a potential blood user – over the interests of the relatively small number of individuals who might receive infected blood. To so say is to make the present applicant bear the burden of protecting the wider public interest.” (at 313). • Cf with PQ v Australian Red Cross Society [1992] 1 VR 19: the Def’s argument that it was a charitable organisation with limited resources, partly staffed by volunteers was rejected by Court based on reasoning in Goldman v Hargrave. Categories of risk – No Proactive Duty to warn of obvious risks: s 15(1) • Meaning of obvious risk: a risk that in the circumstances would have been obvious to a reasonable person in the position of that person (s. 13(1)). • See Qld v Kelly [2014] QCA 27 • See Roads & Traffic Authority v Dederer; and Woods v Multi-Sport Holdings P/L (2002) 208 CLR 460. – Inherent Risk: no liability for materialisation of inherent risk. Defined as “a risk of something occurring that cannot be avoided by the exercise of reasonable care and skill” (s. 16) (see Rootes v Shelton (1967) 116 CLR 383; Woods v Multi-Sport Holdings). – No liability for personal injury suffered from obvious risks of dangerous recreational activities: s. 19. Good example is Doubleday v Kelly [2005] NSWCA 151 (7 yr old injured while attempting to roller skate on a trampoline – Def liable because of age of child). Case law activity: Read Qld v Kelly Find one recent case example of each of the following: ‘Inherent risks” and “Dangerous recreational activities” Acknowledgements – References • • • • • • • • Danuta Mendelson, The New Law of Torts (2nd ed 2010), published by Oxford University Press. Rosalie Balkin and Jim Davis, Law of Torts (4th ed, 2009) published by LexisNexis Butterworths. Julia Davis, Connecting with Tort Law (2012) published by Oxford University Press. Bernadette Richards, Karinne Ludlow and Andy Gibson, Tort Law in Principle (5th ed, 2009) published by Thomson Reuters Lawbook Co. Frances McGlone and Amanda Stickley, Australian Torts Law (2nd ed 2009) published by LexisNexis Butterworths. Martin Davies and Ian Malkin, Torts (Focus Series, 6th ed, 2012) published by LexisNexis Butterworths. Carolyn Sappideen, Prue Vines, Helen Grant and Penelope Watson, Torts Commentary and Materials (10th ed, 2009) published by Thomson Reuters Lawbook Co. Sarah Withnall Howe, Greg Walsh and Patrick Rooney, Torts (LexisNexis Study Guide, 2nd ed, 2012) published by LexisNexis Butterworths.