Matthew-Treherne-project-findings

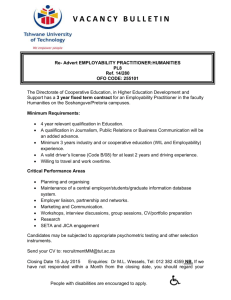

advertisement

Faculty of Arts Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts Project findings and outputs Matthew Treherne (m.treherne@leeds.ac.uk) Abi Rowson (a.rowson@leeds.ac.uk) 9 June 2011 This document is available electronically at https://elgg.leeds.ac.uk/illmt/weblog (University of Leeds login required) Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 2 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 Contents 1. Foreword 2. Summary report 3. Research and employability: key messages 4. Student-facing material a. How can research-led teaching help make you more employable? b. Sample alumni case studies c. Employable competencies – and how your studies can help you prepare for job applications and interviews d. Case study: What does studying Dante (or anything in the arts and humanities) at Leeds have to do with your future career? 5. For staff a. Experiencing research-led teaching: reflections on auditing two modules in the Faculty of Arts b. Discussion paper: Maximising the employability benefits of research-led teaching in the Faculty of Arts: three opportunities for development 6. Appendix: Summary of student focus groups 3 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 4 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 1. Foreword 5 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 6 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 Foreword This pack summarises the findings of the project on “Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts”, presents some resources for use with current and prospective students, and offers suggestions to help the Faculty of Arts develop connections between research-led teaching and employability. It is a good moment to be thinking of these issues. Nationally, in the wake of the new funding regime for higher education, the role of the arts and humanities in universities is subject to considerable debate. Within the University of Leeds, the issue of employability has risen up the University’s agenda. And research-led teaching remains an institutional priority, refreshed by the work of the Curriculum Enhancement Project. Overall, the project’s findings should give us confidence in this context. There is evidence here to suggest that the arts and humanities can hold their own in the current climate; that paying attention to students’ development of employable skills need not detract or distract from core academic values; and that the distinctive research-led teaching we offer is a great asset to the Faculty. Employability is not the only reason for studying in the Faculty of Arts – our students love their subjects for their own sake – but we can be confident that, in career terms, taking a degree here is an investment which will pay long-lasting dividends. This fundamental proposition is sound: the challenge lies in communicating that proposition clearly and convincingly to future and current students, in enabling them to articulate the benefits of their academic experience at Leeds to future employers, and in ensuring that we make the most of future opportunities to draw together our work in employability and in research-led teaching. **** The project benefited enormously from the support of many people. The project would not have been possible without the award of a University Teaching Fellowship in 2010, for which I am immensely grateful. This in turn enabled Abi Rowson to work on the project. Abi’s exceptional ability to frame and analyse the issues, to work effectively with staff, students and alumni, and to manage the project has defined and improved immeasurably every aspect of the work we carried out. I cannot imagine a better colleague to work with on this project. We were fortunate to have an advisory board who were generous with their time and insights: Rafe Hallett; Sue Holdsworth; Tess Hornsby-Smith; Caroline Letherland; Simon Lightfoot; Kevin Linch; Paul Rowe; Chris Warrington. Other colleagues who supported the project in various ways include: Julia Braham; Chris Butcher; Kitty Dixon; Helen Finch; Frank Finlay; David Gardner; Viv Jones; Aaron Meskin; David Platten; Penny Robinson; Brian Richardson; Kate Swan; Victoria Treherne; members of the University’s Employability Committee; members of the School of Education. Peter Blackburn, James Martin, Anne Siddell and Oliver Vergo are Leeds alumni who gave their time freely, spoke frankly and had an enormous amount to offer. Students on modules ITAL3020 (Dante, Purgatorio and Paradiso) and PHIL3722 (Philosophy and Literature) were patient as we audited their modules, and contributed enthusiastically to focus group discussions. Warmest thanks to all these people for their generosity, support and goodwill. Matthew Treherne 8 June 2011 7 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 8 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 2. Summary report 9 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 10 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 Summary report The project 1. This project, funded by a University Teaching Fellowship, and led by Abi Rowson and Matthew Treherne, examined the ways in which the distinctive research-led teaching in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Leeds prepares students for employment after graduation. We aimed to test the hypothesis that the Faculty’s work in research-led teaching supported undergraduates’ development of employable skills; to articulate with renewed clarity the relationship between research-led teaching and employability; and to identify priorities to enhance and deepen the connection of research-led teaching and employability. We ran focus groups with students, held interviews with alumni, observed teaching, and analysed published material. The project ran from January to May 2011. Research-led teaching and employability 2. Our findings tend to confirm the frequently stated view that an arts and humanities curriculum fosters and develops transferable skills. In particular, the project suggests that skills in communication, creativity, problem-solving, project management, interpersonal skills, as well as a positive attitude towards life-long learning, are developed in arts and humanities degree programmes. 3. However, this overarching account of the connections between the arts and humanities and employability can be enriched, especially in relation to the Leeds experience. A number of key points emerged to add nuance to that overarching account: a. The true benefits of an arts and humanities education are long-lasting, felt over the course of a career rather than in the stages immediately following graduation. This is a significant message, as it suggests that the full career value of a degree from the Faculty of Arts will not be reflected in data showing employment patterns six months after graduation; b. The specific characteristics of a research-led experience offer considerable opportunities for students to build employable skills and distinctive experience; c. There are further, as yet underexploited opportunities to draw on the shifting landscape of academic research, with benefits for employability which should not be neglected – including collaborative work, impact, and interdisciplinarity; d. In order to maximise the career benefits of a research-led education, it is important for students both to develop awareness of the long-term benefits of that education, and to develop compelling case studies for use in the short-term, including at the stage of job applications. These case studies might include: individual research projects, such as dissertations, or within modules; involvement or engagement in the Faculty’s research environment, such as through the UGRS scheme; participation in interdisciplinary masterclasses. These compelling case studies would enable students to demonstrate the general benefits of their education at Leeds, and to give rich, eye-catching, individualised evidence of high-level employable skills. 11 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 4. By auditing two sample modules across a full semester, we were able to identify ways in which students developed key skills through an emphasis on research-led teaching were evident as modules were audited. Analysis, communication, interpersonal skills, flexibility, time management and research were particularly evident; there were also opportunities for students to display and develop teamwork and leadership skills, although these were less prominent and not explicitly identified by module leaders or students themselves. Students’ attitudes 5. Students’ awareness of the nature and value of study in a research-led institution is not always as clear as it might be. Our focus groups suggested that whilst many students appreciate the benefits of studying in a research-intensive environment, and are able to identify excellent examples of good practice, some students lack confidence in what research-based learning requires, and have some concerns about the limitations of research-led teaching. Perceived benefits of research-led teaching included: The enthusiasm of lecturers who were teaching the subject they researched; The opportunities for exposure to “live questions” in a discipline, rather than a fixed idea of a subject; A sense that rubbing shoulders with expert researchers was “what university was about”. Perceived pitfalls included: Feeling intimidated by lecturers’ expertise; A lack of confidence in grappling with complex issues and data sets; Concern that the curriculum might be narrowed to reflect academics’ particular research interests, rather than exposing students to the full range of the field; Academics being primarily concerned with research, and therefore less interested in student education. 6. Students were aware of the key attributes required by employers, but struggled to articulate the ways in which their degree programme helped them to develop those attributes. The most pressing concern for the Level 3 students in our focus groups was the first job after graduation, rather than long-term considerations (this may differ at other stages of a student’s career). 7. When students spoke of their motivations for studying programmes in the Faculty of Arts, they emphasised the enjoyment of the subject, as well as the hope that their studies would make them more employable. Alumni views 8. In-depth interviews were carried out with four alumni at different career stages, and in different sectors. The alumni were very positive about the value of their arts and humanities education at Leeds, which they saw as having paid long-term dividends. They were warm, too, about the idea of research-led 12 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 teaching, and about its positive effects on students’ future careers. They emphasised the importance of the following: A flexible, internationally-informed approach to work and study; The development of interpersonal skills; The ability to articulate arguments and synthesise material; Confidence in expressing the value of the skills gained in studying arts and humanities. The relationship between academic and extracurricular experience 9. In discussing the key attributes of employable graduates, alumni emphasised the importance of combining both academic and extracurricular experience. The value of research-led teaching in developing employability therefore needs to be set alongside the broader experiences developed by Leeds students (as articulated through LeedsforLife). Whilst academic study in a research-led institution can directly or indirectly develop all key employable skills, it is when that academic excellence is combined with broad experience that employability is most effectively developed. 10. Given students’ interest in and enthusiasm for their subjects, messages about the value of research-led teaching for employability should be set alongside confident messages about the intrinsic value of the discipline and the broader benefits of the Leeds experience, as expressed in LeedsforLife. Marketing and Admissions 11. Although this project did not work directly with prospective students, its findings have ramifications for marketing and admissions. The message about the value of research-led teaching in the arts and humanities, and its connections with employability, requires careful articulation. We hope that this project can support the development of compelling and coherent messages about the value of studying arts and humanities at Leeds. Outputs 12. In order to ensure that the findings of the project benefit the widest possible constituency, including prospective and current students, and academic staff, the project has produced the following set of resources: a. For marketing: a short set of key messages about the benefits of the distinctive Leeds researchled education in the Faculty of Arts, together with evidence underpinning those messages b. For current students: a suite of material articulating the benefits of research-led teaching, designed to be integrated into existing resources, in particular the LeedsforLife website, module resources and the VLE, student handbooks, and Careers Centre material: i. A short, student friendly account of what research-led teaching is and how it supports the development of employable skills; ii. Drawing on real-life examples, sample questions from job application forms and job interviews and suggestions as to how students’ engagement with the research process can enrich answers to those questions; 13 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 iii. A case study based on a sample module, demonstrating the links between research-led teaching and employable skills; c. For staff: i. A brief article by project leaders including reflections on the implications of the project for teaching practice; ii. A position paper suggesting three opportunities for development In addition, quotes from student focus groups – which are illuminating and, at times, salutary – are transcribed in an appendix. Recommendations 13. Our findings and recommendations are intended to support and enrich the significant changes currently underway in student education at the University of Leeds, in particular through the Curriculum Enhancement Project, and the implementation of the Employability Strategy. They are also intended to inform marketing practice in the Faculty. Although we have some specific recommendations, the project’s findings are intended to help shape the conceptual framework within which these issues are considered, rather than set out a full programme of activities or policy change. 14. The benefits of research-led education for students need to be communicated repeatedly, clearly, and credibly. The credibility of the message is largely dependent upon the messenger – our experience of the project showed (unsurprisingly) that students were much more receptive to the idea of the employability benefits of their education when those benefits were explained by an alumnus than by us. The outputs supporting this have attempted to reflect this, by drawing on real-life examples from Leeds alumni where possible. 15. In terms of the employability agenda, the case for research-led education in the arts and humanities is compelling. We have attempted to make that case in as detailed, accessible and convincing way as possible in the resource intended for marketing. We recommend that that resource now becomes a “live” resource for the Faculty, drawn on as appropriate in communication with prospective and current students. 16. The student-focused material we have produced should be adapted as required, and made available to students in the appropriate ways, in particular within student handbooks and module material. 17. The project supports the notion that every student in the Faculty should have the opportunity to carry out a research project as part of their degree programme. We believe that such a project, if backed up with a clear sense of the employable skills gained in carrying out research, can provide an invaluable individual case study for each student to use in making job applications. 18. The University’s Employability Strategy rightly states that employability should be seen as the responsibility of the whole institution. We believe that by emphasising the connections between research, student education and employability, it is possible to encourage that shared ownership. At the level of module planning, employability should not be seen as a distraction from academic excellence, but the links between the two notions should be emphasised. Thinking around personal 14 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 development – including through personal tutoring and LeedsforLife – should encompass, where possible, academic development as a key part of career planning. A consequence of this “joining-up” of thinking will be to challenge the view we found expressed by some students that academic study in the arts and humanities was somehow separate from the serious business of launching and developing a career. 19. We have identified three key opportunities for deepening students’ experience of research-led teaching in ways that will enhance employability in distinctive ways. These are treated in more detail in a discussion paper (5b), and focus on questions of impact; interdisciplinarity and collaboration; and individualised experiences of research. 15 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 16 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 3. Research and employability: key messages 17 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 18 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 Why do a Leeds degree in the arts and humanities? Key quotes and ideas about employability and research-led teaching Research-led teaching in the arts and humanities provides you with skills that will equip you for longlasting career success “The generic and ‘transferable’ skills gained from research can be applied to almost any situation.” Leeds graduate JH Italian and Geography (2010); recently appointed to Civil Service Fast Stream “I have witnessed some careers ‘top-out’ because individuals lack the requisite communication and leadership skills. I would advise arts graduates to have confidence in the high-level skills that they develop through their degrees.” Leeds graduate, English (1986), Executive Search Consultant The skills needed by today’s graduates to succeed in the world of work: “Interpersonal skills; listening skills; being open minded and able to see different perspectives; inter-cultural awareness and a global perspective; ‘hard graft’; a consensual approach; common sense; good written communication.” Leeds graduate, Philosophy (1962), former Chairman, Nestlé UK “You go into the humanities to pursue your intellectual passion; and it just so happens, as a by-product, that you emerge as a desired commodity for industry.” Damon Horowitz, Director of Engineering, Google; cited in Times Higher Education, 19 May 2011 “Most employers are less interested in the precise details of what graduates have studied than in what the experience has taught them…. What matters is that graduates have the framework which allows them to keep on learning.” Richard Lambert, CBI Director-General, November 20101 The arts and humanities are so valuable for management skills that many US business schools are now introducing arts and humanities courses into their programmes. New York Times, 10 January 2010 “Today’s graduates, over their lifetimes, will experience change at an unprecedented pace. They will have not one career but perhaps many. To cope with this kind of change, they will need self-confidence and a sense of purpose couple with adaptability and a capacity for continuous learning. A familiarity with the body of knowledge and methods of inquiry and discovery [i.e. research methods] of the arts and sciences and a capacity to integrate knowledge across experience and discipline may have far more lasting value in such a changing world than specialized techniques and training.” Carol M. Barker, Carnegie Corporation of New York2 1 The Council for Industry and Higher Education Annual Lecture, Thursday 11 November 2010. “Liberal Arts Education for a Global Society”, http://carnegie.org/fileadmin/Media/Publications/PDF/libarts.pdf [accessed 2 June 2011], p. 7. 2 19 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 The outstanding communication skills you develop will be a key asset “Any success in my career has really been down to skills such as written and verbal communication and interpersonal skills.” Leeds graduate, English (1986), Executive Search Consultant Graduates in arts and humanities are “well-trained in writing and presenting, making them natural fits for marketing, training, and research.” Tony Golsby-Smith, Harvard Business Review, March 20113 “And then there are those essays, dissertations and other written assignments. … keep in mind just how much good presentation, correct spelling and proper use of grammar help. Once you move into working life, sloppiness on those aspects can undermine confidence in what you’re saying. Get them right now and you’ll keep them right for the future.” CBI/NUS, March 20114 Your studies will give you the opportunity to develop interpersonal skills “The ability to ‘get under the skin’ of customers and employees to discover their real needs and concerns demands something other than surveys, which yield superficial information. Instead, you need keen powers of observation and psychology — the stuff of poets and novelists.” Tony Golsby-Smith, Harvard Business Review, March 20115 You will build habits of innovation, creativity and problem-solving which will enable you to take on a wide range of work situations “My degree from Leeds gave me the skills to cope with the recruitment exercises; I was confident in analysing long and complex texts and I was confident, too, in contributing to the work of a group.” Leeds graduate, Italian and Geography, 2010, recently appointed to Civil Service Fast Stream In studying the arts and humanities, you need “to be curious, to ask open-ended questions, see the big picture. This kind of thinking is just what you need [in business] if you are facing a murky future or dealing with tricky, incipient problems.” Tony Golsby-Smith, Harvard Business Review, March 20116 “Want Innovative Thinking? Hire from the Humanities”, http://blogs.hbr.org/cs/2011/03/want_innovative_thinking_hire.html [accessed 2 June 2011]. 4 Working towards your future: Making the most of your time in higher education, www.cbi.org.uk/pdf/cbi-nusemployability-report.pdf [accessed 2 June 2011], p. 19. 5 “Want Innovative Thinking? Hire from the Humanities”, http://blogs.hbr.org/cs/2011/03/want_innovative_thinking_hire.html [accessed 2 June 2011]. 6 “Want Innovative Thinking? Hire from the Humanities”, http://blogs.hbr.org/cs/2011/03/want_innovative_thinking_hire.html [accessed 2 June 2011]. 3 20 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 “Show me that you were captivated and driven by something.” Michael Moritz, CEO of Sequoia Capital, giving interview advice to arts and humanities research students, Stanford University, 11 May 2011 “If I’m going to really launch you on a career or path where you can make a big impact in the world, you have to be able to think critically and analytically about the big problems in the world.” Garth Saloner, Dean of Stanford Business School, explaining the decision to include arts and humanities in his curriculum 7 You will learn how to research new topics independently, deal with large amounts of information, and explain your findings to others “The research and writing skills I gained from my English degree were immensely useful when working as a market analyst following companies, predicting winners and losers, writing reports and advising fund managers.” Leeds graduate, English, 1986; now senior Executive Search Consultant, Egon Zehnder International “The fact is that managing time, prioritising and deciding how best to allocate your energies are central to effectiveness at work. Your course gives you an ideal opportunity in those self-management skills.” CBI/NUS, March 20118 Senior managers need to be able to “synthesise information from many different sources, reflect on its implications for the organisation, apply judgement, make trade-offs, and arrive at good decisions.” McKinsey Quarterly, January 20119 You will acquire a flexible approach which will serve you well in the world of work Doing research requires “patience and flexibility. You need to be patient enough to accept the fact that the evidence you find may not necessarily support you in your task, and that in fact a lot of the existing evidence and scholarly research is often contradictory. You need to be flexible enough to realise that your arguments and ideas will grow, develop, and change as you go deeper into your research topic.” Leeds graduate, Italian and Geography, 2010 “The cultural sensitivity and broad perspective I gained from studying history, politics, philosophy and literature in my degree was hugely beneficial in later life” Leeds graduate, Spanish and Portuguese, 1976; now senior executive and board member, United Business Media Cited in “Multicultural Critical Theory. At Business School?” New York Times, 10 January 2010. Working towards your future: making the most of your time in higher education, www.cbi.org.uk/pdf/cbi-nusemployability-report.pdf [accessed 2 June 2011], p. 18. 9 Derek Dean and Caroline Webb, “Recovering from information overload”, McKinsey Quarterly, January 2011. 7 8 21 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 22 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 4. a. b. c. Student-facing material Research-led teaching and your future career Sample alumni case studies Employer competencies – and how your studies can help you prepare for job applications and interviews d. Case study: what does studying Dante (or anything in the arts and humanities) at Leeds have to do with getting a job? 23 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 24 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 Research-led teaching and your future career What is research-led teaching? The University of Leeds is a research-intensive university, which means that your academic tutors, in addition to teaching, are engaged in their own research. At Leeds, a significant proportion of the quality of research in the arts and humanities has been judged as world-leading or internationally excellent. This excellence in research underpins the content of your modules and your degree programme, hence the term ‘research-led teaching’. Your exposure to cutting-edge research helps you to become a researcher yourself. By Level 3, you will have acquired the skills and knowledge to be able to operate as a researcher in your own right, capable of approaching the same type of research questions as your tutors, and able to produce well-researched and argued responses. Within your programme you have both the opportunity to learn from – and challenge, question and debate with – recognised experts in your subject area, coupled with opportunities to explore your own research interests. Why is research-led teaching valuable for your employability? The top ten skills10 that graduate employers are looking for include Communication, Team-working, Integrity, Intellectual Ability, Confidence, Planning & Organisational skills and Literacy. You will have opportunities throughout your programme to demonstrate and develop all of these skills: in researching and writing assignments, in group activities, and in seminars and tutorials. As you embark on your own research, you will work collegially with your peers and with your academic tutors as part of a community of scholars. Embracing this culture of research will benefit your academic performance; it will also mean that you develop skills that employers value highly. It will give you immediate benefits, in terms of strengthening job applications, if you are able to speak confidently about the skills you’ve gained in your studies, about how you’ve made the most of opportunities at Leeds to benefit from our emphasis on research-led teaching, and if you are able to produce a compelling narrative about how you’ve demonstrated qualities in particular aspects of your research (perhaps in a dissertation, or a particular approach to a presentation, or other opportunities to take part in research projects). And it will bring you long-term benefits, lasting throughout your career. You will become: 10 Confident in analysing and presenting complex knowledge. Organisations need individuals who can understand, analyse and present complex information, whatever the subject. Able to approach research questions and understand the research methods used to investigate and establish knowledge. Any organisation must make decisions – from the strategic and the global, to the operational and the local – based on accurate information. Knowing how to approach, investigate and gather relevant information, and knowing how to differentiate between types of information, is vital. Able to plan, research and manage your own research projects. Graduate-level jobs require you to manage your own workload, take responsibility for the quality of your work, and handle complexity. The Council for Industry and Higher Education (CIHE), 2008. 25 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 Able to analyse information, synthesise views, make connections and propose creative solutions. The ability for employees to solve problems through intellectual creativity helps organisations perform effectively, adapt, compete and survive. Able to engage with lecturers’ research in a professional way. Building relationships and working constructively with colleagues – whether peers or more senior managers – is essential if organisations are to flourish. Interpersonal and communication skills are highly valued by employers. Able to reflect on and benefit from your learning. Reflective practice is valued beyond university. Employers need individuals who are keen to learn, who are intellectually flexible, and who are willing to continue developing throughout their careers. 26 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 Alumni case studies James Martin (English, 1986) Leeds alumnus James Martin has had an interesting career path since graduating in English: he has been an RAF pilot, a stock market analyst at the London Stock Exchange, and is now a partner in the global head-hunting firm Egon Zehnder. James thinks that his research and writing skills from his English degree were invaluable at the Stock Exchange— and notes that he witnessed colleagues without this background struggling in this area. Even more important, he thinks, were his interpersonal skills: being able to understand how people behave and what makes them tick, being able to communicate with people from different backgrounds, and being able to distil stories down to 30 seconds -a product, to some extent, of reading widely and of engaging in cultural debate. From the Stock Exchange James moved to Egon Zehnder, a global head-hunting firm, where he has been for 15 years. He notes that the skills needed for his current post combine the intellectual and interpersonal. With his considerable professional experience in tracking the careers of successful executives, James comments that some careers ‘top-out’ because individuals lack the requisite communication and leadership skills. He advises arts graduates to have confidence in the high-level skills that they develop through their degrees and not to downplay them: they are just as important-perhaps more so-- than the technical skills learned on more vocational courses. Top Tips: Have confidence in the skills that you develop through an arts and humanities degree – these are extremely valuable to employers. For example: Written and verbal communication Interpersonal skills Able to consider many perspectives/ a global view Analytical skills Research and intellectual skills Peter Blackburn (French & Philosophy, 1962) Peter had little idea about what he wanted to do when he graduated from Leeds, and so he took the advice of a friend and joined a chartered accountancy firm. In what was to become a very successful career, Peter moved up the ladder of food and confectionary giants Rowntree Mackintosh and Nestlé, eventually becoming Chief Executive of Nestlé France and Nestlé UK. Peter puts his success down to luck, his French language skills and ‘hard graft’ – doing all jobs asked of him to the very best of his ability, whatever they entailed. He also advises new graduates to try to develop the following essential skills: Interpersonal skills Listening skills Being open minded and able to see different perspectives Inter-cultural awareness and a global perspective A consensual approach Common sense Written communication skills Top Tips Make the most of your already-existing networks of friends, family and colleagues. Do everything to the best of your ability. Listen to other points of view and learn from them. 27 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 28 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 29 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 30 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 What does studying Dante (or anything in the arts and humanities) at Leeds have to do with your future career? On the face of it, modules in the arts and humanities can seem to have very little to with your future career. I like to start my modules – on medieval and Renaissance Italian culture – by asking students why they’ve chosen to study the topic in hand. They talk about their interest in the topic, the chance to explore some of the best-known works of European literature and art, the fascination of a cultural context so different from our own. I don’t think anybody has said they have chosen to study my modules “because it will get me a job”. I think things are a little more interesting than that, however. In fact, I’m sure that studying arts and humanities subjects in a research-intensive environment, can bring great benefits to students’ future careers. Take the example of a Level 3 module I teach, on Dante’s Purgatorio and Paradiso. This is usually a very enjoyable module to teach, because Dante inspires and enthuses students; it also draws directly on my own research, and a research strength of the University of Leeds, so it’s great to be able to draw students into our research culture around Dante. For instance, in one academic year, students had the opportunity to meet an American scholar who was visiting the Leeds Centre for Dante Studies; they also attended talks by our Newton International Post-doctoral Fellow and by a PhD student, who discussed their research with them; and they had the opportunity to attend a national study day organised by the Centre. I’d like to think that students on this module feel welcomed into our research culture, and get a strong sense of the excitement of working on Dante in a rich research environment. So what has all this got to do with students’ employability? I’ll set my thoughts out against some of the core competencies sought by employers. Flexibility I’d say this is absolutely one of the top qualities you need to succeed in this module – not least because it’s one of the qualities Dante expects of his readers. For instance, the opening of the Paradiso sets out how old habits of thought need to be set aside in order to understand how Dante is presenting Paradise. If you’re not willing to be flexible, you’ll never get what this is about. You also need to take Dante (or any medieval author) on his own terms, at least at first, if you want to try and understand him: if you try and apply modern values or categories, you will immediately go wrong. And the important thing about studying Dante in a research-intensive environment such as that at Leeds is that you find yourself encountering many different approaches. One of the visiting speakers I mentioned earlier talked about Dante’s relationship to visual art, and it was great to see students adapting to this way of thinking about a literary text. I’d also expect students to be reading widely in the vast range of Dante scholarship, being receptive and questioning of the new ideas they come across. All of this is developing the kinds of habits and dispositions you’ll need in the world of work – just as in Dante, problems are often unexpected, approaches need to be adapted, new ideas can be challenging. Leadership and decision-making On the face of it, this is not something that can be demonstrated through the study of Dante. But thinking about it, I’m often impressed by the ways in which students do display leadership. When they make a presentation, they often put forward ideas that are new to the class, for instance. And because Leeds students are lively and intellectually curious, it’s not always an easy job to persuade them of these new ideas – but trying to do so is great practice at leadership. Leadership doesn’t have to mean bossing people about, or dominating a room – in fact, good leadership rarely means those things – but rather involves taking a lead by identifying an issue others have neglected, setting out ways of thinking about it, calmly explaining, adapting approach where that’s they right thing to do. These are all skills I see developing in the seminar room. 31 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 Interpersonal skills I’ve tried to encourage students to work together on the module, not in the first instance because of employability, but because it’s fun – and because Dante himself had such a clear belief that human beings are fundamentally social animals. For this module, students form reading groups to read sections of the text together, and they put together brief reports. Students also interact in seminars, asking each other questions, sometimes disagreeing with each other. I wouldn’t measure or try and assess this, but I’d say that students who are engaged in class, who work together to understand the text, and who bring the best out of each other, are likely to perform better on the module than they would if they were disengaged. And, in common with most academics, when it comes to writing references for students I would certainly mention if I had noticed a student working particularly well with his or her peers. Indeed, increasingly, employers asking for comments specifically on this issue. Communicating with impact As a student, I used to think that the key to getting good marks was writing difficult prose – because if I’m hard to understand, that means I must be clever. Now, I can see how wrong I was. Be clear. Don’t make your writing style more complex than it needs to be. Show me the ways you’re approaching a question or issue. Equally, when speaking – whether in presenting or in discussing – be clear. If you need to use jargon, explain it. Innovation, creativity and problem-solving Dante’s poetry is full of problems for us as readers. One of the first problems we come across on this module is the presence of a puzzling character – Cato – on Mount Purgatory. A good seminar discussion on this would think about ways of approaching this problem (Why is Cato so problematic? What would Dante and his readers have known about Cato? Where can we look to find this out? Is there anything in the text that helps us to address this question?) before sharing ideas about what Dante might have been up to, probing and testing those ideas. I love discussing problems like this with students – you can see the students learning from each other, and I’m also always surprised and educated by their ideas. Like so many of the subjects we study in the arts and humanities, Dante challenges students to be creative and innovative in ways they often have not encountered. Being able to manage projects, being results-oriented Students struggle with this. They’re busy, and often have multiple deadlines to juggle. Can you get the essay in on time? Even more importantly, can you go through the various stages you need to undertake to write a good essay – the planning, the research, the drafting and re-drafting, getting feedback? It’s human nature to complain about having too much to do – but I don’t know many people who have succeeded in careers without finding strategies to deal with being so busy, with having multiple projects and deadlines to manage. Integrity It’s easy, and tempting, to blag when you’re talking about Dante. Sometimes, because it’s a daunting topic, students feel they need to drop in references to ideas, texts or major figures – just as very often the notes in their edition of the text do. Every time I teach this module, I notice a learning process: in the first presentations, students often make passing reference to something referred to in their editions – perhaps a biblical passage which Dante seems to be citing, or a reference to an idea as “Aristotelian”. I see my role at this stage as being a bit of a nuisance, asking annoying questions. What exactly do you mean when you refer to that figure or text? Can you explain why it’s relevant here? I try and do it carefully, because the last thing I want to do is embarrass the student. But there’s a really important lesson being learned in the process , about research integrity. The questions underneath are: Have you really thought this through for yourself? Have you checked someone else’s assumptions against the primary evidence? Do you understand the terms you’re using? This 32 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 translates directly into professional integrity. In any professional relationship, it’s crucial that you’re honest. If you’re advising a client or colleague to take a particular decision, for instance, they need to have confidence that you know what you’re talking about, that your advice is grounded in first-hand knowledge as far as possible, that you’re not just repeating something you’ve heard elsewhere. Commercial/sector awareness Can you really develop “commercial awareness” by studying Dante? It might seem that the answer is: of course not. But, without wishing to overstate my case, I’d suggest that there is a connection between studying in a research environment and developing commercial or sector awareness. I try and get students to think about trends and currents in Dante scholarship, to identify these for themselves, to think about where their own thinking “fits”. Students who are performing very well on this module will be able to locate their work within some of these trends, to understand what the current questions are and how they might respond to them. In the commercial sector, this involves thinking about a number of dimensions. What are the forces shaping this market? Where is the market going? How does this company’s products fit on the market? What are the opportunities? These are – in a very different context, and with very different motivations – similar questions to those which a good piece of research might ask. What are the major trends in my field of study? How does this piece of research fit in this particular context? Where should scholarly attention be focused next? Getting used to asking these questions is an excellent way to prepare for building commercial or sector awareness. So: will studying Dante get you a job? On its own, perhaps not. But the skills you develop – if you approach Dante in a serious way, engaging with the research culture and developing strong research habits – will set you on the right path, will serve you well throughout your career, and will help you to see in yourself those competences that employers seek. 33 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 34 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 5. For staff a. Experiencing research-led teaching: reflections on auditing two modules in the Faculty of Arts (Abi Rowson) b. Maximising the employability benefits of research-led teaching in the Faculty of Arts: three opportunities (position paper) 35 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 36 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 Experiencing research-led teaching: reflections on auditing two modules in the Faculty of Arts Abi Rowson We chose to audit two Level 3, Semester 2 modules in order to provide case studies for this project: Philosophy and Literature, in the Department of Philosophy, and Dante’s Purgatorio and Paradiso, in the Department of Italian. We had two reasons for choosing the modules: firstly, we wanted to recruit finalists to take part in our interviews and focus groups and secondly, we wanted to ground the project in the student experience. By attending lectures, seminars and tutorials at the invitation of the module leaders, and by completing the required readings for the modules, I was able to reflect on the experience of research-led teaching from the vantage point of the undergraduate. The audit stopped short of completing any assessed work but assessment was discussed at length in the various focus groups. The experience of ‘being’ an undergraduate was instructive; it embedded the project in the experiences of undergraduate life and refreshed our understanding of undergraduates’ experience of learning. The two modules were chosen quite carefully. Both involved research-led teaching and research-based learning and thus comprised, to a greater or lesser degree, each of the elements Healey describes in his matrix. In both modules, students were taught by experts on the topic, and in both modules, there was explicit encouragement for students to operate as researchers themselves. Students were given research and presentation tasks throughout the module which built towards assessed work --in itself, a piece of research. Evident at this level, too, was the fact that the division between lecturer and student was somewhat porous: lecturers engaged with students as researchers and as sources of new ideas and knowledge-- and expected students to approach their work in this spirit as well. Focus groups revealed that students were not always confident or comfortable with this new-found status. The experience underlined the fact that by Level 3 undergraduates have developed an impressive array of skills within their curriculum – not all of which are recognised or celebrated as much as they might be. There is considerable focus on the skills which are needed to excel in written assessments—and, of course, there are good reasons why essays and exams are uppermost in the minds of students and academic staff—but there are a host of other skills that undergraduates must master in order to succeed. These skills will be at least as important in their future lives and careers; we shouldn’t downplay them or miss the opportunity to celebrate them. A straw poll of four graduate employers11 shows common competencies that each employer regards as essential: Communicating with impact Innovation, creativity Problem-solving and analytical skills Flexibility Leadership and decision making Inter-personal skills/ building relationships There are already many opportunities for students to demonstrate these competencies within a research-led, arts and humanities curriculum. Are students aware that they have these skills and are they confident that they are valuable to employers? This project has highlighted that there may be more that the university/faculty can do on this front. There are clearly many things that the Faculty of Arts is getting right: it is producing highly literate, globally aware, engaged, questioning and reflective graduates. But can we do more to launch 11 These competencies were found in the graduate recruitment materials of the Civil Service Fast Stream, PWC, Cancer Research UK and the BBC. 37 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 graduates into the job market with greater confidence in their own abilities and aware of the valuable nature of their skills? What do we do well? By Level 3: 1. Students are given many opportunities to demonstrate and develop their communication skills – in writing, in group activities, and in seminars/tutorials. 2. Students are asked to operate as researchers in their own right; they are invited to join a community of scholars and to work collegially. Students become confident in reading and presenting complex knowledge. able to approach research questions and understand the research methods used to investigate and establish knowledge. able to analyse information, synthesise views, make connections and propose creative solutions. able to plan, research and manage their own research projects. able to engage with and offer critiques of a lecturers’ research in a professional way. able to reflect on and benefit from their learning. 3. Students develop awareness of and respect for other perspectives and sensitivities, whether local, national or international. What could we do better? Students are well-equipped to compete in the graduate jobs market but may not appreciate the range of skills that they have developed through their curriculum. How can we 1. Build greater awareness in students of the skills that they develop in an arts and humanities researchled curriculum? 2. Build confidence in students of the valuable nature of their skills for employers? Communication Innovation and creativity Problem-solving and analytical skills Flexibility Interpersonal skills and building relationships. 3. Provide further opportunities to demonstrate a wider range of skills such as: Leadership and decision making Group and team work Interpersonal skills and building relationships? A postscript about web technology In the 13 years since I was a Philosophy undergraduate at Leeds there have been changes in the way in which web technology pervades both student and working life. This subject kept cropping up spontaneously throughout the project in various conversations. The all-pervasiveness of web technology brings both help and hindrances for the student; help in the day-to-day practicalities of organising modules online, finding readings, searching out further sources of research and contacting tutors and peers. But hindrances, too, in the form of over-reliance on web technology for solving problems and the risk of web-enabled procrastination, with the 38 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 distractions of internet, blogs, email, and social networks now immediately available. Procrastination has always been a problem --felt acutely in the difficult task of writing essays-- but the clarity of thought needed in order to critically engage, at length, with thorny academic questions is perhaps made more difficult with the constant background buzz of the internet promising as it does instant answers and (somewhat passive) gratification for stimulation. By Level 3, students will know that the answers to their academic questions cannot be found on the internet and that rigorous intellectual engagement is the only route to success. However, they must still learn how to make the best use of technology and learn when and where it is helpful. Students must meet this challenge with motivation, concentration and good time management skills and, in doing so, will learn that the practical skills of getting organised and dealing with procrastination are as important as the intellectual abilities needed to be able to engage with the demands of a degree or, indeed, of a graduate-level job. 39 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 40 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 Maximising the employability benefits of research-led teaching in the Faculty of Arts: three opportunities Position paper As well as testing the careers value of current practices, we also considered ways in which the Faculty of Arts might enrich still further the connections between employability and research-led teaching. We would suggest three areas for development. 1. Interdisciplinarity and collaboration The ability to integrate different approaches is especially valuable. The integration of knowledge informs the widely discussed idea of “fifth-generation innovation”, held as one of the defining features of the knowledge economy.12 Or, as one of our alumni put it, an organisation employing a graduate requires them to be willing to think about the whole range of problems facing the organisation – in a commercial setting, for instance, someone working in research and development needs to be alert to issues of marketing, of accounts, of operational management. As research grows more interdisciplinary, as research councils encourage interdisciplinary approaches to questions and issues, then students should be given opportunities to engage in interdisciplinary research. This can help them to demonstrate innovative approaches to problem-solving, and flexible thinking; it can also bring students to work in collaboration with their peers, thereby demonstrating and developing interpersonal and teamwork skills. Initiatives such as the Faculty of Arts masterclasses, which draw together colleagues and students from across the Faculty to address areas of common interest, are an excellent example of this. As researchers in the Faculty develop interdisciplinary projects and initiatives, we should be alert to opportunities to involve taught students. Similarly, where possible Joint Honours students should be given opportunities to integrate the two halves of their degree programmes. As the role of electives is refreshed in the Curriculum Enhancement Project, personal tutors should find ways to encourage students to draw together and integrate the various aspects of their academic experience. Any chance for students to work and think interdisciplinarily can pay rich dividends both intellectually and in terms of their employability. 2. Impact and public engagement The value of a research-led education for employability can be multiplied when that research environment brings students into contact with contexts beyond academia. That contact can give students the chance to show that they are able to adapt to different situations, and to transfer directly their research skills into new areas. There are already some excellent examples where students are involved in impact activities (such as Dr Rafe Hallett's Research Collaboration, Communication and Enterprise module) As the Faculty continues to develop its work in impact and innovation, with – for instance – its Transformation Fund project for an Arts Impact and Innovation Centre, it should seek ways to integrate students further into its innovative, outwardlooking research culture. 3. Compelling, individualised narratives about the experience of research The long-term benefits of a research-led arts and humanities education emerged very clearly. But to make the most of the opportunities of research-led education in the crucial next step – getting the first jobs after graduation – it is important that students are able to speak convincingly about particular aspects of their experience in a research-intensive university. For this reason, any move to give all students the opportunity to carry out a substantial research project will bring a considerable pay-off in terms of employability. Students will 12 Roy Rothwell, “Towards the Fifth-Generation Innovation Process”, 11 (1994), 7–31. 41 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 need guidance in “translating” their research experience into case studies that can be used in interviews and job applications; but these case studies will establish compelling accounts of how students have benefited from research-led education. Examples might include: - A dissertation that took on a new problem or an old problem in a new way, required the student to acquire a new skill or to bring together different skills, required an adjustment of approach and some degree of collaboration with others, was completed on time, produced new knowledge, was communicated in clear writing and perhaps orally through UG dissertation conferences; - A research project (eg via the UGRS scheme) that involved working closely with an academic, gathering evidence, presenting material, completing the project on time. 42 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 6. Appendix: Summary of student focus groups 43 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 44 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 Appendix: Indicative quotations from employability focus groups Participants: Level 3 students in Philosophy, History and Modern Languages and Cultures Facilitator: Abi Rowson Quotations are from multiple focus groups held in March-May 2011. References to individual academics, Schools and employers have been excised. What are you going to do when you graduate? “…people said ‘if you have a language you’ll get a job anywhere’.” “…I want to do something a bit more exciting than being a teacher.” “…we’ve had no real time to think about it, you’ve just got to do your work, and then you think, well hang on…” “I don’t just want to be sitting in an office.” “You have to have an epic CV to even be considered for a job [in media]…it’s off-putting.” “You have to have work experience, and find time to do that…” “ I took a careers module last term, and I had to attend careers presentations of [accountancy companies], and I thought, no, these aren’t for me…there was one company which came which was **** restaurant, and they do a graduate scheme…and I’ve got an interview…and it would be amazing.” “I like money, so I’m thinking possibly finance, possibly marketing.” “I’m thinking about working behind the scenes in radio – maybe becoming a radio producer.” “I wanted to work in the Civil Service…I’ve got an offer from the National Audit Office...they will sponsor my chartered accountancy qualifications.” “I’ve got an internship at [investment bank] …there is a high likelihood of a graduate job so long as you don’t muck up.” “I applied for loads and got rejected before being offered this [internship].” “I’m going to do a teaching qualification in Thailand…a CELTA.” “I’m applying for two different sorts of Master’s…an MA in Human Rights and an MSc in Occupational Therapy, which is more vocational. The Occupational Health is more… sensible because it’s funded by the NHS and there is almost a guaranteed job at the end. Whereas the Human Rights is more interesting, and I have to fund it myself, and then it’s more difficult getting a job.” 45 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 What career skills are graduate employers looking for? Time management Research skills Critical analysis Confidence IT skills Argumentation Interpersonal skills Flexible/adaptability “being able to turn your skills to different tasks” Team work Organisation Written communication Presentation skills Social skills Entrepreneurial skills Common sense Numeracy skills Languages Diplomacy Willing to put the work in Motivation Problem solving Communication Which of these skills do you think you are weaker at? Commercial awareness –“…knowledge of the environment and context in which they are working” Leadership – “Telling people what to do” /“Delegation” /“We never really do group presentations”/ “Increasing morale”/ “Bringing the group together” Persuasiveness – “Is this a negative thing?” Team work –“Not much opportunity to work in a team.” Entrepreneurial skills Flexible – “I’d automatically think of being flexible time-wise, but being flexible with your skills as well…” What do you gain from contact with expert researchers, their methods and their findings? “It has impact on us when lecturers are super-passionate about their subject.” “It’s really nice. It makes you feel as though you want to get into it as well.” “I’ve noticed it more in this last [final] year…whereas before there’s been some really boring stuff.” “I was at **** University for my first two years, and I don’t know if it’s because it’s final year now, but I can see a real difference between **** and here…when I was studying ***** at **** it was with Professor ***** …he was really interesting but…he seemed to have a very set idea about what he was telling us…whereas I feel as though [at Leeds] we’re getting more ideas from all over the place. “ “Final year has been a lot more interesting… we’re pointed in the direction of what’s out there, and we have to find it.” “It can be quite scary, because we are treated like academics…whereas I don’t feel like that at all…I’ve not had that experience and never at that level.” “It’s what university’s about…you get the chance to experience learning from somebody who is at the cutting edge of their field.” “It’s good being taught by someone who is enthusiastic.” 46 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 “The tutor’s research is so specific that it will maybe touch on one lecture during the module. What we gain from their research is therefore quite narrow.” “In [School ***** ], you get [research-led teaching] a lot – my tutor is always bringing in other experts to things—we can always talk to them. And she lends us books and helps us to narrow our research to make sure we’re not spending too much time on things that are unavailable. She’s really enthusiastic.” How do you approach your own research (essays/presentations etc.)? Does your research follow the idealised model outlined in the diagram above? “[My research] is quite chaotic because when you read, I don’t know how to select what to read… I have something here, and something here, and then at the end when I come to write the essay, I just have pages of writing…and I’m unsure how to collate it all.” “I select my books mainly from the reading list and then I try to get a broad selection and write notes from the relevant chapters, and it feels really messy, just quoting things and I just feel like my essay is just a selection of this book here then this book here, but there’s no real…” “I try to colour-co-ordinate sections [of my notes] that are relevant to my essay. And then I try to explain what I’ve read in my own words…but it ends up so confused I’m not organised in my thoughts enough to be able to develop the argument”. “I find it hard to get an argument sometimes.” “I always feel as though I do it in the wrong order…You’re supposed to read all these texts first to see what interests you and then put it together, but I feel that because we’re given these essay titles and we’ve got to look at what that’s dealing with, and then you go and make a bit of a plan and then you go and do your reading, you’re only reading little bits here and there. So you could be reading something that it really biased…and you’ve got to try and notice that…otherwise you’ve got this really one-sided view and I think it’s hard…to remain focussed. I feel as though when I’m doing my reading, I tend to get stuck on one point… and I find quotes and I think, oh, that’s good, that’s good and then I’ve got about ten quotes and I don’t know which one to use!” “I don’t think we’re taught enough about essays. All I can remember is my A Level structures, which were fine for A Level, but not for university. I know there are classes you can go to, but I think there should be more in the department. It’s all very well your teacher saying you need to do this, this and this. But I’ve never been taught how to develop an argument effectively. I suppose Dr **** has helped a bit with that. But from Year 1…Like with referencing, they’ll say ‘look on the internet’ and you’ll do it, and it’s still not right.” “It’s hard… you have to have a general idea of what’s going on…and you have to write specifically, so you need to have done all this background reading. There’s so much out there.” “The marks should get higher, shouldn’t they? But mine never do. I write down what I think I’ve done wrong…and then in the next essay there are even more issues.” “I’ve just got a 4,000 word essay back in History…and I did really well, which I didn’t think was going to happen, so I’ve got some confidence that I can do it.” [What do you think you did right?] 47 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 “Interweaving primary and secondary sources…not just sticking to one author and one argument. I didn’t realise I was doing that: it was bit of a fluke, to be honest. He seemed impressed.” “I got feedback on my last two essays…I was told how to improve on them. So I spent all of Christmas on one essay, I didn’t have a life, and I was hoping to get a first…and then I got one of them back, it was good, but it wasn’t as good as I’d hoped…I’d spent so much time on it, I literally thought I couldn’t do anything else. I got good feedback, and think I know where to go from there…the other one, I spent loads of time on and I got a really bad mark—well, not really bad, but…it’s so disheartening when you’ve spent so much time and you’ve worked exactly on what the teacher has said.” “I don’t actually see much of that…all I know is that having spoken to the Department about why there is no course for [Language] for Professional…they said that every single tutor is doing research in their teaching field, so whatever they are researching is what they are teaching us…” [A negative thing?] “Yes and no…” “This is going to sound silly, but if one of the books that you are reading is written by the teacher…and you have quoted them…and then they are marking it…it’s strange…” “[In School of Z] it depends on what module you do…some modules are more research-focussed…and the lecturer might walk in and say—‘look, this is some research I’ve just done, here is a primary source that I have found…whereas in other cases, you don’t really know that what they are teaching you is their research, because they don’t make it explicit. There’s a lot more scope to bring it in…” “I had one lecturer who was really into her research…she kind of focussed on her area of research too much… there were other areas that would have been more interesting…she didn’t really give a balanced overview of the territory.” Undergraduates as researchers? “In [School of Y] … the amount of times we actually come up with something new is pretty minimal. We’re just repeating what someone else has said before.” “One of the questions that I am doing for [module X], there are basically no readings on it…so this is the first time in [subject] where I have felt that I’ve been pushed to go outside just the secondary readings…I have found it hard. I don’t know where to start looking.” “[If my tutors were in this position] they have a wider knowledge and know how to apply that, but I don’t have it. The other people on my course are in the same boat.” [Negative aspects of being taught by an expert?] “I actually avoided all the questions on X because I thought ‘she’s going to know loads about it…I’m going to write on something she knows less about so I’ll get a better mark’.” “It is quite cool to read books written by your own lecturers…but it is weird to quote them.” 48 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 “I have really enjoyed the ***** module and it’s great that the lecturer is so keen on it, but I’m still not going to do the essay on Y because he knows too much about it…I’m going to do an essay on something that he’s not that interested in so that I can’t trip up so many times.” “You have to look at all this stuff, and get every little detail correct…” “At the same time…my dissertation supervisor…it’s great when I speak to her because she goes ‘oh, like on this occasion…’ and she’ll be able to know exactly where it is in the book, and you’re just like, ok, that’s sparking a point…it’s good, that they know everything about a subject…they don’t give you ideas, but you can bounce ideas off them.” “That would be good…but in an essay, when you get less advice from a tutor…and also, my dissertation supervisor doesn’t know much about my topic at all…” “In [School of Z] you can choose your own essay title – you can frame the question and take it to the lecturer and ask ‘is this possible?’ and if it’s not then they can help you.” “You can’t read everything…” “Sometimes it’s annoying how few contact hours we have…maybe one of the reasons is that they’re researching their own stuff. So it could be a drawback.” “Sometimes I feel like I’m teaching myself.” “Sometimes you feel really stupid. Like they are disappointed in everything we have to say.” Processes of research “…look at book titles…there’s so much stuff…with practice it gets easier, skimming things…you can tell immediately if the book is rubbish, or if it’s good.” “chapter titles…” “You have to do a plan…but now I just feel as though I am writing loads of notes…and now I’m going to have to [compress] that into a reasonable, legible essay. I’m just going to write.” “I do a plan of what I already know and do some subheadings. If I find some research that I think is going to be useful, I write it then and there, how it’s going to be, so you don’t have this process of writing notes and then…you know. If you just write out the point, you can take out the sub-headings after. It’s very methodical.” “I usually write a short plan – five bullet points…and then I put a letter next to each one and then I go through my books and highlight the sections with the letter next to it, and then when I’m writing the essay, I can go to it really quickly.” “I write the essay in bullet-point form…I think what angle am I going to take. I gradually expand the plan into an essay.” “For my dissertation I did a chapter plan and expanded on each point, whereas for an essay, if there’s a point I find, I’ll write about it there and then without putting it in order, and then normally…I get distracted really easily, so I write it out on paper and then type it up again…it will be clearer looking back on it.” 49 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 “I find it really hard writing on to the computer.” “I hate proofreading. I’ll write quickly and then read it and think, ‘This sounds like a child has written it’.” “In [Subject Q], it’s sometimes better to start with the source material and come up with the question from that, rather than inventing a question and then looking for the material.” “Or try to find a gap in the secondary material…” “I chose something that I hadn’t done at Leeds before, and read a little bit around it, and then…thought of a question that would apply to that.” “The department allocates your dissertation supervisor…they assign one who could supervise your topic.” “I was given a supervisor that I really didn’t want. I knew they wouldn’t be right for me.” What skills does research require? Being selective in what you read Skim reading Reading the conclusion first Patience—reading page after page Make mind map and list of arguments, then make a structure Linking arguments together I choose a line of argument I write the introduction with no idea about what I’m going to write Editing Finding something of interest Can you think of any situations/ tasks in the work place where these skills might be useful? “It depends what you do. In an office, quite a lot of this will be relevant…” “I’m going to be doing investment research: investigate stocks as part of a team.” “You might have to make a project and then bring it back to your boss and show them what you have done.” “Working out of hours…you might have to stay up late…you’ll need motivation.” What were your interactions with your tutor? “I’d go to him with a plan, and he kind of forced me to do the work as I went along. I know some people struggled to get a meeting with their tutors. But mine was really good, really structured. I was grateful for that...I’m kind of good myself at setting myself deadlines, but not that good!” 50 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 Has your approach to research been successful so far? Will you change it in light of feedback you have received? “I’ve got a lot more selective. Because you’ve got so much to do.” “It’s a time management thing as well. Being brutal about it.” “I’ve realised that…I’ve looked at the essays and the best ones I have done I’ve done strict arguments…like, premise, premise, conclusion. And I think learning that has been very helpful.” “They really nail you for just blabbing. Like they put a line through a paragraph and write ‘what are you trying to say?’. It really makes you think, well, could I have summarised this in a sentence?” “I try to get feedback on all my essays. I still can’t understand why I do well in some and not in others. I don’t know what I do differently.” What skills does research require? List as many as you can. Organisation e.g. referencing as you go along Time management Focus on topic e.g. go back to your research Perseverance Communication with tutors Clarity of argument People management e.g. make a list of what you want to get out of meeting with tutor Avoiding plagiarism Knowledge of sources available Editing Collaboration with peers e.g. reading each other’s work, offer constructive criticism Resilience to criticism Do you think the skills you develop in your course as a whole (i.e. not just essay-writing) are important to employers? Which skills and why? “Our year abroad is something that I always talk about in interviews.I taught factory workers English. Hard. The first day, when you stand up in front of a load of fifty year old factory workers, it’s so scary, it’s horrible. Finding a house, making friends, finding a doctor when you’re sick…it was all a learning curve.” “The only thing that I think my course has really helped me with is being more balanced in my approach to things…Now you have to argue both sides of the story…and I find myself taking that approach in other things.” “We do a lot of presentations…we had to do a presentation whilst being filmed. And that really helps.” “I haven’t had much of an opportunity to do group work.” “It’s hard though, you don’t want to be assessed on group work…” [interrupts] “No, because if you get a dosser…Boys never turn up.” 51 Students, Research and Employability in the Faculty of Arts 9 June 2011 “I take an interest a lot more now, like I watch the news and stuff. I don’t know if that’s my course or if I’m just growing up…[Subject Y] has helped me become much more decisive, rather than sitting on the fence.” 52