here

advertisement

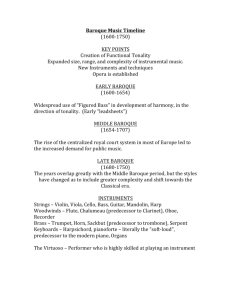

Barocco Siglos 17 & 18 Martin Luther • 95 Theses • Schism from the Catholic Church • Against selling of indulgences • Stated the corruption of the Catholic Church, including the Pope • Arguments spread via the printing press (1440) • Began the Protestant Reformation Council of Trent (1545-1563) • Catholic response to the Protestant Reformation • Cleaned up the corruption • Affirmed their Catholic doctrine • Decided that it was important to educate its members • However, most were illiterate. SOLUTION: Art should be used to explain the profound dogmas of the faith to everyone, not just the educated. SOLUTION: Art should be used to explain the profound dogmas of the faith to everyone, not just the educated. SO… Religious art was to be direct, emotionally persuasive, and powerful in order to fire the spiritual imagination and inspire the viewer to greater holiness. Things to Look for in Baroque Art: •Images are direct, obvious, and dramatic. The Crucifixion of Saint Peter, by Caravaggio, 1601 Caravaggio’s paintings were so realistic that patrons sometimes rejected them as too “vulgar.” In this painting, St. Peter is being crucified. He asked to be hung from his cross upside-down as not to imitate his Lord. The divine light shines on Peter while the faces of the Romans are obscured by shadows. Peter seems to be much heavier than one would expect-three men are struggling to lift him, symbolizing the great weight of their crime. Things to Look for in Baroque Art: •Images are direct, obvious, and dramatic. •Tries to draw the viewer in to participate in the scene. The Ecstasy of St. Teresa, by Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini, 1652 A common theme for Baroque artists was the miraculous moment where the divine met the earthly. Things to Look for in Baroque Art: •Images are direct, obvious, and dramatic. •Tries to draw the viewer in to participate in the scene. •Depictions feel physically and psychologically real. Emotionally intense. Things to Look for in Baroque Art: •Images are direct, obvious, and dramatic. •Tries to draw the viewer in to participate in the scene. •Depictions feel physically and psychologically real. Emotionally intense. •Extravagant settings and ornamentation. Things to Look for in Baroque Art: •Images are direct, obvious, and dramatic. •Tries to draw the viewer in to participate in the scene. •Depictions feel physically and psychologically real. Emotionally intense. •Extravagant settings and ornamentation. •Dramatic use of color. Things to Look for in Baroque Art: •Images are direct, obvious, and dramatic. •Tries to draw the viewer in to participate in the scene. •Depictions feel physically and psychologically real. Emotionally intense. •Extravagant settings and ornamentation. •Dramatic use of color. •Dramatic contrasts between light and dark, light and shadow. The Conversion on the Way to Damascus, by Caravaggio, 1601 Depicted is the moment where Saul (soon to be Paul) has a conversion experience on the road to Damascus. Again we see the Baroque theme of the divine suddenly intruding into the earthly sphere. The man and the horse, who symbolize the ordinary earthly world and are not privy to the full experience, are deep in shadow. Things to Look for in Baroque Art: •Images are direct, obvious, and dramatic. •Tries to draw the viewer in to participate in the scene. •Depictions feel physically and psychologically real. Emotionally intense. •Extravagant settings and ornamentation. •Dramatic use of color. •Dramatic contrasts between light and dark, light and shadow. •As opposed to Renaissance art with its clearly defined planes, with each figure placed in isolation from each other, Baroque art has continuous overlapping of figures and elements. Things to Look for in Baroque Art: •Images are direct, obvious, and dramatic. •Tries to draw the viewer in to participate in the scene. •Depictions feel physically and psychologically real. Emotionally intense. •Extravagant settings and ornamentation. •Dramatic use of color. •Dramatic contrasts between light and dark, light and shadow. •As opposed to Renaissance art with its clearly defined planes, with each figure placed in isolation from each other, Baroque art has continuous overlapping of figures and elements. •Common themes: grandiose visions, ecstasies and conversions, martyrdom and death, intense light, intense psychological moments. Diego Velázquez 1599-1660 de España Las Meninas, 1656 Las Meninas is one of the most profound and enigmatic paintings in the world. You are the king. You stand patiently posing for your portrait, while the royal painter looks somberly back at you from behind his canvas. This is the position into which Velázquez puts the viewer of Las Meninas. It's a big and paradoxical picture, a portrait not of the king and queen – who are only reflected in the painting in a bright mirror at the back of a high, deep room – but of the anxious court mirrored in their – our – eyes. Velázquez shows us the world a monarch sees. The "meninas" are identically-dressed maids who fuss over the Infanta Margaret Theresa, an expensively dressed little girl who even as she plays in front of her royal parents appears on her mettle, under scrutiny. She looks nervously at them while two court dwarfs and a dog are on hand to provide entertainment. One dwarf kicks the dog. It's a grave, chilly little world. No one (except the dog-kicker) seems relaxed and no one looks emotionally close to the monarchs – to us, who stand where they stand. The scene is intensely theatrical, everyone in their costumes and everyone on best behaviour. But at a door in the background a man is coming with news from Spain's vast and, when Velázquez was at work, decaying empire. Presumably Philip IV of Spain was happy with this ingenious conceptual portrait. As painter to the king, Velázquez was showered with honours. But this painting menaces the fabric of reality and the illusion of identity with its consummate game of mirrors. Do kings and queens exist only in the eyes of others? And if that is true of monarchs then who on earth are you and I, transported uneasily by Velázquez into the skin of royalty, attended by a painter who looks at us, polite, exact, and utterly ruthless in his craft? La rendición (surrender) de Breda, 1934-35 How military leaders treat their vanquished enemies conveys much of their character. In early modern Europe, paintings of military victories usually followed a preconceived structure: the victorious commander appeared seated high on his horse, or on a throne, while the capitulating general would kneel on the ground. Degraded and humiliated, the conquered army leader would prostrate himself in submission to the contempt of the triumphant general. But what happens if these dynamics are shifted? What would an image of an honorable commander showing respect for a conquered army communicate? Would a magnanimous leader be seen as weak? And how could abstract concepts such as honor or magnanimity be represented? Velazquez’s The Surrender of Breda revolutionized the genre of military painting precisely by emphasizing that to win with elegance and magnanimity is what defines a great leader, and not merely the ferocious capacity to triumph in combat. Las Meninas, 1656 La rendición (surrender) de Breda, 1634-35