Study notes for the final exam - Lakeside Institute of Theology

advertisement

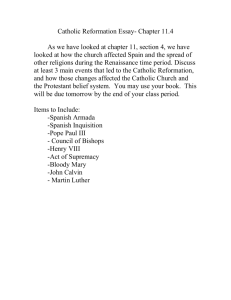

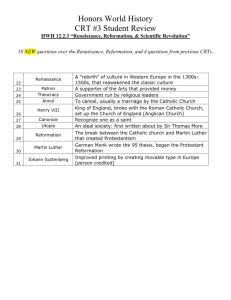

What You Should Know From TH2- Church History 2 Lakeside Institute of Theology 1. What is Church History? The story of the origin, growth and development of the Christian faith and the Christian Church, starting about AD 30, following the resurrection of Jesus Christ. 2. Why is Church History important for us? The Christian message is rooted in the fact that God entered human history; Christianity is uniquely historical. The history of the Church also is the story of how God the Holy Spirit has continued to act through men and women of the faith. Without understanding the past, we are unable to accurately understand ourselves or our faith. A knowledge of Church history can keep us from repeating past mistakes and falling into past errors. 3. What major events in the Catholic Church contributed to an environment that made the Protestant Reformation possible? The Avignon Papacy (or the “Babylonian Captivity” of the Church) – 13091376. Following a decade of severe conflict between Pope Boniface VIII and King Philip IV of France, a French pope was elected to try to bring peace. That pope – Clement V – then decided to live in Avignon, France, rather than in Rome, eventually taking the entire Vatican operation with him. Over the next 67 years, seven successive popes lived in Avignon and came more and more under the control of the French crown, greatly diminishing respect for the papacy. The Great Schism – 1378-1414. Two years after Pope Gregory XI moved the papacy from Avignon back to Rome, he died and in 1378 was succeeded by an Italian – Urban VI. Soon after Urban’s election, however, the cardinals who elected him found him so difficult they left Rome and elected a different pope – Clement VII – who chose to rule from Avignon. This started the Great Schism, during which there were multiple competing claimants to the papacy. This continued until 1409, when the Council of Pisa met and deposed the two sitting popes (Benedict XIII and Gregory XII), electing a new pope in Alexander V. But the various popes refused to step down – so now there were three popes! In 1414 a new council – the Council of Constance – convinced Gregory and Alexander to step down, deposed and exiled Benedict, and elected Martin V to end the Schism – but not before most of Europe has seen the political ambition and pettiness of the Church. 4. What was the “conciliar movement” in the Church? The conciliar movement was a 14th and 15th century effort to have ecumenical councils of the Church acknowledged as the ultimate authority (over the papacy) in matters of doctrine and in times of conflict. This movement was What You Should Know From TH2-Church History 2 Page 1 especially important in trying to address the Great Schism of 1378-1414. But later councils (especially the Council of Ferrara – 1438-45) themselves caused division and confusion and so lost their perceived authority, allowing the popes to again rule the Catholic Church unchallenged. 5. Who was John Wycliffe, and why was he important? John Wycliffe (1328-1384) was an English priest, preacher and professor who lived during the time of the Avignon Papacy. During this time opposition to French influence on the Church prompted English laws limiting the pope’s authority in England, with Wycliffe contributing writings on “dominion” that claimed any ruler (including the pope) who does not act in the best interest of his subjects should be opposed. This made Wycliffe very popular in England, and his further writings established many of the ideas that would be part of the Protestant Reformation two centuries later – the importance of the Bible in native languages, rejection of transubstantiation, definition of the true Church as the elect believers (rather than the pope & hierarchy), etc. Wycliffe eventually fell out of favor because he insisted his ideas on dominion also applied to English government; the Pope issued five papal bulls against him, and some of his Oxford University colleagues declared him a heretic – but he was still allowed to write up until his death. His writings continued to have great influence (especially in Bohemia) and lay followers of his teachings, called “Lollards,” continued to preach for many years, despite being severely persecuted. 6. Who was John Huss, and why was he important? John Huss (1362-1415) was a Bohemian (Czech) professor and preacher who lived during the time of the Great Schism in the Church. Ties with Oxford University brought Wycliffe’s writing to Bohemia, where they were very influential. When Huss started preaching moral reform he got in trouble with the local archbishop (who had purchased his position), who asked the pope for help suppressing Huss. Huss refused to desist, and refused to go to Rome to answer for his disobedience, finally declaring that an unworthy pope should not be obeyed. Like Wycliffe, Huss’ ideas presaged the ideas of the Reformation by over 100 years, including the Bible as ultimate authority, the fallacy of papal indulgences, the need for God’s word to be preached freely and in the local language, communion “in both kinds,” that clergy should not be wealthy or hold public office, etc. Huss was excommunicated twice. He agreed to attend the Council of Constance under a promise of safe passage by Emperor Sigismund, but when he arrived he was arrested, tried and burned at the stake. 7. Who was Girolamo Savonarola, and why was he important? A Dominican monk who, in 1490, moved to Florence and started teaching. His teaching – especially on the incompatibility of true Christian life with a love of luxury – was very popular with common people but angered the What You Should Know From TH2-Church History 2 Page 2 wealthy. He became prior of the monastery of St. Mark and so reformed it that it became famous for scholarship, holiness and service – leading other monasteries in Italy to ask for his help. Savonarola became a great hero when he successfully interceded with a French king who threatening to sack Florence. Savonarola was known for the “bonfire of the vanities” – in which people would burn in a public bonfire those things they valued too much, as an act of contrition and discipleship. Opposition from the pope – which affected the whole city of Florence – began to turn people against Savonarola, who was taken by a mob, tortured (though he never confessed to any wrongdoing), hanged and burned. Savonarola became a model for piety and holiness against greed and love of luxury (which plagued the Church), and many even today believe he should be sainted. 8. What was the Protestant Reformation? The move to reform the doctrinal beliefs and practices of the Catholic Church which eventually led to a split in the Church and the formation of various Protestant groups, the most important of which (early on) were the Lutherans, Calvinists (or Reformed), and Anabaptists. 9. What is the accepted date for the beginning of the Protestant Reformation, and what event is seen to have started the Reformation? 1517, when Martin Luther nailed his “ninety-Five Theses” to the door of Wittenberg Cathedral, challenging the Catholic Church, especially regarding the sale of indulgences. 10. Who was Martin Luther, and why was he important? Martin Luther (1483-1546) was a monk, priest and professor of theology who was a key leader in the 16th century Protestant Reformation. While Luther was on the faculty of the University of Wittenberg in Germany, a Dominican monk named John Tetzel was sent to Germany to sell papal indulgences – with half the profits going to Leo X in Rome to help build St. Peter’s basilica; and half to go to local bishop/ruler Albert of Brandenburg. On October 31, 1517 (the date accepted as the beginning of the Protestant Reformation) Luther posted 95 theses (in the form of questions) on the door of the Wittenberg Cathedral, questioning this sale of indulgences. In 1520 Pope Leo X demanded that Luther retract his writings, but he refused. In 1521 Luther was called to appear before Emperor Charles V at the Diet of Worms, where he again was ordered to retract his writing – and again he refused. He was excommunicated and condemned as an outlaw, but on leaving Worms Luther was taken secretly to Wartburg Castle by men of Frederick the Wise of Saxony (in whose provinces Wittenberg lay). Luther stayed at Wartburg for a year, translating the New Testament into German – and in the process both giving the German people the Scripture and also creating the modern German language. What You Should Know From TH2-Church History 2 Page 3 Over the next 24 years, Luther was perhaps more responsible for the growth and development of Protestantism in Europe than any other person, fending off or side-stepping any and all attempts to stop or silence him. 11. What, in terms of the Catholic Church, is an “indulgence?” An indulgence is a grant, given by the pope or Catholic Church hierarchy, which shortens the time one is required to spend in temporal punishment in purgatory. An indulgence typically was granted in return for special services to the church or other good deeds, including (in the Middle Ages) a financial contribution to the Church. Rejection of indulgences as unbiblical was one thing that led to the Protestant Reformation. 12. Who was Ulrich Zwingli, and why was he important? Ulrich Zwingli (1484-1531) was a priest who became the leader of the 16th century Protestant reform movement in Switzerland. Many of the Reformation ideas being developed by Martin Luther in Germany occurred to and were being implemented at the same time by Zwingli in Zurich. 13. Who was John Calvin, and why was he important? John Calvin (1509-1564) was a French lawyer who fled Protestant persecution in France to become the primary theologian and religious leader of the Protestant city of Geneva. While he was of the 2 nd generation of Reformers, Calvin became unquestionably the chief systematic theologian of the Reformation, and was the founder of Reformed theology and Reformed and Presbyterian churches around the world. 14. Who were the Anabaptists, and why were they almost universally persecuted? While the ideas behind the Anabaptist movement occurred in many places, it was in Zurich that they first became organized as a church. Their key principles were an opposition to infant baptism in favor of adult believer’s baptism; extreme pacifism; absolute separation of church and state; radical egalitarianism (full equality between women and men); separation from non-Christian persons and influences; and refusal to swear oaths, serve in the military, or take any public office. More than their religious beliefs, it was the Anabaptist refusal to swear oaths of loyalty, serve in the military, or defend their countries that convinced most civil and religious authorities the Anabaptists were disloyal, untrustworthy and divisive – and that their religion therefore must be stamped out. 15. Who was responsible for establishing Protestantism in England by launching the English Reformation and founding the Church of England, and why? What You Should Know From TH2-Church History 2 Page 4 The Church of England was founded in 1534 by King Henry VIII (14911547). Henry had been a firm Catholic most of his younger life – he was even named a “Defender of the Faith” in 1521 by Pope Leo X. But when his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, did not produce a male heir, Henry requested an annulment from the pope so he could marry again. His grounds for the annulment were that Catherine had been married to Henry’s brother Arthur until Arthur’s death, and Church law forbade the marrying of your brother’s widow – even though a papal dispensation had been provided to allow Catherine and Henry to marry. Unfortunately for Henry, Catherine was the aunt of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, whom the pope did not want to offend, so no annulment was granted. Eventually Henry, in his frustration, had the English Parliament declare him the supreme head of the Church of England, that his marriage to Catherine was annulled, and that any who didn’t agree were guilty of treason. Henry went on to have six wives, with one male heir (Edward, from Jane Seymour), and two daughters – Mary Tudor from Catherine and Elizabeth from Ann Boleyn. It should be noted that Henry had no interest in Protestantism as it was developing under Luther and others – the Church of England under Henry looked exactly like the Catholic Church had in worship and structure, except that there was no longer any connection to the Pope. 16. What happened to the Church of England after Henry VIII died? Henry had arranged that he would be succeeded by his only son, Edward, followed if needed by his daughters, Mary Tudor and Elizabeth, in order of birth. Edward IV was only nine-years-old when he became king, and only lived for another six years. But even in his youth Edward insisted that Protestantism in the Church of England become “less Catholic” – with married clergy, no images in churches, communion in both kinds, and liturgy in English instead of Latin. Upon Edward’s death in 1553, his sister Mary Tudor came to the throne. As daughter of the very Catholic Catherine of Aragon, and having suffered the indignation of being made illegitimate when Henry denied Catholicism and annulled his marriage to Catherine, Mary was determined to turn England back to Catholicism and so launched an aggressive antiProtestant persecution that gained her the name “Bloody Mary.” When Mary died in 1558, Elizabeth became queen and ruled for 45 years. In that time she returned the Church of England to Protestantism, but without the more radical aspects her brother Edward had advocated. In worship, the Church of England looked very Catholic, while in theology it was Calvinist – a balance which (along with reasonable tolerance for religious differences) kept the peace as long as Elizabeth lived. 17. How did Protestantism finally become legal in the Low Countries? Before the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg were nations, they were a very diverse group of territories called the Seventeen Colonies, controlled by the Catholic Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. What You Should Know From TH2-Church History 2 Page 5 In 1555 Charles put the Provinces under his son, who later became the Spanish King Philip II. Philip was very intolerant of Protestants – especially since a great many Calvinist preachers had settled in the area and were winning converts. Philip and his sister Margaret of Parma (who served as Regent when Philip was in Spain), ruthlessly persecuted Protestants, eventually sending in an army under the Duke of Alba that executed thousands of men, women and children simply for being Protestants. William, Prince of Orange, tried to intercede but had limited success other than to drag out the conflict, and he eventually was killed by an assassin paid by Philip. But William’s 19-year-old son Maurice proved to be a better general, winning a number of battles and convincing Spain to sign a permanent truce and allow Protestantism into the area that later became the Netherlands. 18. How did Protestantism finally become legal in France? In the 16th century French King Francis I, though himself a Catholic, supported Protestants in Germany to create problems for his political rival Emperor Charles V – which meant Francis could do little to oppose Protestants (called Huguenots) in his own country. When Francis died, his sons took over in succession (Henry II, Francis II, Charles IX), with his wife Catherine de Medici being regent and powerbroker. For political reasons Catherine (who was Catholic) supported the Huguenots against her rivals, the Catholic House of Guise. In response to Catherine’s 1562 Edict of St. Germain, which gave limited freedom of worship to the Huguenots, the Guise faction began massacring unarmed Huguenots, which prompted a series of wars. But during a truce after the 1570 war, Henry Duke of Guise (for revenge) convinced Catherine and the young king to support a move against the Huguenots. So on August 24th, 1570 – St. Bartholomew’s Day – over 2000 Huguenots who had gathered in Paris for the wedding of the king’s sister were surprised and murdered in what became known as the St. Bartholomew Day Massacre. The slaughter spread through the country, but the Huguenots had a number of fortified cities so the Catholics were not able to wipe them out. The next rightful heir was Henry III – a Protestant – whom the Catholics did not want, so the Catholic Guise family produced a “document” that supposedly made Henry of Guise a direct descendant of Charlemagne and so heir to the throne. Henry of Guise marched on Paris and claimed the throne. But Henry III turned the tables, surprising and massacring Henry of Guise and his followers. In the ensuing battle Henry III fled to the camp of next-in-line-for-the-throne Henry Bourbon, but the king (Henry III) was assassinated by a fanatical monk. [NOTE that there are THREE Henrys in this story – King Henry III, Catholic Henry of Guise, and (usually) Protestant Henry Bourbon.] Henry Bourbon became Henry IV and in 1598 issued the Edict of Nantes which granted reasonable freedom of worship throughout France – which made sense, since Henry had previously changed his own religious What You Should Know From TH2-Church History 2 Page 6 affiliation FIVE times! After Henry was assassinated in 1610, his young son Louis XIII became king, with his mother Marie de Medici (and her Catholic Italian advisors) as regent. In 1622 Cardinal Richelieu effectively took over power in France, though technically he was only advisor to the king. Richelieu was politically, rather than theologically, motivated. He persecuted the Huguenots not for religious reasons, but because they possessed fortresses which Richelieu saw as a potential threat. Once the Huguenot cities were taken, Richelieu left them alone. In 1643 Louis XIV became king and – as he grew up – tried to stamp out all Protestants as dissidents, abolishing the tolerance of the Edict of Nantes and making it illegal to be a Protestant. This led to a mass exodus of Protestants from France which so impoverished the country that it may have led eventually to the French Revolution. Those Huguenots who stayed in France worshiped in secret and became known as “the Church in the Desert.” If captured, pastors were executed, men sent to galley ships as slaves, women were imprisoned for life, and children were given to Catholic families. Not until 1787 and Louis XVI was ongoing religious tolerance finally decreed in France. 19. What was the 1555 Peace of Augsburg, and what was wrong with it? The Peace of Augsburg was a treaty between Emperor Charles V (a Catholic) and Lutheran princes of Germany, allowing the princes to determine whether the people in their areas would be Catholic or Lutheran as long as they did not seek to spread Lutheranism. There were three problems with the Peace of Augsburg: i. The only Protestant option it allowed was Lutheranism, with Calvinists, Anabaptists and others still being illegal. ii. It maintained the “ecclesiastical reservation,” which said any area previously controlled by a Catholic bishop would remain Catholic, even if that bishop became Lutheran. iii. There was no way to limit the infectious spread of Protestantism, no matter what any treaty said. 20. What was the “Defenestration of Prague?” The trigger that sparked the Thirty Years War. When advisors to King Ferdinand of Bohemia refused to even listen to objections by Protestant leaders, two of the king’s advisors were thrown out a window – “defenestration.” (They fell into a pile of garbage & were not seriously hurt.) 21. What was the Thirty Years War (1618-1648)? A war that was ostensibly religious (though there were many political motivations) that devastated Germany and much of central Europe for most of the first half of the 17th Century. As the 1555 Peace of Augsburg started to break down in Germany, cities and areas started declaring for Protestantism. When the Protestant city of What You Should Know From TH2-Church History 2 Page 7 Donauworth, at the edge of Catholic Bavaria, attacked monks for parading outside their monastery, Duke Maximilian of Bavaria showed up with an army and started forcing people to convert to Catholicism. In response the Lutherans formed the Evangelical Union to prepare for war, and the Catholics did the same by forming the Catholic League (which was much larger). In Bohemia a great many German Calvinist immigrants had considerably increased the Protestant population, prompting King Ferdinand of Bohemia (who later became Emperor Ferdinand II) to make laws restricting Protestantism. When Protestants objected and the king’s advisors would not listen, two of those advisors were thrown out a window – causing the start of the Thirty Years War. The Bohemians asked Frederick, elector of the Palatinate, to become their king, and Emperor Ferdinand responded by sending a Catholic army under Maximilian of Bavaria to invade Bohemia and depose Frederick – which they did. They then passed an edict that everyone in Bohemia had to convert to Catholicism by Easter 1626 or leave the country – which (along with war casualties) led to an 80% decline in the population of Bohemia over the next 30 years. In 1625 England, Denmark and the Netherlands sided with the Evangelical Union to oppose Ferdinand, but the emperor recruited a second army and the invading Danes were forced to accept a truce and retreat. Then young Swedish king Gustavus Adolphus invaded Germany to defend the Protestants and limit the Hapsburg family’s power. After winning many battles and the hearts and support of the people, Adolphus crushed the primary Catholic army at Lutzen, but was killed in the battle. The Spanish Hapsburgs then sent an army to support their cousin Ferdinand, which caused the French to step in to help the Protestants (even though France was at that time controlled by Catholic Cardinal Richelieu). Ferdinand II died and his son Ferdinand III was much more tolerant – especially since everyone was tired of war. The 1648 Peace of Westphalia ended the Thirty Years War and gave Catholics, Lutherans and Calvinists the right to follow their conscience in religion. 22. What was the Puritan Revolution in England? The Puritan Revolution was the struggle, after the death of Elizabeth I, to reform the Church of England by making it less Catholic in worship and more Presbyterian in governance. This conflict eventually led to civil war and the execution of King Charles I. During her life Queen Elizabeth was able to balance a Church of England that looked Catholic in its worship but was Calvinist in its theology, while offering considerable religious freedom. But after her death, when James IV of Scotland (son of Mary Stuart) became James I of England, the English Calvinists (known as “Puritans”) thought the time had come to complete the reform of worship and governance in the Church of England. But James I believed his rule as king was dependent on having bishops to What You Should Know From TH2-Church History 2 Page 8 support him, so he opposed efforts to move away from an episcopal structure and towards Presbyterianism. Eventually Parliament (especially the Lower House of Commons) became more and more Puritan and more opposed to James and his bishops. Whenever James would call Parliament to get approval for new taxes or funding, Parliament would instead demand that James deal with their complaints – so James would dissolve that Parliament and try again later. When James I died he was succeeded by his son Charles I, and things got worse. Charles forced through anti-Puritan laws in England and Scotland, until finally Scotland rebelled. When Charles asked Parliament for help dealing with the Scottish rebellion, Parliament sided with the Scots – which encouraged the Scottish army to invade England. Charles asked Parliament to help fight off the invasion but they refused, instead repealing all anti-Puritan laws, freeing prisoners and passing laws limiting the king’s power over them. When it was discovered Charles had been negotiating (though his Catholic French wife) with the Catholic Irish to invade England, some in Parliament wanted to try the Queen for treason. Charles accused these accusers of treason and when Parliament would not turn them over, the king he sent troops to get them – but they were opposed by the people of London. Charles fled London and gathered his troop, while Parliament also put together an army, and the English civil war began. At this time Parliament called the Westminster Assembly of Divines – a gathering of theologians and lay people from England and Scotland – for the purpose of defining a new and Presbyterian form of church worship and government. The result was the Westminster Confession of Faith – to this day one of the foundational documents of Reformed Calvinism. In response to the call to war, Puritan member of Parliament Oliver Cromwell returned to his home and raised a corps of cavalry to oppose the king’s cavalry, and his men’s spirituality and dedication inspired the entire Parliamentary army. Cromwell’s forces crushed the king’s army at Naseby, and in the king’s camp they found documentation proving Charles had been encouraging foreign powers to invade England. When Charles later tried to negotiate support from the Scottish he was captured and turned over to Parliament. There was, however, a division between Parliament, made up mostly of Puritans who wanted a national church (the “Presbyterians”); and the army, most of whom wanted each church to be self-governing (the “Independents”). Parliament tried in 1646 to disband the army, but instead Cromwell and the army decided they better represent the people. Meanwhile King Charles had escaped and finally gained support in the Scottish army, but Cromwell’s forces defeated the Scots. The king was recaptured, then tried for treason and, on January 30, 1649, he was beheaded. With chaos threatening, Cromwell took over as Lord Protector, sending a weak and self-serving Parliament home. He served in this role until his What You Should Know From TH2-Church History 2 Page 9 death in 1658, quelling violence and rebellions in the kingdom and trying to reform both church and state. After Cromwell’s death Parliament recalled the son of Charles I – Charles II – to be king. Charles II reestablished the episcopal Church of England and tried to force the same model on Presbyterian Scotland, with little success. When Charles died, his brother and successor James II tried to restore Catholicism in Britain, but after three years England rebelled, James fled to France, and his daughter Mary and her husband William of Orange were invited to become king and queen of England. They accepted, and reestablished the Church of England and religious tolerance as it had existed under Elizabeth I. 23. What was the Catholic Reformation and Counter-Reformation? The Catholic Reformation was an effort, which had gone on for many years before Martin Luther, which attempted to reform the Catholic Church by dealing with many of the moral problems within the Church – including simony (purchasing church positions), nepotism (placing relatives in church positions), pluralism (bishops holding multiple positions), absenteeism (bishops holding and getting income from bishoprics without actually being there), and lack of discipline in monasteries. Among other things, the Catholic Reformation led to the creation of new monastic orders, including the Jesuits under Ignatius Loyola, and the Discalced Carmelites under Teresa of Avila. The Counter-Reformation was a comprehensive (though late) response by the Catholic Church to the Protestant Reformation, in an attempt to respond to and provide polemics against Protestant doctrinal claims. In essence the Counter-Reformation gave a single focus to all Catholic efforts at reform by making the Protestants the target. The Council of Trent (1545-1563) was the pinnacle of Catholic Reformation and CounterReformation efforts. 24. What was the Council of Trent, and why was it important? The Council of Trent (1545-1563) was the Catholic response to the Protestant Reformation by attempting to respond to all of the doctrinal and ecclesiastical challenges that had been presented by Luther and others of the Protestant Reformers. Included among the many declarations of the Council of Trent was an affirmation of the Latin Vulgate as authoritative; that Church tradition was equal to Scripture in authority; that there are seven holy sacraments; that the Mass is a sacrifice that can be offered for the benefit of the deceased; that communion in both kinds is not necessary; that justification requires good works as well as grace; and much more. (In effect, going against virtually EVERYTHING the Protestant Reformers had been saying.) The Council of Trent was the pinnacle of Catholic Counter-Reformation efforts, establishing standards of Catholic orthodoxy for the next 400 years, and – in effect – creating the modern Catholic Church. What You Should Know From TH2-Church History 2 Page 10