Periodontics

advertisement

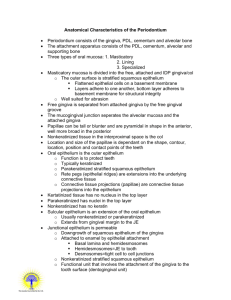

Periodontics DENTALELLE TUTORING The Periodontium AB, alveolar bone; AC, alveolatrcrest; AM, alveolar mucosa; AP, alveolar process; CB, compact bone of alveolar bone proper; CEJ, cemento-enamel junction; CT, connective tissue; DEJ, dentino-enamel junction; ES, enamel space; G, gingiva; GE, gingival epithelium; GG, gingival groove; GM, gingival margin; GS, gingival sulcus; JE, junctional epithelium; MGJ, mucogingival junction; MS, marrow space; OE, oral epithelium; PDL, periodontal ligament; RCE, radicular (root) cementum; SE, sulcular epithelium; Incisor AB, alveolar bone; C, incisive canal; CE, cementum; F, foramen; G, gingiva; MGJ, mucogingival junction; PDL, periodontal ligament Periodontium Composed of: Gingiva Cementum Alveolar Bone Periodontal Ligament Gingiva The gingiva is the keratinized mucosa that surrounds the teeth. It forms a collar around each tooth, that ranges in width from1 to 9 mm. The narrowest zone of the gingiva is usually found on the buccal surface of the mandibular canine to first premolar region. The widest zone is often located on the lingual aspect of the last mandibular molar. The gingiva is attached in part to the cementum of the tooth and in part to the alveolar process. The gingiva is composed of masticatory mucosa. Features In light-skinned individuals the gingiva can be readily distinguished from the adjacent dark red alveolar mucosa by its lighter pink color. Its apical border, that separates it from the adjacent alveolar mucosa, is the mucogingival junction. A similar tissue relationship can be seen on the lingual aspect of the mandible. In dark-skinned persons the gingiva may contain melanin pigment to a greater extent than the adjacent alveolar mucosa. The melanin pigment is synthesized in specialized cells, the melanocytes, located in the basal layer of the epithelium. The melanin is produced as granules, themelanosomes, that are stored within the cytoplasm of the melanocytes, as well as the cytoplasm of adjacent keratinocytes. Melanocytes are embryologically derived from neural crest cells that eventually migrate into the epithelium. If pigmented gingiva is surgically resected, it will often heal with little or no pigmentation. Therefore, surgical procedures should be designed so as to preserve the pigmented tissues. The Gingiva The most coronal portion of the gingiva is the gingival margin. The term marginal gingiva refers to that portion of the gingiva that is located close to the gingival margin. The gingival sulcus is the shallow groove between the marginal gingiva and the tooth. The gingival groove is an indentation that parallels the oral or vestibular surface of the gingival margin. It is located at about the same level as the apical border of the junctional epithelium. Note: its level does not correspond to that of the bottom of the gingival sulcus. It is only present occasionally. Its presence or absence is not related to gingival health. Inflammation may cause the tissues to swell and mask its presence. Free and Attached Clinicians sometime use the terms "free" and "attached" gingiva. Although these terms may have some clinical relevance, they are anatomically incorrect. The determination as to whether the gingiva is "free" or "attached" is made by probing the gingival sulcus with a periodontal probe. This instrument will frequently penetrate the junctional epithelium beyond the sulcus bottom, particularly in the presence of inflammation. This results in the clinical impression that the marginal gingiva is detached from the tooth to a much greater degree than is the case. Anatomically. "Attached" gingiva refers to the portion of the gingiva apical to the "free" gingiva which is firmly bound to the underlying tooth and alveolar process. Parts of the Gingiva Interdental The gingiva that occupies the interdental spaces coronal to the alveolar crest is the interdental gingiva. It is composed of a pyramidal interdental papilla in the incisor region. In the posterior region it is composed of an oral and a vestibular papilla (P) joined by an interdental "col" (C). The interdental gingiva is attached to the tooth by junctional epithelium (JE) coronally and by connective tissue fibers apically (not shown). The most coronal portion of the interdental gingiva is lined with sulcular epithelium (SE) Oral Epithelium It is the stratified, squamous keratinizing epithelium, that lines the vestibular and oral surfaces of the gingiva. It extends from the mucogingival junction to the gingival margin, except for the palatal surface where it blends with the palatal epithelium. The oral epithelium consists of a basal layer (stratum basale, SB), a spinous layer (stratum spinosum, SS), a granular layer (stratum granulosum, SG) and a cornified layer (stratum corneum, SC). It is designed primarily for protection against mechanical injury during mastication. Resistance to mechanical injury is mediated primarily by the numerous intercellular junctions, mostly desmosomes, that hold the cells tightly together and the cornified layer. The cornified layer and the relatively narrow intercellular spaces also contribute to the relative lack of permeability. The oral epithelium is connected to the underlying connective tissue of the lamina propria by an irregular interface. This interface consists of finger-like projections of connective tissue from the papillary layer extending into depressions on the undersurface of the epithelium. These depressions are located between the interconnected Rete ridges that form the undersurface of the epithelium. Crosssections of these ridges, as seen in histological sections are sometimes referred to as Rete pegs. Transmission electron micrograph of the junction between a basal cell of the gingival oral epithelium and the connective tissue of the underlying lamina propria. The epithelial cell (EC) contains widely dispersed cytoplasmic filaments, also known as tonofilaments. The epithelial cell membrane facing the lamina propria is studded with numerous hemidesmosomes (HD) and is connected to it by a basal lamina(BL). The basal lamina consists of an electron-dense layer, the lamina densa (LD) and an electron-lucent layer, the lamina lucida (LL). The lamina densa is composed of an afibrillar type of collagen, type IV collagen. The lamina lucida is composed of laminin and other glycoproteins. Anchoring fibrils (AF), composed of type VII collagen, extend from the undersurface of the lamina densa into the lamina propria. Sulcular Epithelium It is the stratified, squamous epithelium, non-keratinized or para keratinized, that is continuous with the oral epithelium and lines the lateral surface of the sulcus. Apically, it overlaps the coronal border of the junctional epithelium, a structural design that minimizes ulceration of the epithelial lining in this region. This epithelium shares many of the characteristics of the oral epithelium (Fig. 10), including good resistance to mechanical forces and relative impermeability to fluid and cells. The overall structure of the sulcular epithelium resembles that of the oral epithelium, except for the surface layer that is less keratinized than its counterpart in the oral epithelium. This incomplete type of keratinization is referred to as parakeratinization. CT, gingival connective tissue; GS, gingival sulcus; PKE, parakeratinized epithelial layer. Junctional Epithelium It is the stratified non-keratinizing epithelium, that surrounds the tooth like a collar with a cross-section resembling a thin wedge. It is attached by one broad surface to the tooth and by the other to the gingival connective tissue. The junctional epithelium has 2 basal laminas, one that faces the tooth (internal basal lamina) and one that faces the connective tissue (external basal lamina). The proliferative cell layer responsible for most cell divisions is located in contact with the connective tissue, i.e. next to the external basal lamina. The desquamative (shedding) surface of the junctional epithelium is located at its coronal end, which also forms the bottom of the gingival sulcus. The junctional epithelium is more permeable than the oral or sulcular epithelium. It serves as the preferential route for the passage of bacterial products from the sulcus into the connective tissue and for fluid and cells from the connective tissue into the sulcus. The term epithelial attachment: refers to the attachment apparatus, i.e. the internal basal lamina and hemidesmosomes, that connects the junctional epithelium to the tooth surface. This term is not synonymous with junctional epithelium which refers to the entire epithelium. Segment of junctional epithelium (JE) from an area just apical to the gingival sulcus. The width of the junctional epithelium may consist of as many as 30 cells in the sulcus region to as few as one cell in its most apical portion. The intercellular spaces between the cells of the junctional epithelium are wider than in the oral or sulcular epithelia. This is due in part to the lower density of intercellular junctions between the cells of the junctional epithelium. The density of junctions is approximately one third of that in the oral and sulcular epithelium. This section is unusual by the absence of inflammatory cells in the connective tissue adjacent to the epithelium. Transmission electronmicrograph of normal, uninflamed junctional epithelium (JE). The cells are orientated with their long axis parallel to the tooth surface. The intercellular spaces are relatively narrow. The epithelium is attached to the enamel by an internal basal lamina (IBL) and to the connective tissue (CT) by the external basal lamina (EBL). ES, enamel space. The cytoplasm of the junctional epithelium contain dispersed tonofilaments, but lack tonofibrils. Under normal circumstances these cells do not undergo keratinization. Transmission electronmicrograph of junctional epithelium in inflamed gingiva. Note the marked distension of the intercellular spaces by polymorphonuclear leucocytes (PMN) that are migrating from the connective tissue toward the gingival sulcus (located toward the top of the micrograph). Fluid exudate from the connective tissue also flows into the sulcus through the enlarged intercellular spaces. The spaces enlarge in part through rupture of the desmosomal junctions and in part because they become distended by inflammatory cells and fluid. The bi-directional arrows indicate that the junctional epithelium (JE) is the most permeable portion of the gingival epithelia. Soluble substances can diffuse from the oral cavity into the underlying gingival connective tissue (CT), while both fluids and cells can travel through the junctional epithelium from the connective tissue into the gingival sulcus (S) on their way to the oral cavity. Because of its permeability to bacterial products and other assorted antigens originating in the oral cavity, the connective tissue adjacent to the junctional epithelium tends to become infiltrated with chronic inflammatory cells, primarily lymphocytes and plasma cells. OE, oral epithelium; SE, sulcular epithelium. Gingival Connective Tissue The gingival connective tissue is composed of gingival fibers, ground substance, and cells, including neural and vascular elements. The bulk of the gingival connective tissue is composed of a dense, predominantly collagenous matrix that contains collagen fibers running in recognized fiber groups. These are referred to as the principal fibers of the gingival connective tissue. The dense gingival connective tissue is referred to as a lamina propria. It consists of the papillary layer, finger-like projections of connective tissue that are contained within depressions on the undersurface of the overlying epithelium, and the reticular layer, located between the epithelial undersurface and the root surface or adjacent alveolar process. At its junction with the lining mucosa, in the region delineated by the mucogingival junction, the lamina propria becomes continuous with the much looser and elastic connective tissue of the alveolar submucosa. The major components of the gingival connective tissue include the fibers, the ground substance or intercellular matrix, assorted cells, blood and lymphatic vessels, and nerves. The ground substance occupies the space between cells, fibers and neurovascular elements. Its major constituents are water, glycoproteins and proteoglycans. The ground substance permits the diffusion of biological substances between various structural elements. Gingival Fibers Most of the fibers are composed of collagen, with minor contributions from elastic fibers and oxytalan fibers. Elastic and oxytalan fibers are generally confined to perivascular regions, although oxytalan fibers are also found as thin fiber bundles within collagen-rich regions like the lamina propria. Gingival Fibers - Collagen Transmission electron micrograph of gingival connective tissue showing the intercellular junctions (ICJ) between cytoplasmic strands from adjacent fibroblasts. The fibroblasts form an interconnected network of cells, the intercellular spaces of which are filled with fibers and ground substance, the jelly-like material in which the fibers are embedded. The fibroblasts are responsible for the production of the fibers and ground substance. They are also capable of removing fibers and ground substance during remodeling of the gingival tissues. Most of the fibers in gingival connective tissue are composed of collagen. The bulk of the collagen is type I collagen, the most abundant form of collagen in the human body. The structural unit of type I collagen is a typically striated fibril with a characteristic banding pattern that repeats every 64 nm. The banding results from the packing arrangement of the collagen molecules that make up the individual fibril Fibrils Type I collagen fibrils are normally organized into bundles of fibrils, or fibers. They are found throughout the lamina propria. Type III collagen fibers are thinner than the type I fibers and tend to be found close to basal laminas of vascular channels and epithelial tissues. They stain readily with silver stains and probably account for most of the argyrophilic (silver stained) fibers seen in silver-stained sections. They are also known as reticular fibers. Gingival Fibers - Other Type VII collagen is found as anchoring fibrils, located in intimate contact with epithelial basal laminas. In addition to the fibrillar forms of collagen mentioned above, type IV collagen, an amorphous form of collagen, is found in the basal laminas of the epithelial lining and blood vessel walls, primarily in the lamina densa. The other fiber types found in the periodontium are elastic fibers and oxytalan fibers. Elastic fibers are rather scarce in the lamina propria. They are a more common constituent of the lining submucosa. They consist of 2 major components, microfibrils made of fibrillin and the amorphous component elastin. The latter provides the fiber with its elastic properties. Note that elastic fibers consist of 2 distinct structural entities, a microfibrillar component (MF) composed of the protein fibrillin, and an amorphous component (AE) that is composed of elastin, the protein that gives the fibers their elastic properties. As elastic fibers mature, the ratio of elastin to fibrillin increases. In the gingiva, most elastic fibers are immature and poorly developed. Oxytalan fibers are a fiber type related to elastic fibers. They appear to consist of the microfibrillar component only, thereby resembling very immature elastic fibers. Fiber Groups These are largely composed of collagenous fibers. The dentogingival fibers (A) insert into the supracrestal root cementum and fan out into the adjacent connective tissue. The dentoperiosteal fibers (B) insert into the supracrestal root cementum and blend with the periosteal covering of the adjacent alveolar process. The alveologingival fibers (C) insert into the alveolar crest and fan out into the adjacent gingival connective tissue. The circumferential fibers (D) follow a circular course around individual dental units. The semicircular fibers (E) insert on the approximal surfaces of a tooth and follow a semicircular course to insert on the opposite side of the same tooth. The transgingival fibers (F) insert into the approximal surface of a tooth and fan out toward the oral or vestibular surface. The intergingival (G) fibers course along the oral or vestibular surfaces of the dental arch. The transseptal fibers (H) course from one approximal tooth surface to the approximal surface of the adjacent tooth. Gingival Cells The major cellular elements in the gingival connective tissue include: Fibroblasts, macrophages, mast cells, osteoblasts and osteoblast precursor cells, cementoblasts and cementoblast precursor cells, osteoclasts and odontoclasts, assorted inflammatory cells, and cells that make up vascular channels and nerves. Inflammatory cells include polymorphonuclear leucocytes, lymphocytes and plasma cells. Under normal circumstances they may be found in small numbers, as isolated cells. In the presence of inflammation they can be found in large numbers, often as dense cellular aggregates that have replaced the fibrous elements in the connective tissue. The connective tissue also contains undifferentiated ectomesenchymal cells that serve as a replacement source for more differentiated cells, primarily fibroblasts. Fibroblasts are irregularly shaped cells responsible for the synthesis of various connective tissue fibers and the ground substance in which they are imbedded. They are also responsible for the removal of these structural elements. Therefore these cells play a key role in the maintenance and remodeling of the connective tissue. Vessels and Nerves (i) Blood supply: The gingival blood supply originates from blood vessels in the periodontal ligament, the marrow spaces of the alveolar process and supraperiosteal blood vessels. These vessels in turn supply major capillary plexuses that are located in the connective tissue adjacent to the oral epithelium and the junctional epithelium. (ii) Lymphatics: The gingival tissues are supplied with lymphatic vessels that drain principally to submaxillary lymph nodes. (iii) Nerves: Branches of the trigeminal nerve provide sensory and proprioceptive functions. In addition, autonomic nerve endings are associated with the vasculature. Connective Tissue – Epithelial Interactions The interaction of connective tissues and adjacent epithelia have a significant effect on epithelial tissue differentiation. The dense lamina propria found under the masticatory mucosa is largely responsible for the maintenance of the stratified squamous keratinizing epithelium that covers it. Likewise, the loose connective tissue that supports the non-keratinizing lining epithelium is largely responsible for the absence of keratinization in this epithelium. If a tissue graft consisting of lamina propria is taken from the masticatory mucosa of the hard palate and is transplanted to a region lacking an adequate covering of keratinizing mucosa, it will induce the epithelium that grows over it to keratinize, even if the epithelium originates from an adjacent, non-keratinized mucosal surface. This property of the connective tissue to modulate the differentiation of the overlying epithelium is taken advantage of in reconstructive surgical procedures. For example, a palatal connective tissue graft can be transplanted subepithelially to a zone lacking keratinized mucosa, where it will induce the overlying epithelium to differentiate into a keratinized epithelium. Periodontal Ligament Supportive The periodontal ligament serves primarily a supportive function by attaching the tooth to the surrounding alveolar bone proper. This function is mediated primarily by the principal fibers of the periodontal ligament that form a strong fibrous union between the root cementum and the bone. The periodontal ligament also serves as a shock-absorber by mechanisms that provide resistance to light as well as heavy forces. Light forces are cushioned by intravascular fluid that is forced out of the blood vessels. Moderate forces are also absorbed by extravascular tissue fluid that is forced out of the periodontal ligament space into the adjacent marrow spaces. The heavier forces are taken up by the principal fibers. Remodeling The periodontal ligament also serves a major remodeling function by providing cells that are able to form as well as resorb all the tissues that make up the attachment apparatus, i.e. bone, cementum and the periodontal ligament Undifferentiated ectomesenchymal cells, located around blood vessels, can differentiate into the specialized cells that form bone (osteoblasts), cementum (cementoblasts), and connective tissue fibers (fibroblasts). Bone- and tooth-resorbing cells (osteoclasts and odontoclasts) are generally multinucleated cells derived from blood-borne macrophages. Sensory and Nutritive The periodontal ligament also serves a sensory function. The myelinated dental nerves that perforate the fundus of the alveoli rapidly lose their myelinated sheath as they branch to supply both the pulp and periodontal ligament. The periodontal ligament is richly supplied with nerve endings that are primarily receptors for pain and pressure. Finally, the periodontal ligament provides a nutritive function that maintains the vitality of its various cells. The ligament is well-vascularized, with the major blood supply originating from the dental arteries that enter the ligament through the fundus of the alveoli. Major anastomoses exist between blood vessels in the adjacent marrow spaces and the gingiva. Cementum Cementum Cementum may be found both on the root as well as the crowns of teeth. It may also vary in its structure. Some forms of cementum may be cellular, while others are not. Some have a fibrillar collagenous matrix, while others do not. Cementum may be classified in the following ways: Radicular cementum: The cementum that is found on the root surface. Coronal cementum: The cementum that forms on the enamel covering the crown. Cellular cementum: Cementum containing cementocytes in lacunae within the cementum matrix. Acellular cementum: Cementum without any cells in its matrix. Fibrillar cementum: Cementum with a matrix that contains well-defined fibrils of type I collagen. Afibrillar cementum: Cementum that has a matrix devoid of detectable type I collagen fibrils. Instead, the matrix tends to have a fine, granular consistency. Extrinsic fiber cementum: Cementum that contains primarily extrinsic fibers, i.e. Sharpey's fibers that are continuous with the principal fibers of the periodontal ligament. Since the fibers were originally produced by periodontal ligament fibroblasts, they are considered "extrinsic" to the cementum. These fibers are orientated more or less perpendicularly to the cementum surface and play a major role in tooth anchorage. Intrinsic fiber cementum: Cementum that contains primarily intrinsic fibers, i.e. fibers produced by cementoblasts and that are orientated more or less parallel to the cementum surface. This form of cementum is located predominantly at sites undergoing repair, following surface resorption. It plays no role in tooth anchorage. Mixed fiber cementum: Cementum that contains a mixture of extrinsic and intrinsic fiber cementum. Types 1. Acellular, afibrillar cementum This cementum is mostly composed of mineralized matrix, without detectable collagen fibrils or cementocytes. It is produced exclusively by cementoblasts. It is typically found as coronal cementum on human teeth. 2. Acellular, extrinsic fiber cementum This type of cementum has a matrix of well-defined, type I collagen fibrils. The fibrils are part of the, densely packed Sharpey's fibers, that are continuous with the principal fibers of the periodontal ligament. Because of their dense packing, the individual Sharpey's fibers that form the bulk of the matrix may no longer be identifiable as individual fibers within the cementum layer. This cementum, which is acellular, is located in the cervical two-thirds of the root of human teeth. It plays a major role in tooth anchorage. 3. Cellular, intrinsic fiber cementum This cementum contains cementocytes in a matrix composed almost exclusively of intrinsic fiber cementum. It is located almost exclusively at sites of cementum repair. It plays no part in tooth anchorage. However, it may be covered over by extrinsic or mixed fiber cementum, both of which are able to provide new anchorage. 4. Cellular, mixed fiber cementum It is found on the apical third of the root and in furcations (i.e. between roots). In these locations, the rate of cementum formation is usually more rapid than in the cervical region. The mineralized, extrinsic collagen fibers (Sharpey's fibers) run a more irregular course than in acellular, extrinsic fiber cementum. Intrinsic fibers are found interspersed among the extrinsic fibers of the cementum matrix, so that individual Sharpey’s fibers are more readily identifiable than in extrinsic fiber cementum. Cementoblasts are trapped in hollow chambers (or lacunae) where they become cementocytes. The thickness of radicular cementum increases with age. It is thicker apically than cervically. Thickness may range from 0.05 to 0.6 mm. Bone General The alveolar process is the portion of the jawbone that contains the teeth and the alveoli in which they are suspended. The alveolar process rests on basal bone. Proper development of the alveolar process is dependent on tooth eruption and its maintenance on tooth retention. When teeth fail to develop (e.g. anodontia), the alveolar process fails to form. When all teeth are extracted, most of the alveolar process becomes involuted, leaving basal bone as the major constituent of the jawbone. The remaining jawbone, therefore, is much reduced in height. The alveolar process is composed of an outer and inner cortical plate of compact bone that enclose the spongiosa, a compartment composed of spongy bone ( also called trabecular or cancellous bone). It is important to distinguish between the terms "alveolar process" and "alveolar bone" . Alveolar Bone/Alveolar Process The alveolar bone proper lines the alveolus (or tooth housing) which is contained within the alveolar process. It is composed of a thin plate of cortical bone with numerous perforations ( or cribriform plate) that allow the passage of blood vessels between the bone marrow spaces and the periodontal ligament. The coronal rim of the alveolar bone forms the alveolar crest, which generally parallels the cementoenamel junction at a distance of 1-2 mm apical to it Fenestration Where roots are prominent and the overlying bone very thin, the bone may actually resorb locally, creating a window in the bone through which the root can be seen. This window-like defect in the bone is referred to as a fenestration (F) Dehiscence In some cases, as shown in this figure, the rim of bone between the fenestration and the alveolar crest may disappear altogether and produce a defect known as a dehiscence (D). Awareness of these defects is important when surgical flaps are reflected, as the exposure of such defects during surgery may aggravate their severity. Bone Formation Bone is produced by osteoblasts (OB) that are found in the periosteum, endosteum and periodontal ligament adjacent to bone-forming surfaces. These specialized cells originate from less differentiated precursor cells close to the bone. These cells are in turn derived from undifferentiated ectomesenchymal cells found in the periosteum, endosteum and the periodontal ligament. During bone formation, osteoblasts become incorporated into bone as osteocytes (OC) that are completely surrounded by bone. The chamber in which they are trapped is called a lacuna (plur. lacunae). Osteocytes remain connected to osteoblasts and other osteocytes by cytoplasmic processes that run through small canals in the bone, or canaliculi (C). Osteon Cortical plate of compact bone in the mandible. The mandible is enveloped by a well-developed cortex of compact bone. The bulk of the compact bone consists of cylindrical units of bone, the osteons or Haversian systems (HS). Each osteon has a central canal, the Haversian canal that houses a blood vessel. Haversian canals are linked to one another and the periphery of the cortex by Volkman canals that course perpendicularly to the Haversian canals. The outer and inner layers of the cortex consist of parallel lamellae of compact bone, called the external (ECL) and internal circumferential lamellae. The bone that fills the spaces between adjacent osteons is the interstitial bone. CLASSIFICATION OF PERIODONTAL DISEASES Gingival Diseases… Gingival Diseases Dental plaque-induced gingival diseases* 1. Gingivitis associated with dental plaque only a. without other local contributing factors b. with local contributing factors (See VIII A) Systemic Factors Gingival diseases modified by systemic factors a. associated with the endocrine system 1) puberty-associated gingivitis 2) menstrual cycle-associated gingivitis 3) pregnancy-associated a) gingivitis b) pyogenic granuloma 4) diabetes mellitus-associated gingivitis b. associated with blood dyscrasias 1) leukemia-associated gingivitis 2) other Medications Gingival diseases modified by medications a. drug-influenced gingival diseases 1) drug-influenced gingival enlargements 2) drug-influenced gingivitis a) oral contraceptive-associated gingivitis b) other Malnutrition Gingival diseases modified by malnutrition a. ascorbic acid-deficiency gingivitis b. other Non-plaque induced 1. Gingival diseases of specific bacterial origin a. Neisseria gonorrhea-associated lesions b. Treponema pallidum-associated lesions c. streptococcal species-associated lesions d. other Viral Origin Gingival diseases of viral origin a. herpesvirus infections 1) primary herpetic gingivostomatitis 2) recurrent oral herpes 3) varicella-zoster infections b. other Fungal Origin Gingival diseases of fungal origin a. Candida-species infections 1) generalized gingival candidiasis b. linear gingival erythema c. histoplasmosis d. other Genetic Origin Gingival lesions of genetic origin a. hereditary gingival fibromatosis b. other Systemic Conditions a. mucocutaneous disorders 1) lichen planus 2) pemphigoid 3) pemphigus vulgaris 4) erythema multiforme 5) lupus erythematosus 6) drug-induced 7) other Continued b. allergic reactions 1) dental restorative materials a) mercury b) nickel c) acrylic d) other 2) reactions attributable to a) toothpastes/dentifrices b) mouth rinses/mouthwashes c) chewing gum additives d) foods and additives 3) other Traumatic and Foreign Traumatic lesions (factitious, iatrogenic, accidental) a. chemical injury b. physical injury c. thermal injury 7. Foreign body reactions 8. Not otherwise specified (NOS) Periodontal Diseases… Chronic and Aggressive Chronic Periodontitis† A. Localized B. Generalized III. Aggressive Periodontitis† A. Localized B. Generalized Perio - Systemic Periodontitis as a Manifestation of Systemic Diseases A. Associated with hematological disorders 1. Acquired neutropenia 2. Leukemia's 3. Other Continued B. Associated with genetic disorders 1. Familial and cyclic neutropenia 2 Down syndrome 3. Leukocyte adhesion deficiency syndromes 4. Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome 5. Chediak-Higashi syndrome 6. Histiocytosis syndromes 7. Glycogen storage disease 8. Infantile genetic agranulocytosis 9. Cohen syndrome 10. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (Types IV and VIII) 11. Hypophosphatasia 12. Other C. Not otherwise specified (NOS) Necrotizing Necrotizing Periodontal Diseases A. Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (NUG) B. Necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis (NUP) VI. Abscesses of the Periodontium A. Gingival abscess B. Periodontal abscess C. Pericoronal abscess VII. Periodontitis Associated With Endodontic Lesions A. Combined periodontics-endodontic lesions Developmental or Acquired VIII. Developmental or Acquired Deformities and Conditions A. Localized tooth-related factors that modify or predispose to plaque-induced gingival diseases/periodontitis 1. Tooth anatomic factors 2. Dental restorations/appliances 3. Root fractures 4. Cervical root resorption and cemental tears Continued Mucogingival deformities and conditions around teeth 1. Gingival/soft tissue recession a. facial or lingual surfaces b. interproximal (papillary) 2. Lack of keratinized gingiva 3. Decreased vestibular depth 4. Aberrant frenum/muscle position 5. Gingival excess a. pseudo pocket b. inconsistent gingival margin c. excessive gingival display d. gingival enlargement (See I.A.3. and I.B.4.) 6. Abnormal color Continued C. Mucogingival deformities and conditions on edentulous ridges 1. Vertical and/or horizontal ridge deficiency 2. Lack of gingiva/keratinized tissue 3. Gingival/soft tissue enlargement 4. Aberrant frenum/muscle position 5. Decreased vestibular depth 6. Abnormal color D. Occlusal trauma 1. Primary occlusal trauma 2. Secondary occlusal trauma Please Remember… Can be further classified on the basis of extent and severity. As a general guide… Extent can be characterized as Localized = ≤30% of sites involved and Generalized = >30% of sites involved. Severity can be characterized on the basis of the amount of clinical attachment loss (CAL) as follows: Slight = 1 or 2 mm CAL, Moderate = 3 or 4 mm CAL, and Severe = ≥5 mm CAL. The Gingival Index The Gingival Index, published by Löe in 1967, scores a 0 for no visible signs of inflammation a 1 for slight change in color and texture, a 2 for noticeable inflammation and bleeding upon probing and a 3 for overt inflammation and spontaneous bleeding. The Plaque Index, published by Silness & Löe in 1964, scores plaque deposits on a 0-3 scale where 0 indicates that plaque is absent, 1 indicates plaque detected by gingival marginal probing, 2 indicates visible plaque and 3 indicates a lot of plaque. Inflammation The presence or absence of inflammation have been clinically assessed by gingival redness, suppuration, bleeding on probing (BOP), measurements of gingival temperature and gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) and supragingival plaque. Further measures of success include maintaining and improving periodontal comfort, esthetics and function. Current Health is Important The patient’s current, and historic periodontal health and plaque control status serves as a baseline when setting goals. The presence, absence, history, extent and severity of periodontal diseases indicate the need for various therapies. ORA The Oral Risk Assessment (ORA) and Early Intervention System provide a methodology to organize patient “CARE”: • Collection of relevant medical and dental information • Assessment and assimilation of the collected information • Recommendation of professional therapies and home care procedures and products • Evaluation of treatment and healthcare outcomes Health Implications The patient’s current systemic health also impacts the setting of periodontal health goals. Systemic conditions, infections, anomalies, trauma, etc. contribute to gingival and periodontal diseases. For example, diabetes, endocrine effects, medications, malnutrition, hematologic disorders, genetic disorders as well as other systemic considerations may affect oral health. Remember the Anatomy The alveolar process is the portion of the mandible and the maxilla that supports the teeth. Tooth attachment is attained by the alveolar bone, the root cementum and the periodontal membrane. Compact bone lines the alveolus, or tooth socket, and is seen radiographically as the lamina dura. Cancellous bone, containing bone trabeculae, is found between the tooth sockets. The Bone The Bone Bone is often thought to be a static structure, but it actually is continuously remodeling through actions of osteoclasts (bone resorbing cells) and osteoblasts (bone-building cells) and their products, under the influence of parathyroid hormone (PTH), vitamin D, estrogens, glucocorticoids, growth hormone, thyroid hormone and other factors such as cytokines, a unique family of growth factors. Remodeling the Bone Remodeling is accomplished in the trabecular bone of the alveolar process, and elsewhere, by a team of cells that dissolves a pit-like area in bone and then fills it with new bone. This team of cells is called the Basic Multicellular Unit (BMU). Bone is remodeled through a sequence of steps that may take as much as 200 days, as follows: Origination Origination is the phase during which a BMU originates following an initiating “event” such as micro damage, mechanical stress, exposure to one or more of a group of biological factors, or even at random. The immune response begins in reaction to one of these events. Cytokines and other growth factors, such as parathyroid hormone (PTH), insulin-like growth factors (IGF), interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF), are important in the Origination phase. Continued IL-1 may be the most important factor in the immune response. Its function is to enhance the activation of Tcells in response to antigen. IL-6 is produced by fibroblasts and other cells. IL-6 enhances glucocorticoid syntheses. Overall it augments the response of immune cells to other cytokines. Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF- α), like IL-1, is a major immune response-modifying cytokine produced mainly by activated macrophages. The presence of TNF induces osteoclast formation. Factors such as estrogen can reduce occurrence of the Origination phase, thereby reducing the rate and occurrence of bone resorption. Biologically mediated strategies for improving bone growth in periodontitis patients work to modify the effects of factors that promote bone resorption or to boost the effects of the factors that promote bone growth. Osteoclast Recruitment The lining cells that were activated during Origination secrete RANK-ligand, which may remain bound to the cell surface. Preosteoclasts are activated by RANK-ligand (RANKL) and then differentiate into mature osteoclasts which develop a ruffled border and resorb bone. Osteoprotegerin (OPG) can act to bind the RANK-ligand which reduces its effect. RANK-ligand is a potent bonebuilding agent. Osteoclasts are more effective at resorbing bone when RANK-ligand’s effect is reduced. Resorption Bone is resorbed by the mature osteoclasts for approximately two weeks at a given location until the osteoclasts undergo preprogrammed cell death. New osteoclasts are continuously activated as the BMU travels. Integrins and interleukins are immune factors that can act to increase osteoclast activity. Integrins are cell surface receptors that bind ligands and reduce their bone-building effect. Estrogen, calcitonin, interferon and TGF can reduce bone resorption during this phase. Calcitonin works in opposition to parathyroid hormone and can reduce its role in bone resorption. Similarly bisphosphonates, such as risedronate sodium inhibit osteoclast mediated bone resorption thereby reducing net bone loss. Osteoblast Recruitment Osteoblasts are derived from bone marrow stromal cells and are attracted by bone-derived growth factors, (including Cbfa1, BMP’s, IGF, PTH, and others) and perhaps the remains of the selfdestructed osteoclasts. Cbfa1 activates the bonespecific protein, osteocalcin. Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) induce new bone formation by stimulating proliferation and migration of undifferentiated bone cell precursors. Osteoid Formation and Mineralization Osteoblasts start the process of bone-building by secreting layers of osteoid to slowly refill the cavity, as well as growth factors (including TGF-beta, BMP’s and IGF) and proteins. The presence of glucocorticoids may retard osteoid formation. Mineralization The osteoid begins to mineralize utilizing calcium and phosphate when it is approximately 6 microns thick. Mineralization is controlled by osteoblast activity. The presence of pyrophosphate may reduce mineralization. Mineral Maturation Bone density increases over months after the cavity has been filled with bone because the mineral crystals become more closely packed. Quiescence During quiescence, some osteoblasts become lining cells which help regulate ongoing calcium release from the bones. Other osteoblasts become osteocytes which remain in bone, connected by long cell processes, which can sense functional stress on the bone. Bone Loss based on Morphology Bone lost to chronic periodontitis can create bone defects with varying characteristics. For example, intra bony defects can have 1, 2 or 3 walls, they can be wide or narrow; and they can be shallow or deep. In general, deep and narrow defects with more bony walls have the greatest and most predictable chance for successful gain in attachment following periodontal surgery. Other factors strongly influencing the chances for attachment gains include the patient’s local, behavioral and systemic conditions and characteristics. Plaque control, smoking, systemic conditions clearly affect surgical outcomes. Treatment The goals of achieving and maintaining periodontal health lead to the endpoint of obtaining a healthy and functional dentition for life. We track progress towards that endpoint by assessing the health of the periodontal attachment apparatus structures. Therapeutic options are evaluated by the degree to which those outcomes are met, as well as with the relative costs (measured in dollars, time, morbidity, comfort, esthetics, etc.) required to achieve them. Continued All therapies which assist in limiting the deleterious effects of the host response to periodontal pathogens can be considered bone-preserving, as well as toothpreserving therapeutic options. The most effective therapies may be those most under-rated in the minds of some dental professionals. Adequate plaque control by the patient and routine scaling and root planing and adjunctive therapies in the general practice and periodontal practice are essential to attain and maintain periodontal health for most patients. Surgical therapies complement non-surgical therapies to provide a range of valuable options. The least invasive options are key! This is often accomplished through non-surgical periodontal treatment, including scaling and root planing (a careful cleaning of the root surfaces to remove plaque and tartar from deep periodontal pockets and to smooth the tooth root to remove bacterial toxins), followed by adjunctive therapy such as systemic and local delivery antimicrobials and host modulation, as needed and on a case by- case basis. Most Periodontists would agree that after scaling and root planing, many patients do not require any further active treatment, including surgical therapy. Antiseptics Antiseptics, delivered via rinsing and irrigation, have been shown to be effective in controlling gingivitis, but not periodontitis. The agents generally are not retained at the site long enough for their antimicrobial effect to provide a measurable benefit to pocket depth and/or attachment levels. Antimicrobials Delivered Locally Controlled clinical trials have consistently shown that locally-delivered sustained-release antimicrobials, along with scaling and root planing, have been shown to provide a clinically and statistically significant increase in the percentage of patients achieving predetermined periodontal benefits, than does scaling and root planing alone. Some trials have also shown that an agent alone can reduce probing depths as much as SRP alone. Continued Generally, it is agreed that these agents provide better outcomes than SRP alone in sites where patient access for plaque control might otherwise be limited; i.e. wherever pocket depths are 2 mm or greater. Improved outcomes can be obtained with these products during both active and maintenance therapy. Bacterial resistance to antibiotic therapies have not been reported, but resistance concerns can be avoided by the use the locally-delivered sustained-release antimicrobial containing chlorhexidine, an antiseptic rather than an antibiotic which is not known to induce the emergence of resistant strains Products Examples of these products which have been in the U.S. include tetracycline fibers, chlorhexidine chip, doxycycline polymer, and minocycline microspheres. A recent 3 month phase II clinical trial found that 0.4% moxifloxacin gel, a fourth-generation fluoroquinolone, administered in a single subgingival administration adjunctive to scaling and root planning, resulted in additional pocket depth reduction compared with scaling and root planing plus a placebo gel. Continued Moxifloxacin is a broad spectrum antimicrobial active against aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. These results would need to be confirmed in a phase III clinical trial. Phase II trials generally assess efficacy and dose response prior to designing a larger phase III trial. Phase III studies are generally randomized controlled multicenter trials on larger groups of patients. The goals of a phase III trial usually compares efficacy as compared to the current gold standard treatment. Another recent 9 month clinical trial indicated that microsphere formulation of doxycycline provide both a more sustained release and a high initial drug concentration as compared with doxycycline gel. All three groups (scaling and root planing alone, doxycycline microspheres and doxycycline gel) showed improvements in relative attachment levels at 9 months. The group receiving scaling and root planing plus doxycycline microspheres showed significantly greater gain in relative attachment levels than the other groups.21 Again further research is needed comparing other agents and delivery systems. Systemic Antibiotics Disrupting the biofilm mechanically is the gold standard for reducing disease. Systemic antibiotics help prevent recolonization and reorganization of the biofilm after the biofilm has been disrupted. Many studies evaluate the effect of different antibiotics in conjunction with scaling and root planing. Tetracycline Tetracycline administered as an adjunct to scaling and root planing has shown a pocket reduction greater than scaling and root planing alone. Mean pocket depth reductions were between 0.2 mm and 0.8 mm greater than scaling and root planing alone at six months (2.2 mm to 3.1 mm total reduction) in pockets 4 mm to 6 mm. Mean clinical attachment level gain at six months was 0.04 mm to 0.3 mm better than scaling alone (1.06 mm to 1.7 mm net gain). If surgical outcomes are included in the metaanalysis, then tetracycline with scaling and root planing with or without replaced flap surgery has a net attachment benefit over the intervention alone of 0.41 mm with a P = 0.003. Metronidazole Metronidazole alone has shown a mean PD change over scaling and root planing alone ranging from -.02 mm to 0.41 mm (0.46mm to 1.83 mm reduction in PD), however, these differences in pocket depth were shown not to have reached statistical significance. Clinical attachment level changes in patients taking metronidazole ranged .2 mm to 1.2 mm difference from SRP alone (0.43 mm to 2.45 mm). Metronidazole with amoxicillin after scaling and root planing in patients with chronic periodontitis mean difference in clinical attachment from scaling and root planing alone of 0.46 mm to 0.9 mm. Augmentin Augmentin with scaling and root planing have not shown to be effective in changes in PD at one year vs SRP alone. Cal levels in Augmentin ranged in difference from SRP alone by 0.16 mm to 1.3 mm (1 mm to 2.18 mm total). Clindamycin Clindamycin with SRP had CAL levels 1.6 mm better than SRP alone in sites 6 mm or greater (3 mm change) and 1.4 mm better than SRP alone overall (1.7 mm change). Changes in PD ranged from 0.2 mm to 2.3 mm between studies Azithromycin Azithromycin and SRP showed a 0.3 mm increase in PD over SRP alone at one year, whereas in sites initially 5 mm or greater, azithromycin showed 0.8 mm better than SRP alone. In sites with 6 mm or greater pocket depth, azithromycin and SRP had CAL gain over SRP alone of 0.9 mm at one year. The microbiologic makeup of the subgingival biofilm at one year after SRP and azithromycin had significantly less red complex bacteria. Within one year all other bacterial changes had reverted to near baseline. Abscesses of the Periodontium Types Periodontitis related abscess: When acute infections originate from a biofilm ( in the deepened periodontal pocket) Non-Periodontitis related abscess: When the acute infections originate from another local source. eg. Foreign body impaction, alteration in root integrity Acute The abscess develops in a short period of time and lasts for a few days or a week. An acute abscess often presents as a sudden onset of pain on biting and a deep throbbing pain in a tooth in which the patient has been tending to clench. The gingiva becomes red, swollen and tender. In the early stages, there is no fluctuation or pus discharge, but as the disease progresses, the pus and discharge from the gingival crevice become evident. Associated lymph node enlargement maybe present. Chronic This is the condition that lasts for a long time and often develops slowly. In the chronic stages, a nasty taste and spontaneous bleeding may accompany discomfort. The adjacent tooth is tender to bite on and is sometimes mobile. Pus may be present as also may be discharges from the gingival crevice or from a sinus in the mucosa overlying the affected root. Pain is usually of low intensity. Microbiology Rods Streptococcus viridans is the most common isolate in the exudate of periodontal abscesses when aerobic techniques are used. It has been reported that the microorganisms that colonize the periodontal abscesses are primarily Gram negative anaerobic rods. Although they are not found in all cases of periodontal abscesses, high frequencies of Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Campylobacter rectus, and Capnocytophagaspp have been reported. A.A? Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans is not usually detected. The disappearance of Porphyromonas gingivalis from the abscessed sites after treatment suggests a close association of this microorganism with abscess formation. Spirochetes have been found as the predominant cell type in periodontal abscesses when assessed by darkfield microscopy. Strains of Peptostreptococcus, Streptococcus milleri (S. anginosus and S. Inter medius), Bacteroides capillosus, Veillonella, B. fragilis, and Eikenella corrodens have also been isolated. Overall, studies have noted that the microbiotas found in abscesses are similar to those in deep periodontal pockets. Periodontal Abscesses 1. Porphyromonas gingivalis-55-100% 2. Prevotella intermedia- 25-100% 3. Fusobacterium nucleatum -44-65% 4. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans-25% 5. Camphylobacter rectus- 80% 6. Prevotella melaninogenica-22% What happens… After the infiltration of pathogenic bacteria to the periodontium, the bacteria and/or bacterial products initiate the inflammatory process, consequently activating the inflammatory response. Tissue destruction is caused by the inflammatory cells and their extracellular enzymes. An inflammatory infiltrate is formed, followed by the destruction of the connective tissue, the encapsulation of the bacterial mass and pus formation. The lowered tissue resistance and the virulence as well as the number of bacteria present, determine the course of infection. The entry of bacteria into the soft tissue wall initiates the formation of the periodontal abscess. How does an Abscess develop? Changes in the composition of the microflora, bacterial virulence or in host defences could also make the pocket lumen inefficient to drain the increased suppuration. Closure of the margins of the periodontal pockets may lead to the extension of the infection into the surrounding tissues, due to the pressure of the suppuration inside the closed pocket. Fibrin secretions leading to the local accumulation of pus, may favour the closure of the gingival margin to the tooth surface. Tortuous periodontal pockets are especially associated with furcation defects. These can eventually become isolated and can favour the formation of an abscess. After procedures like scaling where the calculus is dislodged and pushed into the soft tissue. Also… Periodontal abscesses can also develop in the absence of periodontitis, due to the following causes: Impaction of foreign bodies (such as a piece of dental floss, a popcorn kernel, a piece of a toothpick, fishbone, or an unknown object). Infection of lateral cysts Local factors affecting the morphology of the root may predispose to periodontal abscess formation. (The presence of cervical cemental tears has been related to rapid progression of periodontitis and the development of abscesses). Other Factors Associated with an Abscess Post non-surgical therapy periodontal abscess (Abscess may occur during the course of active non-surgical therapy) Post scaling periodontal abscess. eg. Due to the presence of a small fragment of the remaining calculus that may obstruct the pocket entrance or when a fragment of the calculus is forced into the deep, non-inflamed portion of the tissue Post surgical periodontal abscess -when the abscess occurs immediately following periodontal surgery. It is often due to the incomplete removal of the subgingival calculus Perforation of the tooth wall by an endodontic instrument. The presence of a foreign body in the periodontal tissue (eg. Suture / pack) Post antibiotic periodontal abscess -treatment with systemic antibiotics without subgingival debridement in patients with advanced perio may cause abscess formation. Diagnosis Diagnosis depends on many factors – and whether pain is present will differentiate from an acute or chronic abscess. Asking if the client smokes is very important – as this could delay healing time for the periodontal abscess or gum disease in general. Everything needs to be examined included the lesion, oral hygiene, clients medical and dental history, mobility, pus, swelling, redness, etc. How to Confirm Radiographs – There are several dental radiographical techniques which are available (periapicals, bitewings and OPG) that may reveal either a normal appearance of the interdental bone or evident bone loss, ranging from just a widening of the periodontal ligament space to pronounced bone loss involving most of the affected cases. Intra oral radiographs, like periapical and vertical bite-wing views, are used to assess marginal bone loss and the perapical condition of the tooth which is involved. A gutta percha point which is placed through the sinus might locate the source of the abscess. Vitality Test The Pulp Vitality Test – The Pulp vitality test, like thermal or electrical tests, could be used to assess the vitality of the tooth and the subsequent ruling out of the concomitant pulpal infections. Microbial and Lab Testing Microbial Test - Samples of pus from the sinus/ abscess or that which is expressed from the gingival sulcus could be sent for culture and for sensitivity tests. Microbial tests can also help in implementing the specific antibiotic courses. Lab Testing Lab tests may also be used to confirm the diagnosis. The elevated numbers of the blood leukocytes and an increase in the blood neutrophils and monocytes may be suggestive of an inflammatory response of the body to bacterial toxins in the periodontal abscess. Other Others Multiple periodontal abscesses are usually associated with increased blood sugar and with an altered immune response in diabetic patients. Therefore, the assessment of the diabetic status through the testing of random blood glucose, fasting blood glucose or glycosylated haemoglobin levels is mandatory to rule out the aetiology of the periodontal abscess. Types Gingival Abscess Features that differentiate the gingival abscess from the periodontal abscess are: i. History of recent trauma; ii. Localisation to the gingiva; iii. No periodontal pocketing Periapical Abscess Periapical abscess can be differentiated by the following features: i. Located over the root apex ii. Non-vital tooth, heavily restored or large filling iii. Large caries with pulpal involvement. iv. History of sensitivity to hot and cold food v. No signs / symptoms of periodontal diseases. vi. Periapical radiolucency on intraoral radiographs. Perio-Endo PERIO-ENDO LESION i. Severe periodontal disease which may involve the furcation ii. Severe bone loss close to the apex, causing pulpal infection iii. Non-vital tooth which is sound or minimally restored ENDO-PERIO LESION Endo-perio lesion can be differentiated by: i. Pulp infection spreading via the lateral canals into the periodontal pockets. ii. Tooth usually non-vital, with periapical radiolucency iii. Localised deep pocketing Cracked Tooth Syndrome Cracked tooth Syndrome can be differentiated by: i. History of pain on mastication ii. Crack line noted on the crown. iii. Vital tooth iv. Pain upon release after biting on cotton roll, rubber disc or tooth sleuth v. No relief of pain after endodontic treatment Root Fracture Root fracture can be differentiated by the presence of: i. Heavily restored crown ii. Non-vital tooth with mobility iii. Post crown with threaded post iv. Possible fracture line and halo radiolucency around the root which are visible in periapical radiographs v. Localised deep pocketing, normally one site only vi. Might need an open flap exploration to confirm diagnosis Treatment 1. Local measures i. Drainage ii. Maintain drainage iii. Eliminate cause 2. Systemic measures in conjunction with the local measures The management of a patient with periodontal abscess can divided into three stages: i. Immediate management ii. Initial management iii. Definitive therapy Antibiotics Antibiotics are prescribed empirically before the microbiological analysis and before the antibiotic sensitivity tests of the pus and tissue specimens. The empirical regimens are dependent on the severity of the infection. The common antibiotics which are used are: 1. Phenoxymethylepenicillin 250 -500 mg qid 5/7 days 2. Amoxycillin 250 - 500 mg tds 5-7 days 3. Metronidazole 200 - 400 mg tds 5-7 days If allergic to penicillin, these antibiotics are used: 1. Erythromycin 250 –500 mg qid 5-7 days 2. Doxycyline 100 mg bd 7-14 days 3. Clindamycin 150-300 mg qid 5-7 days Initial Therapy - Acute a. The irrigation of the abscessed pocket with saline or antiseptics b. When present, the removal of foreign bodies c. Drainage through the sulcus with a probe or light scaling of the tooth surface d. Compression and debridement of the soft tissue wall e. Oral hygiene instructions f. Review after 24-48 hours; a week later, the definitive treatment should be carried out. Periodontal The treatment options for periodontal abscess under initial therapy: 1. Drainage through pocket retraction or incision 2. Scaling and root planning 3. Periodontal surgery 4. Systemic antibiotics 5. Tooth removal Conclusion The occurrence of periodontal abscesses in patients who are under supportive periodontal treatment has been frequently described. Early diagnosis and appropriate intervention are extremely important for the management of the periodontal abscess, since this condition can lead to the loss of the involved tooth. A single case of a tooth diagnosed with periodontal abscess that responds favourably to adequate treatment does not seem to affect its longevity. In addition, the decision to extract a tooth with this condition should be taken, while taking into consideration, other factors such as the degree of clinical attachment loss, the presence of tooth mobility, the degree of furcation involvement, and the patient’s susceptibility to periodontitis due to the associated systemic conditions.