Jody Camarra – Literature Review DRAFT 4/24/12

advertisement

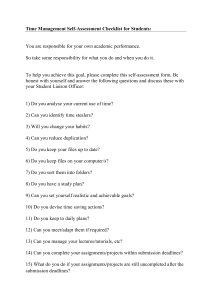

Jody Camarra – Literature Review DRAFT 4/24/12 ED602; Spring 2012 Literature Review This literature review explores research about reflective learning, critique and selfassessment in the art classroom. Research supports the idea that connecting the three can lead to a higher level of comprehension and retention and the development of critical thinking skills in students. The following review considers the perspectives of psychologists and art educators who discuss reflective learning and critique in the art classroom. Reflective Learning and Dialogue in the Classroom You should reverse the order of this section. The more theoretical research should come first and then the practice-based research. Research done in this field over the past few decades argues that reflection strengthens a student’s ability to organize new knowledge with greater meaning and success. The project for school innovation is an initiative of the Neighborhood House Charter School, a tuition-free public school serving K-8 students in Dorchester, Massachusetts. In their book, is it a book or an article? Cultivating Student Reflection: The Cambridgeport School (2003), you need the first name and the names of all the authors when you first mention them. Charner-Laird et al., attest that in a world over-saturated with information and ever-increasing speed, reflection helps us to slow down and recognize the depth and breadth of learning. They discuss the challenge of teaching reflectively, of seeking a sense of purpose, connectedness and understanding, as well as the positive impact of reflective learning. They identified that students in reflective learning environments are self-aware and self-critical and can evaluate their own learning strengths, challenges and strategies, choosing activities based on what they need or want to work on. Charner-Laird et al., indicate that these learners can articulate what they want to learn and why, using information about their own thinking and learning to make decisions and self-assess. The authors state that these students see themselves, their peers, and adults, as learners. Martha Taunton, an art educator, calls for reflective dialogue as an effective teaching strategy for cultivating reflective learning. In her article, “Reflective Dialogue in the Art Classroom: Focusing on the Art Process” (1984), Taunton argues that reflective dialogue should serve as more than an account of classroom activities or steps in a lesson. It can serve as a way to check for understanding of the aim of a lesson, or of what occurred in the art-making process. Listening to children talking about their art-making can give value to what they contemplate as they make art. Taunton theorizes that through the process of communication, children’s understanding of their efforts in art-making grows. She argues that the relationships between what children do as artists and what other artists do can be connected in children’s minds. “Questions and comments posed by the teacher at different stages of art-making, tend to focus and clarify children’s thinking about their ideas and intentions, procedures they are following, and solutions they devise. Teachers’ questioning strategies can be designed to develop knowledge of one’s actions as an artist and to establish a more general awareness of art-making” (Taunton, p.15). In 2003 Mary Jane Zander, an art educator, published a review of literature related to talk in the art classroom and a discussion of how trends in the study of discourse may have important implications for research in art education. In art education there are many studies that investigate classroom conversations or interactions and analyze the kinds of student/teacher talk found in classrooms. The most common finding is that classroom talk is generally teacher-dominated. However, there is significant literature available in other disciplines indicating that learning is related to the development of a "discourse community" and that learning to understand a discipline requires learning to talk and think in the discourse of that community. Zander discusses the classroom as a community in which students create meaning by participating in a variety of discourses. Zander observed that in many cases teachers encouraged creativity by creating opportunities for multiple forms of discourse and constructing a safe place in which to share ideas. This often involved knowing when to refrain from offering or imposing opinions in order to encourage student exploration. Often, refraining from teacher talk empowered students to think and speak for themselves. Like Taunton, Zander (2004) argues that an environment in which reflective dialogue is encouraged benefits the learner. Driven by assessment, learning benchmarks, and the requirement to teach a certain amount of information within a specific time period, the standard curriculum leaves little room for creating dialogical relationships. Taunton asserts that the challenge becomes how to create an environment in the art classroom that is friendly to student opinion and welcomes self-expression while maintaining educational purpose. She notes that often teachers don't know how to design learning activities that are open-ended or a classroom culture that is open to student opinion, leading to a lack of structure in the art classroom. It is Zander’s observation that teachers are often afraid that if they encourage discussion, students will get out of control or will use this as an opportunity to ramble meaninglessly. In her article, “Art Dialogue in the Classroom ” (2007), Connie Stewart, an art historian and art educator , cites studies showing that two-thirds of the talk in a typical classroom is done by the teacher (Zander, 2004). She contends that classroom questioning often follows a pattern of teacher-initiated question, student response, followed by another teacher-initiated question. She maintains that a successful art dialogue depends on creating a safe environment that encourages the expression of opinion and ideas. An art dialogue can be encouraged with the assumption that some questions will not have a right answer, and that a wrong interpretation is still an interpretation and we all can learn from another’s viewpoint. Stewart claims that the teacher should ask provocative questions, provide affirmation for respondents when needed, and direct the questions back to the group. In his article, “Dialogue With Form” (2007), Ted Zourntos, a painter and art educator, examines the communicative characteristics of images by combining studio drawing with directed group critique. The author notes that the more comfortable students became with the ideas discussed in class, the more inclined they were to take the dialogue further and interpret the images more thoroughly, forming personal and critical opinions. Critique Much has been written about different critique strategies and their effectiveness in creating a reflective learning environment and thereby encouraging critical thinking in school aged children. Terry Barrett, an art educator, discusses the importance of introducing more interpretation and less evaluation and judgment during student critiques. He also argues for the positioning of viewers as central to the critique and offer strategies for changing a negative critique into a positive and constructive discussion. He supports de-emphasizing the opinion of the teacher to place primary responsibility on the students to evaluate art. In this way they can continue to look at art that they and others make and intelligently consider it, independently of the artists and of teachers. In her journal article, “Using Critiques in the K-12 Classroom” (2008), Nancy House, an art educator????, focuses on critiques as a useful component in the art classroom. House argues that critique can be a useful teaching tool for any age group studying the visual arts. House suggests that in the K-12 classroom, the critique should include both positive reinforcement and constructive criticism. She discusses critique that occurs in process, while students are actively engaged in developing ideas and making art. Like Charner-Laird et al (2003), House argues that critique in process provides students time to slow down, step back and reevaluate their next steps. House contends that this slowing down helps students move beyond the ‘I like it that way’ statement as they are encouraged to reflect upon their own and the work of others. In doing so, they articulate what they see, developing the necessary vocabulary to express their thoughts. Barrett (2000) asserts that students' best experiences with critiques occurred when instructors demonstrated that they care for the individual student, foster a spirit of goodwill, protect students from humiliation, and leave students inspired to do more and better work. He concluded that teachers must maintain a learning environment that is physically and emotionally safe regardless of the grade or age they teach in order to cultivate a reflective learning environment and conduct effective critiques. Self-Assessment This section discusses the literature about self-assessment, a process during which students collect information about their own performance or progress, compare it to explicitly stated criteria, goals, or standards, and revise accordingly. Some of the research is about general elementary education and not specific to the art classroom, but it is relevant to the art classroom as well. In accord with Taunton, Leslie Cunliffe, an art educator, also weighs in on the ideal learning environment. In his article, “Towards a More Complex Description of the Role of Assessment as Practice for Nurturing Strategic Intelligence in Art Education” (2007), Cunliffe raises questions about the purposes and practices of assessment in the classroom, strongly favoring those that promote and cultivate self-regulated learning and creativity. Cunliffe maintains that cognitive resources like language, knowledge and skills only serve to answer the “know how” or “know what” questions. He asserts that an ideal learning environment must also facilitate the “know why” question. He writes that the “know why” question is “a meta-cognitive resource” which helps the student know how best to deploy the content learned from the “know what” and “know how” questions. Cunliffe’s point of view is that it would be useless to have a fine set of tools without knowing how to use them properly, or to have to rely on others to give directions each time someone wanted to use them correctly. Lois Hetland, an art educator and researcher at Project Zero, conducts research in cognitive and developmental psychology focused on issues of learning, teaching, and disciplinary understanding, with an emphasis on the arts. She was a member of a research development project that developed the Studio Thinking Framework (date) by studying artist-teachers at two Boston area high schools that take the arts seriously. Phase 2 of the project focused on describing student learning, and Phase 3 works with generalist and arts teachers in Alameda County, California, to understand how teachers learn and use the framework in planning, teaching, and assessment. A teachers' handbook is in preparation. In their book, Studio Thinking, Hetland you need the names of all the authors the first time you mention the book. document a two-step process in student reflection. The authors argue that students must understand the specifics of their own work process in order to evaluate the effectiveness of their art. Learning to reflect is one of the habits cultivated in strong visual arts classrooms. In the first step of the reflection process, which Hetland et al., describe as question and explain, students describe their art-making process. In the second step, which Hetland et al., label as evaluate, students judge their own work and others. The first step is necessary in this reflection process because students must understand the specifics of their own work process in order to evaluate the effectiveness of their art. You repeated this sentence word for word—see above. You should revise. Project Zero makes it their primary mission to investigate the development of learning processes and to understand and enhance learning, thinking and creativity in the classroom (Project Zero, date). Is this a direct quote?. Combining theory with practice, Project Zero’s research intends to combine basic inquiry with contemporary work in schools, with their goal being to create communities of reflective learners, to enhance deep understanding within the disciplines and to promote critical creative thinking. (Giudici, Rinaldi & Krechevsky, 2001) Project Zero researchers’ place human cognitive development at the center of the learning process, respecting the way the individual learns at various stages, as well as their perceptions and expressions of ideas. In collaboration with Reggio Emilia and teachers in various Massachusetts K-12 classrooms, Project Zero researchers investigated the role of documentation as a means to create visible evidence of collaborative learning in a constructivist-inspired classroom. In the book, Making Learning Visible: Children as Individual and Group Learners (2001), Project Zero researchers explore the subject of assessment and evaluation. They note that in the American context, assessment and evaluation are usually synonymous with a process of judgment, measuring, or comparison of work. Throughout the 20th century, assessment in American schools has been dominated by tests, quizzes or short essays intended to evaluate what a student has comprehended and whether or not students have retained the content of a lesson. Tests are often time-based and comprised of short answers, multiple choice, and quick response answers regarding de-contextualized “factual” questions. According to the researchers, tests offer very few options for learners to represent creative thought. The Project Zero researchers assert that by using visual documentation of collaborative classroom projects, evidence can be seen of what and how children are learning. Self-Assessment and Self-Regulated Learning Gary Bingham, along with Teri Holbrook and Laura Meyers, researched the use of self-assessment in elementary art???? classrooms . In their article, “Using Self-Assessment in the Elementary Classroom” (2010), the authors discuss the benefits of self-assessment for student artists. Binghman et al., argue that self-assessment encourages students to understand their own learning. The authors attest that self-assessment can also increase student motivation and ownership over their own learning. Bingham et al., assert that even the youngest students can self-assess meaningfully as long as it is taught in developmentally appropriate ways. Bingham et al., report that self-assessments can play a powerful role in developing a child's motivation and achievement by requiring students to think carefully about what they have learned and how they learn and to develop criticalthinking and problem-solving skills. Bingham et al., conclude that students who engage in the productive practice of self-assessment inevitably strengthen their own learning and development. Heidi Goodrich Andrade and Anna Valtcheva, art educators as well as researchers for Project Zero, explore formative assessment and the crucial role of feedback in learning in their article, “Promoting Learning and Achievement through Self-Assessment (2009). Andrade and Valtcheva point out that research has shown that feedback promotes learning and achievement, yet many students get little informative feedback on their work. They attribute the scarcity of feedback in many classrooms to the fact that few teachers have the luxury of regularly responding to each student's work. Andrade and Valtcheva cite research showing that students themselves can be useful sources of feedback through selfassessment. Like Barrett (1997), Andrade and Valtcheva conclude that self-assessment is a key element in formative assessment because it involves students in thinking about the quality of their own work, rather than relying on their teacher as the sole source of judgments and evaluation. The authors discuss self-assessment as a useful tool in delineating progress toward goals. Criteria-referenced self-assessment is a process during which students collect information about their own performance or progress, compare it to explicitly stated criteria or standards, and revise accordingly. Andrade and Valtcheva(2009) argue that self-assessment must be a formative type of assessment, done on drafts of works in progress. They contest it should not be a matter of determining one's own grade, but rather to identify areas of strength and weakness in one's work in order to make improvements and promote learning. Research has shown criteria-referenced self-assessment to promote achievement. Andrade was also the principal investigator on Project Zero’s Rubrics and SelfAssessment Project supported by the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation in the late 1990s. The two studies that made up Project Zero's research focused on the effect of instructional rubrics and rubric-referenced self-assessment on the development of 7th and 8th grade students' writing skills and their understandings of the qualities of good writing. The second study looked at the effects of instructional rubrics and guided self-assessment on students' writing and understandings of good writing. The results of Study 2 suggest that rubric-referenced self-assessment can have a positive effect on girls' writing but no effect on boys' writing. In broad strokes, this is consistent with research cited by Andradeon sex differences in how boys and girls respond to feedback. Andrade( are you still talking about Adnrade? It is not clear) mention in their findings that study 2 did not examine students' cognitive and emotional responses to self-assessment, however, so this explanation of the differences between boys and girls is speculative. The different ways in which boys and girls respond to self-assessment need to be better understood. The literature on self-regulated learning and feedback seems to agree that the most effective learners are self-regulating. Self regulation is a style of engaging with tasks in which students exercise a suite of skills including setting goals for upgrading knowledge, deliberating about strategies to select those that balance progress toward goals against unwanted costs, and as the task evolves, monitoring the effects of their engagement. Self-regulated learning reinforced in the research of Deborah Butler and Philip Winne, (1995), who suggest that learning improves when feedback reminds students of the need to monitor their learning and guides them in how to achieve learning objectives. Winne, a psychologist and Canada Research Chair, in self-regulated learning and learning technologies, and Butler, a psychologist, conclude that this awareness provides ground on which the students judge how well unfolding cognitive engagement matches the standards they set for successful learning. Researchers from Arts Propel, an arts assessment project at Harvard, identified the ability to articulate artistic goals as a component of student reflection. (names? Dates?) Self-assessment helps students self-regulate and evaluate where they are in relation to the goals they have set for themselves. You need to elaborate here if you are going to introduce this new source. Who is arguing this? Is this also about self- assessment and self-regulated learning? If so, you need to say that this is another Reflective assessment grows out of strong theoretical roots including ancient Greek thought, the philosophy of John Dewey, and cognitive constructivist learning theories. Reflective assessment is a formative process through which students can experience assessment as a part of learning, rather than as a separate evaluative process. Over the last two decades alternative assessment strategies have become an important part of the debate regarding the reform and restructuring of American education. The purpose of assessment should be to improve student learning, which means it should be integral to the teaching and learning process. For this to occur, a seamlessness needs to exist between teaching, learning, and assessment through which students are empowered to take increased responsibility for their learning. Bibliography I changed most of your citations to reflect the APA guidelines. Please look at these changes VERY carefully because you will need to use the APA style from now on. YOu should then complete the rest. Andrade, H., (199 ??). Rubrics and self-Assessment,. Project Zero, Harvard Graduate School of Education. You need the URL and the date accessed. Andrade, H., Valtcheva, A., (2009). Promoting learning and achievement through selfAssessment. Theory into Practice, 48 (1) YOU NEED TO INSERT THE PAGE NUMBERS OF THE . Barrett, T., (1997) Talking about student art. Worcester, Mass: Davis Publishing. Barrett, T. (2000) Studio critiques of student art: As they are, as they could be with mentoring. Theory into Practice 39 (1) PAGE NUMBERS OF THE ARTICLE Bingham, G., Holbrook, T., and Meyers, L., (2010). Using Self-Assessment in Elementary Classrooms. Phi Delta Kappen, 91 (5) PAGE NUMBERS OF ARTICLE Butler, D. & Winne, P. (1995). Feedback and self-regulated learning: A theoretical synthesis. Review of Educational Research, 65(3), 245-281. Charner-Laird, K., Fiarman, S., Won Park, F., Soderberg, S. (2003). Cultivating Student Reflection: The Cambridgeport School , Project for School Innovation. IS THIS FROM A JOURNAL ? INCLUDE THE NAME ANDVOLUME ETC. IF NOT, YOU NEED THE URL AND THE DATE ACCESSED . Cunliffe, L..(2007). Using Sssessment in knowledge-rich rorms of learning and creativity to nurture self-regulated strategic intelligence. I T. Rayment (ed.) The problem of assessment in art and design (pp. 89-106). Bristol: Intellect Books. Giudici, C., Rinaldi,C. & Krechevsky, M. (Eds.). (2001) Making learning visible: Children as individual and group learners. Reggio Emilia, Italy: Reggio Children. Goodrich, H. (1996a). Student self-assessment: At the intersection of metacognition and authentic assessment. Doctoral dissertation. Harvard University. Cambridge, MA. Goodrich, H. (1997b). Thinking-centered assessment. In S. Veenema, L. Hetland, & K. Chalfen (Eds.), The Project Zero classroom: New approaches to thinking and understanding. Cambridge, MA: Project Zero, Harvard Graduate School of Education. You need to put the URL and the date accessed Hetland, L., Studio Thinking…you need to fix this House, N., (2008). Using Critiques in the K-12 Classroom. Art Education; May2008, Vol. 61 Issue 3, p48. Stewart, C. (2007). Art Dialogue in the Classroom , Collage, University of Northern Colorado. Taunton, M. (1984). Reflective Dialogue in the Art Classroom: Focusing on the Art Process, Art Education, Vol. 37, No. 1, National Art Education Association. Zander, M.J. (2003).Studies in Art Education, Vol. 44, No. 2 (Winter, 2003), pp. 117-134 Zander, M.J. (2004). Becoming Dialogical: Creating a Place for Dialogue in Art Education, Art Education Vol. 57, No. 3, May 2004. P. 51 Zourntos, T. (2007). Dialogue With Form, Art Education; November 2007, Vol. xx Issue x, p101-18.