Corporate and Project Financial Analysis - edbodmer

advertisement

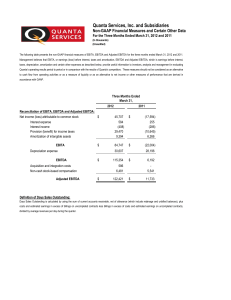

Corporate and Project Financial Analysis Programme Background on Forecasting, Ratios and Drivers of Value Every Subject in Finance Boils Down to Two Subjects Every decision in finance is in one way or another derived from how much the outcome of the decision is worth. Valuation is the single financial analytical skill that managers must master. • Valuation analysis of debt or equity involves assessing 1. Future cash flow levels, (cash flow is reality) and 2. Risks in valuing those cash flows, whether it be the cash flow from assets, debt or equity • Measurement value – forecasting and risk assessment -- is a very complex and difficult problem. • Coming up with a measurement of risk is extremely difficult and things like beta, value at risk and credit scoring have not worked very well. 2 Project Finance versus Corporate Finance Corporate Finance Project Finance • Analysis is founded on history and • Since there is no history a series of evaluation of how companies will consulting and engineering studies evolve relative to the past. must be evaluated. • Financing is important but • The bank assesses whether the necessarily the primary part of the project works (engineering report). evaluation. • Focus on cash flow. Equity IRR and • Focus on earnings, P/E ratios, DSCR EV/EBITDA ratios and Debt/EBITDA 3 History and Forecasts in Corporate Analysis • History in Corporate Forecasts – Project Finance versus Corporate Finance – Example of Financial Ratio • Interest Coverage Ratio • Debt Service Coverage Ratio – Formula to Interpret Financial Ratio • Percent Reduction in Cash Flow = (ICR-1)/ICR or (DSCR-1)/DSCR • Cash Flow = 150, Interest is 75: Percent Reduction is 50% • Compute Interest Coverage Ratio for Case • Problem with History – Not available in project finance – Sudden changes from historic numbers 4 Industry versus Firm and Management Analysis to Evaluate Potential Cash Flow Variation • Industry Analysis – – – – – Drivers of price and demand volatility Cost Structure of industry, fixed and variable cost Long-run and short-run marginal cost Capitals expenditures required to sustain EBITDA Product life cycle • Company/Competitive Advantage Analysis – – – – Competitive position Drivers of market share Customer tastes Relative cost structure Exercise: Use INDEX function to see the defaults by year and by industry • S&P - Industry Risk, Country Risk and Competitive Position 5 Industry Risk: Cyclicality • Companies where earnings show cycles of major rises and declines Examples: Retail, property, paper, cars, chemicals, • Characteristics: – – – – airlines, steel, primary metals, houseCyclical downturn in recession building, building materials, advertising, Producers over-invest at peak capital goods, shipping. Supply rises Prices fall sharply when demand declines because of surplus capacity • Cash available for investment at peak • Rational behavior to not invest is limited by desire to maintain market share • Example: Rates to move a 20 foot container from Hong Kong to Northern Europe have fallen from about $12,0000 to roughly $220, creating the deepest ever crisis in the industry. (FT 08). 6 Exercise on Cyclical Industry: Rates for Shipping • • • • Go to St. Louis FRED data Find the relevant URL’s Copy the data to Excel Sheet Create Macro to Download the Data Key is to use the WORKBOOKS.OPEN statement in a macro together with the INDEX Function 7 Country Risk, Macro-economic Factors and Cyclicality Macro Economic Policy Result Excessive Liquidity and Low Interest Rates Leads to Overlending U.S. Subprime Crisis, Spain Construction Higher Interest Rates to Slow Down the Economy U.S. Commercial Real Estate in 1980’s Unemployment Increase Slows Down Demand U.S. Recession of 2008 and Bankruptcy of GM Suppliers 8 Economics of Price Volatility in Industry Analysis • Demand Volatility – Technical Definition of Volatility – Different Distributions – Income Elasticity Exercise: Compute volatility from data that is downloaded from the industry analysis sheet • Capital Expenditure Changes • Difference between Long-Run Marginal Cost and Short-Run Marginal Cost – Driven by Capital Intensity and Operating Leverage • Capital Intensity of Assets – Lifetime of Assets – Revenues versus Operating Costs • Operating Leverage 9 Operating Leverage • Definition: Fixed Expenses that do not vary with sales • Definition of Fixed and Variable Costs – – – – – Not in Financial Statements COGS generally includes depreciation which is fixed Administrative expenses are related to sales when many are fixed Semi-fixed expenses that change after passage of time Pension obligations and costs of employee reductions Exercise: Analysis of Fixed and Variable Expenses Open a Financial Statement File Use F11 to make graph of revenues and operating expenses Remove title and create scatter plot 10 Investment to Maintain Cash Flow and Profits • To generate profits or cash flow, just about everything requires some level of investment: – – – – – – – Personal: Invest in education High Tech: Invest in research and investment Start-up: Invest in marketing and service or product Telecom: Invest in acquisitions and licenses Retailing or Trading: Invest in Inventories Banking: Invest in Loans Manufacturing: Invest in Capital Expenditures • If a company stops investing or makes bad investment decisions, or pays too much for investments, it will have problems in the future 11 Example of Industry Analysis – Peak to Trough Percent (PTT) 12 Industry Default History 13 Moody’s Default Rates by Industry 14 Corporate and Project Financial Analysis Programme Qualitative Discussion of Risk Qualitative Checklists • • • • • Economic and Demand Volatility Risks Cost Input Risks Obsolesce Risks Regulatory Changes Political Risks 16 Standard and Poor’s Check List for Business Risk Key Industry Characteristics And Drivers Of Credit Risk Credit risk impact: High (H); Medium (M); Low (L) Risk factor Industry Airlines (U.S.) Autos* Auto suppliers* High technology* Mining* Chemicals (bulk)* Hotels* Shipping* Competitive power* Telecoms (Europe) Cyclicality H H H H H H H H H H M Competition H H H H H H H H H H H Does this help very much Capital intensity Technology risk H L H M H M M H H M H L H L H L H L M L H H Regulatory/Gov ernment M/H M M L M/H M M L L H H Energy sensitivity H H M L/M H L H M M H L Exercise: Use Lookup function to rank industries 17 Company and Industry Economic Factors – Really Measuring the Demand Volatility • • • • • • • • • Home economy situation and trends Overseas economies and trends Seasonality/Weather Issues Market and trade cycles Specific industry factors Market routes and distribution trends Customer/end-user drivers Interest and exchange rates International trade/monetary issues Combine these Factor with: • Barriers to entry • Capital Intensity • Operating Leverage • Construction Lag Declining Demand Difficult to Downsize Rise in Input Costs Inefficient vs. Competitors Technical Problems Reputational Damage Working Capital Control Customer Concentration 18 Demand Volatility Driven by Changes in Attitudes • • • • • • • • • • • Lifestyle trends Demographics Consumer Attitudes Media Views Brand, Company, Technology Change Consumer Buying Patterns Fashion and Role Models Major Events Buying Access and Trends Advertising and Publicity Ethical Issue 19 Examples of Risks – Economic Risks and Barriers to Entry • Definition: Prices fall because of surplus capacity; demand falls because of economic volatility; competition increases; • First Solar Case: Danger of Falling From Power House to Capital Junkie • Other cases: Solar companies, telecom companies, subprime crisis 20 Obsolescence, Technological Change and Regulatory Changes • Technical Obsolescence – Polaroid, Kodak, Maps, Guidebooks, CD players, DVD players • Impact of Internet – Retail, Newspapers, Music, Travel Agents • Impact of EMG Competition – Textiles, general manufacturing 21 Technology Risk • Definition: Demand falls because of available new technology; capital expenditures and/or costs for new technology changes Projected and Actual Revenues for Iridium • Iridium Case 9,000,000 Actual Salomon Smith Barney 8,000,000 Credit Suisse/First Boston 7,000,000 Lehman Brothers 6,000,000 Merrill Lynch CIBC Oppenheimer 5,000,000 4,000,000 3,000,000 2,000,000 1,000,000 0 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 • Other cases: HP, RIM, Nokia, Kodak 22 Checklists – Political Risks • • • • • • • • • Ecological/environmental issues Current and future legislation Regulatory bodies and processes Government term and change Funding, and grants International pressure groups Austerity measures Capital controls, wars and conflict More licenses awarded, withdrawal of government support, sharp price reductions mandated 23 Environmental Risks • GDF Coal Plant in Italy • Italian police have seized control of a coal-fired power plant in Savona, shutting it down after a judge ruled in favor of arguments that the plant was responsible for 442 premature deaths between 2000 and 2007, and a further 2,000 cases of heart and lung disease. The owner of the plant, Tirreno Power, which is controlled by France’s GDF Suez, was deemed to have exhibited “negligent behavior” by the judge, who also said the emissions data from the plant was “unreliable”. Emissions from coal-fired plants pose well-known health risks, and GDF Suez is already under fire for its involvement in a major coal disaster in Australia, where an open cast coal mine caught fire and burned for over a month, leading to evacuations and severe health impacts on residents. The coal plant closure in Italy and mine fire in Australia have exacerbated a bad start to the year for GDF Suez, which has written down €14.9 billion in fossil assets on its books due to strong competition from renewables. 24 Political/Legal Risks • Definition: Will companies continue to honor uneconomic contracts • Example: Dabhol Plant in India • Other Examples 25 Risks and Causes of Project Failure • • • • • • • • • • • • • Delay in completion (increase in IDC) Capital cost over-run Technical Failure Revenue Contract Default Increased Price of Raw Materials Loss of Competitive Position Commodity Price Risk Volume Risk Overoptimistic Reserve Projections Exchange rate Technical Obsolescence of Plant Financial Failure of Contractor Uninsured Casualty Losses • • • • • • • • • • • • US Nuclear Plants Eurotunnel / Samsung Heavy Industries Alstrom Combined Cycle Dabhol; AES Drax Austrian/California Wood Plants Natural gas plants Argentina Merchants Pocantas Toll way; Subways Philippines Project PT Pation in Indonesia Iridium Hima Power Plant in India 26 Largest Defaults by Year 27 Selected Defaults including Lehman Brothers in 2008 28 Corporate and Project Financial Analysis Programme Assessing Commercial Risks and Mitigation Risk Matrix and Credit Memorandum • Measuring Risks is Probability Impossible • Discussion of Risks – Classify Risks – Define Risks – Mitigation of Risks – Probability and Magnitude – Buffer to Accept Risks 30 Managerial Risk • Growth Strategy and True Competitive Advantage (First Solar) • Power House Square to Capital Destruction Square (Kalitta) • Pricing Strategies and Risks (Iridium) • Enron, VW, Constellation (Hiding Information) • Re-financing in Corporate Finance after lack of confidence in management 31 Cost Structure • Understand Fixed and Variable Costs (UAL, GM) • Required Maintenance Capital Expenditures (Airlines, Nuclear Plants) • Use of Historic Trends and Danger of Multi-year Economic Expansion (1990’s, 2002-2006) • Problem: How can you really assess fixed and variable costs in financial reports • Exercise: Scatter Plot – Use F11 and eliminate the name of the X-axis 32 Short-term Risks • Inventory Risk (Launer) – Trading company buys gifts for sale to large retail stores. Tastes and demand changes. Left with inventory that has a lot less value. • Receivables Risk – Sales made to customers who do not make payments because of bankruptcy. • Trade receivables age analysis – Evaluate the accounts receivable as percent of sales • Supplier Risk • Example: Loss of $55 million related to the bankruptcy of one of our domestic coal suppliers. During the first quarter of 2008, as a result of a default by the supplier, we terminated our derivative contracts with the supplier, reclassified the related asset to accounts receivable, and fully reserved the amount. • Danger of exposure to single customer; Inventory holding risk 33 Corporate and Project Financial Analysis Programme Evaluating Cash Flow and Source of Repayment Primary Source of Repayment for Credit Analysis • Project finance source of repayment is cash flow – Cash flow after taxes and maintenance capital expenditures – Examples • Corporate finance – When a company grows, it would be bad to repay all debt – Source of repayment is strong enough financial ratios to refinance – When markets loose confidence, companies go bankrupt • Examples: Enron, Constellation Energy, Lehman Brothers • How can you assess when re-financing becomes not possible 35 Cash Flow and Debt Repayment • Primary source of repayment for: – Project Finance – Leverage Acquisitions • Secondary source of repayment for: – Corporate finance when stop discretionary capital expenditures – Related to financial ratios in corporate finance 36 EBITDA – General Discussion • Definition as revenues related to basic operations coming in versus cash expenses going out • Computation of EBITDA and Measurement Issues • Understanding and Dissecting Trends in EBITDA • Acquiring Long-term data on EBITDA (read PDF) • Adjusting EBITDA for Exploration Expenses, Rental Expenses and Other Factors 37 Income Statement • Review trends in EBITDA, EBIT, EBT and Net Income and explain what is happening to the company • EBITDA includes operating earnings and other income, but it does not include foreign exchange gains or losses, minority interest, extraordinary income or interest income. – EBITDA is a rough proxy for free cash flow – EBITDA is not generally shown on Income Statement – Potential Adjustments for items such as exploration expense – Compare EBIT to Net Assets and Net Capital • Ratio of EBITDA to Revenues (EBITDA margin) should be shown for historic and projected periods • EBITDA is related to un-levered cash flow while Net Income and EPS are after leverage • NOPLAT is computed by EBIT less adjusted taxes, where taxes are computed through adjusting income taxes. 38 Standard Computation of EBITDA 39 Exercise: Compute EBITDA • Samsung and Chesapeake Energy – Download PDF – Use Read PDF file – Use Arrange Titles with Union Function – Use Match and Index to Arrange Data – Compute EBITDA 40 EBITDA and Project Life • If Project Life is 2 years, ROIC is 10% and Investment is 1000. – EBIT = EBITDA – 500 – EBIT = 1000 * 10% = 100 – EBITDA = 600 • If Project Life is 2 years, ROIC is 10% and Investment is 1000. – EBITDA = EBITDA – 50 – EBIT = 1000 * 10% = 100 – EBITDA = 150 • Debt to EBITDA and EV to EBITDA should be Different 41 Income Statement Analysis and Adjustments to EBITDA • Example of Adjustments to EBITDA – Exploration Expenses (EBITDAX) – Rental and Lease Payments (EBITDR) • EBITDA Computation – Top Down – move other income – Bottom-up (Indirect) • EBITDA Notes – Interest Income out of EBITDA – Interest Expense not in EBITDA – Understand Non-cash Expenses • Deferred Mining Costs • Equity Income • Minority Interest 42 Problems with EBITDA • EBITDA is useful in its simplicity, and can be a good reference for comparison of debt and value, but it has weaknesses: – EBIT is more important than DA, because must use cash for replacing depreciation and amortization – In credit analysis, EBITDA works better for low rated credits than high rated credits. (Moody’s) – EBITDA is a better measure for companies with long-lived assets – EBITDA can be manipulated through accounting policies (operating expenses versus capital expenditures) – EBITDA ignores changes in working capital, does not consider required re-investment, says nothing about the quality of earnings, and it ignores unique attributes of industries. 43 S&P Definition of EBITA • • • Our definition of EBITDA is: Revenue minus operating expenses plus depreciation and amortization (including noncurrent asset impairment and impairment reversals). We include cash dividends received from investments accounted for under the equity method, and exclude the company's share of these investees' profits. This definition generally adheres to what EBITDA stands for: earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization. However, it also excludes certain other income statement activity that we view as nonoperating. Our definition of EBITDA aims to capture the results of a company's core operating activities before interest, taxes, and the impact on earnings of capital spending and other investing and financing activities. This definition links to the cash flow statement because we use EBITDA to calculate FFO, which we use as an accrual-based proxy for CFO (cash flow from operations). Generally, this means that any income statement activity whose cash effects have been (or will be) classified as being from operating activities (excluding interest and taxes) are included in our definition of EBITDA. Conversely, income statement activity whose cash effects have been (or will be) classified in the statement of cash flows as being from investing or financing activities is excluded from EBITDA. 44 Corporate and Project Financial Analysis Programme Income Statement Simplified Income Statement • • • • • • • • • • Sales = + = = = = COGS Gross Margin SG&A Other Expenses Other Income EBITDA Depreciation and Amortization EBIT Interest Expense (income) EBT Income Taxes Minority Interest Net Income There is a debate about how to handle other income from nonconsolidated subsidiary companies. One school of thought (McKinsey) is that they should be valued separately since they will have different cost of capital etc. In this case, do not include in EBITDA and remove the asset balance from the invested capital. Must be consistent NOPLAT = EBIT x (1-tax rate) NOPLAT = Net Income + Interest Expense x (1-tax) 46 Analysis of Income Statement – Computation of EBITDA, Minority Interest, Preferred Dividends, Exploration Expense 47 Corporate and Project Financial Analysis Programme Cash Flow Statement Cash Flow Statement • Modern Cash Flow Statement has separation between – Operations – Capital expenditures (to maintain and grow operations) and – Financing • Operating Cash Flow – Add back items from the income statement that do not use cash (depreciation, dry hole costs etc.) • Analyze how much cash flow the company generated and how it raised funds or disposed funds • Use Cash Flow statement as a basis to compute free cash flow although cash flow not presented on the statement • Problem: Interest Expense – related to financing and not operations – is in the Net Income and is included in Cash From Operations 49 Cash Flow Statement • A. Operating Cash Flows • 1) Net Income including interest expense, interest income and taxes • 2) Depreciation • 3) Deferred Taxes • 4) Working Capital Changes • 5) Minority Interest on Income Statement and Other Items • B. Investing Cash Flows • 1) Capital Expenditure and Asset Purchases • 3) Sale of Property, Plant, & Equipment • 4) Inter-Corporate Investment • C. Financing Cash Flows • 1) Dividend Payments • 3) Proceeds from Equity or Debt Issuance • 4) Equity Repurchased • 5) Debt Principal Payments 50 Cash Flow Statement Items that You Really Need • Depreciation expense if it is not already in the profit and loss statement • Capital expenditures • Maintenance capital expenditures (these are not normally reported) • Dividends (for computing the dividend payout ratio) 51 S&P and Funds from Operations versus EBITDA • Funds form Operations = Net Income from Continuing Operations + Depreciation and Amortization + Deferred Tax + Other Non-Cash Items • Free Operating Cash Flow = FFO + (-) Increase in Working Capital excluding changes in case • Reconciliation of FFO and EBITDA – EBITDA is NI + depreciation + interest + taxes – FFO is NI + depreciation – Difference is interest and taxes 52 Debt Repayment from EBITDA Analysis • Cash Flow that is available to really pay debt service – Begin with EBITDA – Subtract working capital changes required to support EBITDA – Subtract maintenance expenditures required to keep up equipment – Reduce by taxes – Account for Reduction in EBITDA from asset retirement • Use Model with Cash Flow Analysis • Create Data Table to Evaluate Debt to EBITDA 53 Evaluation of EBITDA in Credit Analysis – Assessment of EBITDA in Different Analyses • Sufficient to Repay all Debt in Project Finance Analysis • Sufficient to Generate Financial Ratios for Refinance in Corporate Analysis • Sufficient to Limit Draws from Revolver in Acquisition Analysis – EBITDA Break-even • Potential Reductions in EBITDA • Probability of Default • Loss on Debt 54 Short-term Cash Flow Analysis and Liquidity • Seasonality versus trends in cash flows relative to current assets and current liabilities • Fixed and Variable Costs: how changes in revenues impact profit • Cash Flows and revolving credit facilities – Managing the working capital cycle Business cycles and businesses • Stocking • Selling • Destocking • Applying and evaluating the main ratios to understand and analyse – the Cash Conversion Cycle – the cash position of the business • the credit-worth of the business 55 Corporate and Project Financial Analysis Programme Balance Sheet Balance Sheet Adjustments • When analysing the balance sheet, various items should be adjusted and grouped together: – Net Debt • Total short and long term debt minus liquid investments held and surplus cash – Cash Bucket • For modelling, subtract short-term debt from surplus cash and liquid investments – Surplus Cash • Include temporary investments and also include long-term investments – Current Assets and Current Liabilities • Separate the surplus cash from current assets and the debt from current liabilities and relate remaining working capital items to revenue and expense items 57 Balance Sheet Issues • Treat surplus cash as negative debt and debt as negative cash – Rule of thumb – cash is 2% of revenues – Example – when developing a basic cash flow model, group the cash and the debt as one account and then separate this account on the balance sheet. – Unfunded pension expenses should be treated like debt – they involve a fixed obligation and they can be replaced with debt when they are funded. – Deferred taxes depend on the way deferred taxes are modelled for cash flow purposes. If you model future changes in deferred taxes and take account of these in projections, do not put deferred taxes as a component of equity. 58 Problems with Equity Balance • Would like the return on equity and the return on invested capital to measure equity invested by shareholders for return on investment and return on equity – Problems with using equity balance on the balance sheet to measure equity investment • • • • • Write-offs of plant Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income Goodwill Re-structuring losses Employee Stock options – Can make adjustments to equity balance 59 Corporate and Project Financial Analysis Programme Financial Ratios for Credit Analysis Liquidity and Solvency Credit worthiness: Ability to honor credit obligations (downside risk) Solvency Ability to meet long-term obligations Focus: • Long-term economic risks conditions • Long-term cash flows • Extended ability to make profit Liquidity Ability to meet short-term obligations Focus: • Current Financial conditions • Current cash flows • Liquidity of assets 61 Solvency Ratios • Ratios are the center of traditional credit analysis that assesses whether a company can re-pay loans. These ratios should be compared to benchmarks. • Debt Payback Ratios (Time to Repay) – Funds from Operations to Total Debt – Debt to EBITDA • Leverage Ratios (Skin in the Game) – Debt to Capital (Include Short-term Debt) – Market Debt to Market Capital • Payment Ratios (Buffer for Downside Repayment) – Interest Coverage – Debt Service Coverage [Cash Flow/(Interest + Principal)] 62 Liquidity • Current Ratio – Current Assets to Current Liabilities – Current Assets less Inventory to Current Liabilities • Model Working Capital – Current Assets less Cash and Temporary Securities minus Current liabilities less Short-term Debt • Liquidity Assessment – Debt Profile (Maturities) – Bank Lines (Availability, amount, maturity, covenants, triggers) – Alternative Sources of Liquidity (Asset sales, dividend flexibility, capital spending flexibility) 63 Philosophy and Alternative Calculations for Debt Service and Interest Coverage Ratio • The specifics of the ratios are less important than the general objective and the underlying philosophy of the ratios • The general idea is to see how low EBITDA or cash flow can go down before the debt service or interest cannot be paid • For project finance use DSCR because debt service is known from structuring debt repayments around cash flow • DSCR much less relevant in corporate finance because of bullet debt repayments 64 DSCR Criteria in Different Industries in Project Finance • • • • • • Electric Power: 1.3-1.4 Resources: 1.5-2.0 Telecoms: 1.5-2.0 Infrastructure: 1.2-1.6 Minimum ratio could dip to 1.5 At a minimum, investment-grade merchant projects probably will have to exceed a 2.0x annual DSCR through debt maturity, but also show steadily increasing ratios. Even with 2.0x coverage levels, Standard & Poor's will need to be satisfied that the scenarios behind such forecasts are defensible. Hence, Standard & Poor's may rely on more conservative scenarios when determining its rating levels. • For more traditional contract revenue driven projects, minimum base case coverage levels should exceed 1.3x to 1.5x levels for investment-grade. 65 Debt to Capital Ratio • The debt to capital ratio has two general ideas – The amount of investment made by equity holders – they would not be stupid enough to put skin in the game if they did not expect to be paid – The amount by which the net assets of the company can fall before which the value of the debt will be below the collateral value • Problems with debt ratio is that it depends on the valuation of assets on the balance sheet – Example of goodwill and mergers – Example of stock price assumptions in mergers 66 Philosophy Behind Debt to EBITDA and FFO to Debt • General philosophy is to compute the amount of time that it takes to repay debt. • Debt to EBITDA does not really measure to years of EBITDA to repay debt – Must account for interest – Must account for replacement capital expenditures – Must account for maintenance capital expenditures – Does not account for asset life • FFO to Debt – Accounts for interest – Does not account for other flaws 67 Banks or Rating Agencies Value Debt with Risk Classification Systems Map of Internal Ratings to Public Rating Agencies Internal Credit Ratings 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Code Meaning A Exceptional B Excellent C Strong D Good E Satisfactory F Adequate G Watch List H Weak I Substandard L Doubtful N In Elimination S In Consolidation Z Pending Classification Corresponding Moody's Aaa Aa1 Aa2/Aa3 A1/A2/A3 Baa1/Baa2/Baa3 Ba1 Ba2/Ba3 B1 B2/B3 Caa - O 68 General S&P Benchmarks without Industry or Company Risk Adjustments 69 Financial Ratios and Ratings - Updated 70 Ratios Depend on the Business Risk 71 Credit Rating Standards and Business Risk Business Risk/Financial Risk —Financial risk profile— Business risk profile Minimal Modest Intermediate Aggressive Highly leveraged Excellent AAA AA A BBB BB Strong AA A A- BBB- BB- Satisfactory A BBB+ BBB BB+ B+ Weak BBB BBB- BB+ BB- B Vulnerable BB B+ B+ B B- Financial risk indicative ratios* Minimal Modest Intermediate Aggressive Highly leveraged Cash flow (Funds from operations/Debt) (%) Over 60 45–60 30–45 15–30 Below 15 Debt leverage (Total debt/Capital) (%) Below 25 25–35 35–45 45–55 Over 55 Debt/EBITDA (x) <1.4 3.0–4.5 >4.5 1.4–2.0 2.0–3.0 Key Industry Characteristics And Drivers Of Credit Risk Credit risk impact: High (H); Medium (M); Low (L) Risk factor Industry Airlines (U.S.) Autos* Auto suppliers* High technology* Mining* Chemicals (bulk)* Hotels* Shipping* Competitive power* Telecoms (Europe) Cyclicality H H H H H H H H H H M Competition H H H H H H H H H H H Capital intensity Technology risk H L H M H M M H H M H L H L H L H L M L H H Regulatory/Gov ernment M/H M M L M/H M M L L H H Energy sensitivity H H M L/M H L H M M H L 72 S&P Use of Ratios and Business Risk Profile to Determine Credit Risk Business Risk/Financial Risk Business risk profile Excellent Strong Satisfactory Minimal AAA AA A Modest AA A BBB+ Intermediate A ABBB Aggressive BBB BBBBB+ Highly leveraged BB BBB+ Weak Vulnerable BBB BB BBBB+ BB+ B+ BBB B B- Financial risk indicative ratios* Cash flow (Funds from operations/Debt) (%) Debt leverage (Total debt/Capital) (%) Debt/EBITDA (x) Minimal Over 60 Below 25 <1.4 Modest 45–60 25–35 1.4–2.0 Intermediate 30–45 35–45 2.0–3.0 Aggressive 15–30 45–55 3.0–4.5 Highly leveraged Below 15 Over 55 >4.5 FFO to Debt Debt to EBITDA Debt to FFO 60.00% 1.40 1.67 52.50% 1.70 1.90 37.50% 2.50 2.67 22.50% 3.75 4.44 15.00% 4.50 6.67 73 Example of Using Ratios to Gauge Credit Rating • The credit ratios are shown next to the achieved ratios. Concentrate on Funds from operations ratios. Note that based on business profile scores published by S&P 74 Debt Capacity and Interest Cover • Despite theory of probability of default and loss given default, the basic technique to establish bond ratings continues to be cover ratios. • This analysis from Damarodan is not correct because it does not account for business conditions. 75 Computing Simulated Bond Ratings from Financial R atios Use File with S&P Bond Ratings Enter the financial ratio Then enter the business risk 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Use excel functions: INDEX MATCH LOOKUP INTERPOLATE INTERPOLATE REVERSE Ratio Business Risk Row Number Low Range High Range Interpolated Bond Rating Interpolated Lowest FFO/Interest Acceptable 1 2 3 AA A BBB 2.50 1.50 1.00 3.00 2.00 1.00 3.50 2.50 1.50 4.20 3.50 2.50 4.50 3.80 2.80 5.20 4.20 3.00 6.50 4.50 3.20 7.50 5.50 3.50 7.00 4.00 2.80 5.61 5.00 4.50 5.20 4.92 BB 3.12 5.61 5.00 3.80 4.20 4.04 5.61 5.00 2.80 3.00 2.92 4 BB 1.00 1.50 1.80 2.00 2.20 2.50 2.80 5.61 5.00 1.80 2.00 1.92 76 DSCR and Credit Ratings in Project Finance • Target rating of BBB• Target DSCR or LLCR • Example of Toll-roads 77 Default Rates and Credit Spreads 78 Moody’s Forecast of Default Rates Defaults versus Long-term Average Moody's Speculative Grade Trailing 12-Month Default Rates Actual Jan. 2000 to Aug. 2002 / Forecasted Sept. 2002 to Feb. 2003 12.0% 11.0% 10.5% 9.6% 10.0% 9.0% 8.5% 7.7% 8.0% 7.0% 7.7% 8.8% 10.7% 10.5% 10.3% 10.3% 10.5% 10.3% 9.8% 10.1% 10.0% 10.0% 10.0% 10.0% 9.8% 9.3% 9.0% 8.8% 7.9% 7.1% 6.7% 6.2% % 6.0% 5.0% 4.0% 3.77%* 3.0% 2.0% 1.0% Feb-03 Jan-03 Dec-02 Nov-02 Oct-02 Sep-02 Aug-02 Jul-02 Jun-02 May-02 Apr-02 Mar-02 Feb-02 Jan-02 Dec-01 Nov-01 Oct-01 Sep-01 Aug-01 Jul-01 Jun-01 May-01 Apr-01 Mar-01 Feb-01 Jan-01 0.0% Months Note: *Long run annual default rate is 3.77% 79 Probability of Default • This chart shows rating migrations and the proba bility of default for alternative loans. Note the in crease in default probability with longer loans. 80 Probability of Default Updated 81 Credit Spread on Debt Facilities • The spread on a loan is directly related to the probability of default andS the loss, given default. The Credit Triangle S = P (1-R) P R The credit spread (s) can be characterized as the default probability (P) times the loss in the event of a default (R). 82 Expected Loss Can Be Broken Down Into Three Components Borrower Risk EXPECTED LOSS $$ = Probability of Default Facility Risk Related Loss Severity x Given Default Loan Equivalent x Exposure (PD) (Severity) (Exposure) % % $$ What is the probability of the counterparty defaulting? If default occurs, how much of this do we expect to lose? If default occurs, how much exposure do we expect to have? The focus of grading tools is on modeling PD 83 Comparison of PD x LGD with Precise Formula Case 1: No LGD and One Year • . 84 Comparison of PD x LGD with Precise Formula Case 2: LGD and Multiple Years • . Assumptions Years Risk Free Rate 1 Prob Default 1 Loss Given Default 1 5 5% 20.8% 80% BB 5 7 20.80% PD Alternative Computations of Credit Spread Credit Spread 1 3.88% PD x LGD 1 16.64% Proof Opening 100 Closing 127.63 Value 127.63 Risky - No Default 100 Prob Closing 0.95 153.01 Value 145.36 Risky - Default 100 Risk Free Total Value 0.05 30.60 1.53 146.89 FALSE Credit Spread Formula With LGD cs = ((1+rf)/((1-pd)+pd*(1-lgd))-rf)^(1/years)-1 85 Recovery Rates 86 Putting Things Together and Measuring the Risk Adjusted Return on Capital 87 Corporate and Project Financial Analysis Programme Determining the Correct Ratio to Use in Measuring Profit Relevance of Measuring Profit for Credit Analysis • Some would say that the credit ratios are more important, but if there is no profit, there is no ability to repay debt • Long-term profitability should be assessed • The most important item is the danger of high rates of return – Attract competitors – Attract political risk – Artificially inflated – Subject to changes in tastes 89 Financial Indicators of Management Performance • Evaluate Whether Management is Doing a Good Job with Investor Funds (Not if the company is appropriately valued) – Return on Invested Capital – Return on Assets – Return on Equity – Market/Book Ratio – Market Value/Replacement Cost • Key Issue – Evaluate relative to risk • ROE versus Cost of Equity • ROIC versus WACC 90 Basic Economic Principles, ROIC and Financial Analysis • When you measure value, you are gauging the ability of a firm to realize economic profit. For example, when you compare the equity IRR with the equity cost of capital. • When you assess assumptions in a financial forecast, you must assess whether economic profit implicit in the assumptions can in fact be realized. For example, if the financial forecast has a very high ROE, is that reasonable. • When you interpret financial statistics, you are gauging the strategy of the company in terms of whether economic profit is being realized. In reviewing the return on invested capital, does this demonstrate that the company has the potential to earn economic profit. 91 Return on Invested Capital Analysis • ROIC is not distorted by the leverage of the company • ROIC can be used to gauge economic profit and whether the company should grow operations • ROIC can be used to assess the reasonableness of projections – For example, if ROIC is very high and the company is in a competitive business with few barriers to entry, the forecast is probably not realistic. • ROIC can be computed on a division basis EBIT and allocation of capital to divisions from net assets to gauge the profit of parts of the company • ROIC comes from sustainable competitive advantage and high market share 92 Issues in Management Performance Evaluation • Basic Formula: ROIC versus WACC – How to compute ROIC • NOPLAT/Average Invested Capital • May or may not include goodwill – If goodwill is not included, compute NOPLAT without subtracting goodwill write-off and subtract net goodwill from invested capital • Reduce the invested capital by surplus cash balances • Some don’t include other income – then the invested capital should be reduced by other investments • Can compute with ratios – EBIT Margin x (1-t) * Asset Turn – Asset Turn = Sales/Assets; EBIT Margin = EBIT/Sales – ROCE vs. ROIC • ROCE is generally computed in an indirect way by starting with net income, and adding net of tax interest and adding minorities 93 Exxon Mobil Return on Average Capital Employed • Return on average capital employed (ROCE) is a performance measure ratio. From the perspective of the business segments, ROCE is annual business segment earnings divided by average business segment capital employed (average of beginning and end-of-year amounts). • These segment earnings include ExxonMobil’s share of segment earnings of equity companies, consistent with our capital employed definition, and exclude the cost of financing. • The corporation’s total ROCE is net income excluding the after-tax cost of financing, divided by total corporate average capital employed. The corporation has consistently applied its ROCE definition for many years and views it as the best measure of historical capital productivity in our capital intensive long-term industry, both to evaluate management’s performance and to demonstrate to shareholders that capital has been used wisely over the long term. Additional measures, which tend to be more cash flow based, are used for future investment decisions. 94 Exxon Mobil Return on Capital Employed – Where are they making expenditures 95 Illustration of Invested Capital Computation 96 ROE and ROIC – Note how to compute growth rates from ROE and Retention 97 Corporate and Project Financial Analysis Programme Financial Statement Analysis Liquidity, Solvency and Efficiency Analysis Evaluation of Ratios and Understanding Problems with Ratios • Importance of Different Ratios – Limited use of liquidity ratios in long-term loans – Problems with Debt to EBITDA and re-investment requirement in capital expenditures – Problems with Interest Coverage and Repayment of Debt – Problems with Debt to Capital and asset valuation on balance sheet – Problems with Return on Investment with write-offs, restructuring charges, asset sales 99 Limited use of liquidity ratios in long-term loans • Accounts Receivable in different industries such as telecom • Valuation of inventories • Cash and need for debt 100 Problems with Debt to EBITDA • • • • • Variation in EBITDA Accounting for Asset Life Reflecting Maintenance capital expenditures Measuring Interest Expense Case Study: Chesapake Energy 101 Problems with Interest Coverage and Repayment of Debt • Directly measures acceptable variation in EBITDA • If the lifetime of assets is 5-years, must somehow a ccount for the repayment over the lifetime of assets • Use of LLCR and PLCR in project finance 102 Use of Different Ratios in Different Circumstances • Explain why different ratios are typically applied: – DSCR and LLCR in Project Finance with Contracts • Break even cash flow • Toll road cash flow patterns – PLCR in Project Finance In Resource Projects • Break-even commodity price over reserve life – Debt to EBITDA in Leverage Buyouts • Relates to EV/EBITDA – Debt to Capital in Stable Industries with Market Based Asset Value – Interest Coverage in Highly Levered Transactions with Cash Sweep 103 Items that Distort Financial Ratios • Issues that Distort Financial Ratios – Goodwill in Merger Transaction – Share Valuation in Exchange Transaction – Maintenance Expenditures in Debt to EBITDA – Asset Impairment for Debt to Capital – Re-structuring Charges 104 Corporate and Project Financial Analysis Programme Analyzing Statement of Other Comprehensive Income Valuation of Derivatives • Example of Forward Contract – Example of Oil Price Contract – Term and Futures Price – Valuation when Forward Price Changes over Time • Example of Interest Rates – Valuation of Debt with Changing Interest Rates – Valuation of Interest Rate Swap • Example of Option – Using the Black Sholes Model – Valuation of Band of Oil Prices 106 Accounting for Changes in Value of Derivatives • Hedge Accounting versus Direct – No effect on income statement if hedge accounting • Example of oil price hedge – Gains in value in profit and loss • Should or should not be in be in EBITDA? – Effects of income and investment on • ROIC • Debt to Capital • Debt to EBITDA 107 Unrealized gains or losses on derivatives (S&P) • If a company has not achieved the requirements of technical hedge accounting (even though an effective economic hedge may exist), it reports all mark-to-market gains or losses related to the fair-valuing of derivative contracts in the income statement. • Although the nature of the underlying activity is often integral to EBITDA, FFO, or both, using mark-to-market accounting can distort these metrics because the derivative contract may be used to hedge several future periods. Therefore, when we have sufficient information, we exclude the unrealized gains or losses not related to current-year activity, so that the income statement represents the economic hedge position achieved in the current financial year (that is, as if hedge accounting had been used). • This adjustment is common in the utilities and oil and gas sectors. This means that hedge accounting does not result in EBITDA being affected by the hedges. 108 Case Study of Problems with Derivatives – Constellation Energy Constellation Merchant Segments Reported in 2009 ($ millions) 2006 2007 2008 Gross margin: Generation Customer Supply Global Commodities 1,490 764 656 1,700 889 654 1,956 765 260 Total 2,910 3,243 2,981 Generation Percent 51% 52% 66% Valuation by Morgan Stanley Low Range High Range Fair value of businesses other than global commodities $12,000.00 $13,000.00 Less repayment of outstanding indebtedness ($6,000.00) ($6,000.00) Less net loss (negative value) of global commodities business ($2,000.00) ($2,000.00) Net equity value (before costs and expenses) $4,000.00 $5,000.00 Shares 179.00 179.00 Net equity value per share (before costs and expenses) $22.35 $27.93 109 Effects of Derivative Accounting • Constellation Energy had stated that it was hedged. But: – $282 million of lower gross margin related to our portfolio of contracts subject to mark-to-market accounting. – On October 31, 2008, we discontinued the use of hedge accounting for derivative contracts that previously were accounted for as cash-flow hedges within the international commodities operation. From that date, subsequent changes in fair value of those derivative contracts have been recorded in earnings. We concluded that the combination of the decline in value associated with the previously hedged transactions together with the related balances remaining in accumulated other comprehensive income, would lead to the recognition of a net loss in one or more future periods. As such, we recognized a loss of $42 million during the fourth quarter of 2008. 110 Re-valuations of Assets and Liabilities • Evaluating sensitivities for FX gains and losses • Property: identifying cash and non-cash gains and losses in value • Hedging gains and losses: when do financial asset revaluations impact the Income statement? 111 General Discussion of Profit and Distributions • Consolidated net profit • Funding dividends and distributions in alternative financial structures • Dividend policy and capital structure • Dividends as mitigation in credit analysis 112 Shareholder Loans • Effects of shareholder loans on ability to pay dividends • Effects on taxes of corporation • Effects on taxes paid by debt and equity investors • Analyzing a share buyback’s impact on EPS and NAV 113 Corporate and Project Financial Analysis Programme Assessing Earnings Quality Premature revenue recognition • Examples – WorldCom • Caused bankruptcy • Revenue instead of capital – Mobily • Pre-paid accounts • Resulted in Major Stock Decline – Enron • Recognized Future Revenues on Contracts • Allowance for doubtful accounts 115 Projecting and Analyzing Revenues • Price vs. volume changes – Often difficult from financial statements – Requires industry data – Danger of price and volume growth • • • • • • Evaluation of price with marginal cost analysis Potential for prices to decline to short-run marginal cost Difficulty in projecting volumes for oligopoly Real and nominal growth Price versus margin analysis Exercise with Simulation Model 116 Evaluating Costs and Discretionary Expenditures • Cost flow assumption for inventory – – – – Inventory restructuring (LIFO pools) Inventory write downs and effect on gross margin Shifting future expenses to the current period - provisioning Identifying and adjusting for Inflation profits in inventory • Analysing and evaluating the impact of – capitalisation of expenses (World com) – changing depreciation over (in)-appropriate periods (Shale o il and gas) – deferring expenses – asset impairment and accelerated depreciations 117 Boosting Profits and Hiding Negative Trends • Motivations – Declining returns relative to past – Declining returns relative to peers • Techniques to hide problems – Use sophisticated and confusing language – Increase gearing and hide debt – Capitalise future profits – Combine risky activities with safe activities 118 Case Studies of Boosting Profits and Hiding Negative Returns • Constellation Energy – Sophisticated language – Lenders lose confidence and cannot re-finance – Stock price decline – VAR does not work • LTCM – Famous case of hedge fund – Returns declined after methods copied – Increased leverage – Took risky positions instead of arbitrage 119