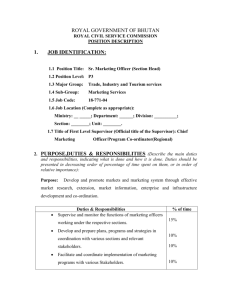

BEO-2012-Zero-Draft-working-file_PK_2_Jan

advertisement