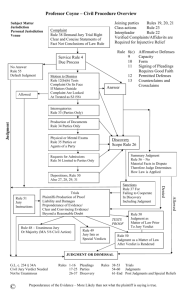

Chase, Civil Procedure, Fall 2011

advertisement