the Slides Only - American Academy of Pediatrics

advertisement

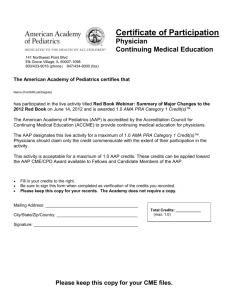

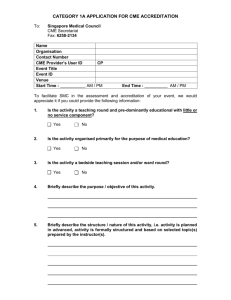

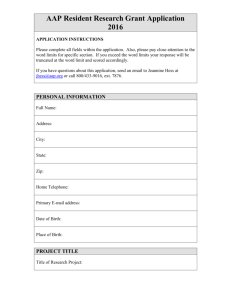

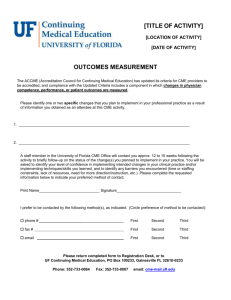

The Role of Health Information Technology in Medication Safety Wednesday, April 25, 2007 12:00 – 1:00 p.m. EDT Moderator: Paul Sharek, MD, MPH, FAAP Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Stanford School of Medicine Medical Director of Quality Management Chief Clinical Patient Safety Officer Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Palo Alto, California This activity was funded through an educational grant from the Physicians’ Foundation for Health Systems Excellence. Disclosure of Financial Relationships and Resolution of Conflicts of Interest for AAP CME Activities Grid The AAP CME program aims to develop, maintain, and increase the competency, skills, and professional performance of pediatric healthcare professionals by providing high quality, relevant, accessible and cost-effective educational experiences. The AAP CME program provides activities to meet the participants’ identified education needs and to support their lifelong learning towards a goal of improving care for children and families (AAP CME Program Mission Statement, August 2004). The AAP recognizes that there are a variety of financial relationships between individuals and commercial interests that require review to identify possible conflicts of interest in a CME activity. The “AAP Policy on Disclosure of Financial Relationships and Resolution of Conflicts of Interest for AAP CME Activities” is designed to ensure quality, objective, balanced, and scientifically rigorous AAP CME activities by identifying and resolving all potential conflicts of interest prior to the confirmation of service of those in a position to influence and/or control CME content. The AAP has taken steps to resolve any potential conflicts of interest. All AAP CME activities will strictly adhere to the 2004 Updated Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) Standards for Commercial Support: Standards to Ensure the Independence of CME Activities. In accordance with these Standards, the following decisions will be made free of the control of a commercial interest: identification of CME needs, determination of educational objectives, selection and presentation of content, selection of all persons and organizations that will be in a position to control the content, selection of educational methods, and evaluation of the CME activity. The purpose of this policy is to ensure all potential conflicts of interest are identified and mechanisms to resolve them prior to the CME activity are implemented in ways that are consistent with the public good. The AAP is committed to providing learners with commercially unbiased CME activities. DISCLOSURES Activity Title: Activity Date: Safer Health Care for Kids - Webinar The Role of Health Information Technology in Medication Safety April 25, 2007 DISCLOSURE OF FINANCIAL RELATIONSHIPS All individuals in a position to influence and/or control the c ontent of AAP CME activities are required to disclose to the AAP and subsequently to learners that the individual either has no relevant financial relationships or any financial relationships with the manufacturer(s) of any commercial product(s) and/or pro vider of commercial services discussed in CME activities. Name Rainu Kaushal, MD, MPH Name of Commercial Interest(s)* (*Entity producing health care goods or services) Nature of Relevant Financial Relationship(s) (If yes, please list: Research Grant, Speaker’s Bureau, Stock/Bonds excluding mutual funds, Consultant, Other - identify) CME Content Will Include Discussion/ Reference to Commercial Products/Services Disclosure of Off-Label (Unapproved)/Investigational Uses of Products AAP CME faculty are required to disclose to the AAP and to learners when they plan to discuss or demonstrate pharmaceuticals and/or medical devices that are not approved No No No No DISCLOSURES SAFER HEALTH CARE FOR KIDS - PROJECT ADVISORY COMMITTEE AND STAFF DISCLOSURE OF FINANCIAL RELATIONSHIPS All individuals in a position to influence and/or control the content of AAP CME ac tivities are required to disclose to the AAP and subsequently to learners that the individual either has no relevant financial relationships or any financial relationships with the manufacturer(s) of any commercial product(s) and/or provider of commercial services discussed in CME activities. Name Name of Commercial Interest(s)* (*Entity producing health care goods or services) Nature of Relevant Financial Relationship(s) (If yes, please list: Research Grant, Speaker’s Bureau, Stock/Bonds excluding mutual funds, Consultant, Other - identify) CME Content Will Include Discussion/ Reference to Commercial Products/Services Disclosure of Off-Label (Unapproved)/Investigational Uses of Products AAP CME faculty are required to disclose to the AAP and to learners when they plan to discuss or demonstrate pharmaceuticals and/or medical devices that are not approved Karen Frush, MD, FAAP (PAC Member) No No No No Uma Kotagal, MD, MBBS, MSc, FAAP (PAC Member) No No No No Christopher Landrigan, MD, MPH, FAAP (PAC Member) No No No No Marlene R. Miller, MD, MSc, FAAP (PAC Chair) No No No No Paul Sharek, MD, MPH. FAAP (PAC Member) No No No No Erin Stucky, MD, FAAP (PAC Member) No No Not sure No Nancy Nelson (AAP Staff) No No No No Melissa Singleton, MEd (Project Manager – AAP Consultant) No No No No Junelle Speller (AAP Staff) No No No No Linda Walsh, MAB (AAP Staff) No No No No DISCLOSURES AAP COMMITTEE ON CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION (COCME) DISCLOSURE OF FINANCIAL RELATIONSHIPS All individuals in a position to influence and/or control the content of AAP CME ac tivities are required to disclose to the AAP and subsequently to learners that the individual either has no relevant financial relationships or any financial relationships with the manufacturer(s) of any commercial product(s) and/or provider of commercial services discussed in CME activities. Name Name of Commercial Interest(s)* (*Entity producing health care goods or services) Nature of Relevant Financial Relationship(s) (If yes, please list: Research Grant, Speaker’s Bureau, Stock/Bonds excluding mutual funds, Consultant, Other - identify) CME Content Will Include Discussion/ Reference to Commercial Products/Services Disclosure of Off-Label (Unapproved)/Investigational Uses of Products AAP CME faculty are required to disclose to the AAP and to learners when they plan to discuss or demonstrate pharmaceuticals and/or medical devices that are not approved Ellen Buerk, MD, FAAP No No No No Meg Fisher, MD, FAAP No No No No Robert A. Wiebe, MD, FAAP No No Not sure No Jack Dolcourt, MD, FAAP No No No No Thomas W. Pendergrass, MD, FAAP No No No No Beverly P. Wood, MD, FAAP No No No No CME CREDIT The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical education for physicians. The AAP designates this educational activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™. Physicians should only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity. This activity is acceptable for up to 1.0 AAP credit. This credit can be applied toward the AAP CME/CPD Award available to Fellows and Candidate Fellows of the American Academy of Pediatrics. OTHER CREDIT This webinar is approved by the National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners (NAPNAP) for 1.2 NAPNAP contact hours of which 0.3 contain pharmacology (Rx) content. The AAP is designated as Agency #17. Upon completion of the program, each participant desiring NAPNAP contact hours should send a completed certificate of attendance, along with the required recording fee ($10 for NAPNAP members, $15 for nonmembers), to the NAPNAP National Office at 20 Brace Road, Suite 200, Cherry Hill, NJ 08034-2633. The American Academy of Physician Assistants accepts AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)TM from organizations accredited by the ACCME . Rainu Kaushal, MD, MPH Associate Professor of Pediatrics and Public Health, Weill Medical College of Cornell University Director of Pediatric Quality and Safety, KCCH at NYPH New York, New York The Role of Health Information Technology in Medication Safety April 25, 2007 12:00 – 1:00 p.m. EDT 11 Learning Objectives Upon completion of this activity, you will be able to: Review the epidemiology of ambulatory medication safety in pediatrics. Describe the role of health information technology in improving medication safety. Utilize specific health information technology applications. 12 Historical Perspective In 1925, 4 main types of adverse events identified for hospitalized patients: Burns due to hot water Delirious patients jumping from hospital windows Accidents connected with hospital elevators Mistakes in the use of drugs Aikens C. Study in the Ethics for Nurses. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1925 13 Patient Safety and Medical Errors Become a National Concern November 29, 1999 14 15 IOM Report: Preventing Medication Errors One medication error per day per inpatient Variation across institutions At least 25% of injuries from medications are preventable Annual preventable injuries from medications 380,000-450,000 in hospitals for $3.5 billion 800,000 in long-term care 530,000 in Medicare ambulatory patients for $887 million 16 Preventing Medication Errors: Recommendations Patient’s rights and enhancing consumer information Utilizing HIT Prescribing and transmission of all prescriptions electronically by 2010 Appropriate clinical decision support Adopt other appropriate technology (eMAR, bar coding, smart iv pumps) Monitor for medication errors Standards for HIT More research 17 Pediatrics a prime focus area Overview Why medication errors occur in children Pediatric medication error epidemiology Inpatient Outpatient Prevention strategies HIT Safety and quality Financial 18 Why medication errors occur in children Weight based dosing Stock medicine dilution Ten fold errors Decreased communication abilities Inability to self-administer medications Increased vulnerability of young, critically ill children Immature renal and hepatic systems 19 Definitions Medication Errors ADEs Near Misses 20 Comparisons of Adult and Pediatric Inpatients Pediatrics Orders reviewed Medication errors Near Misses ADEs Preventable ADEs 10,778 616 (5.7%) 115 (1.1%) 26 (0.24%) 5 (0.05%) Adults** 10,070 530 (5.3%) 35 (0.35%) * 25 (0.25%) 5 (0.05%) *p value <0.05 **Study performed at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in 1992 using similar methods Kaushal et al, JAMA 2001 21 Error Stage for Medication Errors Ordering 74% Transcribe 10% Dispense 13% Administer 2% Monitor 1% 22 Near Misses in the NICU per 100 orders 3 2.8 2.5 2 1.5 1.3 * 1 0.77 * 0.5 0.35 * 0 NICU JAMA 2001;285;2114-20 PICU Med/Surg Adult * P<0.001 23 Ambulatory Setting: Medication Errors 2952 medication errors 1.6 errors per patient 1.3 errors per prescription 521 (12%) rx inappropriate abbreviation 1389 (64%) rx partially illegible Weight Other Dose Route Amount Strength 24 Preliminary Results For Six Office Practices Rate N 95% CI 3% 57 3-4 Non-preventable ADEs 13% 226 11-15 Ameliorable ADEs 9% 152 7-10 Non-intercepted Near Misses 25% 455 22-29 Preventable ADEs 25 Stages Preventable ADEs Administering Ordering Dispensing Transmitting Near Misses Administering Ordering Dispensing Transmitting 26 Why Do Errors Occur? Physician writes an order Nursing, pharmacist, and clerical staff mechanisms are in place to carry out orders What occurs in reality? 27 We deliver medications in hospitals in a manner that essentially hasn’t changed in 60 years. pharmacist checks nurse checks patient, physician writes order order/allergies drug, dose, route, time nurse administers pharmacist checks secretary transcribes drug drug interactions Is a double check pharmacy tech loads nurse double checks necessary? drawer pharmacy tech places Is drug administered secretary faxes drawer in delivery system via pump pharmacist receives nurse obtains drug fax from delivery system If order incorrect: pharmacist enter nurse checks drug multiple other steps order against med sheets 28 We deliver medications in hospitals in a manner that essentially hasn’t changed in 60 years. pharmacist checks nurse checks patient, physician writes order order/allergies drug, dose, route, time nurse administers pharmacist checks secretary transcribes drug drug interactions Is a double check pharm. tech loads nurse double checks necessary? drawer pharm. tech places Is drug administered secretary faxes drawer in meditrol via pump pharmacist receives nurse obtains drug fax from meditrol If order incorrect: pharmacist enter nurse checks drug multiple other steps order against med sheets 29 The Role of Complexity in Preventing Errors Probability of Performing Perfectly: Probability of success, each element: # of elements 0.95 1 25 50 100 0.95 0.28 0.08 0.006 0.99 0.99 0.78 0.61 0.37 0.999 0.999 0.96 0.95 0.90 0.9999 0.9999 0.998 0.995 0.99 30 No one makes an error on purpose. Lucian Leape 31 Everyone makes dumb mistakes every day. 32 No one admits an error if you punish them for it. 33 Error Reduction: Systems Approach Culture of Safety Non-punitive systems Multidisciplinary error prevention Involve parents and families Executive walk rounds Medication Safety Initiative Strong, clear, visible attention to safety Avoid fatigue Minimize distractions Independent double checks nd checker will detect ~ 90% of errors made by 2 first checker HIT 34 How will HIT help? Improve communication What has been done and by whom Improve accessibility Paper records unavailable 1/3 of the time Physicians spend 20-30% of their time searching for and organizing information Require key pieces of information Improve information retrieval Impossible to store all needed clinical information in a physician’s head 35 How will HIT help? (cont) “Just in time” decision support Assist with calculations Make the right thing the easiest to do Perform checks in real-time Assist with monitoring Advance the quality agenda Quality measurement Low cost way to diffuse evidence-based best practices 36 Impact of HIT on Quality, Efficiency and Costs 4 Benchmark institutions Quality Efficiency Increased adherence to guidelines Enhanced surveillance and monitoring Medication errors Decreased utilization of care Financial Chaudhry B et al, Annals 2006 37 Types of HIT EHR, Electronic health record CPOE, Computerized physician order entry Robots Smart IV systems Bar coding Telemedicine Automated drug delivery systems 38 CPOE: Low hanging fruit Illegible handwriting Incomplete information Unacceptable Abbreviations Lack of leading zeros Inclusion of trailing zeros 39 Key Areas of Decision Support Requiring complete orders Default doses Drug-allergy checking DDI checking Renal dosing Geriatric dosing Drug-lab checking Dose ceilings 40 Handwriting example 41 “Corollary” order reminders reduce errors of omission Target - corollary order pairs (n=87) NSAID – creatinine level Aminoglycoside – drug levels, creatinine Warfarin – routine protimes Intervention -- display reminder at time of ordering Overhage JAMIA 1997;4:364-375 42 Effect of alerts on compliance Overhage JAMIA 1997;4:364-375 43 Proportion of doses exceeding recommended maximum 2.50% 2.10% 2.00% 1.50% 1.00% 0.60% 0.50% 0.00% Paper-based Computer ordering Teich Archives Int Med 2000;160:2741 44 Dosing appropriateness in patients with renal impairment 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% 67% 54% 59% 35% Dose appropriate Intervention Both results P < 0.001 Frequency appropriate Control Chertow JAMA 2001;286:2839-44 45 Effect of an antibiotic advisor 146 160 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 500 405 400 300 35 200 87 100 Orders for drugs to which patient is allergic 250 0 206 Excess drug dosages 30 200 25 150 20 15 100 50 12 0 Antibiotic-susceptibility mismatches All results statistically significant Costs, LOS also reduced Evans NEJM 1998;338:232-238 28 10 5 0 4 ADEs caused by antiinfective agent Intervention Control 46 Effect of Changing Default Dosing Frequency for Ceftriaxone 60 40 BID QD 30 20 10 Week 17 15 13 11 9 7 5 3 0 1 Orders/week 50 NYPH -- Pediatric dosing decision support Computer suggests 300 mg every 8 hours for this patient; based on age and weight Evaluation •32% of suggestions accepted exactly •Good reasons for not following •Subjectively, physicians like it (Killela B, et al; Pediatrics, 2007) 48 Results of Two Studies on Medication Error Prevention CPOE reduced medication errors by 80% CPOE reduced serious medication errors by 55% Bates et al, JAMA 1998 Evidence of Reduction in Errors CPOE Pittsburgh Children’s Harmful ADEs pre-CPOE 0.05/1000 doses Post-CPOE 0.03/1000 doses (p=0.05). CPOE prevents 1 ADE every 64 patient days Upperman et al. J Pediatr Surg 2005;40:57-59 50 Evidence of Reduction in Errors Mullett Stand alone anti-infective CDSS in PICU 59% decrease in the rate of pharmacy interventions for wrong drug doses Potts CPOE and medication ordering errors in PICU Medication errors reduced 96% Near misses reduced 41% Mullett CJ, et al. Pediatrics 2001;108:75-81 Potts AL, et al. Pediatrics 2004;113:59-63 51 So what’s the problem? High federal and state policy interest Leapfrog group identified as 1 of 3 patient safety ‘leaps’ Only 10-15% of hospitals across the country have active CPOE systems Few primary care physicians have CPOE High stakes Enormous institutional investment Well-publicized ‘failures’ 52 Unintended Consequences “I have ordered the test that was right next to the one I thought I ordered, you know, right below it that little thingie had come down and I clicked and I’m lookin’ at this one but I in fact clicked on the thing before. By that time I turned my head and I’m hitting return and typing my signature and not seeing it.” Ash, JAMIA 2005 53 $$$,$$$,$$$ High cost and lack of capital Cost benefit mis-match “The number one [barrier] is cost. I have been doing hospital software for 29 years, and this is the most expensive project I’ve ever done.” “[CPOE] may save a lot of money [for] the health care system overall, but [the money] is not being collected by the hospital.” For ambulatory CPOE, assuming 11.6% capitation rate nationally 11% of ROI accrues to providers 89% to other stakeholders, primarily payers 54 Errors in Administration IV Infusions Rule of 6’s intended for rapid dose calculation and drug preparation If: conc of drug (mL/100 ml) = 6 x patient weight (kg) Then: dose (µg/kg per min) = rate (mL/hour) Calculation intensive Numerous possible concentrations If use standard drug concentrations, then rely on dosing charts 55 Errors in Administration IV Infusions IV syringe pumps Traditional infusion pumps prone to ADEs Errors due to keypad data entry mistakes Free-flow phenomena 56 Smart Pumps Library of medications with standard concentrations specific to patient population Makes calculations “Safety net” Hard limits (range cannot be overridden) Soft limits (can be overridden) Pump alarms and halts infusion if medication dose is programmed outside preset limits 57 Smart Pump with Standard Concentrations and Redesigned Labels 3.5 3 2.5 Reported Errors 2 1.5 1 * 0.5 0 Preintervention Errors, per 1000 doses Larsen et al. Pediatrics 2005 Postintervention Errors, per 1000 doses *p<0.001 58 Safe Practices for Communicating Test Results Critical ambulatory safety issue 75% of physicians did not notify patients of normal results 33% of physicians did not even notify of abnormal results (Boohaker et al, Archives 1996) Approximately 1/3 of women with abnormal mammograms or pap smears do not receive appropriate follow-up care 59 Improving Result Management Systems Can be integrated with Electronic Medical Records A tool that allows focus on truly abnormal test results A tool that warns physicians if patients have missed tests Use of standardized features, such as “ticklers” Paper systems can also be highly successful Standardized procedures rather than every physician doing it his/her own way 60 Results Manager Application 61 Strategy: Automate Carefully EHR CPOE Smart IV systems Robots Automated drug delivery systems Bar coding Inexpensive technology 63% reduction in serious dispensing errors at BWH Conclusions Make safety top priority Move from a culture of blame to one of safety Stop blaming people for making errors To err is human Improve the system Utilize technology as it becomes available Involve patients/parents to the fullest extent Measure and iteratively refine 63