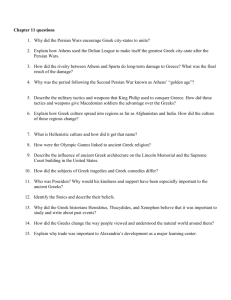

The Contest for Excellence

Greece, 2000-338 B.C.E.

The Contest for Excellence

The Big Picture

Archaic Age Classical Age

Mycenaeans

Minoans

2000 B.C.E.

Colonization

Trojan War

1000 B.C.E.

Peloponnesian War

Persian War

400 B.C.E.

2

The Contest for Excellence

The Big Question

How and why did the Greeks develop a

politics and culture so distinctly different

from the ones that evolved in the Ancient

Middle East?

3

The Rise and Fall of

Ancient Heroes

The Greek Peninsula

THE TOPOGRAPHY OF THE PENINSULA—MOUNTAINOUS WITH

NO LARGE RIVERS—TENDED TO MAKE COMMUNITIES

DEVELOP IN ISOLATION. GREEKS WERE OFTEN ORIENTED

TOWARD THE SEA.

4

The Rise and Fall of

Ancient Heroes

The Minoans, 2000-1450 B.C.E.

– Wealthy and powerful civilization emerges on the island of Crete ca.

2000 B.C.E.

– Not Greek, but a Semitic people.

– Great city of Knossos is best known to us, which probably had roughly

40,000 living there at its height.

– Traded with Fertile Crescent, learned to make Bronze from Sumerians,

and built the best ships.

– Minoan Palaces: Mazes of storerooms, leading to the legend of the

labyrinth and Minotaur . Not symmetrical like most Mesopotamian and

Egyptian architecture.

– Myth of Theseus: The half-man, half-bull may have been the King of

Knossos wearing a bull headress killed by a Greek.

5

The Rise and Fall of

Ancient Heroes

The Minoans, 2000-1450 B.C.E.

Greek representation (ca. 550 B.C.E. of Theseus and the Minotaur):

6

The Rise and Fall of

Ancient Heroes

The Minoans, 2000-1450 B.C.E.

– Developed a pictographic script like Sumerian cuneiform etched in clay

tablets that we call “Linear A,” which scholars have yet to translate, but

appears to have been used for accounting.

– Palaces decorated with brilliantly colored frescoes.

– Religion focused on a fertility goddess depicted holding snakes.

– Religious ritual involved leaping over bulls; may have been an early

precursor to bullfighting, ending with sacrifice.

– Volcanic explosion on Thera (Santorini) may have ended Minoan

civilization around 1450 B.C.E., but scholars debate the timing.

– Whatever happened, the center of Aegean civilization passed to the

Greeks.

7

The Rise and Fall of

Ancient Heroes

The Minoans, 2000-1450 B.C.E.

Fresco of Minoan bull-leaper, ca. 17th to 15th

century B.C.E.; statue of Minoan Snake Goddess,

ca, 1600 B.C.E.

8

The Rise and Fall of

Ancient Heroes

• Mycenaean Civilization: The First

Greeks, 2000-1100 B.C.E.

– Indo-European Greek-speaking people invaded the Greek

peninsula sometime after 2000 B.C.E.

– Excavation of shaft-graves have uncovered crowns and

masks in the Indo-European style.

– Middle Eastern writer referred to these people as the “warmad Greeks” during this period.

– Imitated Minoan art and writing system, creating their own

that we call “Linear B.”

9

The Rise and Fall of

Ancient Heroes

• Mycenaean Civilization: The First

Greeks, 2000-1100 B.C.E.

Gold Mycenaean Death

Mask

10

Extent of Mycenaean Culture

11

The Rise and Fall of

Ancient Heroes

Mycenaean Civilization: The First Greeks,

2000-1100 B.C.E.

– Arose to commercial dominance in the Mediterranean after the fall of the Minoans, ca.

1450 B.C.E.

– Built large palaces that had considerable fortifications—unlike those of the Minoans—

suggested constant warfare

– Mycenaean pottery found across the Mediterranean, as had Minoan.

– Mycenaeans definitely were involved in raids and movements of people around 1200

B.C.E. that disrupted trade and brought on the Iron Age in Mesopotamian cultures.

– According to Greek legend, the Mycenaean invasion of Troy took place around 1250

B.C.E., creating the basis for Homer’s epic poem, The Illiad, which details the heroics of

the Trojan War.

– Greek legend attributes the ten-year absence of Mycenaean warriors during the war to

the fall of Mycenaean civilization.

– More likely caused by drought, famine, and invaders from the north known as Doric

12

Greeks

The Rise and Fall of

Ancient Heroes

From “Dark Ages” to Colonies

• The “Dark Ages,” the period from 1100 to 750 B.C.E., is called such

because of a lack of written record (scholars have translated Mycenaean

“Linear B,” unlike Minoan “Linear A”).

• Around 800 B.C.E., the blind poet Homer supposedly recorded some of the

oral traditions that had passed down through the Dark Ages.

• Renewed trade in olive oil, wine, and other goods seemed to help bring an

end to the Greek isolation of the Dark Ages.

• Greeks colonize places around the Mediterranean rim to escape famine and

political turmoil on the Greek peninsula, and later may have done so to

escape overcrowding.

13

The Greek Colonies in About 500 B.C.E.

14

The Rise and Fall of

Ancient Heroes

From “Dark Ages” to Colonies

• Values of the “Heroic Society”—one that values individual honor,

reputation, and prowess—from Mycenaean culture were preserved through

Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey.

• Arête – the highest value in Homeric literature, meaning manliness,

courage, and excellence. Competitive contests were the best proving

ground for this trait, with it be warfare or athletic events. The Greeks

thought this competitive quality separated them from the barbaroi.

• Kouros and Kore: Male and female sculpted figures that increasingly

became realistic and glorified individual human perfection.

15

Emerging from the Dark:

Heroic Beliefs and Values

Kouros and Kore

figures, both ca. 530

B.C.E.

How do these compare

to similar Egyptian

figures?

16

Emerging from the Dark:

Heroic Beliefs and Values

The Family of the Gods

– Greek historian Herodotus (482 – 425 B.C.E.) claims that poets Homer

(ca. 800 B.C.E.) and Hesiod (ca. 750 B.C.E.) had enormous influence

on the future development of Greek religion.

– Hesiod’s Works and Days describes daily life emerging from the Greek

Dark Ages; his Theogony provides stories of the origins of the Greek

gods, as well as mankind.

– Primary Gods: Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Apollo, and Demeter, who lived

on Mount Olympus and behaved as poorly as regular humans: they

were jealous, committed adultery, stole, and deceived.

– Religious rituals were not somber affairs, but had the air of celebration.

– Religious institutions did not become the center of Greek society, as

they had in Sumer, Egypt, etc.

17

Emerging from the Dark:

Heroic Beliefs and Values

The Family of the Gods

– Oracles were the religious class in ancient Greece, with the Delphic oracle of

Apollo being foremost; they went into trances possibly brought upon by ethane

gas that would allow visions that often had very ambiguous interpretations.

– King Croesus of Lydia asked the Delphic oracle around 546 B.C.E. about

Persian King Cyrus, and was told that a might empire would fall if he went to

war with the Persians, not realizing the oracle had meant his own.

– Later Greeks added Dionysus, the god of wine and fertility, to the list of

Homer’s Olympians, acknowledging the role of irrationality in human life.

– Hubris: While their gods had human qualities, Greeks warned humans of being

so arrogant as to think themselves god-like. Those who acted with this

quality—called hubris—were setting themselves up for a big downfall, a theme

that emerges frequently in Greek drama.

18

Emerging from the Dark:

Heroic Beliefs and Values

Studying the Material World

– Love of rational search for wisdom: philosophy

– Greek faith in human reason to figure out the natural world

– Thales (ca. 624 – 548 B.C.E.): Studied Mesopotamian and

Egyptian astronomy and predicted and eclipse; he though

everything was fundamentally derived from water.

– Democritus (ca. 460 – 370 B.C.E.): Came up with the idea

of infinite universe composed of tiny particles he called

atoms; he was seen as wrong until early twentieth-century

physicists proved him at least generally correct.

19

Emerging from the Dark:

Heroic Beliefs and Values

Studying the Material World

– Pythagoras (ca. 582 – 507 B.C.E.): Developed the Pythagorean

Theorem, demonstrating the relationship of angle widths within a

triangle; also was the first to propose that the earth and other heavenly

bodies were spherical and rotated on their axes.

– Practical Applications: Sixth-century engineer Eupalinus constructed a

3,000-foot tunnel through a mountain using geometric insights.

– Fears of “Impiety”: 432 B.C.E. Athenian law made it illegal to study

the material world at the expense of denying the gods; the law was

precipitated by philosopher Anaxagoras’s idea that the sun was a whitehot stone rather than a god.

20

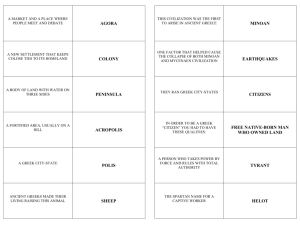

Life in the Greek Poleis

– Post Dark Ages: An emerging urban middle class of

merchants and artisans has no loyalties to aristocratic

landowners.

– Hoplite Armies: Intense trade makes metal weapons,

armor, and shields more affordable and in reach of

citizen-soldiers. City dwellers are no longer reliant on

aristocratic warriors for protection. They fight in

phalanx formations, with long spears jutting out from

tightly packed shields.

21

Life in the Greek Poleis

The Invention of Politics

– Tyrants: Between 650 and 550 B.C.E., many civil wars break out

as lower classes overthrow the aristocrats. New rulers called

tyrants emerged who ruled by force rather than hereditary or

constitutional right.

– Middle classes who controlled trade and fought as hoplites began

to take charge of politics in city-states (poleis).

– Poleis frequently had a fortified high ground called an acropolis

and a market/gathering place called an agora.

– City-states simultaneously began to develop varying

representational styles of government, from an early form of

democracy in Athens to an oligarchy (“rule of the few”) in

Corinth.

22

Life in the Greek Poleis

The Heart of the Polis

– Economy: Oliver Harvesting, Craftsmanship, and Trade

– Gymnasium: Physical prowess need to be cultivated as well

as intellectual – the hoplite or “citizen-soldier”

– Women’s Role: Upper-class women were expected to stay

indoors; public life was for men alone (Spartan women

were an exception)

– Greek society depended heavily on slave labor; slaves’

situation ranged from skilled work in which they could

retain some of their pay to harsh labor in mines

23

Life in the Greek Poleis

Fears and Attachments in Greek Emotional Life

– Bisexual Relations: Extreme separation of men and women

created some anxiety in gender relations and made

bisexuality common; Greeks often thought male-male love

could be the purest form of love

– Sappho of Lesbos: Sixth-century B.C.E. female poet from

the isle of Lesbos who wrote about her passion for women;

the word lesbian derives from her.

– Courtesans: Prostitutes were accepted and even registered

and taxed by many Greek city-states; they drank and

mingled with powerful men while “respectable” women

stayed home.

24

Life in the Greek Poleis

Athens: City of Democracy

– Oligarchy: By 700 B.C.E., Athenian aristocrats had developed a form of

government that put the day-to-day businesses in the hands of a administrators

called archons who were elected by an assembly of all male citizens called the

Ecclesia. The archons were overseen by a council of senior and powerful men

called the Areopagus, which eventually numbered 300, and wielded real power.

– Solon’s Economic Reforms: Around 600 B.C.E., Athenian society was

becoming weakened by food shortages and economic woes. An Athenian

aristocrat, Solon, was elected sole archon in 594. He instituted a wide array of

economic reforms: he canceled or limited debts, stopped exportation of

agricultural goods, and standardized weights and measures.

– Solon’s Political Reforms: Paved the way for men gaining wealth through trade

to access political power. He did not challenge the old aristocratic families, but

opened up ways for the newly wealthy to be elected to the highest offices. He

created a people’s court to check abuses by the archons. He weakened the

power of the Areopagus by creating a rival Council of the 400.

25

Life in the Greek Poleis

Athens: City of Democracy

– Tyranny: Solon’s reforms were ultimately unsuccessful since each group started asking

for more privileges, creating civil strife. Athens turned to tyranny—rule by force—to

deal with this chaos, bringing Peisistratus to power in 560 B.C.E. He ruled until 527

B.C.E. and was Athens last tyrant.

– Cleisthenes: The nobleman Cleisthenes who stood for popular interests proposed a

Constitution in 508 B.C.E. which refined Solon’s reforms and brought an unprecedented

level of direct democracy to the city. He redistricted the city so that the old alliances

based on clan and geography could no longer control city offices. He made Solon’s

Council of 400 to become the Council of 500, so that every clan affiliation could have

equal representation (50 per lot).

– Assessing Democracy: Athens was not a perfect democracy. Who was excluded from the

political system? Women, slaves, and foreigners called metics who lived and worked

within Athens and accounted for one-third of the city’s free population. The Council set

the agenda for the Ecclesia to vote on; the later was composed of all free male citizens

over thirty.

– Ostracism: Yearly mechanism by which someone perceived as a threat to Athenian

democracy could be banished for ten years if 6,000 people voted to do so. The names 26

were written on clay pottery shards.

27

Life in the Greek Poleis

Sparta: Model Military State

– Helots: Rather than negotiating and trading with surrounding peoples,

Sparta conquered and enslaved them, calling them helots.

– Strict Control through Might: Since the Spartans were outnumbered by

the helots, they maintained control by imposing strict military rule.

– Oligarchy: Authority was kept in the hands of the elders; Spartans had

no use for Athenian democracy

– Training of Boys: Sickly infants were left to die on the mountainside.

Seven-year-olds taken away from families to train until they were 20

and lived in the barracks eating plain food until they were 30.

– Spartan Women: Since men led an isolated soldierly existence, women

conducted the affairs of the household and had unusual independence.

28

29

Life in the Greek Poleis

Olympic Games

– First pan-Hellenic Games held in honor in 776 B.C.E.

– Greeks had different city-states, but they shared culture and religion:

called themselves collectively Hellenes.

– Started as a footrace, but events expanded to boxing, wrestling, chariot

racing, and a pentathlon: long-jump, javelin, discus, wrestling, and a

200-meter sprint.

– Spectators flocked to the games, which also included a celebration in

honor of Zeus and performance of dramas.

– The Games were a safe way for the city-states to compete.

– Women were not allowed to compete, but occasionally they held their

own games in honor of Hera, wife of Zeus.

30

Life in the Greek Poleis

Persian Wars (490 – 479 B.C.E.)

– In 499 B.C.E., a Greek city-state colony in Asia Minor, Miletus, rebelled

against the Persians, and Athens sent 20 ships in its defense: not enough to save

the city, but enough to anger the Persians.

– In 490 B.C.E., Persian King Darius sailed with a fleet across the Aegean and

landed near Athens to punish it for helping Miletus.

– Athenian soldiers met the Persians on the Plain of Marathon and were vastly

outnumbered. However, Athenian general Militiades managed to outflank the

Persians and made a running advance, which surprised the Persians. Texts

claim that 6,400 Persians died compared to 192 Athenians.

– The fast runner Philippides ran 150 miles in two days to request the help of the

Spartans. Legend has it that he ran 26 miles from Marathon to Athens to deliver

the news of victory and then died; this is probably just a myth.

– The small polis winning a victory over a huge empire gave Athens enormous

prestige in Greece.

31

Life in the Greek Poleis

Persian Wars (490 – 479 B.C.E.)

– Ten years after Marathon, Darius’s successor, Xerxes, plotted a full-scale invasion of the Greek

mainland, building a pontoon bridge across the Hellespont and brining 180,000 soldiers to

Greece. His men built a canal in northern Greece so that his troops could be supplied;

archaeological proof of the canal’s existence was recently uncovered.

– Several city-states in the north surrendered to the massive invading army.

– Athenians built up their fleet in attempt to control the Aegean and disrupt Persian supply routes,

and also secured the help of Sparta and its allies.

– Thermopylae: The Greeks forced the huge Persian forces to go through a narrow pass and

seemed to be winning until a Greek traitor led the Persians around the defended pass so that

they could attack the Greeks from behind. The Spartans stayed behind and fought to the death,

totally outnumbered.

– Athenians fled their polis in their ships, and were able to trap the Persian fleet in the narrow

Athenian harbor as the latter sacked and burned the city and attacked the ground forces as well.

– A year later, the Spartans led a coalition that destroyed the last remnants of the Persian Army.

– The historian Herodotus later wrote a 600-page detailed history of the conflict that in many

ways was the first modern work of history. His main theme was Greeks versus the

“barbarians”—the superiority of the Greeks was proven by their capacity to defeat a much

32

larger force.

The Persian Wars, 490-479 B.C.E.

33

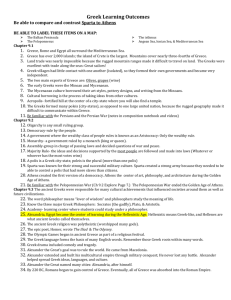

Greece Enters Its Classical Age

• Athens Builds an Empire, 477-431 B.C.E.

– Delian League: In 477 B.C.E., many maritime poleis decide to create a

defensive maritime league to protect trade. Each member contributed

money to maintain a great fleet that patrolled the area around the sacred

island of Delos, the supposed birthplace of Apollo.

– Athens gradually asserts a dominant role in the League, essentially

turning it into an empire with other members regarded as tribute or

vassals to Athens. In 454, Athens moved the fleet’s treasury from Delos

to Athens, which was very offensive to most Greeks.

– Pericles (495-429 B.C.E.) was in many ways the architect of the

Athenian golden age, was elected as strategoi in 443 B.C.E.

– Pericles’ Democracy: Took measures to ensure that even poor citizens

could participate in democratic institutions.

34

©2011, The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

35

Greece Enters Its Classical Age

Artistic

Athens

A modern rendering

of the Parthenon,

built 448-432 B.C.E.

after the raid on the

Delian treasury.

36

Greece Enters

Its Classical Age

Greek Architecture

– Temples constructed on the post

and lintel form.

– By 600 B.C.E., Greeks had two

different architectural “orders” for

designs of columns: Doric (the

oldest and simplest); the Ionic from

the eastern Mediterranean. Later

came the Corinthian, the most

elaborate that used an acanthus leaf

design (it was not used on the

Acropolis).

– Sculptures and reliefs on temples

featured idealized people, not real

human beings.

37

Greece Enters its Classical Age

Greek Theater: Exploring Complex Moral Problems

– Plays staged simply in outdoor theaters, with men playing both

men and woman, and everyone wearing a simple mask.

– Athenian playwright Aeschylus (ca. 525 – 456 B.C.E.) had

fought at the Battle of Marathon, and his earliest play, The

Persians, did not celebrate victory, but studied the Persian loss

and warned against Athenians becoming hubristic.

– Sophocles (ca. 496 – 406 B.C.E.) wrote a cycle called The

Theban Plays around the figure of Oedipus, who moves from

pride in being king of Thebes to humility and shame when he

comes to realize he had killed his father and is sleeping with his

mother. The play warned its viewers not to fall into

complacency.

38

Destruction, Disillusion, and a

Search for Meaning

The Peloponnesian War, 431-404 B.C.E.

– Long destructive war between Athens and Sparta triggered by Sparta’s response to

Athens’s aggressive behavior and its control of the Aegean Sea.

– Sparta forms the Peloponnesian League to challenge the power of the Athenian

Empire.

– Athenians’ fortified access to the sea made it impossible for the Spartans to starve

them out in a siege. Sparta had a land-based strategy, while Athens preferred to

attack from the sea. Sparta did burn crops, and plague struck Athens in 430-429

B.C.E., during which time Pericles died.

– Athenian morals declined during the war. The Athenians forced the islanders of

Melos, who wanted to remain neutral, to become allies. Those on Melos refused, so

Athenians slaughtered the men and enslaved the women and children.

– Athens overextended its fleet when intervening in Sicily, and Persians helped the

Peloponnesian League to strengthen its fleet, eventually leading to Athenian defeat

in 404 B.C.E.

– Historian Thucydides (460 – 400 B.C.E.) wrote an unusually unbiased account. 39

The Peloponnesian War, 431-404 B.C.E.

40

Destruction, Disillusion, and a

Search for Meaning

Philosophical Musings: Athens Contemplates Defeat

– Sophists: At the time of the Peloponnesian War (431-404

B.C.E.), this group of philosophers called for moral relativism,

arguing that “man is the measure of all things,” and thus the

individual needs to act on his or her own desires.

– Socrates (ca. 470 – 399 B.C.E.): Argued against the moral

relativism of the Sophists, using questioning to explore the

nature of “right action.” In the disillusioned time after the war,

Athenian authorities had little tolerance for those who focused

on human inadequacies and moral flaws, so they brought

Socrates up on charges of impiety and corrupting the young

(partly because the traitor Alcibiades had been his student) and

sentenced him to death.

41

Destruction, Disillusion, and a

Search for Meaning

Philosophical Musings: Athens Contemplates Defeat

– Plato (427 – 347 B.C.E.): This student of Socrates wrote many dialogues that

preserved his mentor’s ideas and put them alongside his own. He believed that

truth and justice only existed in the ideal world, and that people lived in the

imperfect realm of the senses, only a shadow of true reality. He founded the

Academy to teach young men about the ideal forms that existed outside of the

human world and could only be accessed through philosophical training. He

became disillusioned with the democracy that killed his teacher, and his The

Republic, proposed an ideal state run by “philosopher-kings.”

– Aristotle (384 B.CE. – 322 B.C.E.): He studied at Plato’s Academy but came to

disagree with his teacher’s ideas about “ideal forms,” arguing that ideas cannot

exist outside of their physical manifestations. Knowledge thus can only be

acquired by studying the physical world. He divided up the pursuit of

knowledge into several categories, many of which are still with us today, with

the main ones being ethics, natural history, and metaphysics. He saw any type

of government—monarchy, republic, or aristocracy—as potentially becoming

42

corrupt. A small polis with a strong middle-class would prevent extremes.

Destruction, Disillusion, and a

Search for Meaning

Tragedy and Comedy: Innovations in Greek Theater

– Euripides (485 – 406 B.C.E.): His plays grappled with

human anguish during he Peloponnesian War. The Trojan

Women dealt with the grief of captured women, and was an

implicit critique of the Athenian enslavement of the women

of Melos.

– Aristophanes (455 – 385 B.C.E.): Hi comedies used

ridiculous costumes and crude humor to create biting social

and political satire. In 411 B.C.E., he wrote Lysistrata, in

which women go on a sex strike until their men stop

fighting in the war.

43

Destruction, Disillusion, and a

Search for Meaning

Hippocrates and Medicine

Hippocrates (ca. 460 – 377 B.C.E.) was a key

figure in developing the western tradition of

medicine, replacing superstition in favor of

careful scientific observation and rejecting the

idea that bad spirits caused human ailments.

44

Destruction, Disillusion, and a

Search for Meaning

The Aftermath of War, 404-338 B.C.E.

– Athens agrees to break down its defensive walls, keep a fleet of only

twelve ships in its terms of surrender, and allow a Spartan garrison

within the city.

– Sparta proved a poor diplomatic manager of the alliance against

Athens, particularly when it gave over the Greek states in Asia Minor

to the Persians.

– Greek city-states continued to fight amongst each other—like Corinth

and Thebes—hastening the decline of the poleis.

– In 404 B.C.E., Sparta imposed a brutal thirty-man oligarchy over

Athens, which tried to stamp out the democratic forms.

– Increasing use of Greek mercenaries weakened loyalties to the citystate.

45