Public Interest Advocacy Centre - Australian Law Reform Commission

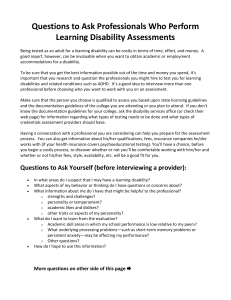

advertisement