Integrating Cultural Identity Stories from Preservice Teachers in a

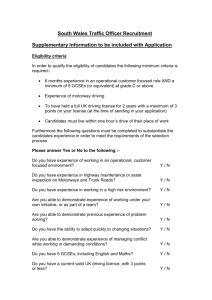

advertisement

1 Integrating Cultural Identity Stories Integrating Cultural Identity Stories from Preservice Teachers in a Bilingual Education Program: An Action Research Study Latino(a) students in a bilingual education teacher preparation program told their cultural stories that became mosaics of their journey in becoming culturally responsive teachers. They added bits and pieces of their cultural markers that created mosaic art of beauty. They began this process as they told their stories, reflected about their past, and named their cultural identities. Whatever meaning they made of their stories; however the mosaic of their journey appeared, they were becoming culturally responsive teachers that are so desperately needed in the classroom today. This paper describes the multicultural efficacy of teacher candidates as they reflected about their cultural identity. Their cultural identity stories provided valuable information about the beliefs and perspectives immigrant and children of immigrant teacher candidates told as they explored their own cultural identity. The culminating analysis of their stories described their cultural journeys through the following themes: Telling their Family Background and Immigration Stories, Establishing New Traditions, Negotiating their Education, and Giving Back to the Educational System. These cultural identities described the mosaic journey that the teacher candidates took. Cultural Mosaic: Sociocultural Theory, Reflective Practice, and Multicultural Efficacy The cultural mosaic metaphor reflects the integration of the various cultural elements and markers that describe the cultural identity of individuals. By describing the changed or blended 2 Integrating Cultural Identity Stories identities, individuals maintain their uniqueness while blending with their new identity (Eliam, 1999). Cultural mosaics are a complex system with localized structures; linking cultural tiles in what seems to be chaotic or random ways. They are metaphors that describe multidimensional structures within complex systems. The cultural mosaics simultaneously observe the global and local influences of individuals and groups while creating patterns of cultural identity (Chao & Moon, 2005). Researchers use the theoretical framework of sociocultural and sociopolitical theories (Giroux, 1992; Nieto, 2002) by focusing on the issues of teaching and learning in culturally diverse settings,. Many of the sociocultural theorists (e.g., Banks, 1988; Gay, 2003; LadsonBillings, 1995; Nieto & Bode, 2008; Sleeter, 2008; Trueba & Delgado-Gaitan, 1988) place people in their context in the world, and they view people from within their cultural, social, and political settings. Rather than living in isolation, people, in the light of this, are a part of a bigger social context that involves their social, political, and cultural worlds. Teacher candidates use the reflective practice as a part of their teaching and learning process. They begin making connections with their students. These connections lead to developing empathy for their students. They find ways to commit to the learning process. Kyles and Olafson (2008) found that preservice teachers needed multiple opportunities to reflect about their beliefs about teaching and their students. They found that they developed relationships with their students, which created the fragile teaching moment of transformative teaching. Donnell (2007) described a transformative process that teacher candidates made when they increased their personal teaching efficacy by focusing on the learning process with their students. The transformative pedagogy described by Vygotsky (1986) and Freire (1993), 3 Integrating Cultural Identity Stories explained that the teaching process had to be a mutual or reciprocal learning process between the teacher and the student. The relationships of the teacher/student dissolve into a mutual learning process. Method of Inquiry Teacher candidates in this qualitative study described their cultural background through cultural markers fé (faith), lengua (language), and sangre y tierra (blood and land) (Nieto 2002; Cummins, 1996). They claimed their identities as they were woven into their cultural identity. The research questions were: When teacher candidates focus on culture, identity, and language in their teacher preparation classes, will they increase their multicultural efficacy? When teacher candidates tell their cultural identity stories, will they increase their cultural connections and empathy for their students? The study was conducted in an urban education teacher preparation program in a South central city in the United Sates in 2009 and 2010. The participants were preparing to become bilingual education teachers. They were immigrant or children of immigrant parents from Mexico or Central or South America. The participants were identified as teacher candidates because they were in the last stages of the teacher preparation program. The teacher candidates participated in class lectures about culture, identity, and language that was based on the literature given above. Then, they followed the reflective writing process to create a cultural identity story. In this prewriting process, the participants identified cultural markers (Nieto, 2002; Cummings, 1996). Next, they wrote a Seven Minute Autobiography as described by Schneider (1994). They shared their stories with a partner in the class session. 4 Integrating Cultural Identity Stories Finally, the participants wrote a 5 page paper about their cultural identity based on these prewriting activities. The cultural identity paper was part of the data collection for the study. The participants described their family background, educational experiences, work history, and a statement about why they were in the teacher preparation program. They followed the writing process by including the cultural identity markers that were important to them. The participants also told stories about their travels to the U.S., traditions and celebrations, and different foods that they prepared and ate with their families. The analysis of the data was completed by a team of researchers. The researchers independently reviewed and analyzed the data by using Glaser’s (1965) comparative analysis method. By looking at the data first inductively and then deductively (Lewins & Silver, 2007), words and chunks of words of the stories were coded, while looking for themes, patterns, and/or connections. Themes that emerged from the data analysis: Culture Matters The participants found that culture did matter and that culture was important to them as they began developing as teachers. The cultural themes that emerged were: Telling Their Family Background and Immigration Stories, Establishing New Traditions while Maintaining the Old, Maintaining Spanish and English Languages. Negotiating their Education, and Giving Back to the Educational System. Telling their family background and immigration stories. 5 Integrating Cultural Identity Stories The teacher candidates told their stories about their family background. Some participants’ parents or grandparents migrated from Mexico, while many of the participants’ parents came from Central or South America. Their parents came to the U.S. to work as day laborers. JG stated: My roots go deep in Mexican soil. Not just because my parents were born in Mexico, but my family can be traced all the way back to my great-great-grandparents. My grandmother Juventina (and her side of the family) was born in Ocotlán, Jalisco and my grandfather Ramiro was born in Linares, Nuevo Leon. On my mom’s side of the family everyone comes from Bustamante, N.L. My mom’s ancestors were some of the first people settling in the small town. The teacher candidates recognized the sacrifices that their parents made for them when they came to the U.S. Establishing new traditions while maintaining the old. Because the teacher candidates lived in two worlds, they began to find ways to maintain and create new traditions. They described how important the Latino family network was. A family tradition was to celebrate all of the family birthdays, holidays, weddings, and funerals with the large, extended family. Elizabeth described Christmas at her house: Traditions can especially be seen during the holidays. This is the time of year when family members join each other in celebration of Christmas or New Years. Traditional foods are cooked and shared with all the guests. This includes the always must haves, the tamales, women gather around in the kitchen and make large amounts of mouthwatering tamales. Tamales made of pork, chicken, beans, cheese and peppers, sweet tamales made of fruit, hot or hotter or just plain ones. They usually make enough for that day and days to follow. Left over tamales are re-heated on the skillet and accompanied by a hot cup of coffee. Maintaining Spanish and English languages. The teacher candidates used both languages in their home and school cultures. They were proud that they maintained their Spanish language to communicate with their parents and 6 Integrating Cultural Identity Stories grandparents. They were raised in bilingual homes where their grandparents spoke Spanish, their parents spoke English and Spanish, and they spoke both languages. Joy said: Language was very important to my parents because they wanted their children to be able to speak both languages. They believed that it would help us become more successful with life in the United States. They also strongly believed that if they would not teach us Spanish, they were going to strip us of our culture and identity. I can now thank my parents for instilling my cultural background in me and showing me how a family can educate their children while showing them their origin. Negotiating their education. The teacher candidates and their parents learned how to negotiate the education system. . Some of the students participated in the bilingual education programs while others were in English as a Second Language programs. They experienced the high or low expectations of their teachers because of their ethnicity. They witnessed the additive or negative perspectives of their teachers. These teacher candidates successfully negotiated the education system by graduating from high school and then entering into the higher education system. Giving back to the educational system. The teacher candidates found that whether they had good or bad school experiences, they wanted to give back to their students by helping them become successful bilingual students. They wanted their students to have good experiences about being successful in school. They wanted to help their students negotiate through the educational system. They saw that the children in their classrooms looked like they did. They felt that they were mirroring their students. They had empathy for their students as they explored their cultural identities (Donnell, 2007). Ceci stated, The other day I was at work and I was given the opportunity to test the children in their oral language proficiency. The students that I tested had a confused look on their faces as 7 Integrating Cultural Identity Stories to why I was taking them out of their classroom. When I looked at their faces, I could picture myself the way I felt when I first entered the U.S. It is not just a language issue; it is also a whole new way of life, a new culture. Culture can be defined in many ways, but in order to comprehend the differences of culture in each of the students, one has to first identify how it affects them in the society they are in. The teacher candidates were experiencing what Félix-Ortiz et al (1994) described as high bicultural identities. They easily negotiated between the Latino and European American cultures. They were comfortable with using both English and Spanish. They could navigate easily between different cultural settings. By reflecting about their cultural identity, the teacher candidates discovered what was important to them. They could identify what they kept and what they let go of in their lives. They refused to abandon their language and culture to become a part of another culture. As the teacher candidates began to make connections with their students through language, traditions, and background, they began to see their students differently. They connected their cultural identity stories to the students’ cultural identity stories. They developed their confidence in the teaching because the students began to see them as teachers. Sometimes the students would say, “Are you a teacher? Wow!” and other times, they would say, “Miss, do you speak Spanish?” Donnell (2007) believed that this was because the students and teacher candidates began to see each other as “active agents” (p. 225). The teacher candidates had a transformative learning process as they made deep connections to their students. Ladson-Billings (1995) emphasized that students’ culture does matter in teaching. Learning cannot take place in the classroom when students experience a discontinuity or a mismatch between their home and school culture (Gay, 2000; Nieto, 2002). These teacher candidates found that culture did matter. They began the reflective process of looking back at their own culture. They named their culture, identified their experiences, and described their own 8 Integrating Cultural Identity Stories perspectives. By reflecting about their learning experiences, the teacher candidates discovered their passion for wanting to make a difference in the lives of their students. References: Banks, J. A. (1988). Multiethnic education: Theory and practice. Boston: Allyn & Bacon. Berta-Avila, M. I. (2004). Critical Xicana/Xicano educators: Is it enough to be a person of color? The High School Journal, 87(4), 66-79. Chao, G. T., & Moon, H. (2005). The cultural mosaic: A metatheory for understanding the complexity of culture. Journal of Applied Psychology. 90(6), 1128-1140. Cummins, J. (1996). Negotiating identities: Education for empowerment in a diverse society. Ontario, CA: California Association for Bilingual Education. Donnell, K. (2007). Getting to we: Developing a transformative urban teaching practice. Urban Education. 42(3), 223-249. Eliam, B. (1999). Toward the formation of a “cultural mosaic”: A case study. Social Pscyhology of Education. 2, 263-296. Félix-Ortiz, M., Newcomb, M. D., & Myers, H. (1994). A multidimensional measure of cultural identity for Latino and Latina adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 16(2), 99-115. Freire, P. (1993). Pedagogy of the oppressed (M.B. Ramos, Trans.) New York: Continuum. Gay, G. (2000). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. New York: Teachers College Press. Gay, G. (2003). Developing cultural critical consciousness and self-reflection in preservice teacher education. Theory into Practice, 42(3), 181-187. Giroux, H. A. (1992). Border crossings: Cultural workers and the politics of education. New York: Routledge. Glaser, B. G. (1965). The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Problems, 12(4), 436-445. Kyles, C. & Olafson, L. (2008). Uncovering preservice teachers' beliefs about diversity through reflective writing. Urban Education, 43(5), 500-518. Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Culturally relevant teaching. Theory into Practice, 34(3), 159-165. 9 Integrating Cultural Identity Stories Lewins, A., & Silver, C. (2007). Using software in qualitative research: A step-by-step guide. London: Sage Publications. Nieto, S. (2002). Language, culture, and teaching: Critical perspectives for a new century. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Nieto, S., & Bode, P. (2008). Affirming diversity: The sociopolitical context of multicultural education (5th ed.). Boston: Pearson. Schneider, P. (1994). The writer as an artist: A new approach to writing alone and with others. Los Angeles, CA: Lowell House. Sleeter, C. (2008). An invitation to support diverse students through teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 59(3), 212-219. Trueba, E., & Delgado-Gaitan, C. (1988). School and society: Learning content through culture. New York: Praeger. Vygotsky, L.S. (1986). Thought and language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.