Music Makers of the Dark Ages

advertisement

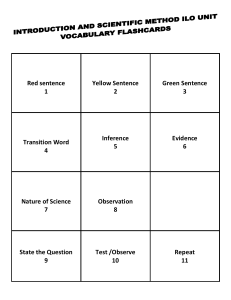

Musical Instruments of the Dark Ages Introduction Musical instruments of the medieval times can seem bizarre and alien in both formation and sound. Though outlandish, they still embraced a uniqueness and splendor of their own. These olden instruments paved the way to what we know as music today. It has taken centuries of experimentation and birth to reach our advanced point in music. Even as music has changed in sights and sounds dramatically from what it used to be, we can still marvel at the roots in an unfamiliar past. The Zink The zink is a late 14th century cousin of the cornet and trumpet. Unlike its later counterparts, it has six finger holes and a thumb hole instead of a valve system. The recorder and the zink share many resembling fingerings. The zink was an exceptional instrument of its time. It has the ability to play chromatically in multiple octaves. Control over the instrument gives it an enormous range of possibilities. Very little breath is actually used when playing this instrument. It is able to play as loud and as exuberant as a trumpet or as soft and gentle as a recorder. It is said that no other instrument has ever come so close to the sound of a human voice as the zink has. “It seems like the brilliance of a shaft of sunlight appearing in the shadow or in darkness, when one hears it among the voices in cathedrals or in chapels. (Mersenne, 1636)” The zink is made by hollowing out a piece of wood or ivory, straight or curved, and then buffed to form an octagonal shaped exterior throughout the instrument. It is then covered with leather to help protect the horn from the immense air pressure that it will be exposed to while being played. The mouthpiece is a very small acorn cup that is meant to be played on the side of the mouth because the lips are thinner and buzzing becomes easier. Mouthpiece of a zink. (Top) Various sizes and shapes of zinks. (Left) Various sizes and shapes of zinks. The zink is known as the most versatile wind instrument of the renaissance. It could be employed into multiple types of music. It could drive the vivacious, bouncy feel of a dance or mellow out to the legato and flowing feel of a ballad. The zink was an instrument for the true virtuoso. A great musician could take over the musical world of the renaissance wielding this instrument. During its prime, in the early Baroque period, it was locked in competition with the violin over instrumental dominance. However, the zink was unsuccessful in claiming its reign and would eventually be wiped out by the trumpet. The Crumhorn The crumhorn is a double reed instrument found in the woodwind family. It was first invented around the early 15th century and is the earliest instrument in the reed cap family. Unlike usual double reed woodwinds, such as the oboe or bassoon, the players lips don’t actually touch the reeds. Instead, one must blow through an open slot found at one end of a protective covering encasing the reeds so as the reeds vibrate to produce a sound. The fingering system found on the crumhorn is comparable to the fingerings of the lower register of the clarinet. Because of the reed cap structure, control over higher pitches can be very tricky. The normal range for the crumhorn is only an octave and one note. It has been suggested that some players might have played without the reed cap just to achieve higher notes. The crumhorn is a cylindrically shaped instrument. This means the airway is the same size throughout the entire horn without getting larger as would be found in conically shaped instruments. The construction of the instrument always consists of using wood for the body and reed cap and metal for aesthetics. Even the “mouth piece” that is to be blown on leading to the reed cap is formed of wood. The only exception to this all wood design falls on larger crumhorns that require a metal extension pipe to make playing more comfortable for the musician. The curve at the end of the instrument is purely for decoration. It serves no musical purpose. Various sizes of crumhorns. Crumhorn double reed and reed cap. (Left) Longer crumhorns have extension pipes or an elongated airway piece to accommodate for their larger size. (Right) The crumhorn was very crucial to the renaissance period. One could find these instruments at pretty much any medieval gathering that had music at the event. Its uses ranged from festivities at church and everywhere in between. Generally it has a sharp sound that allows it to stand out in an ensemble. In a more mild situation, it has the ability to produce a rich hum. Its utility and sound seems to reflect a combination of the modern day oboe and bassoon. The Harpsichord The harpsichord is one of two 16th century stringed keyboard instruments. Just as its successor, the piano, it uses keys to play a pitch. That and the exterior appearance are about as far as the similarities go. The sound of the harpsichord has a vast range of possibilities. It is dependent on the variation of the instrument, the region in which the individual instrument was built, and the time period in which it was built into. Earlier models tend to have a more sharp, crisp tone. These harpsichords were usually constructed of lighter wood. Later models give a richer and varied sound quality. These were built more solidly with heavier wood. Most harpsichords closely resemble a grand piano in size. Later in the 16th century, a smaller version, known as a spinet, was modified for domestic use. The harpsichord uses a very complex metal string system that is plucked to produce a sound. There is a small piece of material connected to the keys known as a plectrum. This is the plucking mechanism. When a key is pressed, the plectrum’s opposite end, away from the key, is raised and causes the string to be plucked. The plucking end of the plectrum is able to pivot using a “tongue” piece and avoid the string on its way back to its resting point. Due to the single pluck, it suffers from lack of control. There is no way to alter volume, note length, or quality of the tone. Detailed depiction of the plucking process. Inside look of a harpsichord. In its glory days, the harpsichord was played as a solo performer or as an accompaniment piece in larger groups. Many singers of the period also utilized the instrument for duet or small group purposes. The harpsichord would remain a vital component in ensembles until its importance plummeted by the birth of the piano. Even though the piano brought ruin to the instrument, the harpsichord was eventually resurrected and is still being used in traditional songs to this day. The Serpent The serpent is technically part of the brass instrument family. It is the late 16th century ancestor of today’s tubas, euphoniums, and baritones. Just as its new age successors, it has a conical bore, which results in a deep, mellow tone. It has been said that the serpent sounds like “a donkey with emotional problems" (David Raskin). Unlike its descendants, it has holes to change pitches instead of a piston or rotary valve system. When the serpent was invented, there were only a few ways to capably play a brass instrument. The three ways included; buzzing of the lips solely, buzzing of the lips and manipulating a slide, or buzzing of the lips and the covering and uncovering of holes. Because the serpent utilizes holes, it is capable of playing chromatically. Half-opening a finger hole allows the instrument to move in half step pitches to reach all notes within its three octave range. The serpent’s body is predominantly made from walnut wood. The body then has a covering of leather or varnished cloth to give the structure stability. A brass crook is extended out of the top of the instrument to position the mouthpiece at a playable location. The mouthpiece itself was formed from ivory, wood, or a plastic resin. There are versions of the serpent formed completely of brass, but they are not as popular as the original wooded design. Church (Left) and military (Right) serpent. The serpent is notable for its versatility. Even to this day it can be found in use in many venues. Around the time of its creation, the church and military serpent were the two most poplar variations of the instrument. In sacred music, its deep tones were used as a reinforcement for the bass in men’s voices. It had the ability to seamlessly mix with a choral group. About two hundred years after its invention, the serpent was integrated into military use. It would be played on horseback while the troops were moving from place to place or even during battle. Because of the weight and bulk, this instrument was also used as a defensive weapon if the player were to ever be attacked in combat. Resources A Guide to Medieval and Renaissance Instruments. Iowa State University, 1996. Web. 18 Nov. 2013 Paul, Schmidt. The Serpent Website. 1997. Web. 19 Nov. 2013 Lander, Nicholas. “Crumhorn Home page.” Recorder home Page. n.p., 1996. Web. 19 Nov. 2013 “The Harpsichord.” Hyper Physics. n.p., n.d. Web. 20 Nov. 2013 Resources “Instrumentos musicales del Renacimiento.” Listas. Web. 20 Nov. 2013 “Zink (Musik).” Wikipedia. Web. 20 Nov. 2013 “Harpsichord”. Wikipedia. Web. 20 Nov. 2013 “Harpsichord.” CSAIL. Web. 20 Nov. 2013 “Neapolitan Harpsichord.”Neapolitan-Harpsichord. Web. 21 Nov. 2013