The Tokugawa Shogunate - White Plains Public Schools

advertisement

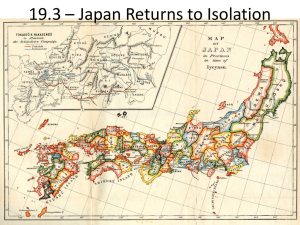

A Policy of Seclusion During the 1200s and most of the 1300s, the shogunates – the Kamakura (1185-1333) and the Ashikaga (1336-1573) – preserved order and kept Japan relatively unified However, decentralization became an increasingly serious problem during the late 1300s and 1400s Although, in theory, the Ashikaga Shogunate ruled the entirety of Japan, the country was breaking down into a patchwork of independent or semi-independent feudal states The rulers of these small states were nobles called daimyo Just as most medieval European nobles had been knights, most Japanese daimyo belonged to the warrior elite called samurai In 1467, the gradual breakdown of Japan suddenly turned into a condition of anarchy and collapse A civil conflict called the Onin War broke out that year and lasted till 1477 Disunity continued even after the conclusion of the war For the next hundred years, Japan experienced the “Era of Independent Lords” Daimyo fought daimyo constantly, and each treated his own territory as if it were an autonomous state Samurai troops, loyal to their daimyo masters, followed the code of Bushido, or “way of the warrior” Samurai who left their masters or whose masters were killed were known as ronins Ronins often served as mercenaries or became bandits The reunification of Japan was a process that lasted from 1560 to 1615 Three men brought about the unification First was the general Oda Nobunaga, one of the first military leaders to use gunpowder weapons in Japan He established his rule over eastern and central Japan In 1582, before he could complete full unification, he was assassinated The second unifier was Toyotomi Hideyoshi He brought almost all of the country back together again as a single nation However, he failed to create a political system that could survive after his death A man of humble origins, he could never assume the title of shogun even after he became ruler He died before his son reached adulthood Soon after, the five men he had appointed as regents for his son began to fight each other – and rebel against their boy ruler The victor and ultimate unifier of Japan was Tokugawa Ieyasu In 1600, Ieyasu defeated his fellow regents at the battle of Sekigahara In 1603, he appointed himself shogun From that moment forward, Ieyasu and his descendants would be the masters of Japan Of course, as all shoguns did, they technically ruled in the name of the emperor, who was cloistered and powerless in the ancient city of Kyoto (formerly Heian) The new government Ieyasu created was known as the Tokugawa Shogunate, and it lasted from 1603 to 1868 There were fifteen Tokugawa shoguns, and until near the end, their grasp on power and control over the nation was unassailable After so many years of war and chaos, stability, law, and order were the shogunate’s chief priorities Accordingly, the Tokugawa years are also known as the Great Peace Ieyasu centralized the country He established a new capital at the city of Edo, which is now the modern capital, Tokyo Peace came at the price of dictatorship, as well as increased social stratification Japan’s class system became more rigid than ever before, and until the mid-1700s, it was almost impossible for a person to move from one class or profession to another The power of the daimyo was reduced, and ordinary citizens were forbidden to own weapons The Tokugawa rulers also maintained a monopoly on gunpowder technology, and kept the number of guns in Japan as small as possible In Tokugawa Japan, women lived under increased restrictions, particularly in the samurai class, which was guided by Confucian teachings Wives had to obey their husbands or face death They had little authority over property In upper-class families, however, women expressed their literacy through creative pursuits and displayed social graces as a reflection of their husband’s rank and status In the lower classes, gender relations were more egalitarian However, as in previous eras, girl children were less valued, and sometimes either put to death or sold into prostitution The Tokugawa shoguns also sealed Japan off from the rest of the world as much as they could They were especially concerned to restrict the access of Europeans There had been Spanish, Portuguese, and Dutch in Japan during the 1500s: they traded and converted many Japanese to Christianity Distrusting the new religion, Japan’s rulers had struck out against Christianity several times Japan’s rulers persecuted and even crucified believers Hostility to Christianity and fear of foreign political and economic influence were behind the Tokugawa’s decision to close off the country in 1649 From then until the 1720s, foreign merchants were allowed entry only into one city, the port of Nagasaki A brief period of openness followed, and then Japan sealed itself off again until the 1850s Despite the oppressive nature of the Tokugawa regime, it had many accomplishments to its credit It restored and kept the peace The population grew rapidly Rice and grain production more than doubled between 1600 and 1720 Tokugawa Japan became highly urbanized (Edo was one of the world’s largest cities), and the shogunate built an elaborate network of roads and canals Economic growth was impressive: the Japanese became great producers of lacquerware, pottery, steel, and quality weapons During the 1600s and 1700s, one class that became increasingly wealthy and powerful was the merchant class (an exception to the general rule of social rigidity under the Tokugawa) In Japan, castle architecture partly imitated that of Europe As in Europe, Japanese castles were strategically built on hilltops, constructed of stone, and featured small windows, watchtowers, and massive walls Himeji Castle, one of the most famous of its kind in Japan, has decorated gables and roofs that once underscored the importance of its noble inhabitants In the field of drama, the formerly dominant, more restrained, and classically styled Noh play was now being eclipsed by kabuki Kabuki theater emphasized violence, physical action (acrobats and swordplay), and music It often depicted urban life in brothels and dance halls, and shogunate officials criticized it for its potentially corrupting effect on their subjects’ morals During the Tokugawa era, wood-block print came into its own as an artform In addition, whereas Chinese artists turned inward, Japanese art was more and more influenced by the outside world For example, Japanese potters fashioned their ceramics out of Korean techniques and designs Major reasons for this difference between Japan and China include the fact that Japanese urban areas were developing rapidly, along with their merchant and artisan classes, and Confucian values carried less weight there than in China The Tokugawa shoguns remained strong and dynamic through the mid-1700s Afterward, the Tokugawa still kept a tight grip over Japan, age and inflexibility began to take their toll on the system Gradual decentralization began to set it Tokugawa Japan also isolated itself from the rest of the world By the 1720s, the only country with which Japan maintained was Korea Informal ties were maintained with China, and the government allowed the Chinese and the Dutch to trade at the port of Nagasaki Over the course of the late 1700s and early 1800s, Tokugawa Japan partially modernized, both economically and socially Population growth was steady Japan, already a society of cities, experienced even more urban growth Kyoto and Osaka were major centers, and the capital, Edo, had a population of well over a million Agricultural techniques were rationalized or scientific techniques were applied allowing fewer people to grow more food The reform had the effect of boosting urbanization It also created the labor force needed to accelerate yet another trend: protoindustrialization Trade, commerce, and manufacturing became increasingly important A national infrastructure – more roads, canals, and ports – began to emerge The merchant class grew in number, wealth, and influence, becoming the middle class that any society needs to modernize Despite the country’s international isolation, some Japanese gained an awareness of scientific and technological knowledge from the West This partial modernization placed the shogun and the samurai class in a curious dilemma On one hand, such developments benefited Japan, making it a more prosperous and more advanced nation On the other hand, the spread of new foreign learning, the movement of people from countryside to city, and the increased social and economic clout of the merchant class all undermined the power of the 5 to 8 percent of the population that made up the traditional aristocracy Therefore, the regime allowed some modernization, but not as much as the country was capable of achieving In particular, members of the samurai class – whose military prowess was based on skill with traditional weapons such as swords – were anxious to preserve the state’s monopoly on the ownership of and ability to make gunpowder weaponry How long the Tokugawa leadership would have persisted in this approach is impossible to say But by the early 1850s, outside forces would change Japan forever IN 1853, American gunships appeared off the Japanese coast Their commander, Commodore Matthew Perry, bore a request from U.S. President Millard Fillmore, asking Japan to open its economy to foreign trade Although the Americans’ words were friendly, the threat of naval bombardment lay behind them After some debate, the shogun agreed to end his country’s decades-long isolation Over then next five years, other nations, principally the powers of Europe, compelled the Japanese to open up to them as well For a time, it appeared that Japan might fall victim to the same kind of Western economic pressure that was crippling China Painfully aware of what was happening to China, certain samurai leaders, particularly from the southern provinces of Satsuma and Choshu, urged the shogun to take a hard line This “Sat-Cho Alliance” gained a substantial following at the Edo court and pressed for the severance of all ties with the West Late in the year, antishogun forces asked the last shogun to resign and restore the emperor to full authority In January 1868, these forces, led by the SatCho, staged a military uprising and overthrew the last shogun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu The young emperor, Meiji, who had just ascended the throne in 1867, became the first emperor in nearly a thousand years to enjoy full imperial powers The Meiji Restoration of 1868 began Japan’s modern age Although the rebellion that had brought the emperor to power had been largely antiWestern in nature, even the most xenophobic members of the new Japanese government realized that, in order to avoid being dominated by the West, Japan would have to adopt Western learning, economics, and military methods One of the first things Meiji did, in 1871, was to abolish feudalism Japan began a process of modernization and industrialization that would profoundly change the course of its history and world history