Chapter 7-The Presidency - School of Public and International Affairs

advertisement

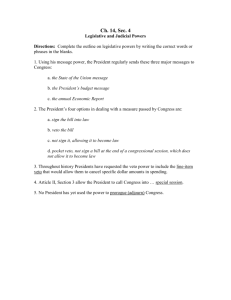

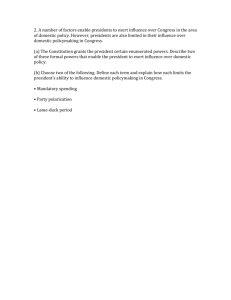

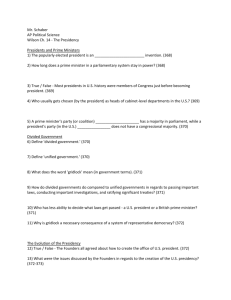

The Presidency as Paradox • The last eight presidents have left office under a cloud • Yet many aspire to the office and the president is perceived to be all-powerful • One explanation for this paradox is that the presidency is the one unitary institution in the federal government • “I am the decider” – George W. Bush The Personal President and Approval Ratings • One of the problems of the rise of the personal presidency is that presidents seem to become less popular over time Historical Presidency • The Framers intentionally designed the presidency to allow its occupant to rise to demands for quick and concerted action during times of crisis – Created a focal point for coordinating collective action – President best situated to propose a coordinated response. Framers and the Presidency • Framers rejected a plural executive. Thus, it would contain none of the internal checks provided by institutional design. • Instead, executive has resources to coordinate national responses, but not enough to usurp Congress • Two presidencies – Leadership goes to Pres during crisis – Does not suspend powers that belong to other institutions, and it dissipates as crisis recedes. The Constitutional Basis of the Presidency: Article II • Article II of the Constitution begins by asserting, “The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America” • Two important elements: – What is “the executive power” has remained a matter of dispute – Power is vested in “a” president, thus establishing the unitary nature of the office The President and the Constitution • “No person except a natural born Citizen, or a Citizen of the United States, at the time of the Adoption of this Constitution, shall be eligible to the Office of President; neither shall any Person be eligible to that Office who shall not have attained to the Age of thirty-five Years, and been fourteen Years a Resident within the United States.” Commander in Chief and Head of State • President is commander in chief of the nation’s armed forces • Founders had some difficulty in granting one individual control over the military • Checked this power by making it so ONLY CONGRESS can declare war. – The authority of commander in chief provides the president with broad license – Lincoln suspended write of habeas corpus that prevented the Union Army from detaining suspected spies and did not consult Congress Commander in Chief and Head of State • Idea that presidents have the military at tehir disposal (at least in the short run) remains unchallenged. • Congress’s check is a hollow one – War Powers Act of 1973 – Requires that the president inform Congress within 48 hours of committing troops to military action – Operation must end within 60 days unless Congress approves extension. The War Powers Act • The impact of this law has been limited • Presidents have continued to take military action without informing Congress – Reagan invaded Grenada in 1983 – George H.W. Bush deployed troops in Somalia in 1993. – In 1999 U.S. military participated in NATO action against former Yugoslavia. Head of State • The Framers provided broad authority to transact diplomatic affairs – Lesson learned from Articles of Confederation – Washington interpreted ‘receive ambassadors’ to mean that he alone had the authority to recognize new governments and receive its ministers – Truman recognized the state of Israel Head of State • The most important limitation on president in foreign affairs is that a two-thirds majority of the Senate is required to ratify treaties – Rejected WWI peace treaty – Wilson’s League of Nations – Not as limiting a check today due to exectuive agreements Executive Agreements • Unlike a treaty, an executive agreement cannot supersede U.S. law, and it remains “in force” as long as the parties find their interests well-served by it. – LBJ created a number of executive agreements giving foreign aid funds to countries that kept forces in Vietnam • These agreements are the mainstay of international relations • Congress can make laws that remove them and the courts can judge them unconstitutional. Executive Orders • Until the 20th century, presidents found themselves ill-equipped to intrude upon administrative practices • Congress exerciesed oversight of the bureaucracy, assigning its committees jurisdictions that matched those of the federal departments • Presidents stayed in the background and attempted to influence policy through political appointees to the bureaucracy or executive orders Executive Orders • Most arise from the authority and responsibilities explicitly delegated to the president by law. • A smaller class of executive orders is based not on some explicit congressional delegation but on the president's assertions of authority implicit in the Constitution’s mandate that the president: – “Take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.” “Take care” clause. Theodore Roosevelt first to subscribe to this expansive view of the office The President as a Legislator • The Constitution gives presidents only a modest role in the legislative arena. – May call Congress into special session. – Veto laws (Article I). – Must report “from time to time” to Congress with State of the Union address. • Yet modern presidents attempt to direct American policy by promoting a legislative agenda. • They must use their few constitutional tools as well as their ability to mobilize public support and their PARTY. The President as a Legislator • Until the twentieth century, presidents routinely delivered their “State of the Union” to Congress via courier, where it was read to an inattentive audience. • Today it is a “prime-time” opportunity for presidents to mold public opinion and steer the legislative agenda on Capitol Hill. • What are some of the things the president does during the State of the Union? – Stage and punctuate presentation with props and the introduction of “American heroes.” The President as a Legislator • Perhaps the president’s most formidable tool in dealing with Congress is the veto. – Constitution defines the veto precisely. • Used relatively rarely – most used by Gerald Ford. In the past fifty years, the average is fewer than ten vetoes a year. • The veto allows the president to block congressional action but does not allow the president to substitute his own policy preferences. The Nineteenth Century President • During the republic’s first century, presidents typically assumed a small role, thus in step with the Framers’ expectations. • They did not play a leadership role in domestic policy formulation. • Thus their accomplishments were limited to their responses to wars, rebellions, or other national crises. • A clerk and a commander…. The Era of Cabinet Government • Department secretaries played an important role during this period. • When a president had a question about a • policy, needed clarification on complaints, or needed advice on whether to sign or veto a bill he consulted his cabinet. • The relationship between a president and his cabinet at this time was one of reciprocity, not loyalty. • Cabinet members helped the president achieve his political goals and, through the cabinet appointment, he gave them opportunities to pursue theirs. The Modern Cabinet • The cabinet today has lost much of its luster as an attractive office; it only has limited political clout. • Control over policy and even of department personnel has gravitated to the White House. • Cabinet tenure today is not a stepping stone to a more powerful political position but rather a suitable conclusion to a career in public service. Parties and Elections • During the 19th century, politician attached as much importance to political party that controlled the executive as they did to the person himself. • Presidential elections were the focal point for national parties’ efforts • Winning the presidency usually meant that party took over Congress. The Nineteenth Century President • Were generally thought to be glorified clerks and Congress held the spotlight. • So what does the nineteenth-century presidency say about the modern one? – It reminds us that the Constitution does not thrust leadership on the president, but it hints at the potential the presidency has for a larger role. The Modern Presidency • As government expanded during the twentieth century, so did the workload of the president. • With additional responsibilities, the chief executive: – Gained discretion both in hiring personnel to administer these programs… – And in deciding what specific activities and regulations were necessary to achieve the mandated objectives The Modern Presidency • As the obligations of government grew, oversight of the executive began to tax Congress’s time and resources and its ability to do its work. • Congress found its own interests served by delegating to the White House a sizable share of administrative duties and the policy discretion that went with it. • Because the same party generally controlled these branches, it made it easier for Congress to transfer authority to the executive. • Often no practical alternative. Delegation • When members of Congress write public laws, they can decide to delegate a little or a lot of rulemaking authority to the president. • At times Congress delegates less from programmatic necessity than to gain political advantage. – When would they do this? – When they agree on the goals of a bill but disagree on its specifics. Thus they make the language vague and the executive branch has great leeway in how it implements the law. • Example: Congress delegated to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service discretion to establish rules for classifying species as “endangered” and “threatened.” Delegation • As attractive as delegation may be, it always has costs associated with it. – One must monitor agents’ performance to ensure that they are vigorously pursuing the tasks delegated. – “Fire Alarms, not Police Patrols.” • Agents may shift policy in an undesirable direction. – When that agent is the president, it is difficult to “fire” the agent. – Difficult to rein in a president as well, given the veto. Budgeting • The formulation and presentation of the annual budget to Congress is one of the president’s most important clerical tasks. – Offers presidents an opportunity to set the spending priorities of the federal government. • Authority comes from the delegation of duty from Congress -- 1921 Budgeting and Accounting Act. • Until the 1920s, agencies sent their budget requests directly to House Appropriations Budgeting • The president’s annual budget, submitted to Congress on the first Monday in February, takes months of work. – Assembling and negotiating requests from agencies. – Bringing them into conformity with White House policy goals. • Sometimes it sails through; other years replaced with “congressional” budget. • Provides Congress with valuable information. • Represents the president’s “opening bid” on how much will be spent for what and where the money will come from. Modern Presidents as Legislators • Today, Congress gives the president’s legislative proposals serious consideration. • Lawmakers expect the president to advise them about problems with current policy and administration and to recommend adjustments to improve performance. • Because of the president’s role administering the laws, a major role in the legislative process is ensured. – 90 percent of presidents’ initiatives are considered by some congressional committee or subcommittee. Working with Partisan Allies • In assembling support for their legislation, presidents begin with their party allies in Congress. • They cultivate this support by: – Advocating spending on programs and public works for a district or state. – Appointing a member’s congressional aide as an agency head. – Visiting a lawmaker’s district to generate support for the next reelection campaign. • These fellow partisans do what they can to support their leader. Obama and Legislative Initiative—House Votes Obama and Legislative Initiative—Senate Votes Unified versus Divided Control of Government • When presidents find their party in majority control of the House and Senate, they have excellent prospects for passing their legislative agenda. – Examples: New Deal and Great Society. • However, during divided government (when the president’s opposition party controls either or both legislative chambers), the president confronts majorities with different preferences Unified versus Divided Control of Government • During the past half century, unified party control has occurred less frequently than divided government. • How do presidents deal with this situation? – – – – Pull decisions into the White House. Carefully screen appointees to federal agencies. Utilize the veto. Go public (engage in intensive public relations to promote their policies to voters). • Republicans gained control of Congress in the 2002 midterm elections, restoring unified party control of government, which continued into the 109th Congress. Presidential Success on Congressional Votes Veto Bargaining • The veto offers presidents a clear, self-enforcing means of asserting their preferences. • The threat of a veto is a potent one as well. – Presidents can use the threat to manipulate Congress’s expectations about the likely result of alternative legislative packages, thereby inserting his policy preferences into legislation at an early stage of the process. • – Reagan: “Make my day.” Contemporary Bases of Presidential Power: Going Public • Going public is a tactic where presidents seek to force members of Congress to support their policies by appealing directly to and mobilizing the public – Bully pulpit • Presidents went public more and more often throughout the 20th century through speeches, radio, television, and now the internet Public Appearances by Presidents Contemporary Bases of Presidential Power: Personal President • As presidents went public more and more, the personal characteristics and skills of presidents became more important • For instance, Ronald Reagan’s success in divided government was attributed to his ability to communicate through television, skills he honed as an actor. – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vaTedoRjANU – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xfZg4UIuZe4 The Institutional Presidency • As an organization the presidency began modestly. – Washington used his secretary of state, Jefferson, to help him with correspondence. • By the early 1800s the number of staff working in and around the White House was less than a dozen. • When FDR became president there were about fifty staff members. (Maintenance, switchboard, and mailroom duties.) • In 1937 the President’s Committee on Administrative Management (Brownlow Committee) concluded that the “president needs help.” • Much like a CEO of a business, the president found himself in need of the tools to carry out the “business of the nation.” The Institutional Presidency Executive Office of the Presidency Typically, the agencies that make up the modern EOP work much more closely with the president and the White House staff than they do with each other. Perform classic staff functions: – Gather information. – Help maintain the organization itself. Office of Management and Budget • It is responsible for: 1. Creation of the annual federal budget. 2. Monitoring agency performance. 3. Compiling recommendations from the departments on enrolled bills (bills that have been passed in identical form in both chambers of Congress). 4. Administering central clearance. National Security Council • Its statutory responsibility appears modest: – To compile reports and advice from the State and Defense Departments and the Joint Chiefs of Staff and to keep the president well informed on international affairs. – Yet the national security advisor, who heads this presidential agency, has at times assumed a role in conducting foreign policy that is close to that traditionally associated with the secretary of state. A Unilateral President • What does this mean? • President – moves first, forces Congress and the Courts to react. Utilizes ambiguities in the Constitution. – Executive Orders – Executive Agreements – Vetoes – Signing Statements – Recess Appointments A Unilateral President Positives – Can be beneficial for Congress (ex: military base closings). President can move faster, work more efficiently due to the lower transaction costs. Say one needed to end the corrupt trade federation’s embargo of their home planet and was frustrated by bureaucratic delays. A unilateral executive could deal with such a situation quickly and efficiently. A Unilateral President? Negatives – Power can be abused and is very difficult to get back. It becomes difficult to get out of wars, to respond to executive orders or agreements or to reign in the usage of recess appointments or signing statements. In short, one day you’re giving the administration the ability to respond to the struggling economy and the next thing you know, they’re blowing up Alderaan