Auscultation for bowel sounds

advertisement

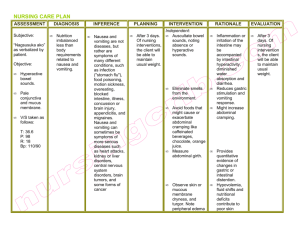

Abdominal Examination H.A.Soleimani MD Gastroenterologist General principles of exam Abdominal Examination The History and Physical in Perspective 70% of diagnoses can be made based on history alone. 90% of diagnoses can be made based on history and physical exam. Expensive tests often confirm what is found during the history and physical. Equipment for physical examination Required Optional Stethoscope Tongue blades Penlight Tape measure Sphygmomanometer Reflex hammer Safety pins Gloves Gauze pads Lubricant gel Nasal speculum Turning fork: 128 Hz,512Hz Pocket visual acuity card Oto-ophthalmoscope Important aspects of physical examination----physician Elegant appearance Decent manner Kind attitude Highly responsibility Good medical morals Important aspects of physical examination---physician Wash your hands, preferably while the patient is watching Washing with soap and water is an effective way to reduce the transmission of disease How to perform the physical examination? Exposing only the area that are being examined Offer a chaperone for both sexes. Explain what you're going to do Sequential Important aspects of physical examination The examiner should continue speaking to the patient Showing care to his disease and answer to patient’s questions It can not only release patient’s nerviness, but also help to establish the good physicianpatient relationship Gloves should be worn when.. Examining any individual with exudative lesions or weeping dermatitis When handling blood-soiled or body fluid-soiled sheets or clothing General principles of exam Good light Relaxed patient Full exposure of abdomen General principles of exam Have the patient empty their bladder before examination Have the patient lie in a comfortable, flat, supine position Have them keep their arms at their sides or folded on the chest General principles of exam Before the exam, ask the patient to identify painful areas so that you can examine those areas last During the exam pay attention to their facial expression to assess for sign of discomfort General principles of exam Use warm hand, warm stethoscope, and have short finger nails Approach the patient slowly and deliberately explaining what you will be doing General principles of exam Stand right side of the bed Exam with right hand Head just a little elevated Ask the patient to keep the mouth partially open and breathe gently General principles of exam If muscles remain tense, patient may be asked to rest feet on table with hips and knees flexed Other helpful points on examination Take a spare bed sheet and drape it over their lower body such that it just covers the upper edge of their underwear General principles of exam If the patient is ticklish or frightened Initially use the patients hand under yours as you palpate When patient calms then use your hands to palpate. Watch the patient’s face for discomfort. Think Anatomically Think Anatomically When looking, listening, feeling and percussing imagine what organs live in the area that you are examining. Right Upper Quadrant (RUQ) liver, gallbladder, duodenum, right kidney and hepatic flexure of colon Right Lower Quadrant (RLQ) Cecum, appendix (in case of female, right ovary & tube) Left Lower Quadrant (LLQ) Sigmoid colon (in case of female, left ovary & tube) Left Upper Quadrant (LUQ) Stomach, spleen, left kidney, pancreas (tail), splenic flexure of colon Epigastric Area Stomach, pancreas (head and body), aorta Landmarks of the abdominal wall, Costal margin, umbilicus, iliac crest, anterior superior iliac spine, symphysis pubis, pubic tubercle, inguinal ligament, rectus abdominis muscle, xiphoid process. Physical Examination of the Abdomen Inspection Auscultation Percussion Palpation Special Tests Inspection Abdominal examination Appearance of the abdomen Is Aortic pulsation? Is it flat or Scaphoid (Normally)? Distended? If enlarged, does this appear symmetric? With bulging or moving? Symmetrical in shape Scaphoid or flat in young patients of normal weight slightly full but not distended in older age group due to poor muscle tone or in subjects who are mildly overweight Appreciation of abdominal contours Standing at the foot of the table and looking up towards the patient's head. Lower yourself until the anterior abdominal wall and ask the patient to breathe normally while you are doing so. Appearance of the abdomen Global abdominal enlargement is usually caused by air, fluid, or fat. Appearance of the abdomen Localized enlargement probably distend GB space occupying lesion, hepatomegaly…. An aortic aneurysm Palpable mass Patient feeling of pulsation On rare occasions, a lump can be visible. An aortic aneurysm 1 in 10 men over 65 may have some enlargement of the abdominal aorta. About 1 in 100 will have a large aneurysm requiring surgery. Appearance of the abdomen (Skin) Abnormal venous patterns Abnormal discoloration Umbilicus is sunken Striae Stretch marks are a light silver hue. Pregnancy and obese individuals Cushing’s syndrome (more purple or pink). Appearance of the abdomen (Skin) Tattoos Scars can be drawn on schematic diagrams of the abdomen (a picture is worth a thousand words). Cullen’s sign Ecchymosis periumbilically. (intraperitoneal hemorrhage ruptured ectopic pregnancy, hemorrhagic pancreatitis..) Grey-Turner’s sign Ecchymosis of flanks. (retroperitoneal hemorrhage such as hemorrhagic pancreatitis) Upward flow direction indicates IVC obstruction Outward flow pattern from umbilicus in all directions ? Portal HTN Evaluate venous return states Place index finger side by side over a vein and press laterally, milking vein. Release one finger and time refill, repeat with other finger. Venous return is in direction of faster filling. Appearance of the abdomen Areas which become more pronounced when the patient valsalvas are often associated with ventral hernias Visible Pulsations More conspicuous in the thin than in the fat Greater in the old than in the young. Increased in thyrotoxicosis, hypertension, or aortic regurgitation) In those with an aortic aneurysm and tortuous aorta In those who have a mass joining the aorta to the anterior abdominal wall. Visible gastric Peristalsis Visible intestinal Peristalsis Gastric peristalsis is commonly seen in neonates with congenital hypertrophic pyloric stenosis Intestinal peristalsis in partial and chronic intestinal obstruction Colonic obstruction is usually not manifest as visible peristalsis Appearance of the abdomen Patient's movement Patients with kidney stones will frequently writhe on the examination table, unable to find a comfortable position Appearance of the abdomen Patient's movement Patients with peritonitis prefer to lie very still as any motion causes further peritoneal irritation and pain. Auscultation Abdominal examination Auscultation Bowel sounds Vascular sounds (bruits) Friction Rubs Auscultation for bowel sounds It is performed before percussion or palpation Auscultation for bowel sounds Normal sounds are due to peristaltic activity. Peristalsis: A pregressice wavelike movement that occurs involuntarily in hollow tubes of the body. Auscultation for bowel sounds Compared to the cardiac and pulmonary exams, auscultation of the abdomen has a relatively minor role. Auscultation for bowel sounds Bowel sounds lend supporting information to other findings but are not pathognomonic for any particular process. Auscultation 1.Diaphragm of stethoscope used 2.Skin depressed to approximately 1 cm Auscultation 3.Listening in one spot is usually sufficient 4.Listening for 15-20 or 30-60 seconds 5.Bowel sounds cannot be said to be absent unless they are not heard after listening for 3-5 minutes. Three things about bowel sound Are bowel sounds present? If present, are they frequent or sparse (i.e.quantity)? What is the nature of the sounds (i.e.quality)? Bowel sound decrease Inflammatory processes of the serosa After abdominal surgery In response to narcotic analgesics or anesthesia. Auscultation for bowel sounds Inflammation of the intestinal mucosa will cause hyperactive bowel sounds. Auscultation for bowel sounds Processes which lead to intestinal obstruction initially cause frequent bowel sounds, referred to as "rushes." Auscultation for bowel sounds Processes which lead to intestinal obstruction initially cause frequent bowel sounds, referred to as "rushes." Auscultation for bowel sounds “Rushes" means as the intestines trying to force their contents through a tight opening. Auscultation for bowel sounds “Rushes" is followed by decreased sound, called "tinkles," and then silence. Auscultation for bowel sounds After silence the appearance of bowel sounds marks the return of intestinal sounds activity, an important phase of the patient's recovery. Splash Sign Splashing sound indicative of air or fluid in body cavity with shaking individual: normal in s stomach. Auscultation for bowel sounds Bowel sounds, then, must be interpreted within the context of the particular clinical situation. Bruits Bruits confined to systole do not necessarily indicate disease. Auscultation for vascular sounds (bruits) Aortic (midline between umbilicus and xiphoid Renal (two inches superior to and two inches lateral to umbilicus) Common iliac (midway between umbilicus and midpoint of inguinal ligament) Auscultation for vascular sounds (bruits) Presence of a bruit on the renal artery would lend supporting evidence for the existence of renal artery stenosis. Auscultation for vascular sounds (bruits) When listening for bruits, you will need to press down quite firmly as the renal arteries are retroperitoneal structures. Venous Hum (rare) Epigastric/umbilical area. Soft humming noises in systolic/diastolic component. Indicates collateral between portal and venous systems as in hepatic cirrhosis. Rubs –Rubs-Rubs Liver Spleen Cardiac Pulmonary Friction rubs (rare) Right and left upper quandrants Grating sound with respiratory movement Indicates inflammation of the capsule of the liver or spleen (infection or infarction). Percussion Abdominal examination Percussion Technique Liver Spleen Percussion (technique) DIP joint of third finger (pleximeter) pressed firmly on the abdomen remainder of hand not touching the abdomen Percussion (technique) Striking hand should move only at the wrist, with only little more than force of gravity Percussion (technique) Middle finger of striking hand (plexor) should knock the pleximeter firmly, with a strong note There are two basic sounds with Percussion Tympanitic (drum-like) sounds produced by percussing over air filled structures. There are two basic sounds with Percussion Dull sounds that occur when a solid structure (e.g. liver) or fluid (e.g. ascites) lies beneath the region being examined. Examination of Liver (Percussion) Midclavicular line is noted Second intercostal space is noted The two solid organs are percussable in the normal patient Liver: will be entirely covered by the ribs. Occasionally, an edge may protrude 1-2 centimeter below the costal margin. Spleen: The spleen is smaller and is entirely protected by the ribs. To determine the size of the liver Measure the liver span by percussing hepatic dullness from above (lung) and below (bowel). A normal liver span is 6 to 12 cm in the midclavicular line. To determine the size of the liver Start just below the right breast in a line with the middle of the clavicle. Percussion in this area should produce a relatively resonant note. To determine the size of the liver Move your hand down a few centimeters than you will be over the liver, which will produce a duller sounding tone. To determine the size of the liver Continue downward until the sound changes once again. At this point, you will have reached the inferior margin of the liver. Examination of Liver (Percussion) Upper margin is noted by first dull percussion note Lower margin is noted by first tympanitic note To determine the size of the liver The resonant tone produced by percussion over the anterior chest wall will be somewhat less drum like then that generated over the intestines. While they are both caused by tapping over air filled structures, the ribs and pectoralis muscle tend to dampen the sound. Examination of Spleen (Percussion) Percussion at Castell’s Spot Castell’s Spot identified Left anterior axillary line identified Left lower costal margin identified Percussion at Castell’s Spot while patient inhales and exhales deeply Dull tone indicates possible splenomegaly Spleen percussion Enlarged spleen produce a dull tone, in the left upper quadrant percussion but should then be verified by palpation. Palpation Abdominal examination Abdominal Palpation Technique Light Deep Liver edge Spleen tip Kidneys Aorta Masses Abdominal palpation To palpate four quadrants superficially from LLQ counterclockwise Light Palpation Light Palpation First warm your hands by rubbing them together before placing them on the patient. Abdominal wall depressed approximately 1 cm Abdominal palpation Use pads of three fingers of one hand and a light, gentle, dipping maneuver to examine abdomen Palpation (light) Any areas of pain or tenderness are reserved for evaluation at the end of the exam Light Palpation Mostly looking for areas of tenderness Tenderness is a physical exam finding a reflex occurs (muscle splinting, wide eyes, moaning, teeth gritting). Palpation Light palpation assesses Muscle tone Cutaneous hypersensitivity (suggests peritoneal irritation) Palpation Light palpation assesses Presence of superficial (intramural) masses is more prominent if patient raises their head ,Intra-abdominal mass is less prominent if patient raises their head Deep Palpation Palpation (deep) Entire palm Either one- or two handed technique is acceptable Deep Palpation Use palmar surface of fingers of one hand (greatest number of fingers) and a deep, firm, gentle maneuver to examine abdomen Palpation Palpate deeply with finger pads (do not “dig in” with finger tips) Deep Palpation Palpate tender areas last Try to identify abdominal masses or areas of deep tenderness Two handed technique When deep palpation is difficult, examiner may want to use left hand placed over right hand to help exert pressure Palpation (deep) Push as deeply as patient will allow without significant discomfort Normal structure that may be palpable Sigmoid colon Liver Kidney Abdominal aorta Iliac artery Distended bladder Gravid and nongravid uterus Xyphoid process spleen Abdominal mass Intra abdominal masses or enlargements of the liver, gallbladder or spleen Abdominal wall mass Intra abdominal masses or enlargements of the liver, gallbladder or spleen They will shift down with inspiration and back with expiration. (not true of masses within the abdominal wall or retroperitoneal structures). Aabdominal wall mass It will become more evident and palpable when patient flexes neck as this contracts rectus muscles. Paraumbilical node Abdominal pain and Tenderness Type of abdominal pain Visceral pain Somatic pain Visceral pain This is pain that arises from an organic lesion or functional disturbance within an abdominal viscus (dull, poorly localized, and difficult for the patient to characterize). Somatic pain Painful lesion of the skin Sharp, bright, and well localized Indicates involvement of parietal peritoneum or the abdominal wall itself Tenderness If there is tenderness determine the point of maximum tenderness and its distribution Abdominal muscle spasm Voluntary guarding Tensing abdominal muscles due to patient anxiety, ticklishness, or toprevent palpation to a painful area Involuntary guarding Muscular spasm or rigidity due to peritoneal inflammation May be localized (early appendicitis )or diffuse (perforated bowel) Board-like rigidity If abdominal wall is palpated as obviously tense, even as rigid as a board, board-like rigidity is so called. Is caused by the spasm of abdominal muscle due to peritoneal irritation. Differential diagnosis of abdominal pain Spine pain Abdominal wall pain( differentiated by having the patient tense his abdominal muscles, by forcefully elevating his head while keeping his shoulders flat on the table) Liver palpation Liver palpation (Standard Method) Start in the RUQ,10 centimeters below the rib margin in the midclavicular line Place left hand posteriorly parallel to and supporting 11th & 12th ribs on right. Standard Method Liver palpation Ask the patient to take a deep breath. You may feel the edge of the liver press against your fingers. Liver palpation (Standard Method) Palpating hand is held steady while patient inhales Liver palpation (Standard Method) Palpating hand is lifted and moved while the patient breathes out Liver palpation Another method of palpating the liver uses the radial border of the index finger. In this method the anterior hand is placed flat on the anterior abdominal wall with fingers parallel to the costal margin Alternate Method Liver palpation Is useful when the patient is obese or when the examiner is small compared to the patient. Alternate Method Liver palpation Stand by the patient's chest. "Hook" your fingers just below the costal margin and press firmly. Hepatomegaly More than 1cm below the costal margin An exception is a congenitally large right lobe of the liver Severe, chronic emphysema Pulsation transmitted from aorta Tricuspid valve insufficiency Hepatojugular reflux sign If you press the liver, you will find the dilated jugular vein becomes more bulged or distended, as from the enlargement of liver passive congestion resulted from right failure. Ballotable sign Spleen palpation Spleen palpation Seldom palpable in normal adults. Causes include COPD, and deep inspiratory descent of the diaphragm. Spleen palpation Support lower left rib cage with left hand while patient is supine and lift anteriorly on the rib cage. Spleen palpation Palpate upwards toward spleen with finger tips of right hand, starting below left costal margin. Have the patient take a deep breath. Examination of Spleen (Palpation) Deep technique used Starting point is RLQ, proceeding to LUQ Kidney palpation Kidney palpation Place left hand posteriorly just below the right 12th rib. Lift upwards. Palpate deeply with right hand on anterior abdominal wall. Examination of Kidney Patient take a deep breath. Feel lower pole of kidney and try to capture it between your hands. Examination of Kidney Right kidney may be felt to slip between hands during exhalation Palpation of the Aorta Examination of Aorta Flat palm placed over the the epigastrium to locate pulse Examination of Aorta Press down deeply in the midline above the umbilicus. The aortic pulsation is easily felt on most individuals. Examination of Aorta Hands then oriented vertically on either side of midline with distal fingers at level of pulsation; equal pressure applied until pulsation is palpated A well defined, pulsatile mass, greater than cm across, suggests an aortic aneurysm. Examination of Aorta Lateral width of pulsation is determined by space between index fingers Special exam Abdominal examination Special exam Murphy’s Sign McBurney’s Point Rovsing’s Sign Psoas Sign Obturator Sign Re bound Tenderness Costovertebral tenderness Shifting Dullness Fluid wave Murphy’s Sign (acute cholecystitis) Examiner’s hand is at middle inferior border of liver. Patient is asked to take deep inspiration. If positive patient will experience pain and will stop short of full inspiration Hepatitis, subdiaphragmatic abscess Cholecystitis McBurney’s Point Localized tenderness Just below midpoint of line between right anterior iliac crest and umbilicus. Heel strike, riding over bumps in road while driving, coughing, will produce pain. McBurney’s Point (Common Causes) Appendicitis Incarcerated or strangulated hernia Ovarian torsion (twisted Fallopian tube) Pelvic inflammatory disease Abdominal abscess Hepatitis Diverticular disease Meckel''s diverticulum Rovsing’s Sign Patient will experience right lower quadrant pain (in region of McBurney’s Point) when left lower quadrant is palpated. Non-Classical Appendicitis Iliopsoas Sign Obturator Sign Iliopsoas Sign Patient can lay on side and extend leg at the hip or have patient lay on back and try to flex hip against the resistance of examiner’s hand on thigh. If patient has an inflamed retrocecal appendix, this will produce pain. Iliopsoas Sign Anatomic basis for the psoas sign: inflamed appendix is in a retroperitoneal location in contact with the psoas muscle, which is stretched by this maneuver. Obturator Sign Internally rotate right leg at the hip with the knee at 90 degrees of flexion. Will produce pain if Obturator Sign Anatomic basis for the obturator sign: inflamed appendix in the pelvis is in contact with the obturator internus muscle, which is stretched by this maneuver. Rebound Tenderness (For peritoneal irritation) Warn the patient what you are about to do. Press deeply on the abdomen with your hand. After a moment, quickly release pressure. If it hurts more when you release, the patient has rebound tenderness. [4] Cost vertebral Tenderness (Often with renal disease) Use the heel of your closed fist to strike the patient firmly over the costovertebral angles. Compare the left and right sides. Warn the patient Patient sit up on the exam table Shifting Dullness (For peritoneal fluid) Percuss from anterior abdomen laterally to outline areas of dullness noted Examination for Shifting Dullness Patient rolled slightly toward the examined side; movement of the dull point medially is described as “shifting dullness” and suggests ascites Shifting Dullness Fluid wave