Plagiarism Prevention Strategies - UW Blogs Network

advertisement

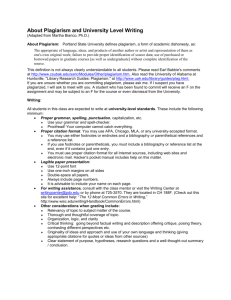

TA/RA Conference Responding to Longer Student Essays Plagiarism Prevention Strategies Plagiarism has gotten a lot of press lately as a growing problem on university campuses. And while you won't be able to prevent every student in your classes from plagiarizing, there are some strategies you can employ to help prevent it. First, though, it's important to think about why students plagiarize. Here are a few common reasons we see University of Washington students turn in plagiarized work: They don't understand what plagiarism is. Students might not fully understand what counts as plagiarism and what they need to do to avoid it. Cultural differences regarding intellectual property as well as disciplinary differences in citation practices mean that well-meaning students don't always realize that what they're turning in might be considered plagiarism. They have poor research skills. The internet has changed the way students research. Instead of paraphrasing texts on note cards, they now cut and paste from web pages. It can be easy for students to lose track of what came from where when juggling a mass of different web "clippings" and so they fail to properly reference their sources. They get desperate. A student who doesn't understand an assignment or doesn't feel prepared to complete one may find himself staring at a blank page at 3:00 am the morning it's due. It is easy to imagine that student turning to the internet in desperation to flush out the last two pages with a few borrowed paragraphs. Grades have become the priority. Whether as a requirement for acceptance into a competitive major or as a ticket to a good job, grades are valuable commodities for students. And that real pressure to get good grades can lead some students to make bad choices. The following are some strategies instructors have found effective in discouraging plagiarism: 1. Make the consequences of plagiarism clear to students. Put a plagiarism policy in your syllabus. Here's one example from a literature class: "Plagiarism is the representation of another's words or ideas as your own. This can range from paraphrasing an author's idea without giving proper credit to buying a paper to turn in as your own. I expect every student to follow MLA citation guidelines whenever borrowing from another’s work or ideas. If you are uncertain of MLA citation style, please come see me. I take plagiarism, and all other forms of academic dishonesty, very seriously. I will investigate any suspicious contributions thoroughly and follow through with discipline according to school policy (which can range from academic probation to expulsion). If your quarter is getting hectic and you don't see how you can finish an assignment without plagiarizing, come talk to me. I would rather extend a deadline than have to report you." In the end, though, remember that most of your students have no intention of plagiarizing, so be careful of painting them all as potential plagiarists. Page 1 of 4 The Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) (206) 543-6588 | 100 Gerberding Hall | http://www.washington.edu/teaching. TA/RA Conference Responding to Longer Student Essays 2. Teach students how not to plagiarize. Students often do not understand scholarly conventions for citation. Take class time to ensure that students understand exactly what your discipline expects of them in terms of the use they make of other people’s work. There are a number of good web resources for students now available. Some examples: Psychology Writing Center’s handouts: http://www.psych.uw.edu/psych.php#p=339 Citation Style Guides for Internet and Electronic Sources http://guides.library.ualberta.ca/citation_internet Help your students learn to distinguish between acceptable paraphrasing and plagiarism. See the following examples from ASU’s Department of Sociology: http://www.aug.edu/sociology/plagiarism.html 3. Assign drafts or other low-stakes preliminary writing assignments. One way to support students throughout the writing process is to get people writing early, both so they can learn early what they need to know in order to do the work themselves, and so that you can see any problems they are having well before it’s too late to do something about them. If you can, break big assignments into smaller, manageable tasks. For example, you may require students to turn in a paragraph-long summary of their paper one week, and a short draft the next week. Preliminary assignments also give you a chance to get to know your students' writing styles a bit better so that you can have an easier time recognizing suspicious variations in their later papers. The "Developing a Thesis" handout can be one way of incorporating preliminary writing into an assignment. See also this “Focus Checklist": http://writingcenter.unc.edu/faculty-resources/classroom-handouts/thesis-analysis/ 4. Urge students to use Writing Center support. Conversations with writing tutors can help them solve research and writing problems that might otherwise send them to internet paper mills. UW writing centers: http://guides.lib.washington.edu/citations 5. Design assignments that are hard to plagiarize. o The best plagiarism prevention is a well-designed assignment. For example, keep topics specific and focused – and find ways to modify them slightly each quarter. Assign specific texts or case studies that are not widely discussed on the internet or other classes at the UW. o Also see Peter Elbow on assignment design: www.ntlf.com/html/lib/bib/writing.htm If you do find yourself dealing with a plagiarized paper, talk with your supervising instructor or administrator about the appropriate steps to take. See also the Faculty Resource on Grading: http://depts.washington.edu/grading/conduct/index.html Page 2 of 4 The Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) (206) 543-6588 | 100 Gerberding Hall | http://www.washington.edu/teaching. TA/RA Conference Responding to Longer Student Essays Making the most of your time and energy: Communicate your expectations clearly! Supply grading criteria to students Why use explicit grading criteria? It demystifies what is for many students is a very mysterious process. It enables instructors to read and respond to papers more easily and effectively. It promotes consistency of grading across sections taught by different instructors (but only if they discuss their interpretation/application of these criteria to actual student papers). Suggestions for developing criteria (Your instructor or fellow TAs may have a set of grading criteria they have found effective in the past. If they do not, or if it requires adaptation for this assignment, here are some tips on how to develop explicit grading criteria): Review examples of other instructors’ grading criteria. Note what you like and don’t like about these criteria. Find one that is laid out in a way you like. Limit yourself to the three or four most important ingredients of a student paper that successfully completes the assignment you are grading. For example, many instructors value “organization” or “effective use of evidence from course readings.” If you’re stuck, you might consider: what three or four things do student responses to this assignment often lack? Be specific about what those ingredients are. What do you mean by “organization?” How would you describe a paper that meets this criterion? E.g., “Introduction to the essay clearly presents the point(s) to be made in the discussion.” Or “Sequencing of ideas within paragraphs and transitions between paragraphs make the writer’s points easy to follow.” Decide how you will weight your criteria. Given the goals of this assignment, is “organization” more important than “grammar and mechanics” or “correct use of course concepts and terms”? How to use criteria with your students: Staple a criteria sheet to each student’s paper and indicate which criteria they have met and which they have not met. You can make comments on this form or refer them to certain pages in the assignment where you’ve written additional comments. If possible, share your criteria with your students before they write, taking time to explain what you mean by each criterion (and, if possible, illustrating this discussion with excerpts from models.) Incorporate criteria into daily class work. For example, you might have students evaluate a sample paper – or each other's papers – using the criteria. You can also design lesson plans around a criterion (e.g. a fifteen minute activity on organization). Page 3 of 4 The Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) (206) 543-6588 | 100 Gerberding Hall | http://www.washington.edu/teaching. TA/RA Conference Responding to Longer Student Essays Further Resources For Instructors: CIDR Bulletins available on the UW CTL website: http://www.washington.edu/teaching/teaching-resources/archiveof-cidr-bulletins-on-teaching-and-learning/ See specifically: Helping Student Writers Succeed (2000) Helping Students Read Well (2001) The University of North Carolina’s Writing Center has many practical tools available on their website. http://www.unc.edu/depts/wcweb/ The Writing Across the Curriculum Clearinghouse at Colorado State University has many resources, including an annotated bibliography. http://wac.colostate.edu/index.cfm Current writing requirements for UW undergraduates: Students in all UW schools and colleges must complete one 5-credit composition (C) course from a list that can be found at: http://www.washington.edu/uaa/advising/degreeplanning/engcomp.php Students in the College of Arts & Sciences must complete two additional courses (designated by a W in the Time Schedule). A table showing the writing requirements for students in other colleges may be found at: http://www.washington.edu/uaa/advising/degreeplanning/gebsrofuwsc.php For Students: Writing Help for UW Undergraduates: Departmental writing centers and resources: History Writing Center: http://depts.washington.edu/histwrit/ Philosophy writing website: http://www.phil.washington.edu/PhilosophyWriting/index.html Psychology Writing Center: http://www.psych.uw.edu/psych.php#p=335 Sociology Writing Center: http://www.soc.washington.edu/undergraduate/soc-writing-center Political Science, Law, Societies and Justice, and School of International Studies Writing Center: http://depts.washington.edu/pswrite/ Campus-wide writing centers and resources: Odegaard Writing & Research Center: http://depts.washington.edu/owrc/ CLUE Writing Center: http://depts.washington.edu/clue/dropintutor_writing.php Instructional Center Writing Center, Office of Minority Affairs and Diversity: http://depts.washington.edu/ic/ Online exercises on writing mechanics (including some for ESL students) from A Writer’s Reference (6th ed) by Diana Hacker: http://bcs.bedfordstmartins.com/writersref6e/Player/Pages/Main.aspx Page 4 of 4 The Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) (206) 543-6588 | 100 Gerberding Hall | http://www.washington.edu/teaching.