Rhetoric OMG Reiff version

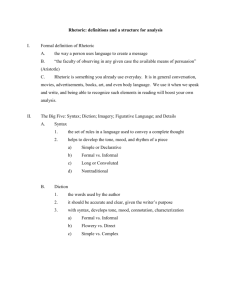

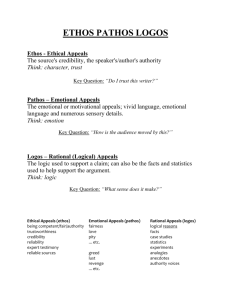

advertisement

Rhetoric Definitions and a Structure for Better Analysis Adapted from AP Collegeboard A Formal Definition of Rhetoric ● the way a person uses language to create a message ● “the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion” (Aristotle) In Other Words Rhetoric is something you already use everyday. It is in general conversation, movies, advertisements, books, art, and even body language. We use it when we speak and write, and being able to recognize such elements in reading will boost your own analysis. The Big Five Syntax Diction Imagery Figurative Language Details Syntax ● the set of rules in a language used to convey a complete thought ● helps to develop the tone, mood, and rhythm of a piece o o o o Simple or Declarative Formal vs. Informal Long or Convoluted Nontraditional Diction ● the words used by the author ● it should be accurate and clear, given the writer’s purpose ● with syntax, develops tone, mood, connotation, characterization o o o Formal vs. Informal Flowery vs. Direct Simple vs. Complex Details The details included within a piece of writing develop a writer’s tone, the mood of a piece, and the overall theme and style. What is included? What is omitted? How are the details structured or revealed? Imagery ● the use of figurative language to represent objects, actions, and ideas in a way that appeals to the senses ● this allows the reader to better understand the story concepts Figurative Language ● metaphors, similes, personification, onomatopoeia, allegories, symbols, ironies, etc., that, through word or structure create a figure or illustrative representation of something ● either makes a claim about something or reveals emotions and thoughts of the author/characters o these are both intended (author’s choice) and unintended (subconscious choices that reveal author’s psyche) The Rhetorical Triangle We’re drawing this. Yay! Draw a triangle in the middle of your paper. Then circle the triangle. Aristotle’s Elements- Speaker At the bottom left point of your triangle write the word “speaker”. Notes to add to the section: ● consider your own experiences, knowledge, and feelings to determine your attitude towards a subject and your understanding of the audience ● language, tone, style Aristotle’s Elements- Subject At the top of your triangle write the word “subject”. Notes to add to the section: ● evaluate what you know/need to know ● investigate perspectives ● determine needed evidence and proof Aristotle’s Elements- Audience At the bottom right of your triangle write the word “audience”. Notes to add to the section: ● determine reader’s expectations, knowledge, attitude towards your subject ● you consider this an assignment Context Inside your circle, write “context”. Add the following notes to this section: ● consider the circumstances or situation in which writing or speaking occurs ● examine the way context can lead to a writer’s rhetorical choices “We can’t know what writers mean...but we have rhetoric to help us interpret.” (Ann Berthoff) Aim, Intention, or Purpose On the edge of your circle write the word “Intention”. Notes to add to the section: ● the reason for a writer’s decisions ● effective writing analysis connects a writer’s purpose with a reader’s understanding ● often found within the thesis statement then carried throughout an entire piece Aristotle’s Appeals- Pathos (Emotion) ● Considering readers’ emotions and interests ● Shaping appeal for audience ● Using personal stories and observations ● Using figurative language to create drama and emotional reactions o imagery, metaphors, similes, analogies, etc. Pathos- What Not To Do ● Bandwagon o everyone else is doing it ● Flattery o sweet talk used to persuade ● In-crowd o if you adopt certain beliefs or values, you are cool ● Veiled threats o adverse consequences will occur if prescribed action is not taken ● False analogies o assuming that if two things are true in some ways, they are similar in other ways, without proof ● Weasel words o misleading, meaningless words or phrases Aristotle’s Appeals- Logos (Logic) ● Offering clear, thoughtful positions and support ● Developing ideas with appropriate details ● Using inductive and deductive reasoning ● Establishing cause and effect ● Providing examples, citing authority, using testimony Logos- What Not To Do ● Begging the question o statement based on something that hasn’t been proven ● Post hoc fallacy o assuming that one event caused another event when it could be coincidence ● Non sequitur o linking two unrelated ideas together ● Either-or o Simplifying a complicated situation to suggest there are only two outcomes Logos- More No-Nos ● Hasty generalization o utilizing stereotypes in an argument by making sweeping generalizations with little evidence ● Oversimplification o careless reasoning that is ignorant of all issues involved ● Slippery slope o assumption that one step will lead to a second, much more terrible, step ● Straw man o a diversionary fallacy that draws attention away from the argument Aristotle’s Appeals- Ethos (Credibility) ● ● ● ● ● Establishing common ground Demonstrating personal knowledge Providing credible support that is cited Demonstrating fairness Appealing to audience’s ethical or moral beliefs Ethos- What Not To Do ● Ad hominem o character attack (insulting person or cause instead of addressing argument or issue) ● Guilt by association o attacking a person’s associates to make person appear guilty or discredited (this is possible with ideas as well, by assuming an idea is flawed based on the creator or other associated ideas) Further explanation of the three appeals: Logos Logos: An appeal to logic. When a writer today employs logos, s/he might draw upon statistics, credible sources, arguments premised on reason, and the inherent logic of a situation. Consider this claim in a student paper about heart disease and pork-rind consumption: The information about the risks of eating pork rinds comes from no fewer than seven scientific studies published in respected journals. Each study was reviewed by a panel of readers who did not know the authors. The journals receive no outside funding except from their subscribers. Based on these factors, one must conclude that unless other studies come forward, pork-rind consumption poses health risks. Further explanation of the three appeals: Pathos Pathos: Appeals to emotion are common in non-academic writing but tend to distort factual evidence. From our pork-rind paper: When you see someone reaching for the pork rinds in the supermarket, you should slap it out of their hands and tell them the terrible story of these crunchy death-bags full of poison. Oh, consider the children who will grown up addicted to these vile things, unless we all act now! Pathos-based appeals can play on fears or other emotions. Advertising has elevated the use of pathos to a very fine art. Further explanation of the three appeals: Ethos Ethos: Can rely on reputation or experiences to prove a point. Credibility is key to winning an audience's belief and support for one's argument. Again, from the same paper: Darleen Diggler of Greasy Bottom, VA, was the first to testify at the Congressional hearing on pork rinds. Ms. Diggler, who had suffered four heart attacks, needed assistance getting into the chair provided her by the Congressmen. As she testified, "see what a pound of rinds a day will do to you! I've been eating them for thirty years! Now it is too late." She broke down, sobbing, at this point. Ms. Diggler's testimony was followed by Dr. I.M. Smarte, an award-winning cardiologist from the Medical College of Virginia. Dr. Smarte presented evidence from his four decades of practice, and he noted the high levels of saturated fat, trans-fat, and cholesterol found in pork rinds and urged Congress to pass the legislation outlawing the snack. Both Ms. Diggler and Dr. Smarte use ethos to make their claims; Smarte also employs logos (the claims about what the rinds contain). Diggler's plea could be seen as employing pathos to sway the lawmakers.