Continued Use of Illicit Substances: A Retention

advertisement

Oral Substitution Treatment for Opioid

Dependence: A Training in Best Practices &

Program Design for Nepal

Day 1

March 26-28, 2006

Kathmandu, Nepal

UNDP

Richard Elovich, MPH

Columbia

University Mailman School of Public

Health Medical Sociologist

Consultant, International Harm Reduction

Development International Open Society Institute

1

This Training is Adapted From:

Medication-Assisted Treatment For Opioid

Addiction in Opioid Treatment Programs

CSAT/SAMSHA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration Center for Substance Abuse Treatment)

2

Best Practices in Methadone Maintenance Treatment

Office of Canada’s Drug Strategy

Addiction Treatment: A Strengths Perspective

Katherine van Wormer and Diane Rae Davis

Additional Sources: Robert Newman, MD, Alex Wodak,

MD, Melinda Campopiano, M.D, Miller and Rollnick,

Prochaska, DiClemente, and Norcross, Michael Smith,

MD, Sharon Stancliff, MD, Ernest Drucker, PhD,

Adequate

Resources

Program Development

And

Design

Accessibility

3

A

Maintenance

Orientation

Training Goals

Ideally, this training will contribute to:

4

Increased knowledge, skills and best

practices among OST practitioners and

providers;

Engagement and retention of clients/patients

in the OST program in Kathmandu

Improved treatment outcomes

Six Training Modules

5

The SocioPharmacology of Opioid

Use and Dependence

Introduction and

background of oral

substitution treatment

The pharmacology of

medications used in oral

substitution treatment

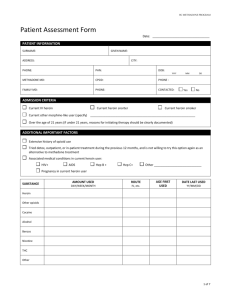

Information collection

and service provision:

‘assessment-in-action’

Pharmacotherapy and

OST

Insights from the field

Learning Together

Parallel Process

6

Learning Process: Knowledge and

Skills

Acquisition of content

Retention (store in memory)

Application (retrieve and use)

Proficiency (integrate and synthesize)

7

Expectations for Certification:

Training Contract

8

This is an 18 hour

training over a 3 day

period. Allowances have

been made for your work

schedules: Noon – 6 PM.

You must be present and

participate in all 18 hours

of the training to receive

certification. There can

be no exceptions.

Please stay focused. Be

on task because we have

a lot of material to cover

in 3 days.

Listening is a key to this

training. Listen to new ideas.

Listen to what’s coming up

inside you in relation to what’s

being presented. Try to put

your thoughts and feelings into

words instead of “shutting

down.”

Acknowledge and respect

differences. You can “agree to

disagree” on a contentious

point and move on. Participate

in role plays. Everyone has

permission to pass. Offer

feedback constructively not

personally. Try to receive

feedback as a gift.

Learning Environment

9

Try to be okay with

taking some learning

risks. Stretch past

your edge of what

you know and what

you are comfortable

with.

Confidentiality. Hold

the container. Don’t

be leaky.

Turn

off

phones

please.

No cross talk. Allow one

person to speak at a

time. Equal time over

time.

Start and end on time,

including breaks.

Be

alert to tendency to fudge

this.

Use “I” statements.

Can everybody agree to

this training contract? Is

there

anything

you

absolutely cannot live

with?

Now we are off.

I. The Socio-Pharmacology of

Opioid Use and Dependence

10

Heroin/Tidigesic/’Set’ Use= Social

Heroin/opiate use, though physiological and

experienced in the body, is socially mediated.

What does this mean?

11

Initiation– relational, social

Learning to use the drug.

Administration

The experience changes over time

Managing the experience

Contingencies

What else?

The production of getting “off” or

getting “high”.

12

Brainstorm components of the production.

List names of the social actors involved in the

production.

Identify social interactions.

Identify cognitive and learning processes.

Identify strategies of the heroin user or addict.

What is Opioid dependence?

13

14

“Drug Use is The Root of Their

Problems”

15

Substance use may be an expression of a

problem rather than its cause.

Rather than the cause of erratic or unhealthy

behavior, substance use may be an adaptive

mechanism or best solution to a range of

problems including mental illness, abusive

partner, homelessness, sexual abuse, poverty

or other difficulties (Springer, 1991)

“Bad Drug Using Women”

16

A survey of crack-using women in New York, for

example, found that nearly 1/3 had a past

history of abuse and prior hospitalization for

mental illness (Chavkin, 1993).

In another, women who were HIV+, were

homeless in the last year, and had experienced

combined physical and sexual abuse were also

those most likely to report exchanging sex for

drugs and money, using injection drugs in the

past year, and having sex in crack houses (El

Bassel et al, 2001).

“An Addict Stays the Same or

Gets Worse.”

17

Addiction is cyclic and variable in intensity.

While some addicts may follow the

pattern, made familiar by alcoholism, of

chronic, progressive illness, others may

have periods of intense drug use and

dysfunction followed by long periods of

being drug free or vice versa (Kane,

1999).

Compare cocaine bingeing and heroin

“It’s Their Choice; it’s Their Own

Fault.”

18

Ongoing substance use is rarely a simple

question of choice.

Much as with people in abusive

relationships or those with compulsive

disorders, “choice” for substance users is

shaped by perceptions of self-efficacy,

mental health status, and social

conditions.

“They stopped growing. They are not

themselves. They are addicted.”

19

How do we know they stop growing?

Who defines when people are themselves?

How do we define these terms? Societal or

cultural norms?

How does the “planet heroin” story lead us to

the disappearance of the person into the drug?

How are heroin users accounts of themselves

ignored or marginalized when we make these

assumptions based on the label addict?

“They are manipulative. They lie.”

20

Once a person is labeled a heroin addict,

what assumptions do we make about

them?

How are they treated by health providers?

Imagine yourself at your last job interview.

“Whose Fault is it Anyway?”

21

Addiction– like hypertension, asthma, or

diabetes– is chronic, relapsing condition whose

etiology frequently includes a combination of

behavioral, genetic, and environmental factors.

As with substance users, only a minority of

diabetics or hypertensives successfully abstain

from the behaviors contributive to these

conditions, yet these patients are not

stigmatized, blamed for their condition, or

denied health services (McLellelan et al, 1995)

1. How Do Drugs Work?

Drug Action: Interconnection between

neurology, the science of the nervous system,

and chemistry

Drug Effects represents broader phenomena

than drug and living tissue association.

Drug Factors, which originate outside the

laboratory, in real life practice that shapes

effects.

22

Drug Action I

23

In passing through the brain, a given drug (the

“key”) will be attracted to, and will bind to a

specific site in the brain (the lock).

The sites in the brain that control certain organs

are rich in receptors into which specific drugs

“fit” much like a key into a lock; these same sites

may lack receptors for other drugs.

Drug Action II

24

For instance, after heroin turns into

morphine in the body, morphine “fits into”

the receptors in the brain that control

breathing and heartbeat rate, and hence,

a sufficiently large dose of this drug can

shut down these two functions and cause

death by overdose.

Opiates: Duration of action

25

Methadone

Oxycontin

Heroin

Dilaudid

Codeine

Demerol

Fentanyl

24 hours

12 hours

6-8 hours

4-6 hours

3-4 hours

2-4 hours

1-2 hours

Heroin In The Brain

26

Short-term Effects Of Heroin Use

27

Soon after injection (or inhalation), heroin

crosses the blood-brain barrier.

In the brain, heroin is converted to

morphine and binds rapidly to opioid

receptors.

Abusers typically report feeling a surge of

pleasurable sensation, a "rush."

Short-term Effects Of Heroin Use

28

The intensity of the rush is a function of how

much drug is taken and how rapidly the

drug enters the brain and binds to the

natural opioid receptors.

Heroin is particularly addictive because it

enters the brain so rapidly.

Short-term Effects Of Heroin Use

With heroin, the rush is usually accompanied

by

The rush may also be accompanied by

29

A warm flushing of the skin,

Dry mouth, and

A heavy feeling in the extremities,

Nausea,

Vomiting, and

Severe itching.

Short-term Effects Of Heroin Use

30

After initial effects, drowsy for several hours.

Mental function clouded by effect on CNS.

Cardiac function slows.

Breathing severely slowed, sometimes to

the point of death.

Overdose is a particular risk on the street,

where the amount and purity of the drug

cannot be accurately known.

Short-term Effects Of Heroin Use

31

“Rush”

Depressed Respiration

Clouded Mental Functioning

Nausea and Vomiting

Suppression of pain

Spontaneous abortion

Heroin Intoxication

32

Pupil size (pinned pupils)

Voice (slower, lower in tone)

Conversations (talkative)

Being high (feeling warm, euphoric, content)

Scratching

Droopy eyes

Itchiness?

Blood spots (needle marks bleed)

Expansive mood

Nodding out (sleep-like state)

Drug Action and Drug Effects

33

It is crucial to make a distinction between

the specific pharmacological action of a

drug, which is the product of a biological

and chemical process, and drug effects.

Drug Effects

34

Drug effects is far more than the chemistry of a

drug placed in the setting of living tissue. They

represent the nonspecific factors that influence

drug effects.

Six more or less pharmacological dimensions:

(1) identity and half-life in the body; (2) dose; (3)

potency and purity; (4) drug mixing; (5) route of

administration; (6) habituation.

Five additional factors that originate outside

the laboratory setting in real life practice

35

Set

Setting

Script

Schedule (раскумарчтвся or morning shot)

Structure

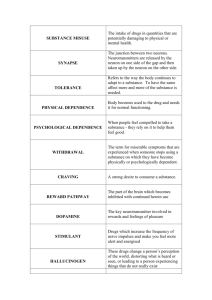

Tolerance

Need for increased amounts of

the drug to achieve desired effect

Markedly diminished effect with

continued use of the same

amount of the drug

Withdrawal

36

Characteristic withdrawal

syndrome

The same (or closely related) drug

is taken to relieve or avoid

withdrawal symptoms

The drug is taken in larger

amounts or over a longer period

than was intended

There is a persistent desire or

unsuccessful efforts to cut down

or control drug use

A great deal of time is spent in

activities necessary to obtain the

drug

Important social, occupational or

recreational activities are given up

or reduced

Drug use is continued despite

knowledge of having a persistent

or recurrent problem that is likely

to have been caused or

exacerbated by the drug use

What is Substance Dependence

37

As the DSM IV explains, the term “addiction” is no longer

widespread in the medical community, and has been

widely replaced by the term “drug {or substance}

dependence. They also note that the term “drug {or

substance abuse} abuse” is:

“a highly complex, value-laden and often excessively

vague term that does not lend itself completely to any

single definition.”

Furthermore, because the term has different meanings

for different groups of people– and their definition of the

term reflects their different perspectives– there is often

difficulty in drawing a line between use of substances

and abuse of substances (Brands et al., 1998, 45).

Dependence Syndrome

38

Dependence syndrome consists of the particular

behavioral, cognitive and physiological effects that may

arise through repeated substance use.

Psychological characteristics include a strong desire

to take the drug (craving), impaired control over its use,

persistent use despite harmful consequences, and the

prioritization of drug use over other activities and

obligations.

Physical dependence comprises increased tolerance

and a physical withdrawal reaction that occurs when

drug use is discontinued (WHO 1984)

The DSM-IV* Specifies Criteria

for Opioid Dependence:

“A maladaptive pattern of substance use, leading to

clinically significant impairment or distress, as

manifested by three (or more) of the following,

occurring any time in the same 12-month period:

tolerance, as defined by either of the following:

a)

b)

A need for markedly increased amounts of the substance to

achieve intoxication or desired effect

Markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same

amount of the substance.

*American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

of Mental Disorder (DSM-IV)

39

The DSM-IV Specifies Criteria for

Opioid Dependence:

Withdrawal, as manifested by either of the

following:

a)

b)

40

The characteristic withdrawal syndrome for the

substance

The same (or a closely related) substance is taken

to relieve or avoid withdrawal symptoms

The substance is often taken in larger amounts

or over a longer period than was intended

There is a persistent desire or unsuccessful

efforts to cut down or control substance use

The DSM-IV Specifies Criteria for

Opioid Dependence:

41

A great deal of time is spent in activities

necessary to obtain the substance, use the

substance, or recover from its effects

Important social, occupational, or recreational

activities are given up or reduced because of

substance use

The substance use is continued despite

knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent

physical or psychological problem that is likely

to have been caused or exacerbated by the

substance

Perspectives on Drug

Dependence

42

The unfolding nature of heroin

dependence

Different types of dependencies and

patterns of practices. Drug dependence is

complex and variable but literature speaks

in absolutes

Fluid phenomenon: movable famine

Drug users are thinking, strategizing

Range of different therapies/services for

multiple and incremental outcomes

Tolerance and Habituation

43

When a person uses heroin regularly, they

develop a tolerance– they have to use more

heroin to get the same effects. The greater the

amount and frequency of their use, the faster

they become tolerant.

Some people try to “chip” or use only

occasionally, avoiding two days in a row.

Others try to “manage their habits” by using a

little less for a day or two to lower their

tolerance, allowing them to decrease the

amount needed to get high-- or well.

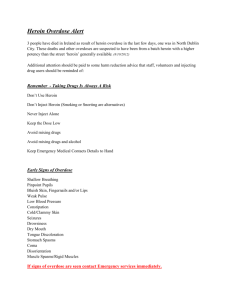

Overdose

44

Overdose is a serious health risk for

heroin users.

Heroin slows down the heart rate and

breathing; someone who overdoses may

eventually stop breathing altogether.

Mixing heroin with other drugs (valium,

alcohol, cocaine) significantly increases

risk of overdosing, especially alcohol.

Active Drug users can be

approached about overdosing:

45

Avoid mixing heroin with other drugs,

especially “benzos” (Xanax, Clonopin,

Ativan, Valium), other “downs” (Seconal,

Elavil, Placidyl) or alcohol.

Many drug users overdose after coming

out of jail because their tolerance has

fallen. Users should do a tester shot if it is

from a new source or they have not used

in a while.

Overdose are very serious but do

not have to be fatal:

46

Drug users should talk with using partners and

make a plan for dealing with ODs. If they have

thought it through, they are less likely to panic or

freeze up in the event of an actual OD.

Drug users should know about Naloxone, what

paramedics use, and can call 1 866 STOP ODS

for more information.

Drug users can learn rescue (mouth to mouth)

breathing, which is the most important thing they

can do to help someone survive an overdose.

Heroin Withdrawal (1 of 2)

47

Elevated Blood Pressure & Pulse

Insomnia (can last for days or weeks)

Restlessness

Anxiety (confusion, exaggerated startle reflex)

Irritability

Body aches

Lacrimation

Sneezing

Heroin Withdrawal (2 of 2)

48

Runny nose

Piloerection (body hair stands up)

Nausea and vomiting (can lead to dehydration)

Sweating

Diarrhea

Deep muscle twitch

Spontaneous erection or ejaculation (due to

hypersensitivity)

Pupil dilation (enlarged pupils)

Long-term Effects Of Heroin Use

49

Dependence

Infectious Diseases: HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis B & C

Collapsed veins

Bacterial Infections

Abscesses

Infection of heart lining and valves

Arthritis and other rheumatologic problems

Long-term Effects Of Heroin Use

Physical dependence develops with higher

doses of the drug.

50

The body adapts to the presence of the drug

and withdrawal symptoms occur if use is

reduced abruptly.

Withdrawal may occur within a few hours after

the last time the drug is taken.

Long-term Effects Of Heroin Use

Symptoms of withdrawal include:

51

Restlessness

Muscle and bone pain

Insomnia

Diarrhea

Vomiting

Cold flashes with goose bumps ("cold turkey")

Leg movements.

Long-term Effects Of Heroin Use

52

Major withdrawal symptoms peak 24 - 48

hours after the last dose of heroin and

subside after about a week.

Some people have shown persistent

withdrawal signs for many months.

Heroin withdrawal is never fatal to otherwise

healthy adults, but it can cause death to the

fetus of a pregnant addict.

Chronic Use: Medical

Complications

53

Scarred and/or collapsed veins

Bacterial infections of blood vessels and heart

valves

Abscesses (boils) and other soft-tissue infections

Liver or kidney disease

Lung complications (e.g., pneumonia, TB) may

result from the poor health condition of the abuser

as well as from heroin's depressing effects on

respiration.

Sources of Skin Infections

54

User’s skin and mouth (most common)

Syringe

Cooker

Dissolving water

Filter

Drugs and contaminants

Danger Signs

Fever and chills

Increased pulse

Difficulty breathing

Altered mental status/confusion

Can progress to

55

Sepsis

Necrotizing fascitis (gangrene, streptococcus)

Wound botulism or tetanus

Prevention of Infection

56

New needle for each injection or reduction

in reuse

Site rotation

Alcohol wipes or soap and water for at

least one minute

Cook heroin until it bubbles

Plan for missing the vein

Chronic Use: Medical

Complications

57

Clogging of blood vessels that lead to the

lungs, liver, kidneys, or brain (due to the

many additives in street heroin which may

not readily dissolve) resulting in infection or

even death of small patches of cells in vital

organs.

Immune reactions to these or other

contaminants can cause arthritis or other

rheumatologic problems.

Chronic Use: Medical

Complications

58

Sharing “works” or fluids can lead to some of

the most severe consequences of heroin

abuse-infections with hepatitis B and C, HIV,

and a host of other blood-borne viruses,

which drug abusers can then pass on to their

sexual partners and children.

Heroin Abuse & Pregnancy

59

Heroin abuse can cause serious

complications during pregnancy,

including miscarriage and

premature delivery.

Children born to addicted

mothers are at greater risk of

SIDS (Sudden Infant Death

Syndrome), as well.

Heroin Abuse & Pregnancy

60

Pregnant women should not be detoxified from opiates

because of the increased risk of spontaneous abortion or

premature delivery; rather, treatment with methadone is

strongly advised.

Infants born to mothers taking prescribed methadone may

show signs of physical dependence but they can be treated

easily and safely in the nursery.

Research has demonstrated also that the effects of in utero

exposure to methadone are relatively benign.

Heroin Use & Blood-borne Diseases

61

At risk for contracting HIV, hepatitis C, and other

infectious diseases through sharing and reusing

syringes and injection paraphernalia that have

been used by infected individuals.

They may also become infected with HIV and,

although less often, to hepatitis C through

unprotected sexual contact with an infected person.

Injection drug use has been a factor in an

estimated one-third of all HIV and more than half of

all hepatitis C cases in the Nation.

Heroin Use & Blood-borne Diseases

Users can change the behaviors that put them at

risk for contracting HIV, through drug abuse

treatment, prevention, and community-based

outreach programs, including harm reduction.

Users can reduce or eliminate the risk of exposure

to HIV/AIDS and other infectious diseases by

decreasing/eliminating:

62

drug use

Injection drug use

drug-related risk behaviors such as needle sharing

unsafe sexual practices

II. Introduction and background of

oral substitution treatment

63

What is Oral Substitution Therapy (OST)?

How does Methadone Work?

Rationale for and Uses of OST

What types of OST are Most Effective?

Increasing Access to OST in Nepal:

Identifying and Overcoming Barriers

Developing a Continuum of MMT Program

Delivery

Vernacular Formulations of

Substitution Therapies

64

Irregular supply, fluctuations in price and

purity mean dangers for drug users and

others

Drug users are already creating their own

forms of replacement therapy

Although we call it ‘methadone

maintenance,’ it is a form of drug

treatment

65

66

67

68

69

70

The Basic Orientation

71

THE PATIENT: like all other patients

THE CONDITION: like all other chronic medical

conditions

THE MEDICATION: like all others used in medicine

CHINA VISIT

APRIL 7-14, 2005

The Baron Edmond de Rothschild

Chemical Dependency Institute

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

What is Methadone?

Formulation: Oral solution, liquid

concentrate, tablet/diskette, and powder

Receptor Pharmacology: Full mu, opioid

agonist

Regulation: Proscriptive regulations fail to

leave room for treatment flexibility and

innovation (SAMSHA, U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services: Treatment Improvement Protocol 43: 22)

82

How Does Methadone Work? 1

83

Opiate agonists bind to the mu opiate

receptors on the surfaces of brain cells,

which mediate the analgesic and other

effects of opioids.

Methadone produces a range of mu

agonist effects similar to those of shortacting opioids.

How Does Methadone Work? 2

84

Therapeutically appropriate doses of this agonist

medication produce cross-tolerance for short

acting opioids such as morphine and heroin,

thereby suppressing withdrawal symptoms and

opioid craving as a short-acting opioid is

eliminated from the body. The dose needed to

produce cross-tolerance depends on the

individual patient’s level of tolerance for shortacting opioids.

How Does Methadone Work? 3

85

When given intramuscularly or orally,

methadone suppresses pain for 4 to 6

hours. Intramuscular is used only for

patients who cannot take oral methadone,

for example, patients in medicationassisted treatment for opioid dependence

who are admitted to a hospital for

emergency medical procedures.

How Does Methadone Work? 4

86

Methadone is metabolized chiefly by the

cytochrome P3A4 (CYP3A4) enzyme

system (Oda and Kharasch 2001), which

is significant when methadone is coadministered with other medication that

also operate along this metabolic pathway.

How Does Methadone Work? 5

87

After patient induction into methadone

pharmacotherapy, a steady-state

concentration (i.e., the level at which the

amount of drug entering the body equals

the amount being excreted) of methadone

usually is achieved in 5 to 7.5 days (four to

five half-lives of the drug).

How Does Methadone Work? 6

88

Methadone’s pharmacological profile

supports sustained activity at the mu

opiate receptors, which allows substantial

normalization of many physiological

disturbances resulting from the repeated

cycles of intoxication and withdrawal

associated with dependence on shortacting opioids.

How Does Methadone Work? 7

89

Therapeutically appropriate doses of methadone

also attenuate or block the euphoric of heroin

and other opioids.

When opiate medication dosage must be

adjusted to compensate for the effects of

interacting drugs (e.g., Rifampin for TB),

observe patients for signs or symptoms of opioid

withdrawal or sedation to determine whether

they are under medicated or overmedicated.

How Does Methadone Work? 8

90

Methadone is up to 80% orally

bioavailable, and its elimination half-life

ranges from 24 to 36 hours. When

methadone is administered daily in steady

oral doses, its level in blood should

maintain a 24-hour asymptomatic state,

without episodes of overmedication or

withdrawal (Payte and Zweben 1998).

How Does Methadone Work? 9

91

Methadone’s body clearance rate varies

considerably between individuals. The serum

methadone level (SML) and elimination half-life

are influenced by several factors including

pregnancy and a patient’s absorption,

metabolism and protein binding, changes in

urinary pH, use of other medications, diet,

physical conditions, age, and use of vitamin and

herbal products (Payte and Zweben 1998).

Early Research Findings Vincent P. Dole

1980, 1988

Patients do not experience euphoric,

tranquilizing, or analgesic effects. Their

affect and consciousness were normal.

Therefore, they could socialize and work

normally without the incapacitating effects

of short-acting opioids such as morphine

or heroin

(SAMSHA, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Treatment

Improvement Protocol 43: 17-18)

92

Early Research Findings Vincent P. Dole

1980, 1988

A therapeutic, appropriate dose of

methadone reduced or blocked the

euphoric and tranquilizing effects of all

opioid drugs examined, regardless of

whether a patient injected or smoked the

drugs (e.g., morphine, heroin, opium, etc.)

(SAMSHA, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Treatment

Improvement Protocol 43: 17-18)

93

Early Research Findings Vincent P. Dole

1980, 1988

No change usually occurred in tolerance levels

for methadone over time, unlike for morphine

and other opioids; therefore, a dose could be

held constant for extended periods (more than

20 years in some cases.)

Methadone was effective when administered

orally. Because it has a half-life of 24-36 hours,

patients could take it once a day without a

syringe. (SAMSHA, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services:

Treatment Improvement Protocol 43: 17-18)

94

Early Research Findings Vincent P. Dole

1980, 1988

Methadone relieved the opioid craving or hunger

that patients with addiction described as a major

factor in relapse and continued illegal use

Methadone, like most-opioid class drugs,

caused what were considered minimal side

effects, and research indicated that methadone

was medically safe and nontoxic.

(SAMSHA, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Treatment Improvement

Protocol 43: 22)

95

Expansion of Methadone from

Research to Public Health Program

96

Most patients were stabilized on methadone

doses of 80 to 120 mg/day.

Most patients who remained in treatment

subsequently eliminated illicit-opioid use.

In general, the team found that patients’ social

functioning improved with time in treatment, as

measured by elimination of illicit-opioid use and

better outcomes in employment, school

attendance, and domestic relations.

Columbia University School of Public Health, Dr. Frances Rowe Gearing, 1974

Poly Substance Use and Abuse

97

However, 20 percent of more of these patients

also had entered treatment with alcohol and poly

substance abuse problems., despite intake

screening that attempted to eliminate these

patients from treatment. (Gearing and Schweitzer 1974)

Methadone treatment was continued for these

patients, along with attempts to treat their

alcoholism and polysubstance abuse.

MMTP Becomes A Major Public

Health Initiative in the U.S.

98

Methadone maintenance became a major public

health initiative to treat opioid dependence

under the leadership of Dr. Jerome Jaffe, who

headed the special Action Office for Drug Abuse

Prevention in the Executive Office of the White

House in the early 1970s.

Dr. Jaffe’s office oversaw the creation of a

nationwide , publicly funded system of treatment

programs for opioid dependence

The pharmacotherapy of opiate

dependence

Robert Newman, MD,

Director, Baron Edmond de Rothschild Chemical Dependency Institute

Beth Israel Medical Center, NYC

Presented @ the 15th INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE

ON THE REDUCTION OF DRUG RELATED HARM,

Melbourne, Australia, 20-24 April, 2004

99

The Baron Edmond de Rothschild

Chemical Dependency Institute

Methadone Maintenance (MMT).

Dole and Nyswander, 1964

Their goal: “… to look for some

medication to permit addicts to live as

normally as possible” *

Initial study ** with 22 “subjects”

“Maintenance dose” ranged from 10180mg

No reference to any preferred duration of

treatment

100

Methadone: seeking to explain success

Dole and Nyswander, 1967

“The unexpected response to a

simple medical program forced us to

re-examine our assumptions”

“We had been misled by traditional

theories based on weaknesses of

character.”

101

Addiction: A theory

Dole, 1970

“Persistent physiological changes

contribute – somehow! – to relapse

tendency after abstinence has been

achieved.”

102

Dole. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 30:821-840, 1970

1973 - support for the theory:

Opiate receptors/peptides in brain

“Identification of opiate receptors

provides insight into mechanism of

action of opiates.” *

Brain “contains substances with

morphine-like activity”**

103

“High on methadone?” No!

“We have not been able to find a medical or

psychological test capable of identifying patients

on methadone.”*

When given placebo “patients were unaware that

the medication had been changed” until

withdrawal began**

“Methadone given in constant daily doses causes

no euphoria, abstinence symptoms or demand for

escalation of dose.”**

* Dole and Nyswander. JAMA. 193(8):646-650, 1965

** Dole and Nyswander. NY State J of Med. 66(15):2011-2017,

1966

104

Methadone effectiveness and safety

US Government assessment, 1983

Retains more patients, longer, than any other

treatment

Heroin use and criminal activity significantly reduced

Employment increases

Marked improvement in health status

No major adverse consequences

Dosage/duration limits “therapeutically unjustified”

US National Institute on Drug Abuse DHHS publication

(ADM)83:1281, 1983

105

US Government on Methadone –

consistency! 1983-2004

1997: “Methadone significantly lowers illicit

opiate use and related illness and death,

reduces crime, enhances social

responsibility.”*

2004: “Methadone continues to be a safe

and effective treatment for addiction to

heroin.”**

* NIDA Notes, 1997,

http://www.drugabuse.gov/NIDA_Notes/NNVol12/NIPanel.html

** Subst. Abuse and Ment. Heath Services Admin., News release

6 Feb 2004

106

United Nations on harm reduction

and methadone, 2003

“UNODC is particularly committed to programmes

that reduce harm from drug abuse.”

“It is important to implement methadone

programmes urgently.”

Speech by Dr. Sandro Calvani, UNODC Regional Representative for East Asia

and the Pacific, given in Hong Kong 22 Oct. 2003

107

WHO/UNODC/UNAIDS

Position paper on “substitution”, 2004

“Maintenance treatment is an

effective, safe, cost-effective

modality.”

Available on line: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/

108

When there’s commitment . . .

Hong Kong, 1975-76

End 1974:

one “pilot” programme, 500

patients

End 1975: approximately 2,000 enrolled

End 1976: approximately 10,000 enrolled

Admissions to voluntary in-patient drugfree programmes stable 1974-76: 2,3002,500/year

109

Newman J. Pub. Health Policy 6(4):526-538 (1985)

Roughly: For a

problem with heroin,

call this number for

same-day help!

110

Risk of HIV Infection in Hong Kong

(1984-2002)

160

140

120

100

80

60

40

20

Heterosexual

Homosexual/bisexual

Injecting Drug Use

20

02

20

01

20

00

19

99

19

98

19

97

19

96

19

95

19

94

19

93

19

92

19

91

19

90

19

89

19

88

19

87

19

86

19

85

19

84

0

Other/Unknown

Source: HIV Surveillance Report 2002 Update (Dept of Health, Hong Kong S.A.R., Nov 2003)

111

When there’s commitment . . .

Croatia 1991-present

Treatment started 1991; GPs mainstay of

MMT

Of 2,400 GPs nationally, over 1,000

provide MMT

High retention – 70-80%

Estimated 15,000 heroin addicts; 7,000

get Rx

112

Ivancic SEEA Addiction 4(1-2):15-17, 2003

Estimated number of patients receiving

methadone & buprenorphine in France, 1996-2001

Source: on web at http://www.drogues.gouv.fr/fr/professionnels/etdues_recherches/IT-4b.pdf

113

Ancient history

Dr. Ernest Bishop (NYC), 1920

“We have regarded failure to abstain from

narcotics as evidence of weak will-power.”

“We have prayed over our addicts, cajoled

them, exhorted them, imprisoned them,

treated them as insane and made them

social outcasts” – and we’ve consistently

failed!

114

Bishop, The Narcotic Drug Problem. Macmillan; NY 1920

Stepped Approach vs. All or Nothing

Approach

115

Optimal: drug cessation

Reduce drug use

Increased control of drug use

Alternative to injecting

Alternative to sharing

Reduce harm related to sharing and safer

sex practices

The Context for OST in Nepal

Heroin

Tidigesic (Buprenorphine)

The “Set”:

116

Norphine

Diazapam

Avil

The Subjective Meanings of Injecting