Kinyan - Machal

advertisement

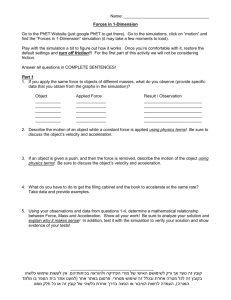

פרשת תרומה A basic term in Halachah is קנין. Kinyan is an acquisition. A person is able to acquire an object by virtue of an act that the Torah imbues with the power to allow a meaningful transaction1. A Kinyan is used when one acquires something that has no owner, i.e. it was hefer or to acquire something that belonged to someone else and by virtue of the Kinyan, the ownership is transferred from the previous owner to the new owner. Kinyan is not a robotic act. That is to say, the act of Kinyan in and on its own does not affect transfer of ownership. Except for the case when one is acquiring an object which was made hefker, an essential component to transfer ownership is that of דעת מקנה. Da’as mak’neh means that the person who is the present owner wishes to affect a transfer of ownership. In the absence of דעת מקנה, the act of acquisition has no meaning or validity. In general, the acts that are valid for acquisition include הגבהה, lifting up the acquired object, משיכה, pulling the acquired object or מסירה, when the previous owner hands the object to the new owner2. These are all means for the new owner to literally hold the object which he is acquiring3. The first Perek of Masseches Kiddushin serves as a primary source for the types of Beginning with the specifics of acquisition of marriage and then of slaves, the Mishnah than expands its discussion to general rules. Some of those Mishnayos will be cited below. 1 Kinyonim and their laws. The multiplicity of kinyanim does not mean that all are valid with all types of objects. It could be that an article that could be lifted, i.e. acquired with the kinyan of הגבההcould not be acquired with the other acts of acquisition. 2 The Mishnah (ibid. 25 b) writes: בהמה דקה: דברי רבי מאיר ור' אליעזר; וחכמים אומרים, בהגבהה- והדקה,בהמה גסה נקנית במסירה .נקנית במשיכה A large animal is acquired through transfer. A small animal-through lifting, these are the words of Rabi Meir and Rabi Eliezer. The Chachamim say, ‘a small animal is [also] acquired through pulling. 3 In the event that real estate is being transferred, and there is no way to literally hold the object, an act that demonstrates ownership is required. Such an act is called חזקה. Chazakah, in this context, means ‘possession’ or ‘holding-on’ to the object. Some examples of chazakah are making improvements on property and planting and harvesting crops. Real estate is also acquired by contract and by monetary payment4. There are additional types of Kinyan, too, but the above are the basic acts that demonstrate that a person owns the property with which he is dealing5. In our Parshas Terumah, we wish to ask a question regarding Kinyan. Our ancestors were asked to make a donation to the building of the Mishkan. Specific items were necessary for its construction and they are enumerated in our Parsha. By what mechanism did those donated objects the property of the soonto-be Mishkan? We read in our Parsha (Perek 25/Posuk 2): :דבר אל בני ישראל ויקחו לי תרומה מאת כל איש אשר ידבנו לבו תקחו את תרומתי We read in the Mishnah (ibid. 26 a): . אין נקנין אלא במשיכה- שאין להם אחריות, נקנין בכסף ובשטר ובחזקה- נכסים שיש להם אחריות Property that has security is acquired with payment, contract and chazaka. Property that does not have security in only acquired with pulling. 4 Rashi explains that real estate is called property that has security because if someone lends money to the owner of such property he is secure in his knowledge that he will be able to collect the debt from the property if the borrower defaults. The Mishnah cited in note 4 continues: ובחזקה, ובשטר, בכסף- נכסים שאין להם אחריות נקנין עם נכסים שיש להם אחריות Insecure property can be acquired with secure property which is acquired with payment, contract or chazaka. 5 In the Gemara this type of acquisition is called קנין אגב קרקעwhich means that one acquires non-real estate by virtue of the acquisition of real estate. Of course, this is a convenient type of acquisition because with the payment for the real estate, the other properties are acquired without having to make an individual act of acquisition on each and every object where it happens to be. Speak to B’nei Yisroel and they should take for Me teruma, from each man of Israel whose heart will donate, you should take My teruma. It is clear that the teruma will be eventually collected. That is implied by the end of the verse that reads תקחו תרומתי-you should take My teruma. However, the initial stage is done completely by the individual. ויקחו לי תרומהthey, the householders, should take My Teruma. If the householder takes an object from himself, how does it become teruma? Where is the transfer of ownership6? We learn in the Mishnah in Masseches Kiddushin (28 b): אמירתו לגבוה כמסירתו להדיוט His “saying” (or even ‘thinking’7) for hekdesh8 is the same as his transfer9 for nonhekdesh10. Further on we will discuss the source for the principle about to be discussed. It would seem that this verse could also serve as the source for the principle that the means of sanctifying an object, that is transferring it to the possession of the Mishkan/Beis HaMikdosh can be accomplished without the participation of the ‘body’ that will make the acquisition. I searched to see if someone would relate to this point but I have not found anyone who discusses it. Perhaps, then, there is a flaw that I have not yet discovered. 6 Although the term used here is אמירתו, his ‘saying’, in regards to the sanctification of objects, הקדש, it is not necessary to utter the words. In fact, a מחשבה, thought, is sufficient to transform a non-sanctified item to a state of sanctity. In Masseches Shavuos 26 b we read: כב ויבאו האנשים על הנשים) כל נדיב לב/ (שמות לה: גמר בלבו מנין? ת"ל,אין לי אלא שהוציא בשפתיו .)'(הביאו חח ונזם וטבעת וכומז כל כלי זהב וכל איש אשר הניף תנופת זהב לה 7 I only know [that an object can be sanctified] when he expressed this with his lips, if he decided in his heart [without saying that he is sanctifying the object] from where do we know [that the object is sanctified]? Because it says “…every donation of the heart brought the gifts to the Mishkan. Thus we see that a decision ‘in the heart’, that is in one’s thought can accomplish the act of sanctification. Rashi notes an additional verse in Divrei HaYomim II (Perek 29/Posuk 31): ויען יחזקיהו ויאמר עתה מלאתם ידכם לה' גשו והביאו זבחים ותודות לבית ה' ויביאו הקהל זבחים :ותודות וכל נדיב לב עלות Chizkiyahu (the king) responded and said, ‘now you have dedicated yourselves to Hashem, approach and bring offerings and thanksgivings to Hashem and the people brought offerings and thanksgivings to Hashem, every donor of the heart brought Olos-burnt offerings. By using the phrase נדיב לבwe understand that the sanctification of these offerings was done by thought, not by expressing the thought in words. The addition of this verse removes a possible question that could have been raised. In the Torah, in our Parshas Terumah and the other instances where phrases like נדיב לבare used, it is always in the context of building the Mishkan. It is not in the context of the korbonos that will be offered there. Thus, one may think that to dedicate materials to build the Mishkan, a thought is sufficient. To dedicate materials for the actual offerings to Hashem, though may be insufficient and I require a clear declaration-one that is uttered. Thus, the verse in Divrei HaYomim teaches us that נדיב לב, this dedication that comes about through thought alone, is valid for the korbonos as well. [Vis a vis the p’shat of the Posuk, the phrase נדיב לבis used in relationship to the Korbon ‘Oloh, the burnt-offering, and not to the other offerings mentioned in the verse. That is because in regard to the other offerings, people partake of Korbon, Kohanim and those who brought it. In regard to the ‘Oloh, however, no one partakes of it. it is completely burnt and thus one who donates the ‘Oloh, is particularly generous. Thus, in Parshas Tzav, when various aspects of the Korbon ‘Oloh are discussed, Hashem tells Moshe Rabbenu צו את בני ישראל, command Israel. Why was it necessary to add the word צו, command, when the very word of G-d is a commandment in and of itself? The Posuk (Vayikro Perek 6/Posuk 2) reads: צו את אהרן ואת בניו לאמר זאת תורת העלה הוא העלה על מוקדה על המזבח כל הלילה עד הבקר ואש :המזבח תוקד בו Command Aharon and his sons saying, This is the law of the ‘Oloh, it is the ‘Oloh that is on the fire on the altar all of the night until the morning and the fire of the altar will be inflamed in it. Rashi explains: אמר ר' שמעון ביותר צריך הכתוב לזרז במקום שיש בו. אין צו אלא לשון זרוז מיד ולדורות- צו את אהרן :חסרון כיס Command Aharon-Tzav is an expressing of urgency, for the moment and for all time. Rabi Shimon said, ‘in particular the verse had to urge in a place where there is a monetary loss. The Gemara there gives a clear example of the application of this rule: אפי' בסוף, בית זה הקדש,כיצד אמירתו לגבוה כמסירתו להדיוט? האומר שור זה עולה . בהדיוט לא קנה, קנה- העולם What is an example [of the application of this rule] that “His saying for hekdesh is the same as his transfer for non-hekdesh”? If one says, this ox is a Korban Oloh, this house is hekdesh-holy, even if they are at the other end of the world, [hekdesh] has acquired it, with a commoner - he did not acquire it. Thus, when the donor will say, ‘this gold is for the Mishkan’, this silver is for the Mishkan’, they are immediately imbued with sanctity and their use for a nonMishkan function is an act of 11מעילה. They are now holy objects. The word in the Mishnah is גבוה, that which is ‘high’ or above. It is unquestionable from the context that the Mishnah is referring to hekdesh with this term. 8 All the commentators note that the term מסירה-handing over in the Mishnah is not meant to denote a specific act of kinyan but is used here generically-representing the entire repertoire of Kinyanim that are valid for the various types of circumstances that exist. 9 The Mishnah uses the term הדיוטwhich is translated as commoner. However, the term hedyot is understood in relationship to its context. That is, if the context is a king, then הדיוטmeans a commoner, non-royalty. If the context is a Kohen, then a הדיוטcould mean a Levi or a Yisroel. We find the term מנהג הדיוט, a practice of commoners, to denote a practice which does not meet the standard of מנהג ישראלwhich is binding. Here the context is one of הקדשso hedyot means non-hekdesh. 11 The Torah forbids the misuse of hekdesh articles for non-hekdesh purposes. We read in Parshas Vayikro (Vayikro Perek 5/P’sukim 15-16): נפש כי תמעל מעל וחטאה בשגגה מקדשי ה' והביא את אשמו לה' איל תמים מן הצאן בערכך כסף ואת אשר חטא מן הקדש ישלם ואת חמישתו יוסף עליו ונתן אתו לכהן:שקלים בשקל הקדש לאשם :והכהן יכפר עליו באיל האשם ונסלח לו A person who acts fraudulently and sins without knowledge from the articles made holy for Hashem-he should bring his guilt-offering to G-d an unblemished ram from the sheep with the value of two shekolim in the valuation of the sanctified shekolim, for Hashem. He who sins from the sanctified objects should pay and add a fifth upon it and give it the Kohen and the Kohen should atone for him with the guiltoffering-ram and he will be forgiven. 10 Chazal tell us a source for this power of speech that is given to the individual vis a vis the sanctification of his property. The Yerushalmi on Masseches Kiddushin (Perek 1/Halachah 6) explains that this ability to sanctify an object merely by means of an oral declaration is learned from the Posuk in Tehillim (Perek 24/Posuk 1): לה' הארץ ומלואה תבל ויושבי בה. The land belongs to G-d, the entire earth and those who dwell upon it. By virtue of this verse, Meiri to our Gemara (Masseches Kiddushin 28 b) explains that the world is already in the possession of G-d. the Halachah teaches us that an object that is within the confines of one’s enclosed and secured property can be acquired by virtue of the fact that it is contained within his control. Meiri explains that the world is G-d’s enclosed and secure property and thus, merely, by giving expression to the decision to sanctify the object, it is already in G-d’s possession. Rashbam (Masseches Bava Basra 133 b) says that the source for the efficacy of an oral declaration to sanctify an objective his learned from the verse in the Torah (Vayikro Perek 27/Posuk 14): ואיש כי יקדש את ביתו קדש לה' והעריכו הכהן בין טוב ובין רע כאשר יעריך אתו הכהן כן :יקום When a man sanctifies his house to be holy for Hashem, the Kohen determines its value, for more or for less, as the Kohen determines its value so shall it be. Thus, an unintentional act of מעילהrequires a sacrifice, restituting whatever monetary loss that was caused to Hekdesh with the additional payment of a fine of one-fifth on the value of the principal. When the act of מעילהwas intentional, there is no offering and no monetary fine. It seems that Rashbam understands that the individual in question here declared the house to be sanctified and the Torah says “'”קודש לה, it is [=becomes] sanctified.12 Perhaps we can view this unique kinyan-process in another light as well. G-d introduced sanctity to man13. By virtue of enabling man to sanctify, Hashem enhanced his essence. With that enhanced essence that which would not be sufficient for a mundane kinyan becomes effective for a kinyan that introduces sanctity. That is, when a person sanctifies an object, he does so from the source of his own sanctity. His own sanctity is superior to his physicality and thus he does not have to do a gross motor act to give over the object to hekdesh. This higher-level declaration of sanctification, which stems from the higher level of being able to sanctify works on a rarefied level. The power of speech in the area of sanctification accomplishes what the hands and legs could accomplish in the mundane world. Thus, it is the increased sanctify of the act of sanctification which concretizes the words that a person utters and makes them as powerful as actual accomplished deeds. We know that we can divide our activities into three divisions: מעשה-deed, דבורspeech and מחשבה-thought. In his opening article for Chodesh Sivan, the B’nei Yissoschar writes: והנה ידוע דזאת התורה הניתנה למורשה מחויבים אנחנו לקיימה בכל חלקי מצותיה... כציצית, המעשה הוא עשיית המצות בגשמיות עשיה ממש,במחשבה דבור ומעשה והנה חלק המעשה בלבד בזולת דבור ומחשבה נקרא רק בחינת,ותפילין ולולב וכיוצא כמו העיבור בהתגלות וחידוש ראשון שיצא מן הכח אל הפועל להתהוות עיבור,עיבור עצמים בבטן המלאה אין לו בחינת דבור כי הפה סתום [נדה ל ב] (ומכל שכן שלא יצוייר בו וחלק הדבור בהצטרפו, רק מעשה יש לו כי יש לו תנועה באיבריו גם במעי אמו,)מחשבה That is the interpretation offered by Encyclopedia Talmudit Volume 2, footnote 5 in the entry of אמירה לגבוה כמסירה להדיוט. 12 The Sefer Avnei Miluim Siman 1/s’if koton 2 says that the principle of אמירה לגבוה כמסירה להדיוטis valid for a non-Jew too! 13 עם המעשה נקרא בחינת יניקה כמו הילד אחר השתלמות ימי העיבור נפתח פה הסתום ובהצטרף לדבור ומעשה גם חלק,'ועל ידי היניקה מעט מעט מתחיל לדבר והוא חידוש ב המחשבה זה נקרא מוחין כמו התינוק הגם שמתחיל לדבר עם כל זה אינו יודע לישא וליתן .'ולשאול ולהשיב כהוגן עד שישתלמו מוחותיו בגדלות והוא חידוש ג 'והנה הוא הרמז לכל אדם בכל עת ובכל זמן לא ישתלם בקבלת התורה עד יושלמו בו ג .חידושים הללו מחשבה דבור ומעשה It is known that we are required to fulfill the Torah that was given to us as a legacy, with all parts of its Mitzvos, in thought, in speech and in deed. מעשה-deed is the doing of the Mitzvos with actual physicality, like Tzizis, Tefilin, lulav, etc. This aspect, deed alone, without speech or thought, is comparable to the aspect of the fetus. Just like the fetus, which is a chiddush in actualizing the potential [of father and mother to create a new life] to become a fetus with substance in the full stomach [of the mother] has no power of speech, because the mouth is shut14 (and certainly one cannot envision that it has thought, so מעשה-deed alone has bodily movement, even inside the mother. The aspect of speech, when he joins the deed, is referred to as the aspect of nursing, similar to the way in which a child [at birth] following pregnancy has his [previously] closed mouth opened and through nursing he gradually begins to speak, and this is the second chiddush. B’nei Yissochor refers us to Masseches Niddah (30 b) where we read: שתי אציליו על, ידיו על שתי צדעיו. לפנקס שמקופל ומונח- למה הולד דומה במעי אמו:דרש רבי שמלאי ואוכל ממה, ופיו סתום וטבורו פתוח, וראשו מונח לו בין ברכיו, וב' עקביו על ב' עגבותיו,ב' ארכובותיו - וכיון שיצא לאויר העולם. ואינו מוציא רעי שמא יהרוג את אמו, ושותה ממה שאמו שותה,שאמו אוכלת . שאלמלא כן אינו יכול לחיות אפילו שעה אחת,נפתח הסתום ונסתם הפתוח Rabi Simlai interpreted-a child inside the mother is like a folded tablet, lying in place. His hands are on his temples, his arms are resting on his legs, his heels are by his buttocks, and his head is [folded down] between his knees. His mouth his shut and his navel is open and he eats from that which is mother eats and he drinks from that which is mother drinks and he does not emit waste because he would perhaps kill his mother. When he is born, that which was closed, opens and that which was open, closes. Were that not so, he would be unable to live even one hour. 14 When the aspect of thought joins the aspects of deed and speech, this is called מוחין-‘minds’ just like the child who begins to speak but has no ability to discuss, or ask and answer properly, until his מוחיןreaches completion with maturity, and that is the third chiddush. Thus, in addition to the quantitative physical development of the child inside the womb and out, there is qualitative development as well. That qualitative development is not only the unique additional functioning of the already-existing aspects. That qualitative development is the introduction of new aspects of life that are able to bring the individual into full and complete functionality. If full and complete functionality is defined by realization of all three of these aspects, rising to דבור-speech and culminating with the full use of מחשבה, then this aspect of sanctification, הקדש, culminates the second and third aspects in which speech alone accomplishes15 that which deed is to do and finally, מחשבה alone culminates that which we may have thought could have been accomplished only by deed and/or speech. Now that we have seen that the process of sanctification empowers man, and lets speech and thought replace action, we must wonder in what way we can approach such levels16 when we do not have the Beis HaMikdosh17. Man still remains a physical being, and therefore, even with the superiority of speech and thought, those Mitzvos that require action are not exempted by speech or thought. One is commanded to put on Tefilin and to take Lulav and Esrog. Those Mitzvos cannot be fulfilled by speech and thought alone. One is commanded to read Megillas Esther. He will not fulfill that Mitzvah by just ‘thinking about it’. 15 In fact, there are major discussions beginning with Chazal and continuing to this day regarding הרהור כדבור-is thought equivalent to speech. In particular the focus is in regard to the recitation of Shema’, davening and learning Torah. The discussion begins in Masseches B’rachos 20 b. 16 In fact, a person can sanctify articles בזמן הזה, even in the absence of the Beis HaMikdosh and those articles would have full sanctity. However, the issues with 17 The Rama in Shulchan Aruch Yoreh Deah Siman 258/s’if 13 writes: אלא, חייב לקיים מחשבתו ואין צריך אמירה, אם חשב בלבו ליתן איזה דבר לצדקה:הגה והעיקר כסברא. אינו כלום, וי"א דאם לא הוציא בפיו.דאם אמר מחייבין אותו לקיים ). (ועיין בחושן המשפט סימן רי"ב,הראשונה Gloss of Ramah-if one thought in his heart to give something for charity, he is obligated to fulfill his thought and he is not required to say [something to obligate himself], but that which he says, we obligate him to fulfill. There are those who say that if he did not utter [his gift to tzedaka] it does not count for anything. The basic din is like the first opinion. (See Choshen Mishpot Siman 21218). That is, if an act of Tzedaka can be accomplished through thought alone, it too has the capacity to raise a person in a way similar to Hekdesh. Perhaps that is the meaning of the verse in Mishlei (Perek 14/Posuk 34): :צדקה תרומם גוי וחסד לאמים חטאת Tzedaka will raise a nation and kindness to the nations is a sin. Rashi explains: : ישראל- צדקה תרומם גוי Tzedaka will raise a nation-Israel : שהיו נוטלים מזה ונותנים לזה- וחסד לאומי' חטאת and kindness to the nations is a sin-The nations took from this one and gave to that one. In Masseches Bava Basra (10 b) we learn: guarding them against impurity and misuse are many and grave and thus this idea which may be true is far from practical or advised. The Shulchan Aruch there brings another aspect in which Hekdesh is more potent in Kinyan-power than non-Hedkesh. 18 לד) צדקה/ מהו שאמר הכתוב (משלי יד, בני: אמר להן רבן יוחנן בן זכאי לתלמידיו,תניא , אלו ישראל- צדקה תרומם גוי:תרומם גוי וחסד לאומים חטאת? נענה רבי אליעזר ואמר ...) ומי כעמך ישראל גוי אחד בארץ19כג/ (שמואל ב ז:דכתיב The Braisa teaches: Raban Yochanan ben Zakai said to his students-what is the meaning of the verse “Tzedaka will raise a nation and kindness to the nations is a sin”? Rabi Eliezer responded and said, “Tzedaka will raise a nation”-this refers to Israel about whom it says, “Who is like Your People Israel, a unique nation in the land”. Tzedaka for the Jewish People is not just an act of charity. It is not only an act of righteousness. Tzedaka raises the Jewish People. It raises the Jewish People to a state of uniqueness. What is that state of uniqueness? The commentators explain that uniqueness in relationship to Tzedaka. Perhaps, we can add an additional factor. Israel is unique because Tzedaka raises us to a level in which our speech and our thoughts are meaningful in a concrete way. The words that we say bind us; the thoughts that we think oblige us to fulfill them, at least in some of the pursuits in which we participate. We do not have the Beis HaMikdosh today but we do have Tzedaka. We are used to saying Vayikro Rabba Parshas Behar (34): יותר ממה שבעל הבית עושה עם העני העני עושה עם בעל הבית More than the homeowner does for the poor man20, the poor man does for the homeowner. The entire verse reads: ל'קים לפדות לו לעם ולשום לו שם ולעשות לכם הגדולה...ומי כעמך כישראל גוי אחד בארץ אשר הלכו א :ונראות לארצך מפני עמך אשר פדית לך ממצרים גוים ואלהיו Who is like Your People Israel, a unique nation in the land that G-d went to redeem them for Him to be a nation and to give it a name and to do for your greatness and awesomeness for your land before the people whom You redeemed for Yourself from Egypt, nations and its gods. 19 We understand, correctly, that G-d takes care of the poor and the individual who donates to the poor is a vehicle in G-d’s plan. Thus, the donor is merely a ‘middleman’. However, the poor individual who accepts the charity allows the donor to have a Mitzvah opportunity. Thus, the poor man has done more for the rich man than vice-versa. With this comparison of the empowerment of Tzedaka, we can understand a further benefit that the poor man provides for the wealthy man. The opportunity to participate in the act of Tzedaka raises the power of our speech and our thought. Rather than lacking physical substance, in the case of speech, and being abstract in the case of thought, the act of Tzedaka empowers both and makes them substantive and concrete, effective and competent. In this month of Adar we remember the Mitzvah of Shekalim (which was given special mention last week) and Matanos LoEvyonim of Purim. The Shekalim were collected to provide the public offerings, Korbonos Tzibbur for the coming year and Matanos LoEvyonim are given to assure that the happiness of Purim is not in the province of the ‘haves’ and outside the province of the ‘have-nots’21. We often find that the one who gives charity is referred to the homeowner and the poor man is on the outside. Thus in the first Mishnah in Masseches Shabbos we read: כיצד העני עומד בחוץ ובעל הבית בפנים. What is the case? The poor man stands outside and the homeowner is inside. Perhaps this is an ancient understanding of the poor being homeless? 20 Rambam writes in Hilchos Megillah vChanuka (Perek 2/Halachah 17): שאין שם שמחה גדולה,מוטב לאדם להרבות במתנות אביונים מלהרבות בסעודתו ובשלוח מנות לרעיו שהמשמח לב האמללים האלו דומה לשכינה,ומפוארה אלא לשמח לב עניים ויתומים ואלמנות וגרים ) כי כה אמר רם ונשא שכן עד וקדוש שמו מרום וקדוש אשכון ואת דכא ושפל רוח-טו/שנאמר (ישעיהו נז .להחיות רוח שפלים ולהחיות לב נדכאים It is preferable for a person to increase his gifts to the poor (on Purim) rather than increasing his festive meal of the mishlo’ach monos-presents of food that he sends to his peers. This is because there is no happiness greater and beautiful than to gladden the hearts of the poor, the orphans, widows and converts. One who gladdens the heart of these unfortunates is comparable to the Shechinah as it says, ‘So says He Who is elevated and lofty, Who dwells forever, His Name is holiness, ‘exalted and holy I Hashem will dwell and the oppressed and of lowly spirit to enliven the spirit of those who are low and to enliven the heart of the oppressed. 21 As we have seen Tzedaka and Hekdesh are the means in which we are empowered, making our speech and thoughts as real and concrete as our actions. In Masseches Beitza (15 b), Rashi writes: אדר לשון קיום וחוזק. The name Adar is an expression of vitality and power. The Gemara there derives this from the verse in Tehillim (Perek 93/Posuk 4):'מקלות מים רבים אדירים משברי ים אדיר במרום ה. Greater than the sounds of mighty multitudes of water, breakers on the sea, Hashem is more powerful in the heights. Could it be that this month of Adar which we inaugurated this week receives it name because it provides special empowerment? Adar is strength, but that strength is not brute force. That strength is to take those aspects of our repertoire to which we relate to as ‘less real’ and actualize their potential as a vital force that that endows us with the ability to realize our potential and make us the beneficiary of וצדקה מרומם גוי, to reach our uppermost heights as individuals and as a nation The classic commentary on Mishneh Torah, the Maggid Mishneh writes on this Halachah: דברי רבינו ראויין אליו. The words of Rambam are appropriate for him. He implies that this Halachah was written by Rambam without having an explicit source in Chazal and thus, only a Rambam could express these ideas in the fashion that he did. Perhaps, based on the point that we are developing, we can comment on the choice of Rambam’s words. He writes: מוטב לאדם. It is better for an Odom to be extravagant with Matanos LoEvyonim rather than with the Seuda and Mishloach Monos. We know that the Rambam is uniquely particular in his writing and that each and every word has a purpose. Why didn’t Rambam write מוטב להרבות, it is better to be extravagant-and omit the word ?אדםWe know that he is talking about people. Perhaps, the Rambam is hinting that a person is able to reach a fulfillment of אדם when he gives Tzedaka generously. The fulfillment of אדםis to reach a point where his speech and his thoughts are just as meaningful as are the actions that he undertakes. Shabbat Shalom Rabbi Pollock