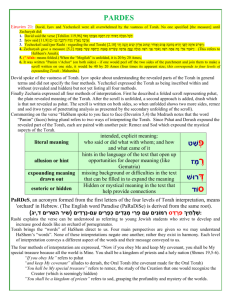

Mattan Torah

advertisement

פרשת משפטים The Torah is far more than grand pronouncements and miraculous events that grab the attention of the entire world. The purpose of the grand pronouncements and miraculous events at Mt. Sinai was not to make newspaper headlines. Its goal was to teach that G-d gives us the Torah and that He appointed Moshe Rabbenu has His unique emissary1. When that epochal time of Mattan Torah had passed, it was time to get down to the business of having the Torah belong to our everyday life. The fact that our ancestors understood that goal is evident in last week’s Parsha. We read (Sh’mos Perek 18/Posuk 13): :ויהי ממחרת וישב משה לשפט את העם ויעמד העם על משה מן הבקר עד הערב It was on the morrow, Moshe sat to judge the people and the people stood next to Moshe from morning until evening. What was that ‘morrow’? Rashi2 teaches us that it was the 11 Tishrei, in the second year3 of the Exodus. Of course the 11 Tishrei is always the day after Yom HaKippurim but in that year, it was more than ‘just’ the day following Yom HaKippurim. Yom HaKippurim that year was the conclusion of about 120 days following Mattan Torah and 80 days following the sin of the Eigel HaZahav. On that Yom 1 See Mishneh Torah LaRambam Hilchos Yesodei HaTorah Perek 8. See his commentary based on the Sifrei and his interpretation of it. Many commentators differ with Rashi for many reasons, not the least of which is the fact that the Torah writes this episode prior to writing about Mattan Torah. See Ramban, for example. 2 The first year of the Exodus began in Nissan, when we left Egypt. It concluded that Elul. The second year began in that Tishrei following the Exodus, some 6 ½ months later. 3 HaKippurim Israel received atonement for the grave sin of Eigel HaZahav because Moshe was allowed to bring the second ‘Ten Commandments Tablets’ to Israel4. It was the morrow of Yom HaKippurim in that second year following the Exodus that the entire Torah first became actualized for B’nei Yisroel. What happened on that very first day-all of Israel gathered to be with Moshe, overwhelming him, because they all wanted to learn Torah and apply it to their lives. That is the explanation that Moshe gave Yisro (P’sukim 16-17) when the latter queried regarding the ‘commotion’. כי יהיה להם דבר בא אלי ושפטתי:ל'קים...ויאמר משה לחתנו כי יבא אלי העם לדרש א :ל'קים ואת תורתיו...בין איש ובין רעהו והודעתי את חקי הא Moshe said to his father-in-law, because the people come to me to see G-d. When they have a matter, [the people] come to me and I judge between a person and his neighbor and I make known the statutes of G-d and His laws. Isn’t it remarkable? They had not yet begun to learn Torah. They did not know what was contained in Torah besides the Ten Commandments and the laws that were given in Marah and the laws of Pesach. Certainly their questions did not have specific references to specific Halachosthey were unaware of them. However, their thirst for the Word of G-d was so great that the masses converged upon Moshe Rabbenu asking him regarding the complete gamut of Torah law. With what body of laws does the Torah follow Mattan Torah? Mishpotim. The system of civil laws that regulate everyday activity is how the Torah follows Mattan Torah. The extraordinary is attached to the mundane. In fact, we note that the end of last week’s Parshas Yisro discusses the Mitzvah of the Mizbeach Adama-that which will be the outer altar in the Mishkan and in the Beis HaMikdosh and that subject is juxtaposed to Parshas Mishpotim. What is the reason for such a placement of two seemingly unrelated subjects? In fact, according to many opinions, Yom HaKippurim became “Yom HaKippurim” as a result of that initial and extraordinary atonement. 4 Rashi (Sh’mos Perek 21/Posuk 1) tells us that Chazal learned : לומר לך שתשים סנהדרין אצל המזבח,ולמה נסמכה פרשת דינין לפרשת מזבח Why was the section of laws placed next to the section of the altar? This is to tell you to place the Sanhedrin near the Mizbeach. Why was it necessary to place the Lishkas HaGozis, the ‘Hewn Chamber’ in the Beis HaMikdosh compound5? If the answer is that the Sanhedrin must be readily available to rule on the many questions that certainly arise in the Divine Service, it would be strange that that placement is learned in connection with dinnim? Certainly, the Sanhedrin did render many decisions, all of the time regarding that function. But, by learning this matter from dinnim seems to have a different implication. The subject of dinnim is not mundane. It belongs together with the altar because the proper instruction of dinnim is no less holy than the proper way to bring offerings. Just like the Kohen Godol belongs in the Beis HaMikdosh6, the Sanhedrin which adjudicates the ‘mundane’ is located within its perimeter as well. Although the chamber of the Sanhedrin was in that compound, it was not in the sanctified part of that compound. Thus, as long as a man was tahor, he could be within that chamber. 5 When the Kohen Godol suffers the loss of a member of his immediate family, he does not observe the laws of mourning as all others do. He cannot even attend their funeral. The Torah (Vayikro Perek 21/Posuk 12) expresses that point as: :'ל'קיו עליו אני ה...ל'קיו כי נזר שמן משחת א...ומן המקדש לא יצא ולא יחלל את מקדש א He may not leave the Sanctuary and he will not profane the Sanctuary of his G-d because the crown of the anointing oil of G-d is upon his head, I am Hashem. 6 Now, Chazal (Masseches Sanhedrin 19 a) teach us that the Kohen Godol is not physically imprisoned in the Beis HaMikdosh and that the intent of the verse is that he should not leave his state of holiness. However, there is an implication that the Kohen Godol is inextricably tied to the Mikdosh. The verses here, too, tie the Sanhedrin to that same location. Thus, when we approach the laws of our Parshas Mishpotim, we do so with the same sense of holiness as we would learn the laws of the Beis HaMikdosh and those who serve in it. What is a person’s obligation towards the property of the other? What is one’s responsibility? In the context of this question, the issue is not what is a person’s responsibility if he does damages? When does he pay, how does he pay and how much does he pay. In the context of this question, we want to know what is a person’s responsibility towards the property of the other so that damage will not occur? Many of the commentators7 cite a subject which is not in our Parsha has the basic source of this type of responsibility. In Parshas Ki Setze we learn the laws of השבת אבידה. A person has an obligation to return lost property to its rightful owner. The Torah writes in the concluding verse of that section (D’vorim Perek 22/Posuk 3): וכן תעשה לחמרו וכן תעשה לשמלתו וכן תעשה לכל אבדת אחיך אשר תאבד ממנו :ומצאתה לא תוכל להתעלם So shall you do for his donkey and so shall you do for his unique dress and so shall you do for all that is lost from your brother, that his lost from him, and you found it; you may not ignore. The damage that occurred at the loss of the article had nothing to do with me. Perhaps there were better reasons to explain the loss, a storm blew the article away, perhaps there were worse reasons-the owner was carrying the object inattentively and it dropped from his hand. I have no relationship to that monetary loss. See Kehilos Yaakov of the Steipler Gaon TZ”L, Masseches Bava Kamma Siman 1. This is his view and in a footnote he says that it was brought to his attention that such is the opinion of Rashash to Masseches Kesuvos 18 and the Chelkas Yoav, Choshen Mishpot Siman 20. 7 Despite my clear and complete lack of connection to the loss, when that object comes before me, the Torah obligates me to return it to the rightful owner. If I have difficulty in locating the rightful owner, the Torah (ibid. Posuk 2) makes the obligation clear: ואם לא קרוב אחיך אליך ולא ידעתו ואספתו אל תוך ביתך והיה עמך עד דרש אחיך אתו :והשבתו לו If our brother is not near you and you do not know who it is, you will take the article into your house and it will be with you until your brother seeks it and you shall return it to him. If such is my responsibility towards a loss to which I had no connection whatsoever, I am certainly obligated to take the proper care and not cause damage. The prohibition to cause damage is from the Torah. Such is the implication of Chazal in Masseches Gittin (53), the Vilna Gaon (Shulchan Aruch Choshen Mishpot 155) and others.8 The Mishnah (Masseches Bava Kamma Perek 1/Mishnah 2) explicates in greater detail the personal responsibility that we bear to the property of others. We read: כל שחבתי בשמירתו הכשרתי את נזקו הכשרתי במקצת נזקו חבתי בתשלומין כהכשר כל :וכשהזיק חב המזיק לשלם תשלומי נזק במיטב הארץ9...נזקו These phrases are cryptic so that after their translation we will focus on the explanation of some of them. The translation follows the commentary of Bartenura, with help from the expanded commentary of Mishnah Mevo’ores by Rav Kehati. I learned these sources in the Kehilos Yaakov (ibid.). There precise references are given and one can evaluate what is an explicit source and what is an implied source. 8 The parts of the Mishnah omitted here deal with definitions of property and ownership and the venue in which the damaging event occurred. 9 “For all that I am obligated to guard (to prevent it from causing damage), I have readied10 its damage11. If I readied partial damage on am obligated to pay as if I readied the entire damage12…When one damages, he is obligated the payment for the damages from his best land13.” We have translated הכשרתיas ‘readied’. In this and other contexts, הכשרrefers to a preparatory state. That is, in the explanation of Bartenura (in the following note) if the responsible individual acted irresponsibly, but no damage occurred, then there is no payment because there was no damage. Since there was a potential for damage and the responsible person brought about the situation in which that potential was created, he ‘readied’ it. 10 Bartenura writes: . ואני חייב עליו, אני הוא שהכשרתי וזמנתי אותו היזק, אם לא שמרתיו כראוי והזיק- הכשרתי את נזקו : שעליו היה מוטל שמירת שורו והרי לא שמרו כראוי לו,כגון המוסר שורו לחרש שוטה וקטן חייב I readied its damage-if I did not watch it appropriately and it damage, it is I who readied and ‘summoned’ that damage and I am obligated [to pay] for it. for example, [A person agreed to watch someone’s ox] and he transferred it to an [objectively] incompetent person [deaf-mute/ a fool or a child] I am obligated [to pay if damage occurred]. Upon him was the obligation to watch the ox and he did not watch it properly. 11 Bartenura writes: , ואם תקנתי וזמנתי מקצת הנזק אף על פי שלא זמנתי ותקנתי את כולו- 'הכשרתי במקצת נזקו וכו ונפל, כגון החופר בור תשעה ברשות הרבים ובא אחר והשלימו לעשרה.נתחייבתי עליו כאילו זמנתיו כולו כיון, כאילו עשה כל הנזק, אף על פי שלא תקן אלא מקצת הנזק. האחרון חייב,שמה שור או חמור ומת :דבתשעה ליכא מיתה I readied partial damage-If I developed (?) and summoned partial damage, even though I did not summon and develop all of it, I have become obligated for it as if I summoned it all. for example, one digs a pit 9 tefachim deep on public property and a second person digs [one tefach deeper) to a depth of 10 tefachim, and an ox or donkey fall there and die, the latter person is obligated to pay-even though he developed only part of the damage. It is as if he developed the entire damage, since [at a depth] of 9 tefachim the animal would not have died. 12 Chazal had a Massorah that only a 10 tefach deep pit would be fatal for a falling animal. Thus, the one who dug only 1 tefach made a qualitative change-the injurious pit not became fatal. One who damages is obligated to pay for damages. The default case is when a person pays money. When a person does not have cash to pay, but is a land-owner, Beis Din will collect the amount owed from his real estate. 13 Analysis of this Mishnah leads us to consider the perennial question of .14 ל'קיך שאל מעמך...ועתה ישראל מה ה' א If a person has more than one piece of landed-property, it is likely that the quality varies between one piece of land and another. The variance is due to the productive capacity of the property. עידית, the best property, produces an income on a smaller section; בינונית-middle grade, produces that income on a larger piece and זיבורית requires a much bigger piece of property to produce the same income as do the smaller fields of עידיתand בינונית. In such a case, there may be a dispute between the damager and the damagee. The damager, as long as he has to ‘unload’ property may wish to pay the damages from his lowest – grade property. He would rather rid himself of a labor-intensive piece of property and keep the better sections that produce the same income on smaller pieces and thus require less labor. The damagee wishes to have the best property. He claims that he should not have to have a lesser – quality piece of land that will be labor intensive and require him to put him in special effort to reclaim the money owed to him. If he cannot have cash, he demands, let him at least have a piece of property that will allow him to recover his money in the easiest way possible. What is the decision? In this week’s Parsha (Sh’mos Perek 22/Posuk 2) we read, :כי יבער איש שדה או כרם ושלח את בעירה בעירו ובער בשדה אחר מיטב שדהו ומיטב כרמו ישלם When a person’s animal destroys another’s field or vineyard and he sends his animal and destroys the field of another, the best of his field and the best of his vineyard he shall pay. Thus, the Torah gives a clear ruling. The damagee is entitled to receive the highest grade of property in an instance when the damager is unable to pay cash for the damage that he caused. This is a fragment of the Posuk in Parshas Eikev (D’vorim Perek 10/12). In its entirety it reads: ל'קיך ללכת בכל דרכיו ולאהבה אתו...ל'קיך שאל מעמך כי אם ליראה את ה' א...ועתה ישראל מה ה' א :ל'קיך בכל לבבך ובכל נפשך...ולעבד את ה' א And now, Israel, what does Hashem your G-d ask from you? Only to fear Hashem your G-d, to go in all of His ways and to love Him and to serve Hashem your G-d with all of your heart and with all of your life. 14 In Masseches B’rachos (33 b), the Gemara expresses astonishment at the words, ‘only’ to fear G-d. the Gemara writes: ?אטו יראת שמים מילתא זוטרתא היא Is the fear of heaven a small matter [that it is appropriate to refer to it as ‘only’]? The Gemara answers: לגבי משה מילתא זוטרתא היא,אין. Yes, in regards to Moshe it was a small matter. This answer seems to be unsatisfactory on two levels. The first level, more shallow, is to question the fact that Moshe Rabbenu compares us to him. [This verse was said by Moshe Rabbenu, as is the norm throughout Sefer D’vorim.] How can we be expected to be on the level of Moshe Rabbenu? [Of course, one could answer, and it would be correct, that here we see another sterling example of the incomparable humility of Moshe Rabbenu.] A second question, more profound, is in regards to Moshe himself. It is obvious that those issues which test others were not of consequence to Moshe Rabbenu. The issues and challenges of ‘common folk’ were not in any way a test for Moshe. He was above them. On the other hand, can we say that Moshe Rabbenu did not have his own challenges, based on the unique level where he was? At the end of the Torah (D’vorim Perek 34/Posuk 17) we read: :ומשה בן מאה ועשרים שנה במתו לא כהתה עינו ולא נס לחה Moshe was 120 years old at his death; his eye did not dim, and his face had not changed (=aged. This is according to the translation of Onklos. The literal meaning of this last phrase is “his fluid did not escape him”.) It would seem that this description of Moshe Rabbenu’s physical state of health, at the age of 120 he had the prowess, stamina and appearance of a young man, should not be his eulogy. Were Moshe to have been near-sighted, with dried-out skin and using a cane to walk-would he not still be Moshe Rabbenu? Would we have thought less of him he would have had to talk louder for him to hear us because at his age this hearing ability had lessened? It is true that none of the above indications of old-age appeared on him, but what is the need for such a tribute to the vitality of his physical being? The answer seems to be that the Torah is telling us that Moshe Rabbenu was striving to improve himself on that 7th of Adar, over 3200 years ago. His eyes that looked forward to new accomplishments were as vigorous as ever and his spiritual determination was as fresh as that of a young man. Rabi Tzadok HaKohen seems to make this point when he writes in Tzikdas HaTzaddik (141): לא כהתה עינו וגו' שלא היה לו למעלותיו שום הפסק. What does G-d want from us? What are the responsibilities that are incumbent upon us as is expressed by this Mishnah, and by the entire body of law dealing with damages. There are many instances in which a person does direct physical harm or property damage and it is apparent that he is responsible to make restitution. If he strikes another person or drives his car into the automobile of someone else, he should certainly have to pay. He has done a direct action of damage for which the Torah. However, such is not the case of the Mishnah. In the case of the Mishnah, he has only ‘readied’ damage. We do not know if the incompetent shomrim will be incompetent in the particular situation in which we find them. We do not know that something will happen to the deposited article that will cause it to be damaged or ruined. We do not know that an animal will fall into this pit, which now has been enlarged by only one tefach. In fact, it is quite possible that the deposited article will be is as good shape when the owner comes to reclaim it as it was when he gave it over to the watchman. Certainly there are many other factors involved before the damage will occur and the person whom the Mishnah holds responsible is far removed from those factors. The expression of ‘readied’ is most appropriate. Why should he be held responsible as a damager when he did no more than ready the damage? In a seminal investigation regarding property damage, with particular attention to a comparative study of damages inflicted by one’s animal and damages inflicted by a fire lit by a person on his own property, without any intention for arson, Rav His eye did not dim-there was never any interruption in the ascent of Moshe Rabbenu to his highest levels. Thus, it could be that the מילתא זוטרתא, the ‘small matter’ was not said in regards to the challenge of Man to fulfill his obligation towards Yiras Shomayim. Rather, that it was a small thing for G-d to request from us in light of the bounty that we receive from Him always. Yaakov Yechiel Weinberg15 points to the issues by which the Halachah tells us that one is culpable for inflicted property damage. He summarizes his understanding of the basis of Halachic monetary culpability with the following: או,לא הבעלות כשהיא לעצמה גורמת חיובים אלא העמידה ברשותו וחובת השמירה . מנקודת השקפה זו אין הבדל בין אש ובין שור.הזנחתה של חובה זו גורמת חיובים שהרי גם. כך חייב באשו, וכשם שהוא חייב בנזקי שורו.בשניהם חלה חובת השמירה . מה שנעשה בידיו הוא ברשותו. שהרי הוא הביאו לעולם,האש הוא ברשותו Ownership alone does not cause financial culpability-rather the fact that the article that inflicts damage in under the supervision of the individual as well as an obligation to care for the object [that it should not cause harm]. Otherwise, the neglect of those responsibilities causes culpability. From this standpoint, there is no difference between [the damages caused by one’s] fire16 or one’s ox. For both, there is a requirement for supervision. Just like he pays for the damage inflicted by the ox, so he must pay for the damage inflicted by his fire. The fire was in his possession; he brought it into existence. That which is made by a person is in his control [and thus he is responsible for it]. This article is based on Mechkar 5 that appears in the 4 volume edition of Sridei Eish, volume 4, pages 124-132. 15 It also appears in the collection of his essays arranged according to the Gemaros upon which they were based. This is Siman 26 to Masseches Bava Kamma. The editor of this collection is Rav Avraham Abba Weingort Shlita who taught in Michlalah for many years, including some short stints in Machal. Some of the readers may have had the z’chus to been his students in his class on Parshas B’har. It would seem more likely to obligate payments for fire damage. The fire did not exist until the person lit it. On the other hand, the existence of the damaging ox did not come about because of the culpable individual. Its existence is independent of him. On the other hand, the ox is his property. He bought it and owns it like any other piece of tangible property that exists. Fire, not being tangible, is not ‘owned’ by the one who lit it. Thus, there is a place to say that a fire that was lit on Reuven’s property and accidentally spreads to that of Shimon, should not be Reuven’s responsibility. The definition given here refutes such a claim. 16 Even though causation17 is an essential factor in determining culpability for damage, responsibility seems to be equally as essential, if not even more significant. Where does responsibility end? When can a person say ‘that is not my problem-I am no longer involved’? This Mishnah seems to give a most restrictive definition to personal responsibility, at least vis a vis damaging the property of the other. A person cannot walk away from responsibility. A person who has invoked a particular situation remains responsible for that situation until it no longer exists. If one gives an article for which he was entrusted to safeguard to an incompetent person, he remains responsible18 for that article until he resumes his personal safeguarding or returns the article to its owner. We may wish to say he only ‘readied’ the damage, he set into motion circumstances that would allow the damage to occur, but he did not really do it. The Halachah denies such a claim. In this instance, ‘readying’ is equivalent to performing the damage directly. In reference to the laws of damages, we have three terms: מעשה-direct action, גרמי (garmi) semi-direct causation, ( גרמאge’ro’moh) –indirect causation. 17 The basic principle is that an individual is culpable for damages done by מעשהand גרמיand not culpable to be required to pay for damages done by גרמא. For a comprehensive treatment of this subject see Encyclopedia Talmudit, volume 6: גרמא בנזיקין; גרמי. The Shomer himself certainly has obligations, as told to us in this week’s Parsha. For example, if he receives wages for watching the article, he must pay if he is negligent, or the article is lost or stolen. When he gives the article to this incompetent watchman, that is an act of negligence and thus whatever will occur is the appointed watchman’s responsibility. This is true even if there is an unpreventable accident for which the watchman would not have been culpable were the article to have remained under his care. 18 If one comes across a pit in a public place19 and adds to it one tefach of depth, he is culpable. The pit was already there. Not only was the pit there, it was already capable of damaging the animal that would fall into it. The one who originally dug it no longer bears responsibility when the new person comes and extends its depth from 9 tefachim to 10. This new person only added to the ‘readiness’ of the pit to be harmful. Why should that ‘readying’ be culpable? The answer, again, is this is the responsibility that the Torah puts upon us. The Sanhedrin resides within the perimeter of the Beis HaMikdosh and the Torah teaches us property laws immediately after presenting us with the Ten Commandments. Two juxtapositions are placed before us in order that the message of the Torah be understood. Man’s role in this world is not to seek to escape responsibility. Man’s role in this world is not to abdicate. Man’s role in this world is to seek responsibility and to measure up to its requirements as successful as he can. That is what G-d asks from us. Our vitality must remain fresh and our eyes open always. Whether we can be as great as Moshe Rabbenu is an issue that may be open for discussion20. But our ability to have dynamism in our life is not. responsibly. Everyone begins with equal opportunities. Everyone can accept If ownership is one of the requirements for culpability-one may ask, ‘who owns a pit on public property?’ 19 The answer was already asked and given in Masseches Pesachim (6 a): א"ר אלעזר שני דברים אינן ברשותו של אדם ועשאן הכתוב כאילו ברשותו ואלו הן בור ברה"ר וחמץ .משש שעות ולמעלה Rabi Eliezer said, two items are not in a person’s possession, but the Torah made it as if they were. They are: a pit in a public place and chometz [from Erev Pesach] at midday. See Rambam Hilchos Teshuva Perek 5/Halachah 2 who writes: .כל אדם ראוי לו להיות צדיק כמשה רבינו Every person is capable of being a Tzaddik like Moshe Rabbenu! 20 That idea of equal opportunity is expressed this Shabbos Parshas Shekolim when we read about the communal obligation for the purchase of the annual set of public Korbonos. We read (Sh’mos Perek 30/Posuk 15): :העשיר לא ירבה והדל לא ימעיט ממחצית השקל לתת את תרומת ה' לכפר על נפשתיכם The wealthy person cannot give more and the poor person cannot give less than one-half shekel, a donation of Hashem to atone for your souls. Accepting responsibility means participation. That participation is not competitive. In such a grave area as the atonement brought about through Korbonos, are all equal. But if one absences himself and shirks responsibility, then there can be no atonement because there was no responsibility. As we saw, the starting point for the Mitzvah-content of these laws of damages is that of השבת אבידה. Let us look again at that verse that we saw earlier: וכן תעשה לחמרו וכן תעשה לשמלתו וכן תעשה לכל אבדת אחיך אשר תאבד ממנו :ומצאתה לא תוכל להתעלם So shall you do for his donkey and so shall you do for his unique dress and so shall you do for all that is lost from your brother, that his lost from him, and you found it; you may not ignore. You may not ignore; you may not make yourself invisible. You may not hide. A responsible person is a participant. A responsible person participates in the process of bringing the redemption. In the month of Adar which we welcome in these next days we have the specific Geula of Purim. We pray for that Geula to bring us to the all-encompassing Geula bim’heira b’yo’meinu. Shabbat Shalom Chodesh Tov Rabbi Pollock