Research Questions

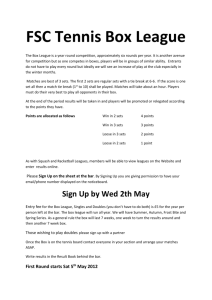

advertisement