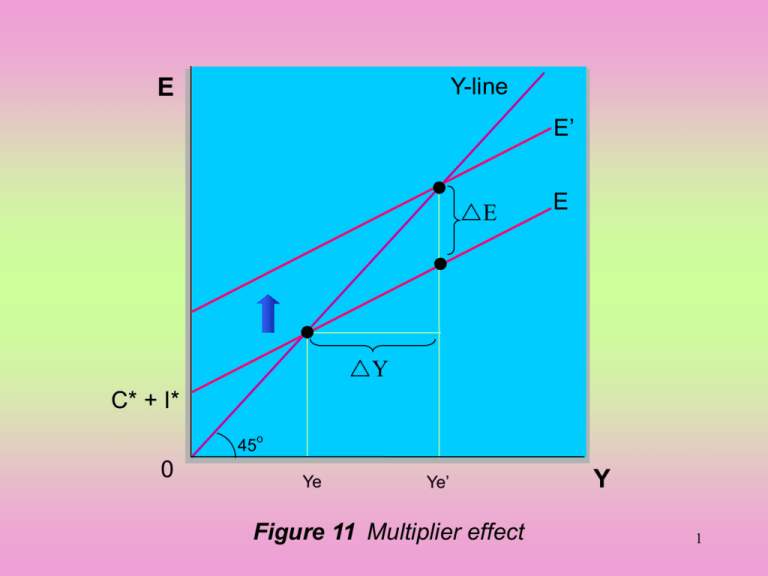

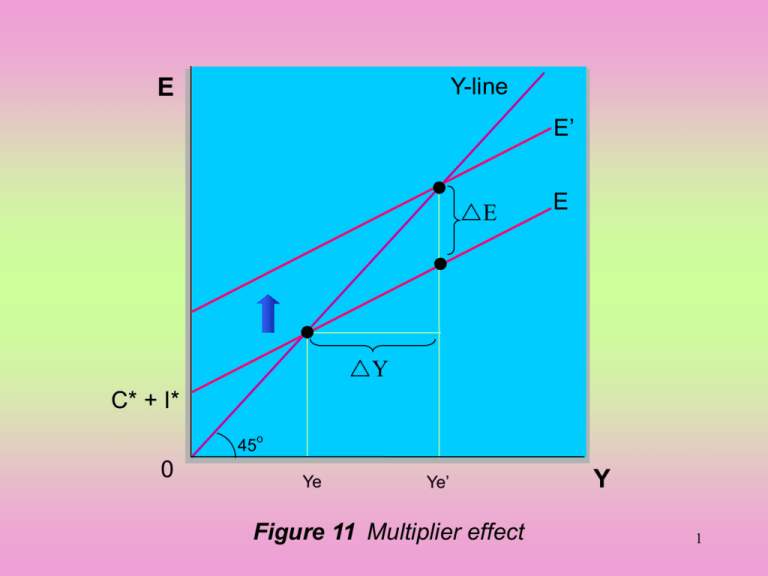

Y-line

E

E’

rE

E

rY

C* + I*

45

0

o

Ye

Ye’

Figure 11 Multiplier effect

Y

1

Aggregate expenditure

(trillions of 1992 dollars)

The Multiplier

(Parkin)

o

45 line

9

8

7

6

5

0

e

c'

b'

a'

6

d

c

b

a

5

e' AE0

d'

A $0.5 trillion

increase in

investment...

AE1

…increases

real GDP by

$2 trillion

7

8

9

Real GDP (trillions of 1992 dollars)

2

The

Multiplier

Process

(Parkin)

2.0

1.5

1.0

0.5

0

1 2 3 4 5 6

Expenditure round

7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

Increase in current round

3

Cumulative increase from previous rounds

Advanced

Advanced Level

Level

Macroeconomics

Microeconomics

Dr. Lam Pun Lee

Y-line

E

E’

E

45

0

o

Ye

Y1 Y2 Ye’

Y

Figure 14 The movement of expenditure multiplier 4

Previous

slide

1. Calculate the equilibrium level of income.

AE = C + I

AE = 40 + 0.75Y

AE = Y in equilibrium

40 + 0.75Y = Y

Y = 160

2. If I is increased by 10, calculate the new equilibrium

level of income.

AE = C + I = 50 + 0.75Y

AE = Y in equilibrium

50 + 0.75Y = Y

Y = 200

5

An autonomous change in

investment by 10 induces a larger change (40)

in equilibrium level of income.

Why is this so?

6

Rounds of

effects

Autonomous Induced change

change in I

in C

Change in Y

1st

$10

-

$10

2nd

-

$7.5

$7.5

3rd

-

$5.625

$5.625

4th

-

$4.21875

$4.21875

…

-

...

...

Total change:

$10

$30

$40

7

The Multiplier Process

(Miller)

Assumption: MPC = .8 or 4/5

Round

1 ($100 billion per

year increase in I)

2

3

4

5

.

.

.

All later rounds

Totals

Annual Increase

in Real

National Income

($ billions per year)

Annual Increase

in Planned

Consumption

($ billions per year)

Annual Increase

in Planned

Saving

($ billions per year)

100.00

80.00

64.00

51.20

40.96

.

.

.

163.84

80.000

64.00

51.200

40.960

32.768

.

.

.

131.072

20.000

16.000

12.800

10.240

8.192

.

.

.

32.768

500.00

400.00

100.0008

Slide 12-62

How does the Multiplier

work (P.13-7.2.2.2.)?

Any initial change in

spending by the government,

households, or firms creates

a chain reaction of further

spending

9

Y = $10 + $7.5 + $5.625 + …

= I + C + C + …

= I + cY + c2Y + …

= I + cI + c2I + …

= I (1 + c + c2 + …)

= I [1/(1-c)]

Multiplier (k) = Y / I = 1/(1-c)

10

One divided by one tenth equals

10

MULTIPLIER

.

1 .

1

X

1

10

10 =

1

=

10

11

If investment increases by $100,

with an MPC of 9/10, what effect

will this have on the economy?

The economy will grow by

$1,000 eventually

12

If investment declines by $100,

what’s the effect on the economy

with an MPC of 9/10?

The economy will shrink by

$1,000

13

Numerical example

I = 10

c = 0.75

k = 1/(1-c) = 4

E

Y = k I = 4*10 = 40

45 line

E = 50 + 0.75Y

E = 40 + 0.75Y

0

160 200

Y

14

Given:

C = 20 + 0.75Y

I = 20 + 0.1Y

1. Calculate the change in Y resulted from an

autonomous increase in I by $10.

2. Calculate the value of the multiplier.

15

1. Calculate the change in Y resulted from an

autonomous increase in I by $10.

When I = 20 + 0.1Y,

AE = C + I

When I = 30 + 0.1Y,

AE = C + I

AE = 40 + 0.85Y

AE = 50 + 0.85Y

AE = Y in equilibrium

AE = Y in equilibrium

40 + 0.85Y = Y

50 + 0.85Y = Y

Y = 266.67

Y = 333.33

Change in Y = 66.67

16

2. Calculate the value of the multiplier.

k = Change in Y / Change in I = 6.67

If I is an induced function, the size

of the simple Keynesian multiplier

will be greater. Why is this so?

17

Multiplier with induced I

1/mps-mpi

18

Figure 23-10 (Lipsey)

The Size of the Simple Multiplier

19

Relationship between MPC, MPS, and

the Spending Multiplier

MPS

Spending

Multiplier

.90

.80

.75

.67

.10

.20

.25

.33

10

5

4

3

.50

.33

.50

.67

2

1.5

MPC

20

E

S

S’

A

C

I

B

0

Y

Figure 12 The multiplier effects of autonomous

decrease in saving (= C rise)

21

E

S

I’

B

A

C

I

0

Y

Figure 13 The multiplier effects of autonomous

increase in investment

22

3-Sector & 4-Sector Models

The simple Keynesian model discussed

is a two-sector model, which includes

only firms and households. In this

section, we first add the government

sector and then the foreign trade sector

into our model. Lastly, we consider the

concepts of aggregate demand and

aggregate supply and how they are

related with the Keynesian model.

23

Next

slide

C

Household

S

Financial markets

Income

generated

Y

National expenditure

I

Government

T

National income

G

E

Firms

Payment for goods

and service

Figure 1 Three-sector national income model

24

The circular flow of income

Investment (I)

Factor

payments

Consumption of

domestically

produced goods

and services (Cd)

Government

expenditure (G)

BANKS, etc

GOV.

Net

Net

taxes (T)

saving (S)

25

E

Slope = c (1 – t)

C

a-cT*

0

Y

Figure 2(d) Consumption function in an 3-sector

income-expenditure diagram

26

Keynes and the Great Depression

• Keynes argued that prices and wages are not

sufficiently flexible to ensure the full employment

of resources

• Furthermore, Keynes argued that when resources

(especially labor) are not fully employed (due to a

lack of private investment expenditures), the

government could provide offsetting expenditures

as a means of stabilizing the economy

• Thus, Keynesian economics places emphasis on

planned expenditures and all its components

27

What is the GDP Gap (P.167.2.5.4. & Wong 2000: 104)?

The difference between

full employment real

GDP and actual real GDP

28

What is the Recessionary

AD Gap (P.16-7.2.5.4.)?

The amount by which

aggregate expenditures

fall short of the amount

required to achieve full

employment equilibrium

29

E

Y-line

G

E

DG

R

45

0

o

Ye

Yf

Y

Figure 2(a) Deflationary AD gap

30

W, J

The deflationary AD gap

W

J

O

Ye

Y

31

W, J

The deflationary AD gap

W

J

O

Ye

YF

Y

32

W, J

The deflationary AD gap

Deflationary AD gap

W

c

d

O

Ye

YF

J

Y

33

W, J

The deflationary AD gap

Deflationary AD gap

W

c

d

O

Ye

YF

J*

J

Y

34

What is the Keynesian

remedy for a Recessionary

AD Gap (P.16-7.2.5.5.)?

Increase autonomous

spending by the amount

of the recessionary AD

gap

35

What can the

Government do to close a

Recessionary AD Gap?

• Increase government

spending

• Lower taxes

• Raise transfer payments

36

Exhibit 2: U.S. Federal Budget Deficits

and Surplus Relative to GDP (P.17-7.2.6.1.2.)

1

1970

1975

1980

1985

1990

1995

2000

0

Percent of GDP

–1

–2

–3

–4

–5

–6

–7

Fiscal Year

Federal Budgets and Public Policy

Source: Developed based on budget figures in Economic Report of37

the President, February 1999.

3

What is an Inflationary AD

Gap (P.16-7.2.5.4.)?

The amount by which

aggregate expenditures

exceed the amount

required to achieve full

employment equilibrium

38

E

Y-line

E

F

IG

45

0

G

o

Ye

Yf

Y

Figure 2(b) Inflationary AD gap

39

W, J

The inflationary AD gap

W

J

O

Ye

Y

40

W, J

The inflationary AD gap

W

J

O

YF

Ye

Y

41

W, J

The inflationary AD gap

Inflationary AD gap

W

g

J

h

O

YF

Ye

Y

42

W, J

The inflationary AD gap

Inflationary AD gap

W

g

J

J*

h

O

YF

Ye

Y

43

What is the Keynesian

remedy for an Inflationary

AD Gap (P.16-7.2.5.5.)?

Reduce autonomous

spending by the amount

of the inflationary AD gap

44

How can the Government close

an Inflationary AD Gap?

• Cut government spending

• Increase taxes

• Reduce transfer payments

45

9. Keynes’ criticism of the classical theory was

that the Great Depression would not correct

itself. The multiplier effect would restore an

economy to full employment if

a. government would follow a “least

government is the best government”

policy.

b. government taxes were increased.

c. government spending were increased.

d. government spending were decreased.

c. Keynes’ prescription to cure the Great

Depression was for government to play an

active role rather than depend on the

classical theory that the price system will

46

eventually restore full employment.

10. The equilibrium level of real GDP is $1,000

billion, the full employment level of real

GDP is $1,250 billion, and the marginal

propensity to consume (MPC) is 0.60. The

full-employment target can be reached if

government spending is increased

a. by $60 billion.

b. by $100 billion.

c. by $250 billion.

d. by $25 billion.

b. Change in real GDP required = spending

multiplier x change in government spending

(G). Rewritten,

G = 1/(1 - 0.60) x ($1,250 - $1,000)

G x 2.5 = $250

47

G = $100 billion.

E

Y-line

E

45

0

o

Yf = Ye

Y

Figure 2(c) Equilibrium income equals

potential income

48

Does the equilibrium yield full

employment?

Not necessarily, according to

Keynes. We could move toward

a less than full employment

equilibrium.

49

What can we do if the

economy is moving toward

less than full employment?

We use our fiscal policies

to shift the equilibrium to

a point of GDP that gives

us full employment.

50

What is Fiscal Policy? (P.16-7.2.6. & Wong

2000: 137)

• Fiscal policy is the deliberate

manipulation of government

purchases, transfer payments, taxes,

and borrowing in order to influence

macroeconomic variables such as

employment, the price level, and

the level of GDP

51

What is a Discretionary

Fiscal Policy (P.16-7.2.6.1. & Wong 2000: 139)?

The deliberate use of changes

in government spending,

transfer payments, taxes and

borrowing to alter aggregate

demand and stabilize the

economy

52

Discretionary Fiscal Policy

(P.16-7.2.6.1. & Wong 2000: 139)

= The discretionary changes in

government expenditures and/or

taxes in order to achieve certain

national economic goals

Slide 13-8

• High employment

• Price stability

• Economic growth

• Level of GDP

• Improvement of international payments

53

balance

Why is Government spending

considered an Autonomous

Expenditure (Wong 2000: 94)?

Because Government

spending is primarily the

result of a political

decision made

independent of the level

of national output.

54

What are examples of

Expansionary Fiscal Policy

(P.16-7.2.6.1.1.)?

• Increase government

spending

• Decrease taxes

• increase government

spending and taxes equally

55

The Effect on GDP of an Increase in

Government Spending

$

45o

C+I+G’

C+I+G

G

Simple government expenditures multiplier =

GDP/G = 1/(1-MPC)

GDP

Real GDP

56

The Effect on GDP of a Decrease

in Lump-sum Taxes

$

45o

C’+I+G

C+I+G

Simple tax multiplier =

GDP/T = -MPC/(1-MPC)

GDP

Real GDP

57

Planned Spending

Shifting the aggregate demand curve

upward

C2 + I2 + G2

C1 + I1 + G1

less than full employment

full employment

45o

Real GDP

58

How can we shift the aggregate

demand curve upward?

We can use fiscal policies to

• lower taxes

• increase government

spending

59

E

Y-line

E’

E

45

0

o

Ye

Yf

Y

Figure 3(a) Expansionary fiscal policy

60

What is a Cyclical Deficit & a

Structural Deficit (P.16-7.2.6.1.4.)?

• The part of the deficit that

varies with the business cycle

is a Cyclical Deficit.

• The part of the deficit that is

independent of the business

cycle is a Structural Deficit.

C:\My Documents\Econppt\Macro\HLch27GovtSpending.ppt

61

What are examples of

Contractionary Fiscal Policy

(P.16-7.2.6.1.1.)?

• Decrease government

spending

• Increase taxes

62

E

Y-line

E

E’

45

0

o

Yf

Ye

Y

Figure 3(b) Contractionary fiscal policy

63

E

Y-line

c rT*

C+I+G

rG*

45

0

Figure 4

o

Y

rY

A balance-budget increase in G and T will have

an expansionary effect on the economy

64

What is the Tax Multiplier

(P.15-7.2.4.3.=Wong 2000: 101)?

The change in aggregate

demand (total spending)

resulting from an initial

change in taxes

65

What is the Balanced

Budget Multiplier (P.157.2.4.3.)?

An equal change in

government spending and

taxes, which changes

aggregate demand by the

amount of the change in

government spending

66

What is a Countercyclical

Fiscal Policy (P.16-7.2.6.1.3.)?

Changes in taxes or

government spending

designed to counteract a

boom or recession.

C:\My Documents\Econppt\Macro\HLch27GovtSpending.ppt

67

What are limitations to

Countercyclical Policies?

Timing Problems – there are

the lags of recognition,

decision, and action

Irreversibility – government

policies tend to become

entrenched

68

Fiscal Policy: problems

• Time lags (P.18-7.2.6.3.1.)

– Recognition Time Lag

• The time required to gather information about the

current state of the economy

– Action Time Lag

• The time required between recognizing an economic

problem and putting policy into effect

– Particularly long for fiscal policy

– Effect Time Lag

• The time it takes for a fiscal policy to affect the

economy

69

Slide 13-39

Discretionary Fiscal Policy

in Practice

• Fiscal policy time lags are long.

A policy designed to correct a

recession may not produce results

until the economy is experiencing

inflation.

• Fiscal policy time lags are variable

in length (1–3 years). The timing of

the desired effect cannot be predicted.

Slide 13-42

70

What are Automatic Stabilizers?

(P.17-7.2.6.2. & Wong 2000: 138)

Forces that reduce the size

of the expenditure

multiplier and diminish the

impact of spending shocks

71

What is an Automatic

Stabilizer (P.17-7.2.6.2. & Wong 2000: 138)?

• Government expenditures and tax

revenues that automatically change

levels in order to stabilize an

economic expansion or contraction

• Structural features of government

spending and taxation that smooth

fluctuations in disposable income

over the business cycle

72

Automatic Stabilizers

• Changes in government spending and

taxation that occur automatically without

deliberate action of government

• Examples:

–Progressive income tax system with its

increasing marginal income tax rates

–Unemployment compensation

–Welfare spending

–Transfer payments

73

Slide 13-43

What are some examples of

Stabilizers?

• Transfer payments that increase and

decrease with changes in the economy

• Income (proportional/progressive) taxes

that rise and fall with income

How do automatic stabilizers affect spending

shocks?

• They smooth out the ups and downs of the

economy.

74

Automatic Stabilizers

Government Transfers

and Tax Revenues

Unemployment

compensation and welfare

Tax

revenues

Budget surplus

Budget

deficit

The automatic changes tend

to drive the economy back

toward its full-employment

output level

0

Y2

Y1

Real GDP per Year

($ trillions)

Slide 13-44

75

Automatic Stabilizers

Government Transfers

and Tax Revenues

Unemployment

compensation and welfare

Tax

revenues

Budget surplus

Budget

deficit

0

Y2

Figure 13-6 Slide 13-45

Yf

Real GDP per Year

($ trillions)

Y1

76

C

Household

National income

S

National expenditure

Financial markets

I

Government

T

Foreign markets

G

X

Y

Income

generated

Firms

E

M

Payment for goods

and service

Figure 5 Four-sector national income model

77

The circular flow of income

INJECTIONS

Export

expenditure (X)

Investment (I)

Factor

payments

Consumption of

domestically

produced goods

and services (Cd)

Government

expenditure (G)

BANKS, etc

Net

saving (S)

GOV.

ABROAD

Import

Net

expenditure (M)

taxes (T)

WITHDRAWALS

78

E

Y-line

E = C + I + G + (X - M)

(a)

0

45

o

Y

Ye

E

S+T+M

(b)

I+G+X

0

Y

Figure 6 Determining the equilibrium

income of an open economy

Ye

79

P

AD

0

Q

Figure 7 Aggregate demand curve

80

P

AS

0

Qf

Q

Figure 8(a) Keynesian (kinked) aggregate supply

curve

81

P

AS

0

Qf

Q

Figure 8(b) Upward-sloping aggregate supply curve

82

P

AS

0

Qf

Q

Figure 8(c) Classical aggregate supply curve

83

P

AS

Pe

AD

0

Qe

Q

Figure 9 Equilibrium of aggregate demand

and supply

84

P

AS

Qf

0

DG

AD

Q

Figure 10(a) Unemployment equilibrium

85

P

AS

AD

Qf

0

IG

Q

Figure 10(b) Over-employment equilibrium

86

P

AS

AD

0

Qf

Q

Figure 10(c) Full employment equilibrium

87

Advanced

Advanced Level

Level

Macroeconomics

Microeconomics

(a) P

(b)

AS

•

•

P

AS

AD’

•

AD

0

If P

Q

Qf

•

AD’

AD

Q

0

If P unchanged

(c)

P

AS

Figure 11

Multiplier effect with

changing price level

•

•

0

Qf

AD’

AD

Q

88

Previous

slide

The paradox of thrift:

An attempt to save more may

lead to lower income and no

actual increase in saving if

everybody do the same.

Saving is a virtue for the

individual, but may not be good

for the society as a whole!

89

Case 1

When you want to save more by decreasing

autonomous consumption and others follow

what you did, the saving function shifts

upwards. The national income is decreased.

The level of saving remains the same.

S

S’ = -a’ + sY

S = -a + sY

I = I*

Ye’ Ye

Y

90

Case 2

If investment is an induced function, how will an

upward shift in saving function affect the level of

equilibrium income and saving? Show your answer

in the following diagram?

S

S’ = -a’ + sY

S = -a + sY

I = I* + iY

S

S’

Ye’

Ye

Y

91

Resolution:

The amount of investment is independent of the rate

of interest and the amount of saving. An increase in

saving leads to an accumulation of unintended

inventory and then output and income will fall.

Rate of interest (r)

D = investment

S = saving

S, I

S’

S

S’

I

Ye’

Loanable funds for investment

Ye

Y

92

Would the paradox still arise

if investment is negatively

related to the rate of interest?

93

Annual Percentage Changes in U.S. Real GDP,

Real Consumption, and Real Investment

30.0

Investment

20.0

15.0

GDP

10.0

Consumption

5.0

–10.0

1998

1996

1994

1992

1990

1988

1986

1984

1982

1980

1978

1976

1974

1972

1970

1968

1966

1964

–5.0

1962

0.0

1960

Annual percentage change

25.0

Year

–15.0

–20.0

Source: Based on annual estimated found in Survey of Current Business, U.S. Department of Commerce, 77 (August 1997)

and 79 (January 1999).

94

Why does the Consumption

Function Shift (P.20-7.3.1.1.)?

• Expectations

• Wealth

• Price level

• Interest rate

28

95

How do Expectations affect the

Consumption (P.22-7.3.1.1.10)?

Consumers expectations of

things to happen in the

future will affect their

spending decisions today

29

96

How does Wealth affect the

Consumption (P.20-7.3.1.1.5)?

Holding all other factors

constant, the more wealth

households accumulate,

the more they spend at

any current level of

disposable income

30

97

How does the Price Level

affect the Consumption

(P.21-7.3.1.1.6)?

Any change in the general

price level shifts the

consumption schedule by

reducing or enlarging the

consumers purchasing power

31

98

How does the Interest Rate

affect the Consumption

Function (P.21-7.3.1.1.8)?

A high interest rate will

discourage people from

borrowing money and a low

interest rate will encourage

people to borrow money

32

99

According to Keynes, what

determines the level of

Investment?

Expectations of future

profits is the primary

factor, the interest rate is

the financing cost of any

investment proposal

36

101

7.4.3. How do Expectations

affect Investment?

Business people are quite

susceptible to moods of

optimism and pessimism

41

102

How do Business Taxes

affect Investment?

Business decisions

depend on the expected

after-tax rate of profit

45

106

Can the government maintain a

permanent budget deficit? What would

you need to know about the future path

of interest rates and GDP growth rates

to be able to answer this question?

8.

• It depends. The government can

(cannot) maintain a permanent budget

deficit if the interest rate is lower

(higher) than the GDP growth rate.

107

Countercyclical fiscal policy

• Argues that increasing government

spending or reducing taxes during a

recession would mitigate the recession

–Suggested by Keynes in 1930s

(Keynesian policy)

• Rationale now for “fiscal stimulus”

package in Japan

• Discretionary versus automatic

108

Effect of the economy

on the budget deficit

• Budget deficit is cyclical

–Deficit rises in recessions

–Deficit falls during recoveries

and expansions

• To see the reason look at tax

revenues and expenditures

109

Government tax revenues depend

on the state of the economy

• when real GDP grows more rapidly,

proportional tax revenues rise

–more people working, higher

incomes

–people move into higher tax

brackets

110

Expenditures also depend on the economy

• When real GDP grows more rapidly, as in

a recovery, expenditures such as transfer

payments grow less rapidly

• When real GDP grows less rapidly or falls,

as in a recession, expenditures grow more

rapidly

– unemployment compensation rises

– welfare payments go up

– more people retire, increasing social

security payments

111

Net effect of real GDP on deficit

•

deficit = government spending

- tax revenue

•thus in a recession the

deficit will rise, and in a

recovery the deficit will fall

• Fill in P.17 table

112

The structural deficit

• The structural deficit is the deficit that

would exist if real GDP = potential GDP

• Also called full employment deficit

• Purpose is to take out (control for) the

effects of economic fluctuations in real

GDP on the deficit

• Changing structural deficit requires

– change in tax laws, size of government,...

113

4. The government budget deficit is

a) A stock variable.

b) A flow variable.

c) Neither a flow nor a stock variable.

d) Always increasing over time.

Answer: b

114

Countercyclical fiscal policy

• Argues that increasing government

spending or reducing taxes during a

recession would mitigate the recession

–Suggested by Keynes in 1930s

(Keynesian policy)

• Rationale now for “fiscal stimulus”

package in Japan

• Discretionary versus automatic

115

Fiscal Policy (P.16-7.2.6.)

• There was no such thing as fiscal policy until

John Maynard Keynes invented it in the

1930s

– He maintained that

• The only way out of the Depression was

to boost aggregate demand by

increasing government spending

• If we ran a big enough budget deficit, we

could jump-start the economy and, in

effect, spend our way out of the

depression

116

Copyright 2002 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

12-4

The Public Debt (P.18-7.2.6.3.3.)

• Differentiating between the Deficit and

the Debt

– The deficit occurs when government spending is

greater than tax revenue

– The debt is the cumulative total of all the budget

deficits less any surpluses

• Suppose that our deficit declined one year from $200

billion to $150 billion

• The national debt would still go up by $150 billion

• So every year that we have a deficit – even a declining

one – the national debt will go up

117

Copyright 2002 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

12-48

The Public Debt

• Is the national debt a burden that will have

to be borne by future generations?

– As long as we owe it to ourselves, the answer is

no

– If we did owe it mainly to foreigners (in 4-sector

model), and if they wanted it paid off, it could be

a great burden

– In the future, even if we never pay back one

penny of the debt, our children and our

grandchildren will have to pay hundreds of

billions of dollars in interest. At least to that

degree, the public debt will be a burden to

future generations

118

Copyright 2002 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

12-50

The Public Debt

National Debt, 1975-2000

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

1976

1978

1980

1982

1984

1986

1988

1990

1992

1994

1996

1998

2000

Economic Report of the President, 2000

119

Copyright 2002 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

12-49

The Automatic Stabilizers

• The automatic stabilizers protect us

from the extremes (peak & trough)

of the business cycle

– Personal Income and Payroll Taxes

• During recessions, tax receipts decline

• During inflations, tax receipts rise

– Personal Savings

• During recessions, saving declines

• During prosperity, saving rises

120

Copyright 2002 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

12-27

The Automatic Stabilizers

–Credit Availability

–Credit availability helps get us

through recessions

–Unemployment

Compensation

–During recessions more people

collect unemployment benefits

121

Copyright 2002 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

12-28

The Automatic Stabilizers

–The Corporate Profits Tax

• During recessions, corporations

pay much less corporate income

taxes

–Other Transfer Payments

• Welfare (or public assistance)

payments, Medical aid payments,

and food stamps rise during

recessions

122

Copyright 2002 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

12-29

•Consumption and Investment

Consumption and investment are two important

aggregates in macroeconomic models. An

autonomous change in one of them will cause the

level of national income to change, via the multiplier

effect. In this lesson, we take a closer look at

consumption and investment. Firstly, we consider

possible determinants of consumption demand

other than the one (i.e. income) in the simple

Keynesian model. Secondly, we examine two

hypotheses of consumption demand which are

used to explain the empirical data: the permanent

income hypothesis and the life-cycle hypothesis.

Lastly, we turn our attention to determinants of

123

investment.

Consumption

7.3.1.3.

C

Slope = MPC = APC

0

Income (years)

Figure 3 Permanent-income hypothesis

124

$

7.3.1.2.

Income stream

C

0

Age

Figure 4 Life-cycle income, consumption

and saving

125

Consumption

7.3.1.2.

C

Slope = MPC = APC =1

0

Permanent income

Figure 5 Life-cycle hypothesis

126

7.3.1.1.11.

C

Slope = MPC

rC

C

rYd

rC

rYd

0

Yd

Figure 6 Change in income distribution

127

E

0

E

Ye’

(a)

Ye

S’

S’

S

I

S

Yf Y

I

0

Ye’

Ye

Yf

(b)

Figure 9 The paradox of thrift

128

Y

Interest rate

E

S

S’

S

I’

S’

I

0

Ye

Yf

I

0

Loanable fund for

investment

(a)

(b)

Figure 10 The effect of increased saving

129

on investment

Y

Discretionary Policy and

Permanent Income

• Permanent income is income that

individuals expect to receive on

average over the long run

• To the extent that consumers base

spending decisions on their permanent

income, attempts to fine-tune the

economy through discretionary fiscal

policy will be less effective

130

Permanent Income Hypothesis

(Milton Friedman) 7.3.1.3.

• People gear their consumption to

their expected lifetime average

earnings more than to their current

income

– Apparently there are quite a few deviations

from the behavior predicted by the

permanent income hypothesis

131

Copyright Ó2002 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

5-49

7.3.1.2. Figure 8.6a Life-cycle

consumption, income, and saving

132

7.4 Investment (P. 23)

• “Investment” is the thing that really

makes our economy go and grow!

• Investment is any NEW

– Plant and equipment

• Investment is any NEW

– Additional inventory

• Investment is any NEW

– Residential housing

133

Copyright Ó2002 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

6-14

Investment in Plant and Equipment,

1960-2000 (in 1987 dollars)

1200

1100

1000

900

800

700

600

500

400

300

200

100

1960

1965

1970

1975

1980

1985

1990

1995

2000

There has been a strong upward trend in this investment sector over the last four

decades. Note the periodic downturns, especially during recession years 134

Copyright Ó2002 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

6-20

Inventory Investment, 1960-2000 (in

billions of 1987 dollars)

75

50

25

0

Ð25

1960

1965

1970

1975

1980

1985

1990

1995

2000

This is the most volatile sector of investment. Note that investment

was actually negative during three recessions

135

6-18

Copyright Ó2002 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

Residential Construction

• Involves replacing old housing as

well as adding to it

• Fluctuates considerably from

year to year

• Has mortgage interest rates play

a dominant role

136

Copyright Ó2002 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

6-21

Investment

• Investment is the most volatile sector in

our economy

– GDP = C + I + G + Xn

• Fluctuations in GDP are largely

fluctuations in investment

• Recessions are touched off by declines in

investment

• Recoveries are brought about by rising

investment

137

Copyright Ó2002 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

6-22

Determinants of the Level of

Investment

• Interest rate

• Sales outlook

• Expected rate of profit

• Technological change

• Business taxes

• Autonomous reasons

138

Copyright Ó2002 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

6-31

7.4.2. The Interest Rate

• You won’t invest if interest rates (cost)

are higher than MEC (benefit)

Interest rate = The interest paid / The amount borrowed

Assume you borrow $1000 for one year @ 12 %, how

much interest do you pay?

.12 =

X

$1000

X = $120

139

Copyright Ó2002 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

6-35

You Won’t Invest

If Interest Rates Are Too High

• In general, the lower the interest rate, the

more business firms will borrow

• To know how much they will borrow and

whether they will borrow, you need to

compare the interest rate with the

expected rate of profit

• Even if they are investing their own

money they need to make this

comparison

140

Copyright Ó2002 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

6-39

7.4.3. The Sales Outlook

• You won’t invest if the sales outlook

is bad

• If sales are expected to be strong the

next few months the business is

probably willing to add inventory

• If sales outlook is good for the next

few years, firms will probably

purchase new plant and equipment

141

Copyright Ó2002 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

6-32

Expected Rate of Profit

(ERP)

Expected Profits

ERP = ------------------------------------------Money Invested

How much is the ERP on a

$10,000 investment if you

expect to make a profit of

$1,650?

Copyright Ó2002 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

142

6-37

How much is the ERP on a

$10,000 investment if you expect

to make a profit of $1,650?

Expected Profits

ERP = ------------------------------------------Money Invested

$1,650

ERP = ------------------------------------------$10,000

ERP = .165 = 16.5 %

143

Copyright Ó2002 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

6-38

Why Do Firms Invest?

• Firm’s will only invest if the

expected profit rate is “high enough”

• Firms invest when

– Their sales outlook is good

– Their expected profit rate is high

• Even if firm’s invest their own

money, the interest rate is still a

consideration

144

Copyright Ó2002 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

6-40

C + I + G + Xn

10,000

10,000

C+I+G

8,000

C+I+G

8,000

C + I + G + Xn

6,000

6,000

4,000

4,000

2,000

2,000

45û

45û

2,000

4,000

6,000

8,000

Disposable income ($)

10,000

2,000

8,000

6,000

4,000

Disposable income ($)

10,000

Why is the C + I + G + Xn line lower than the C + I + G line?

Answer: It is lower because net exports (Xn) are negative

8-8

Copyright Ó2002 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

145