Handbook - University of Nottingham

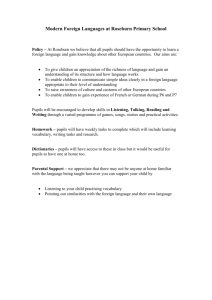

advertisement