Area4b-PowerPoint - Muskie School of Public Service

advertisement

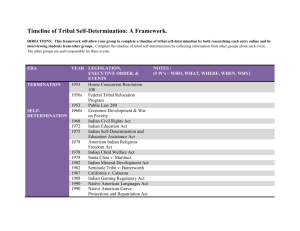

Engaging Community Stakeholders and Building Community Partnerships: State-Tribal Partnerships 1 Introduction Understanding the principles of Tribal Sovereignty, historical factors, and the Indian Child Welfare Act are key elements to developing positive state-tribal partnerships. This presentation will describe cultural distinctions that are the underpinnings of the statutes and protocols that guide the need for tribal engagement in child welfare. 2 The Context of the Relationship Between the Federal Government and Indian Tribes 3 4 Key Acronyms in “Indian Country” Native American Statistics - USA e Basic Numbers 4.1 million people reported as American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) 2000 US. Census 1.4 million children under the age of 18 562 Federally Recognized Tribes Native American children are placed in out-of-home care at a rate that is 3.6 times higher than the general population 5 Native American Statistics – (State) Federally recognized tribes = Total AI/AN population = Total AI/AN population <19 = 6 History’s Impact on Child Welfare in American Indian Communities 7 Key Laws Affecting Indian Tribes y Laws related to Indian Tribes 1819 Civilization Fund Act 1830 Removal Act 1887 Dawes Allotment Act 1924 Indian Citizenship Act 1934 Indian Reorganization Act 1953 Public Law 280 (limits of state jurisdiction) 1975 Indian Self-Determination Act 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act Court Rulings 8 Federal Policies of the 1800s American history and federal policy have impacted Indian tribes since first contact. 9 Civilization Fund Act-1819 The act intended to “civilize” and “Christianize” Indians through federal and private means. 10 Removal Act, 1830 Enacted to move Indians away from traditional homelands to “Indian Territory” west of the Mississippi 11 Indian Boarding Schools 1860s – Present Native children were removed from home and sent to military style boarding schools 12 Dawes Allotment Act, 1887 Indian land divided up in effort to turn Indians into nuclear families and farmers Introduction of “blood quantum” concept of tribal enrollment 13 Indian Citizenship Act, 1924 American Indians granted United States Citizenship. And while all Native Americans were now citizens, not all states were prepared to allow them to vote. Western states, in particular, engaged in all sorts of legal ruses to deny Indians the ballot. It was not until almost the middle of the 20th century that the last three states, Maine, Arizona and New Mexico, finally granted the right to vote to Indians in their states. 14 In 1953, Congress perceived inadequate law enforcement in Indian country and enacted Public Law 83-280 ("P.L. 280") to address the problem. 15 Public Law 83-280, 1953 Public Law 280 is a federal statute enacted by Congress in 1953. It enabled states to assume criminal, as well as civil, jurisdiction in matters involving Indians as litigants on reservation land. Previous to the enactment of Public Law 280, these matters were dealt with in either tribal and/or federal court. Essentially, Public Law 280 was an attempt by the federal government to reduce its role in Indian affairs. 16 Public Law 280, cont. Without tribal agreement, six states which were obligated to assume jurisdiction from the outset of the law: Alaska, California, Minnesota, Nebraska, Oregon, and Wisconsin. States that have assumed at least some jurisdiction since the enactment of Public Law 280 include: Nevada, South Dakota, Washington, Florida, Idaho, Montana, North Dakota, Arizona, Iowa, and Utah. After 1968, tribal agreement was required before state assumption of jurisdiction. 17 Federal Policies, 1950-60s Federal and private agency policies and practices impact Native American children and families- Indian Adoption Project (Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Child Welfare League of America)-1958 “Relocation Program” - 1950s 1960s: tribes began questioning placement rate of their children into non-Indian homes 18 Empowerment in the 1970s 1970s: Association on American Indian Affairs, New York, conducted surveys to find out extent of Indian child welfare issues. Studies found 25-35% of all Indian children had been removed from families and placed in non-Indian care Findings created and expressed national tribal concern, then action and advocacy In 1978 Congress passed Indian Child Welfare Act 19 Public Law 93-638 Indian Self-Determination Act, 1975 The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (PL93-638) gave official US sanction to promote Indian self-governance by the tribes. It did so by allowing the tribes to contract with federal agencies such as the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and Indian Health Services (IHS) to operate these formerly federally operated delivery systems through “638” contracts. 20 In April 1994, President Bill Clinton reinforced the longstanding federal policy supporting self-determination for Indian Nations and directed federal agencies to deal with Indian Nations on a government-to-government basis when tribal governmental or treaty rights are at issue. Each President since Lyndon Johnson has formally recognized the sovereign status of Indian Nations. 21 The five main principles of President Clinton’s policy required agencies to: (a) Operate within a government-to-government relationship with tribes (b) Consult, to the greatest extent practicable, with tribes prior to taking actions that affect tribes (c) Assess the impact of all federal plans, projects, programs, and activities on tribal trust resources, and assure those tribes’ rights and concerns are considered during the development of plans, projects, programs and activities (d) Take appropriate steps to remove procedural impediments to working directly and effectively with tribes on activities affecting the property or rights of tribes (e) Work cooperatively with other agencies to accomplish the goals of this memorandum 22 Tribal Sovereignty Sovereig nty ICW A Tribal Sovereignty Indian Self Determina tion Act Indian Reorganiza tion Treaties World View Reserva tions 23 Tribal governments are acknowledged in the U.S. Constitution and hundreds of treaties, federal laws, and court cases as distinct political entities with the inherent power to govern themselves. 24 The essence of tribal sovereignty is tribes’ ability to make and enforce their own laws and programs to promote the heath, safety, and welfare of tribal citizens within tribal territory. 25 Jurisdictional Issues Indian tribes, as sovereigns that pre-exist the federal Union, retain inherent sovereign powers over their members and territory, including the power to exercise criminal jurisdiction over Indians. 26 Tribes also have exclusive jurisdiction over such proceedings when they involve an Indian child who is a ward of the tribal court, regardless of where the child resides. Custody proceedings covered by the act include foster care placement, the termination of parental rights, and preadoptive and adoptive placement. 27 The federal government also has key responsibilities to tribes. The federal trust responsibility, one of the most important doctrines in federal Indian law, is the federal government’s obligation to protect tribal self-governance, lands, assets, resources, and treaty rights and to carry out the directions of federal statutes and court cases. The federal relationship with tribal governments also limits the role of state governments on tribal lands. 28 Common Components in Tribal Governments (note there are over 560 federally recognized distinct tribes) Tribal Members Tribal Constitution Tribal Council Rotating Positions elected every 2-3 years Tribal Law Enforcement Tribal Resolutions (Tribal Law) Tribal Codes Tribal Adminstrative Policy Human Services Economic Development Tribal Administration Tribal Court Social Services Natural Resource Development (Timber, Fish, water, mining) Tribal Enrollment Tribal Police Child Welfare Tribal Businesses Cultural Department Tribal Jail Mental Health Tribal Gaming Education Alcohol and Drugs Housing Community Health 29 The historic oppression of Native Peoples has resulted in an historic mistrust of state and federal governmental agencies. 30 Context for Tribal Engagement in Child Welfare American Indian cultural values are distinct from those that frame mainstream child welfare systems Mainstream child welfare systems have not always acknowledged these differences. Historical events have had a profound effect on tribal-state relationships 31 Federal child welfare legislation is not always viewed in a positive way by Native Americans. It was feared that laws, such as the Multi-ethnic Placement Act and Adoption and Safe Families Act could cause confusion with ICWA compliance The Adoption and Safe Families Act was initially viewed as just another method to find permanency for Native American children in adoption placements -- such as the 1950s Indian Adoption Project. 32 Indian Child Welfare Act -1978 The stated purpose of ICWA is “to protect the best interests of Indian children and to promote the stability and security of Indian tribes and families.” The act seeks to protect Indian children, tribes and culture by limiting state’s powers and by encouraging respect for tribal authority regarding the placement of Indian youth. The Indian Child Welfare Act played an important role in tribal empowerment in child welfare 33 The Indian Child Welfare Act has provided the impetus to improve tribal-state relationships and develop better understandings of cultural differences. 34 Cultural Competence Cultural competence is basic to eliminating disproportionate outcomes in child welfare. Definition of Organizational Cultural Competence: A set of congruent practice skills, attitudes, policies, and structures, which come together in a system, agency or among professionals and enable that system, agency or those professionals to work effectively in the context of cultural differences. (Cross 2004) States and Tribes working together can achieve cultural competence goals on behalf of the children. 35 Within most Native cultures, children are at the center of the community. They are encircled by extended family. Each member of their family has a traditionally prescribed responsibility to the children, both male and female. Grandparents Mother Father Uncles Aunts Older Sisters, Cousins Younger Sisters, Cousins Children Older Brothers, Cousins Younger Brothers, Cousins Friends/peers who Walk the same path of learning 36 World View The circle represents all relationships in the spirit world and on the earth. All beings encircle and protect the young. Good health is represented by a balance of spiritual, mental, emotional and physical well-being. When one element is unwell, every element is affected. The balance is necessary for individual, family and community health and wellness. 37 Current Tribal Child Welfare Issues Indian Child Welfare Act Compliance Recruitment and Retention of Native American Foster Families Adoption and Customary Adoption 38 Disproportionality in Child Welfare 35% of all American Indian children live in poverty; 10% of white children live in poverty. Indian children are victims of maltreatment at the same rate as other children, but maltreatment is substantiated twice as often as white children. Indian children experience placement three (3) times as often as white children. (CWLA 2003) In some states, Indian children represent 3560% of the children in out-of-home placements. 39 Building State – Tribal Partnerships in the CFSR Process begins with acknowledging the history and finding common ground. 40 The Best Interests of Indian Children are Served by: Creating State/Tribal Partnerships: Government to government communication Ensuring a seat at the policy table Consulting tribes at all levels Developing culturally competent systems of care: Legislatively Organizationally Professionally Adhering to the Indian Child Welfare Act: In the courts Administratively In direct service practice 41 Benefits of Collaborating With Tribes Clarifies the roles and responsibilities for the provision of care to tribal children to better serve Native American children and families Provides opportunities to improve outcomes for Native American children served by the child welfare agency Enhances mutual understanding of the role of governmental agencies in formulating or implementing policies that have tribal implications Statewide Assessment 42 States can engage tribal representatives in the Statewide Assessment process through the following activities: Providing formal notification of the CFSR to the tribal chairpersons/executive directors and social services directors; Request that they designate appropriate persons to be involved throughout this collaborative process; Using the CFSR process to formalize and enhance consultation and collaboration with tribes; and Consultation early in the process and engaging tribal representatives in meaningful roles, discussions of key issues, and decision-making. 43 • • • • • Developing materials about the CFSRs to share with tribal representatives; the documents should help them understand the benefits of the CFSR to their efforts to support children and families Including tribal representatives on the Statewide Assessment Team and associated work groups Inviting tribal representatives to participate in surveys and focus groups Holding key Statewide Assessment meetings or focus groups on tribal lands, in Indian Country, and/or on reservations, and at times convenient for tribal members Asking tribal representatives to identify any tribal data that they would like to share related to children served by the State child welfare agency and to help analyze State agency data 44 • • • • • Identifying child welfare issues related to Native American children served by the State agency, and exploring strategies for resolving those with tribal representatives, Identifying areas in which States and tribes could work together better to improve their child welfare systems Initiating cross-training opportunities for State and tribal child welfare agency staff Involving tribal representatives in drafting sections of the Statewide Assessment Soliciting tribal representatives’ comments on Statewide Assessment drafts 45 States can engage tribal representatives in the onsite review through the following activities: • • • • Notifying key tribal representatives about the timeline for planning and conducting the onsite review Inviting tribal representatives to designate staff to participate as case record reviewers during the onsite review Conducting stakeholder interviews with tribal representatives (and providing to them in advance of the interview a copy of the questions that they will be asked) Inviting tribal representatives to attend exit meetings or debriefings 46 States can engage tribal representatives in the PIP process through the following activities: Providing a copy of the Final Report to tribal representatives. Including tribal representatives on the PIP Team and associated work groups. Establishing Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs) or Agreement (MOAs). 47 • • • • Asking for assistance in identifying areas needing improvement. Engaging tribal representatives in analyzing State and local data to identify tribal issues and concerns and promising practices. Ensuring that the State’s ongoing QA efforts address issues concerning Native American children and include tribal representatives in measuring program improvement activities. Inviting tribal representatives to review and comment on PIP drafts. 48 • • • Teaming tribal representatives with State child welfare agency staff to implement and monitor PIP activities. Including tribal representatives on PIP evaluation teams. Identifying TA needs for both tribes and State child welfare agencies. 49 • • • Initiating cross-training opportunities for State and tribal child welfare agency staff about practice issues related to agency/tribe jurisdiction over child welfare cases. Holding PIP meetings in tribal communities. Acknowledging both the uniqueness of tribal child welfare circumstances and perspectives and the shared goal of improving outcomes for children and families. 50 Action Planning Next Steps 51