FINANCIAL MARKETS AND INSTITIUTIONS: A Modern Perspective

advertisement

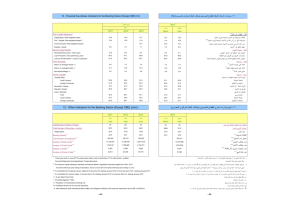

GESTIÓN BANCARIA Master en Banca y Finanzas Cuantitativas (QF), 2007 Santiago Carbó Valverde Universidad de Granada TEMA 1 LA INDUSTRIA DE SERVICIOS FINANCIEROS: LAS ENTIDADES DE DEPÓSITO TEMA 2 ¿POR QUÉ SON ESPECIALES LOS INTERMEDIARIOS BANCARIOS? TEMA 3 GOBIERNO Y ESTRUCTURA ORGANIZATIVA DE LA BANCA TEMA 4 LA INTERMEDIACIÓN FINANCIERA: LA ACTIVIDAD CREDITICIA TEMA 5 TÉCNICAS DE CONCESIÓN DE CRÉDITO: SCREENING, CREDIT SCORING Y MONITORING TEMA 6 EL RIESGO DE CRÉDITO: RIESGO EN LOS PRÉSTAMOS INDIVIDUALES Y EN CARTERA DE CRÉDITO TEMA 7 EL RIESGO DE TIPO DE INTERÉS: MODELOS DE MADURACIÓN, DE DURACIÓN Y DE “REPRICING” TEMA 8 EL RIESGO DE MERCADO TEMA 9 EL RIESGO DE LIQUIDEZ 2 Santiago Carbó Valverde Universidad de Granada scarbo@ugr.es Materiales docentes en: http://www.ugr.es/local/scarbo 3 Esquema de trabajo: Transparencias en inglés Presentaciones de papers en clase Examen final Referencia básica: SAUNDERS, A. Y M.M. CORNETT (2000): FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS MANAGEMENT: A MODERN PERSPECTIVE, 4ª EDICIÓN, MCGRAW HILL, NEW YORK, ESTADOS UNIDOS. 4 Tema 1 LA INDUSTRIA DE SERVICIOS FINANCIEROS: LAS ENTIDADES DE DEPÓSITO Why study Financial Markets and Institutions? They are the cornerstones of the overall financial system in which financial managers operate Individuals use both for investing Corporations and governments use both for financing 7 Overview of Financial Markets Primary Markets versus Secondary Markets Money Markets versus Capital Markets Foreign Exchange Markets 8 Primary Markets versus Secondary Markets Primary Markets markets in which users of funds (e.g. corporations, governments) raise funds by issuing financial instruments (e.g. stocks and bonds) Secondary Markets markets where financial instruments are traded among investors (e.g. Bolsa Madrid, NYSE, NASDAQ) 9 Money Markets versus Capital Markets Money Markets markets that trade debt securities with maturities of one year or less (e.g. Spanish Government bonds, U.S. Treasury bills) Capital Markets markets that trade debt (bonds) and equity (stock) instruments with maturities of more than one year 10 Money Market Instruments Outstanding, 1990-1999 ($Bn) 1400 1200 1000 800 600 400 200 0 1990 Commercial paper U.S. T-bills 1995 1999 Fed Funds and Repo Banker's accept. 11 Capital Market Instruments Outstanding, 1990-1999 ($Bn) 20000 15000 10000 5000 0 1990 Corp. stocks Comm/farm mort. Treas. Sec. U.S. gov owned agencies Bank and consumer loans 1995 1999 Res. Mortgages Corp. bonds St. & Loc. Gov. bonds U.S. gov sponsored agencies 12 Foreign Exchange Markets “FX” markets deal in trading one currency for another (e.g. dollar for yen) The “spot” FX transaction involves the immediate exchange of currencies at the current exchange rate The “forward” FX transaction involves the exchange of currencies at a specified date in the future and at a specified exchange rate 13 Overview of Financial Institutions (FIs) Institutions that perform the essential function of channeling funds from those with surplus funds to those with shortages of funds (e.g. banks, thrifts, insurance companies, securities firms and investment banks, finance companies, mutual funds, pension funds) 14 Flow of Funds in a World without FIs: Direct Transfer Financial Claims (Equity and debt instruments) Suppliers of Funds (Households) Users of Funds (Corporations) Cash Example: A firm sells shares directly to investors without going through a financial institution 15 Flow of Funds in a world with FIs: Indirect transfer FI (Brokers) Users of Funds Suppliers of Funds FI (Asset transformers) Financial Claims (Equity and debt securities) Financial Claims (Deposits and Insurance policies) 16 Types of FIs Commercial banks depository institutions whose major assets are loans and major liabilities are deposits Thrifts and savings banks depository institutions in the form of savings banks, savings and loans, credit unions, credit cooperatives Insurance companies financial institutions that protect individuals and corporations from adverse events (continued) 17 Securities firms and investment banks financial institutions that underwrite securities and engage in securities brokerage and trading Finance companies financial institutions that make loans to individuals and businesses Mutual Funds financial institutions that pool financial resources and invest in diversified portfolios Pension Funds financial institutions that offer savings plans for retirement 18 Services Performed by Financial Intermediaries Monitoring Costs aggregation of funds provides greater incentive to collect a firm’s information and monitor actions Liquidity and Price Risk provide financial claims to savers with superior liquidity and lower price risk 19 (continued) Transaction Cost Services transaction costs are reduced through economies of scale Maturity Intermediation greater ability to bear risk of mismatching maturities of assets and liabilities Denomination Intermediation allow small investors to overcome constraints imposed to buying assets imposed by large minimum denomination size 20 Services Provided by FIs Benefiting the Overall Economy Money Supply Transmission Depository institutions are the conduit through which monetary policy actions impact the economy in general Credit Allocation often viewed as the major source of financing for a particular sector of the economy (e.g. farming and real estate) (continued) 21 Services Provided by FIs Benefiting the Overall Economy Intergenerational Wealth Transfers life insurance companies and pension funds provide savers with the ability to transfer wealth from one generation to the next Payment Services efficiency with which depository institutions provide payment services directly benefits the economy 22 Risks Faced by Financial Institutions Interest Rate Risk Foreign Exchange Risk Market Risk Credit Risk Liquidity Risk Off-Balance-Sheet Risk Technology Risk Operation Risk Country or Sovereign Risk Insolvency Risk 23 Regulation of Financial Institutions FIs provide vital financial services to all sectors of the economy; therefore, their regulation is in the public interest In an attempt to prevent their failure and the failure of financial markets overall 24 Globalization of Financial Markets and Institutions Financial Markets became more global as the value of stocks traded in foreign markets soared Foreign bond markets have served as a major source of international capital Globalization also evident in the derivative securities market 25 Factors Leading to Significant Growth in Foreign Markets The pool of savings from foreign investors has increased International investors have turned to U.S. and other markets to expand their investment opportunities Information on foreign investments and markets is now more accessible (e.g. internet) Some mutual funds allow ability to invest in foreign securities with low transaction costs Deregulation has enhanced globalization of capital flows 26 Tema 2 ¿POR QUÉ SON ESPECIALES LOS INTERMEDIARIOS BANCARIOS? Why Are Financial Intermediaries Special? Objectives: Develop the tools needed to measure and manage the risks of FIs. Explain the special role of FIs in the financial system and the functions they provide. Explain why the various FIs receive special regulatory attention. Discuss what makes some FIs more special than others. 28 Without FIs Equity & Debt Households Corporations (net savers) (net borrowers) Cash 29 FIs’ Specialness Without FIs: Low level of fund flows. Information costs: Economies of scale reduce costs for FIs to screen and monitor borrowers Less liquidity Substantial price risk 30 With FIs FI Households Cash (Brokers) FI Corporations Equity & Debt (Asset Transformers) Deposits/Insurance Policies Cash 31 Financial Structure Puzzles: a way to explain the role of FIs stocks are not the most important source of external financing for businesses issuing debt and equity is not the main way that businesses finance operations indirect financing is more important than direct financing banks are the most important source of external funds for businesses financial industry is one of the most heavily regulated industries only large, well-known firms have access to the securities markets collateral is an important part of debt contracts for businesses and households debt contracts are complex and often contain many restrictions for the borrower 32 Transaction Costs information and other transaction costs in financial system can be substantial How do transaction costs affect investing? How can financial intermediaries reduce transaction costs? 33 Asymmetric Information one party to a transaction has better information to make decisions than the other party asymmetric information in financial market causes two main problems adverse selection moral hazard 34 Adverse Selection asymmetric information problem that occurs prior to a transaction examples of adverse selection result of adverse selection is that lenders may decide not to make loans if they can not distinguish between “good” and “bad” credit risks 35 Moral Hazard asymmetric information problem that occurs after a transaction risk that borrower will undertake risky activities that will increase the probability of default result of moral hazard is that lenders may decide not to make a loan 36 Lemons Problem idea presented in article by George Akerlof in terms of lemons in used car market used car buyers are unable to determine quality of car - good car or lemon? What amount is buyer willing to pay for this used car of unknown quality? How can buyer improve information on quality? 37 Lemons Problem in Stock and Bond Market asymmetric information prevents investors from identifying good and bad firms What price will these investors pay for stock? Who has better information about the firm? Which firms will “come to the market” for financing under these conditions? 38 Principal-Agent Problem define the principal-agent problem Who is the principal and who is the agent? What problem does a separation of ownership and control cause? How could we prevent principal-agent problem? 39 Solutions to Financing Puzzles lemons or adverse selection problem tells why marketable securities are not the primary source of financing situation is similar in corporate bond market tells why stocks are not the most important source of external financing 40 More Solutions to Financial Structure Puzzles importance of financial intermediaries explains importance of indirect financing explains why banks are most important source of external financing explains why markets are only available to large, well-known firms 41 Functions of FIs Brokerage function Acting as an agent for investors: e.g. Merrill Lynch, Charles Schwab Reduce costs through economies of scale Encourages higher rate of savings Asset transformer: Purchase primary securities by selling financial claims to households These secondary securities often more marketable 42 Role of FIs in Cost Reduction Information costs: Investors exposed to Agency Costs Role of FI as Delegated Monitor (Diamond, 1984) Shorter term debt contracts easier to monitor than bonds FI likely to have informational advantage 43 Services Performed by FIs Monitoring Costs Liquidity and Price Risk Transaction Cost Services Maturity Intermediation Denomination Intermediation 44 Services Provided by FIs Money Supply Transmission Credit Allocation Intergenerational Wealth Transfers Payment Services (continued) 45 Regulation of FIs Regulation is not costless Net regulatory burden. Safety and soundness regulation Monetary policy regulation Credit allocation regulation Consumer protection regulation Investor protection regulation Entry regulation 46 Changing Dynamics of Specialness Trends in the United States Decline in share of depository institutions. Increases in pension funds and investment companies. May be attributable to net regulatory burden imposed on depository FIs. Technological changes affect delivery of financial services and regulatory issues Potential for regulations to be extended to hedge funds Result of Long Term Capital Management disaster 47 Future Trends Weakening of public trust and confidence in FIs may encourage disintermediation Increased merger activity within and across sectors Citicorp and Travelers, UBS and Paine Webber More large scale mergers such as J.P. Morgan and Chase, and Bank One and First Chicago Growth in Online Trading Increased competition from foreign FIs at home and abroad Mergers involving world’s largest banks Mergers blending together previously separate financial services sectors 48 Tema 3 GOBIERNO Y ESTRUCTURA ORGANIZATIVA DE LA BANCA “It is the ability to foretell what is going to happen tomorrow, next week, next month, and next year. And to have the ability afterwards to explain why it didn’t happen.” Sir Winston Churchill What are Financial Intermediaries (FIs)? Financial Securities: contingent claims on future cash flows – debt, equity, derivatives, hybrids. All firms’ liabilities & net worth are predominately comprised of financial securities. But most firms hold real assets such as inventory, plant & equipment, buildings. FIs’ assets are predominately comprised of financial securities. 51 Transparent, Transluscent and Opaque FIs Financial Intermediation: The Flow of Funds and Primary Securities Funds Surplus Units Brokers Funds Deficit Units Funds Surplus Units Dealers Funds Deficit Units Funds Surplus Units Underwriters Investment Banks Funds Deficit Units Funds Surplus Units Mutual Funds Funds Deficit Units Funds Surplus Units Banks Funds Deficit Units Funds Surplus Units Insurance Companies Funds Deficit Units 52 What Services Do FIs Provide? Information Liquidity Reduced Transaction Costs Transmission of Monetary Policy Credit Allocation Payment Services Intergenerational Wealth Transfer 53 FIs are the most regulated of all firms Safety and Soundness Regulation Deposit Insurance Monetary Policy Regulation Reserve Requirements Credit Allocation Regulation (eg., mortgages) Consumer Protection Regulation Community Reinvestment Act, Home Mortgage Disclosure Act, Truth in Lending Protection Investor Protection Regulation Entry Regulation 54 Types of FIs Depository Institutions Insurance Companies Securities Firms and Investment Banks Mutual Funds Finance Companies Distinctions blurred by the GrammLeach-Bliley Act of 1999 that created Financial Holding Companies (FHCs). 55 Features Common to Most FIs High Amount of Financial Leverage Low equity/assets ratios. Capital requirements. Off-balance sheet items Contingent claims that under certain circumstances may eventually become balance sheet items (ex. Derivatives, commitments) Revenue: Interest Income & Fees Costs: Interest Expenses and Personnel 56 Depository Institutions Commercial Banks: accept deposits and make loans to consumers and businesses. Money Center Banks: Citigroup, Bank of NY, BankOne, Bankers Trust (Deutschebank), JP Morgan Chase and HSBC Bank USA. Savings Associations (S&Ls) Qualified Thrift Lender (QTL) mortgages must exceed 65% of thrift’s assets. Savings Banks Use deposits to fund mortgages & other assets. Credit Unions and Credit cooperatives Nonprofit mutually owned institutions (owned by depositors). 57 Overview of Depository Institutions In this segment, we explore the depository FIs: Size, structure and composition Balance sheets and recent trends Regulation of depository institutions Depository institutions performance 58 Products of FIs Comparing the products of FIs in 1950, to products of FIs in 2003: Much greater distinction between types of FIs in terms of products in 1950 than in 2003 Blurring of product lines and services over time Wider array of services offered by all FI types 59 Specialness of Depository FIs Products on both sides of the balance sheet Loans Business and Commercial Deposits 60 Other outputs of depository FIs Other products and services 1950: Payment services, Savings products, Fiduciary services By 2003, products and services further expanded to include: Underwriting of debt and equity, Insurance and risk management products 61 Size of Depository FIs Consolidation has created some very large FIs Combined effects of disintermediation, global competition, regulatory changes, technological developments, competition across different types of FIs 62 Largest Depository Institutions in the US Total Assets ($Billions) Citigroup J.P. Morgan Chase* Bank of America** Wells Fargo Wachovia Bank One* Washington Mutual Fleet Boston** U.S. Bancorp SunTrust Banks $1,208.9 770.9 736.4 393.9 388.0 326.6 275.2 200.2 188.8 181.0 63 Organization of Depository Institutions Commercial Banks Largest depository institutions are commercial banks. Differences in operating characteristics and profitability across size classes. Notable differences in ROE and ROA as well as the spread Thrifts S&Ls Savings Banks Credit Unions Mix of very large banks with very small banks 64 Functions & Structural Differences Functions of depository institutions Regulatory sources of differences across types of depository institutions. Structural changes generally resulted from changes in regulatory policy. Example: changes permitting interstate branching Reigle-Neal Act (1994) in the US In Spain, deregulation in 1989 concerning savings banks operations 65 Commercial Banks Primary assets: Real Estate Loans: $2,272.3 billion C&I loans: $870.6 billion Loans to individuals: $770.5 billion Investment security portfolio: $1,789.3 billion Of which, Treasury bonds: $1,005.8 billion Inference: Importance of Credit Risk 66 Commercial Banks Primary liabilities: Deposits: $5,028.9 billion Borrowings: $1,643.3 billion Other liabilities: $238.2 billion Inference: Highly leveraged 67 Small Banks, US C&I 14% Credit Card 1% Consumer 8% Real Estate 63% Other 14% 68 Large Banks, US C&I 18% Credit Card 7% Real Estate 44% Consumer 10% Other 21% 69 Structure and Composition Shrinking number of banks: 14,416 commercial banks in 1985 12,744 in 1989 7,769 in 2004 Mostly the result of Mergers and Acquisitions M&A prevented prior to 1980s, 1990s Consolidation has reduced asset share of small banks 70 Structure & Composition of Commercial Banks Financial Services Modernization Act 1999 Allowed full authority to enter investment banking (and insurance) Limited powers to underwrite corporate securities have existed only since 1987 71 Composition of Commercial Banking Sector Community banks Regional and Super-regional Access to federal funds market to finance their lending activities Money Center banks Bank of New York, Deutsche Bank (Bankers Trust), Citigroup, J.P. Morgan Chase, HSBC Bank USA declining in number 72 Balance Sheet and Trends Business loans have declined in importance Offsetting increase in securities and mortgages Increased importance of funding via commercial paper market Securitization of mortgage loans 73 Some Terminology Transaction accounts Negotiable Order of Withdrawal (NOW) accounts (“cuenta a la vista”) Money Market Mutual Fund Negotiable CDs (“certificados de depósito”): Fixed-maturity interest bearing deposits with face values over $100,000 that can be resold in the secondary market. 74 Off-balance Sheet Activities Heightened importance of off-balance sheet items Large increase in derivatives positions is a major issue Standby letters of credit Loan commitments When-issued securities Loans sold 75 Trading and Other Risks Allied Irish / Allfirst Bank $750 million loss (2001) National Australian Bank $450 million loss (2004) Failure of the U.K. investment bank Barings The Bankruptcy of Orange County in California. 76 Other Fee-generating Activities Trust services Correspondent banking Check clearing Foreign exchange trading Hedging Participation in large loan and security issuances Payment usually in terms of noninterest bearing deposits 77 Key Regulatory Agencies FDIC and the Office of the Comprotroller of the Currency in the US. European Central Bank National central banks National Governments Regional Governments 78 Web Resources For more detailed information on the regulators, visit: http://www.ecb.int http://www.bde.es http://www.fdic.gov http://www.occ.treas.gov http://federalreserve.gov 79 Banking and Ethics Some cases for the US: Bank of America and Fleet Boston Financial 2004 J.P. Morgan Chase and Citigroup 2003 role in Enron Riggs National Bank and money laundering concerns 2003 80 Savings Institutions Comprised of: Savings and Loans Associations Savings Banks Effects of moral hazard and regulator forbearance. Quite a debate worldwhile. 81 Savings Institutions: Recent Trends Industry is smaller overall Intense competition from other FIs mortgages for example Concern for future viability in certain countries. 82 Credit Unions Nonprofit depository institutions owned by member-depositors with a common bond. Exempt from taxes and Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) in the US. Expansion of services offered in order to compete with other FIs. Very important in certain European countries (Germany, Spain). 83 Global Issues Near crisis in Japanese Banking Eight biggest banks reported positive sixmonth profits China Deterioration, NPLs (nonperforming loans) at 50% levels Opening to foreign banks (WTO entry) German bank problems in early 2000s Implications for future competitiveness 84 Largest Banks in the World Bank Assets ($Millions) Citigroup (USA) 1,097,000 Mizuho Financial Group (Japan) 945,688 UBS (Switzerland) 825,000 Sumitomo Mitsui Fin. (Japan) 802,674 Deutsche Bank (Germany) 794,984 Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi (Japan) 789,495 85 Tema 4 LA INTERMEDIACIÓN FINANCIERA: LA ACTIVIDAD CREDITICIA. Análisis por tipos de instituciones Commercial Banks Represent the largest group of depository institutions measured by asset size. Perform functions similar to those of savings institutions and credit unions - they accept deposits (liabilities) and make loans (assets) Liabilities include nondeposit sources of funds such as subordinated notes and debentures Loans are broader in range, including consumer, commercial, international, and real estate 87 Differences in Balance Sheets Depository Institutions Assets Loans Liabilities Deposits Other financial assets Other nonfinancial assets Nonfinancial Firms Assets Deposits Liabilities Loans Other financial assets Other liabilities and equity Other nonfinancial assets Other liabilities and equity 88 Commercial Bank Balance Sheet Assets Total cash assets………………. $ 253.8 U.S. gov securities…………… $ 801.4 Other…………………………. 391.6 Investment securities………….. 1,193.0 Interbank loans………………. 223.0 Loans exc. Interbank………… 3,314.3 Comm. and Indust…………..$ 948.5 Real estate…………………… 1,343.0 Individual……………………. 496.4 All other……………………… 526.4 Less: Reserve for losses……… 58.7 Total loans……………………… $3,478.6 Other assets…………………….. 347.6 Total assets…………………….. $5,273.0 4.8% 22.6% 66.0% 6.6% 89 Commercial Bank Balance Statement (liabilities) Liabilities and Equity Transaction accounts…………… Nontransaction accounts………... Total deposits…………………… Borrowings……………………… Other liabilities………………….. Total liabilities………………….. Equity…………………………… $ 667.4 2,688.5 12.8% 54.4% $3,355.9 1,006.0 462.3 $4,824.2 448.8 21.3% 2.8% 8.7% *Aggregate balance sheet and percentage distributions for all U.S. commercial banks as of May 26, 1999 in billions of dollars 90 The importance of lending (I) The history of banking institutions is the history of lending itself. Banks solve asymmetric information problems through lending. The relevance of lending is not exclusive of commercial banks. It is even more important at other depository instituions (in relative terms). 91 The importance of lending (II) Lending and the resolution of asymmetric information problems are usually studied within an IO perspective. A large amount of contracts is needed to achieve efficiency and to solve asymmetric information problems: relevance of scale and scope economies and efficiency. 92 Economies of Scale and Scope Economies of scale - the degree to which a firm’s average unit costs of producing financial services fall as its output of services increase Economies of scope - the degree to which a firm can generate cost synergies by producing multiple financial service products Megamerger - the merger of banks with assets of $1 billion or more X efficiencies - cost savings due to the greater managerial efficiency of the acquiring firm 93 Measuring Economies of Scale ACi = TC i Si Where: ACi = Average costs of the ith bank TCi = Total costs of the ith bank Si = Size of the bank measured by assets, deposits or loans 94 Economies of Scale and the Effect of Technology Improvement Average Cost Old Technology AC1 New Technology AC2 Size 0 95 Economies of Scope By offering more services to a given customer; revenue can be enhanced costs can be reduced Cost economies of scope investments in one financial service (such as lending) may reduce costs to produce financial services in other areas (such as securities underwriting or brokerage) Revenue economies of scope 96 Bank Size and Activities Large banks have easier access to capital markets and can operate with lower amounts of equity capital Large banks tend to use more purchased funds (such as fed funds) and have fewer core deposits Large banks lend to larger corporations which means that their interest rate spread is narrower the difference between lending and deposit rates Large banks are more diversified and generate more noninterest income 97 Industry Performance Provision for loan losses - bank management’s recognition of expected bad loans for the period Net charge-offs - actual losses on loans and leases Net operating income - income before taxes and extraordinary items 98 Thrift Institutions and Savings & Cooperative Banks Savings Associations concentrated primarily on residential mortgages Savings Banks large concentration of residential mortgages commercial loans corporate bonds corporate stock Credit Unions consumer loans funded with member deposits 99 IN THE US: Regulator forbearance - a policy of the FSLIC not to close economically insolvent FIs, allowing them to continue in operation IN EUROPE: More variety and diversity. All sorts of savings banks and credit cooperative structures (private, public, semi-public). Mutual organization - an institution in which the liability holders are also the owners: THE CASE OF PROXIMITY BANKING: COMMUNITY BANKS IN THE US SAVINGS BANKS IN EUROPE 100 Financial Statements of Commercial Banks Report of condition - balance sheet of a commercial bank reporting information at a single point in time Report of income - income statement of a commercial bank reporting revenues, expenses, net profit or loss, and cash dividends over a period of time Retail bank - one that focuses its business activities on consumer banking relationships Wholesale bank - one that focuses its business activities on commercial banking relationships 101 Assets Four major subcategories cash and balances due from other depository institutions vault cash, deposits at the Federal Reserve, deposits at other FIs, and cash items in the process of collection investment securities interest-bearing deposits at other FIs, fed funds sold, RPs, U.S. Treasury and agency securities, securities issued by states and political subdivisions, mortgagebacked securities, and other debt and equity securities loans and leases other assets premises and fixed assets, real estate owned, investments in unconsolidated subsidiaries, intangible assets, other fees receivable 102 Liabilities NOW account - negotiable order of withdrawal account, similar to a demand deposit with minimum balance MMDAs - money market deposit accounts with retail savings accounts and limited checking account (IN THE US) Other savings deposits - other than MMDAs (IN EUROPE): basically customer (savings and term) deposits) 103 Liabilities Negotiable instrument - an instrument whose ownership can be transferred in the secondary market Purchased funds - rate-sensitive funding sources of the bank (ej. “cesiones temporales de activos”). 104 Equity Capital Preferred and common stock (listed at par value) Surplus or additional paid-in capital Retained earnings Regulations require banks to hold a minimum level of equity capital to act as a buffer against losses from their on- and off-balance sheet assets 105 Off-Balance-Sheet Assets and Liabilities Contingent assets and liabilities that may affect the future status of the FIs balance sheet OBS activities grouped into 5 major categories Loan commitments - contractual commitment to loan to a firm a certain maximum amount at given interest rate terms up-front fee - fee charged for making funds available through a loan commitment back-end fee - fee charged on the unused component of a loan commitment (continued) 106 Loans Sold (securitization) loans that a bank originated and then sold to other investors that may be returned (with recourse) to the originating institution in the future recourse - the ability to put an asset or loan back to the seller should the credit quality of that asset deteriorate Derivative Contracts futures, forward, swap, and option positions taken by the FI for hedging or other purposes 107 Income Statement Interest Income Interest Expenses Net Interest Income Provision for Loan Losses Noninterest Income Noninterest Expense Income before Taxes and Extraordinary Items Income Taxes Extraordinary Items Net Income 108 The Direct Relationship between the Income Statement and the Balance Sheet N NI = M rnAn - rmLm n=1 P + NII - NIE - T m=1 where NI = Bank’s net income An = Dollar value of the bank’s nth asset Lm = Dollar value of the bank’s nth liability rn = Rate earned on the bank’s nth asset rm = Rate paid on the bank’s nth liability P = Provision for loan losses NII = noninterest income earned, including OBS NIE = noninterest expenses incurred T = Bank’s taxes N = number of assets the bank holds M = number of liabilities the bank holds 109 Financial Statement Analysis Using a Return on Equity Framework Time series analysis - analysis of financial statements over a period of time Cross-sectional analysis - analysis of financial statements comparing one firm with others Return on equity (ROE) - measures overall profitability of the FI per dollar of equity ROE = Net income Total Assets Total Assets Total equity capital = ROA EM 110 Return on Assets and Its Components Return on Assets (ROA) - measures profit generated relative to the FI’s assets ROA = Net Income Total operating income Total operating income Total assets = PM (profit margin) AU (assets utilization) 111 Profit Margin Profit Margin (PM) - measures the ability to pay expenses and generate income from interest and noninterest income Interest expense ratio = Interest expense Total operating income Provision for loan loss ration = Provision for loan losses Total operating income Noninterest expense ratio = Noninterest expense Total operating income Tax Ratio = Income taxes Total operating income 112 Asset Utilization Asset utilization (AU) - measures the amount of interest/ noninterest income generated per dollar of total assets AU = Total operating income = Interest + Noninterest Total assets income income ratio ratio 113 Net Interest Margin Net interest margin - interest income minus interest expense divided by earning assets Net interest = margin = Net interest income Earning assets Interest income - Interest expense Investment securities + Net loans and leases 114 Spread Spread - the difference between lending and deposit rates spread = Interest income Interest expense Earning assets Interest-bearing liabilities 115 Overhead Efficiency Overhead efficiency - a bank’s ability to generate noninterest income to cover noninterest expenses Overhead efficiency = Noninterest income Noninterest expense 116 Tema 5 Técnicas de concesión de crédito: screening, credit scoring y monitoring Risks Faced by Financial Intermediaries Credit Risk Liquidity Risk Interest Rate Risk Market Risk Off-Balance-Sheet Risk Foreign Exchange Risk Country or Sovereign Risk Technology Risk Operational Risk Insolvency Risk 118 Market Risk Incurred in trading of assets and liabilities (and derivatives). Examples: Barings & decline in ruble. DJIA dropped 12.5 percent in two-week period July, 2002. Heavier focus on trading income over traditional activities increases market exposure. Trading activities introduce other perils as was discovered by Allied Irish Bank’s U.S. subsidiary, AllFirst Bank when a rogue trader successfully masked large trading losses and fraudulent activities involving foreign exchange positions 119 Market Risk Distinction between Investment Book and Trading Book of a commercial bank Heightened focus on Value at Risk (VAR) Heightened focus on short term risk measures such as Daily Earnings at Risk (DEAR) Role of securitization in changing liquidity of bank assets and liabilities 120 Credit Risk Risk that promised cash flows are not paid in full. Firm specific credit risk Systematic credit risk High rate of charge-offs of credit card debt in the 1980s, most of the 1990s and early 2000s Credit card loans (and unused balances) continue to grow 121 Implications of Growing Credit Risk Importance of credit screening Importance of monitoring credit extended Role for dynamic adjustment of credit risk premia Diversification of credit risk 122 Off-Balance-Sheet Risk Striking growth of off-balance-sheet activities Letters of credit Loan commitments Derivative positions Speculative activities using offbalance-sheet items create considerable risk 123 Technology and Operational Risk Risk that technology investment fails to produce anticipated cost savings. Risk that technology may break down. CitiBank’s ATM network, debit card system and on-line banking out for two days Wells Fargo Bank of New York: Computer system failed to recognize incoming payment messages sent via Fedwire although outgoing payments succeeded 124 Technology and Operational Risk Operational risk not exclusively technological Employee fraud and errors Losses magnified since they affect reputation and future potential Merrill Lynch $100 million penalty 125 Country or Sovereign Risk Result of exposure to foreign government which may impose restrictions on repayments to foreigners. Often lack usual recourse via court system. Examples: • Indonesia Argentina • Malaysia Russia • Thailand. South Korea 126 Country or Sovereign Risk In the event of restrictions, reschedulings, or outright prohibition of repayments, FIs’ remaining bargaining chip is future supply of loans Weak position if currency collapsing or government failing Role of IMF Extends aid to troubled banks Increased moral hazard problem if IMF bailout expected 127 Liquidity Risk Risk of being forced to borrow, or sell assets in a very short period of time. Low prices result. May generate runs. Runs may turn liquidity problem into solvency problem. Risk of systematic bank panics. Example: 1985, Ohio savings institutions insured by Ohio Deposit Guarantee Fund Interaction of credit risk and liability risk Role of FDIC (see Chapter 19) 128 Insolvency Risk Risk of insufficient capital to offset sudden decline in value of assets to liabilities. Continental Illinois National Bank and Trust Original cause may be excessive interest rate, market, credit, offbalance-sheet, technological, FX, sovereign, and liquidity risks. 129 Credit Risk Management An FI’s ability to evaluate information and control and monitor borrowers allows them to transform financial claims of household savers efficiently into claims issued to corporations, individuals, and governments An FI accepts credit risk in exchange for a fair return sufficient to cover the cost of funding (e.g., covering the cost of borrowing, or issuing deposits) 130 Credit Analysis Real Estate Lending residential mortgage loan applications are among the most standardized of all credit applications Two considerations the applicant’s ability and willingness to make timely interest and principal repayments the value of the borrower’s collateral GDS (gross debt service) ratio - gross debt service ratio calculated as total accommodation expenses (mortgage, lease, condominium, management fees, real estate taxes, etc.) divided by gross income TDS (total debt service) ratio - total debt ratio calculated as total accommodation expenses plus all other debt service payments divided by gross income 131 Credit Scoring Credit scoring system a mathematical model that uses observed loan applicant’s characteristics to calculate a score that represents the applicant’s probability of default Perfecting collateral ensuring that collateral used to secure a loan is free and clear to the lender should the borrower default Foreclosure taking possession of the mortgaged property to satisfy a defaulting borrower’s indebtedness Power of sale taking the proceedings of the forced sale of property to satisfy the indebtedness 132 Credit Scoring Consumer (individual) and Small-business lending techniques for scoring consumer loans very similar to mortgage loan credit analysis but more emphasis placed on personal characteristics such as annual gross income and the TDS score small-business loans more complicated and has required FIs to build more sophisticated scoring models combining computer-based financial analysis of borrower financial statements with behavioral analysis of the owner 133 Ratio Analysis Historical audited financial statements and projections of future needs Calculation of financial ratios in financial statement analysis Relative ratios offer information about how a business is changing over time Particularly informative when they differ either from an industry average or from the applicant’s own past history 134 Calculating Ratios Liquidity Ratios Current Ratio = Current assets Current liabilities Quick ratio = Cash + Cash equivalents + Receivables Current liabilities (continued) 135 Asset Management Ratios Number of days sales = Accounts receivable x 365 in receivables Credit sales Number of days = Inventory x 365 in inventory Cost of goods sold Sales to working = Sales capital Working capital Sales to fixed = Sales assets Fixed assets Sales to total assets = Sales Total assets (continued) 136 Debt and Solvency ratios Debt-asset ratio = Short-term liabilities + Long-term liabilities Total assets Fixed-charge = Earnings available to meet fixed charges coverage ratio Fixed charges Cash-flow-to-debt = EBIT + Depreciation ratio Debt where EBIT represents earnings before interest and taxes (continued) 137 Profitability Ratios Gross margin = Gross profit Sales Income to Sales = EBIT Sales Operating profit margin = Operating profit Sales Return on assets = EAT Average total assets Return on equity = EAT Total equity Dividend payout = Dividends EAT where EAT represents earnings after taxes, or net income 138 Common Size Analysis and After the Loan Analyst can divide all income statement amounts by total sales revenue and all balance sheet amounts by total assets Year to year growth rates give useful ratios for identifying trends Loan covenants reduce risk to lender Conditions precedent those conditions specified in the credit agreement or terms sheet for a credit that must be fulfilled before drawings are permitted 139 Large Commercial and Industrial Lending Very attractive to FIs because transactions are often large enough make them very profitable even though spreads and fees are small in percentage FIs act as broker, dealer, and adviser in credit management The standard methods of analysis used for midmarket corporates applied to large corporate clients but with additional complications Financial ratios such as the debt-equity ratio are usually key factors for corporate debt 140 Altman’s Z-Score Used for analyzing publicly traded manufacturing firms Z = 1.2X1 + 1.4X2 + 3.3X3 + 0.6X4 + 1.0X5 where Z = an overall measure of the borrower’s default risk X1 = Working capital/Total assets ratio X2 = Retained earnings/Total assets ratio X3 = Earnings before interest and taxes/Total assets ratio X4 = Market value of equity/Book value of long-term debt ratio X5 = Sales/Total assets ratio The higher the value of Z, the lower the default risk 141 The KMV Model Banks can use the theory of option pricing to assess the credit risk of a corporate borrower The probability of default is positively related to: the volatility of the firm’s stock the firm’s leverage A model developed by KMV corporation is being widely used by banks for this purpose 142 Calculating the Return on a Loan A number of factors impact the promised return that an FI achieves on any given dollar loan the interest rate on the loan any fees relating to the loan the credit risk premium on the loan the collateral backing the loan other nonprice terms (such as compensating balances and reserve requirements) 143 Return on Assets (ROA) 1 + k = 1 + f + (L + m) 1 - (b(1 - R)) where k = the contractually promised gross return on the loan f = direct fees, such as loan origination fee L = base lending rate m = risk premium b = compensating balances R = reserve requirement charge 144 Risk-Adjusted Return on Capital (RAROC) Rather than evaluating the actual or promised annual cash flow on a loan as a percentage of the amount lent (ROA), the lending officer balances the loan’s expected income against the loan’s expected risk RAROC = One-year income on a loan/Loan (asset risk or capital at risk 145 Tema 6 EL RIESGO DE CRÉDITO: RIESGO EN LOS PRÉSTAMOS INDIVIDUALES Y EN CARTERA DE CRÉDITO Overview The aim is to discuss the existence of different types of loans, and the analysis and measurement of credit risk on individual loans. This is important for purposes of: Pricing loans and bonds Setting limits on credit risk exposure 147 Credit Quality Problems Problems with junk bonds, residential and farm mortgage loans. More recently, credit card and auto loans. Crises in Asian countries such as Korea, Indonesia, Thailand, and Malaysia. Default of one major borrower can have significant impact on value and reputation of many FIs Emphasizes importance of managing credit risk 148 Credit Quality Problems Over the early to mid 1990s, improvements in NPLs (non-performing loans) for large banks and overall credit quality. Late 1990s concern over growth in low quality auto loans and credit cards, decline in quality of lending standards. Exposure to Enron. Late 1990s and early 2000s: telecom companies, tech companies, Argentina, Brazil, Russia, South Korea New types of credit risk related to loan guarantees and off-balance-sheet activities. Increased emphasis on credit risk evaluation. 149 Types of Loans: C&I (commercial and industrial) loans: secured and unsecured Syndication Spot loans, Loan commitments Decline in C&I loans originated by commercial banks and growth in commercial paper market. Downgrades of Ford, General Motors and Tyco RE (real state) loans: primarily mortgages Fixed-rate, variable rates Mortgages can be subject to default risk when loan-to-value declines. 150 *CreditMetrics (sistema patentado) “If next year is a bad year, how much will I lose on my loans and loan portfolio?” VAR = P × 1.65 × s Neither P, nor s observed. Calculated using: (i)Data on borrower’s credit rating; (ii) Rating transition matrix; (iii) Recovery rates on defaulted loans; (iv) Yield spreads. 151 * Credit Risk+ (sistema patentado) Developed by Credit Suisse Financial Products. Based on insurance literature: Losses reflect frequency of event and severity of loss. Loan default is random. Loan default probabilities are independent. Appropriate for large portfolios of small loans. Modeled by a Poisson distribution. 152 Credit risk measurement has evolved dramatically over the last 20 years. The five forces made credit risk measurement become more important than ever before: (i) A worldwide structural increase in the number of bankruptcies. (ii) A trend towards disintermediation by the highest quality and largest borrowers. 153 (iii) More competitive margins on loans. (iv) A declining value of real assets in many markets. (v) A dramatic growth of off-balance sheet instrument with inherent default risk exposure, including credit risk derivatives. 154 Responses of academics and practitioners: (i) Developing new and more sophisticated credit-scoring/early-warning systems (ii) Moved away from only analyzing the credit risk of individual loans and securities towards developing measures of credit concentration risk (iii) Developing new models to price credit risk (e.g. RAROC) (iv) Developing models to measure better the credit risk of off-balance sheet instruments 155 Measurement of the Credit risk of Offbalance Sheet Instruments The expansion in off-balance sheet instrument – such as swaps, options, forwards, futures, etc. Default risk of the instruments have been concerned. It has been reflected in the BIS risk-based capital ratio. The models like KMV, OPM can be applied to measure the probability of default on off-balance sheet instruments. 156 Measurement of the Credit risk of Offbalance Sheet Instruments (cont.) Differences between the default risk on loans and off-balance sheet instruments: (i) Even if the counter-party is in financial distress, it will only default on out-of-the-money contracts. (ii) For any given probability of default, the amount lost on default is usually less for off-balance sheet instruments than for loans. 157 Measures of credit concentration risk The measurement of credit concentration risk is also important Early approaches to concentration risk analysis were based either on: (i) Subjective analysis (ii) Limiting exposure in an area to a certain percent of capital (e.g. 10%) (iii)Migration analysis 158 Measures of credit concentration risk (cont.) Modern portfolio theory (MPT) - By taking advantage of its size, an FI can diversify considerable amounts of credit risk as long as the returns on different assets are imperfectly correlated increasingly being applied to loans and other fixed income instruments recently 159 Accounting based credit-scoring systems Four methodological approaches to developing multivariate creditscoring systems: (i) The linear probability model (ii) The logit model (iii)The probit model (iv)The discriminant analysis model 160 Other (newer) models of credit risk measurement Three criticisms of accounting based credit-scoring models 1. Accounting data fails to pick up fastmoving changes in borrower conditions 2. The world is inherently non-linear 3. They are only tenuously linked to an underlying theoretical model 161 Other (newer) models –KMV model (cont.) Step 2: calculate distance to default (D) D = (A-B)/ σA Step 3: calculate EDF Probability distribution of asset value (A) in one year value A Distance to default B EDF (A<B) 0 1 time 162 Other (newer) models- Term structure applications Jonkhart(1979), seek to impute implied probabilities of default(1-p) from term structure of yield spreads between default free and risky corporate securities. -the spreads between Treasury strips and zero-coupon corporate bond reflect perceived credit risk exposures Corporate bond yield T-bond 1 2 maturity 163 APPENDIX: Bank regulation and credit risk: an example from Basel II and savings banks Historically, regulation has limited who can: open or charter new banks and what products and services banks can offer. Imposing barriers to entry and restricting the types of activities banks can engage in clearly enhance safety and soundness, but also hinder competition. 164 It assumed that the markets for bank products, largely bank loans and deposits, could be protected and that other firms could not encroach upon these markets. Not surprisingly, investment banks, hybrid financial companies, insurance firms, and others found ways to provide the same products as banks across different geographic markets. 165 However, there is another type of regulation that has concentrated most of the attention in the last three decades, the bank capital regulation. Changes in reserve requirements …directly affect the amount of legal required reserves and thus change the amount of money a bank can lend out. The main recent example is BASEL II. 166 Basel 2 is a ‘step change’ in the regulation of capital adequacy. It will alter the industry ‘frame of reference’ for banks in many ways: Regulators are clearly recognizing market realities and seeking a much closer congruence between regulatory and economic capital. The new proposals are more complex and sophisticated than earlier schemes. They will also have to evolve as market conditions, technology and financial management techniques develop. 167 The calibration exercises that have resulted from the various Quantitative Impact Studies (QIS) are targeted (initially at least) to deliver broadly the same amount of capital as the current Accord. However, the mix of capital charges will change significantly with the wider range of risk weights and greater risk sensitivity of Basel 2. Basel 2 will clearly be much more risksensitive in assigning capital charges. Mortgage lending and lending to higher quality borrowers will be incentivied under Basel 2. 168 It is not clear whether the present or new Basel Accord are a binding constraint on bank’s current credit operations. Jackson et al (2001, Bank of England WP) suggest that banks may employ more conservative capital standards than those imposed under Basel 1 or likely under Basel 2. Compliance costs are likely to increase. Banks will have to evaluate (as a kind of capital investment decision) whether the costs (including compliance costs) of moving to the more advanced Basel 2 systems are worthwhile. 169 Banks will increasingly target better risk management as a source of competitive advantage. Increasingly, superior risk management will become a ‘key success factor’ for those banks who are able to respond successfully to the new environment. Nevertheless, specialist banks who focus on a smaller number of core products and services should similarly be able to obtain risk management benefits of specialization. 170 Basel 2 will enhance present securitisation trends in banking. This will help in its turn to emphasise further the strategic importance of investment banking. At the same time, lending bankers will face increasing ‘adverse selection’ trends as the better credits are able to access directly the capital markets. This trend will help to re-emphasise the importance of credit skills in lending banks. It will also put pressure on these banks to widen their margins (in order to achieve the higher risk premia needed to cover their more risky lending). 171 Governance will be an increasingly important issue in the new regime. More disclosure is not enough by itself to secure market discipline (the aim of Pillar 3). A wide collection of new and improved governance structures will be needed. These include: a freer market in bank corporate control; good corporate governance in banks; incentive-compatible safety nets; ‘no bail-out’ policies; and proper accounting standards. Banks will be required to disclose more information than ever before to the external market. This will involve additional compliance costs. Strategically, it will reinforce any competitive advantage gained by good risk-management banks. 172 Under Pillar 3 and with likely changes in bank governance arrangements, the prospects of takeovers (and no bail-outs) for individual banks who are ‘inefficient’ are likely to increase. This ‘new world’ is a likely further threat to concepts like mutuality and subsidised (or at least protected from competition) regional banking. Insofar as the new capital regime allows nonbank financial companies a competitive advantage (via lesser capital backing), banks will attempt to alter the balance of competitive advantage through regulatory arbitrage 173 More work is needed on stress testing under Basel 2 and banks can expect further, more detailed efforts from regulators in this area. Already, stress testing appears to be a standard management technique for many banks and most banks that stress test do so at a high frequency (daily or weekly): see Fender and Gibson (Risk, 2001). 174 Perhaps the most fundamental strategic impact of Basel 2 is that it will enhance the SWM (Shareholder Wealth Maximisation) model as the major strategic and managerial model for banks. The essence of this model is its focus on risk and return and the impact of this tradeoff on bank value; the model also emphasises the need for greater risk sensitivity in risk assessments and pricing. Within this model, better risk management is rewarded. 175 Although most of the strategic implications mentioned earlier for retail banks apply also to Spanish savings banks, there are some specific features of the Spanish savings banks that may modify some of these conclusions. These specific features are explored in this section (and summarised in Diagram 1): There have been some recent regulatory actions regarding risk and capital in the Spanish banking system that should be taken into account when defining the threats and opportunities of the new framework for savings banks. The development of a Default Hedging Statistical Fund (the so-called FECI) by the Bank of Spain are two of the recent developments in the regulatory field that impact on the current solvency risk of Spanish savings banks 176 DIAGRAM 1. SPANISH SAVINGS BANKS AND THE NEW REGULATORY CAPITAL FRAMEWORK. KEY FEATURES REGULATION: MARKET DEVELOPMENTS– BASEL2 STRATEGIC IMPLICATIONS SPANISH SAVINGS BANKS AND THE NEW REGULATORY CAPITAL FRAMEWORK CAPITAL REGULATION AND OWNERSHIP SECTORAL PROJECT FOR THE GLOBAL CONTROL OF RISK 177 The establishment of so-called statistical, pro-cyclical or dynamic provisions: Requiring banks to increase these provisions when the business cycle is positive and reducing them during downturns in order to favor intertemporal risk smoothing and loan supply. Basel 2 does not appear to change the view of banking as a pro-cyclical business. Basel 2 could even exacerbate cyclical effects. It is this contingency that has led the Bank of Spain to establish the so-called pro-cyclical or dynamic provisions. The recent lending patterns of the Spanish savings banks are known to reduce these procyclical effects since they have increased credit supply almost linearly over the business cycle. 178 The lending behavior of savings banks has not resulted in higher defaults. On the contrary, default risk management at savings banks has apparently been more efficient than for commercial banks, a fact that may be largely explained by the intertemporal risk smoothing advantages achieved via a close contractual relationship with their customers. 179 There are three main types of “savings-bank” specific effects: (1) those concerning the aim of Basel 2 and the differences between economic and regulatory capital; (2) those that refer to specialisation, size and lending diversification; (3) those related to the implementation of the new capital adequacy requirements, including the sectoral project of Spanish savings banks for the global control of risk. 180 (i) Aim of Basel 2 and Economic and Regulatory Capital Differences While the objective of Stakeholder Wealth Maximisation (STWM) may match more closely the nature of Spanish savings banks, SWM should not be a problem for savings institutions since they have to compete with commercial banks. Nevertheless, the SWM model will be reinforced by Basel 2 and Spanish savings banks may benefit from recent regulatory changes that stress their ownership status as private and non-subsidised. 181 (ii) Size, specialisation and lending diversification Specialist banks (like savings banks) focusing on a smaller number of core products may also be able to obtain the risk management benefits of specialisation. Continuous calibration and capital treatment may reduce the potential loss of competitiveness in retail banking. Servicing, relationship banking and dynamic lending will also be valued positively. 182 (iii) Final implementation of Basel 2 on Spanish savings banks: the sectoral project for the global control of risk The Spanish Confederation of Savings Banks (CECA) has led an ambitious initiative to undertake a sectoral project for the global control of risk. Since this project is oriented to the whole savings bank sector, it has to deal with various problems, like the rigidities of employing a single model for all institutions. However, the project is targetted to provide savings banks with adequate and centralised human and technological resources in order to implement their own model with a high standard of quality. 183 The model for each line of business incorporates risk measurement, control and management operating with three different working groups: information management; organization and procedures; quantitative tools. 184 COMPARATIVE DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS The credit risk of Spanish depository institutions does not seem to be a concern in the short-run. The ratios “doubtful assets/total exposures” and “doubtful loans of other resident sectors/total exposures of resident sectors” have decreased in recent years and are lower than 1% (Table 1). “Statistical” provisions have increased over time as a percentage of total provisions (Table 1). 185 TABLE 1. 186 Source: Bank of Spain (Memory of Bank Supervision 2004) Savings banks and credit co-operatives have enjoyed higher margins compared to commercial banks (Table 2). The margins are in line with the European standards. However, competitive presures have resulted in a decrease of margins over time during the last years. 187 TABLE 2. 188 Source: Bank of Spain (Memory of Bank Supervision 2004) As shown in Table 3, Spanish banks have progressively changed their financial structure to fulfill the requirements of Basel 2. Both Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital have increased significantly in recent years. Banks have increased both the average weight of credit risk exposure and offbalance sheet exposure. 189 TABLE 3. 190 Source: Bank of Spain (Memory of Bank Supervision 2004) Changes in capitalization structure have led to an anticipated fulfillment of Basel 2 requirements (Figure 1a). Tier 1 capital has largely contributed to a reduction in capital requirements, in a context of a significant increase in risk-weighted assets (rise in overall business and Santander’s purchase of Abbey National) (Figure 1b). However, Tier 1 capital has contributed to the growth rate of capital (Figure 1c). Reserves have contributed largely to the growth of Tier 1 capital while the contribution of intangible assets has been negative (Figure 1d). 191 FIGURE 1. SOLVENCY RATIOS OF COMMERCIAL AND SAVINGS BANKS IN SPAIN (1) Source: Bank of Spain (Financial Stability Report, n.8, 2005, May) 192 FIGURE 1. SOLVENCY RATIOS OF COMMERCIAL AND SAVINGS BANKS IN SPAIN (2) Source: Bank of Spain (Financial Stability Report, n.8, 2005, May) 193 Tema 7 EL RIESGO DE TIPO DE INTERÉS: MODELOS DE MADURACIÓN, DE DURACIÓN Y DE “REPRICING” Interest Rate Risk Measurement Repricing or funding gap GAP: the difference between those assets whose interest rates will be repriced or changed over some future period (RSAs) and liabilities whose interest rates will be repriced or changed over some future period (RSLs) Rate Sensitivity the time to reprice an asset or liability a measure of an FI’s exposure to interest rate changes in each maturity “bucket” GAP can be computed for each of an FI’s maturity buckets 195 Calculating GAP for a Maturity Bucket NIIi = (GAP)i Ri = (RSAi - RSLi) Ri where NIIi = change in net interest income in the ith maturity bucket GAPi = dollar size of the gap between the book value of rate-sensitive assets and ratesensitive liabilities in maturity bucket i Ri = change in the level of interest rates impacting assets and liabilities in the ith maturity bucket 196 Simple Bank Balance Sheet and Repricing Gap Assets 1. Cash and due from 2. Short-term consumer loans (1 yr. maturity) 3. Long-term consumer loans (2 yr. maturity) 4. Three-month T-bills 5. Six-month T-notes 6. Three-year T-bonds 7. 10-yr. Fixed-rate mort. 8. 30-yr. Floating-rate m. 9. Premises Liabilities $ 5 50 25 30 35 60 20 40 5 $270 1. Two-year time deposits 2. Demand deposits $ 40 40 3. Passbook Savings 4. Three-month CDs 5. Three-month banker’s acceptances 6. Six-month commercial 7. One-year time deposits 8. Equity capital (fixed) 30 40 20 60 20 20 $270 197 Weakness in the Repricing Model Four major weaknesses it ignores market value effects of interest rate changes it ignores cash flow patterns within a maturity bucket it fails to deal with the problem of rate-insensitive asset and liability cash flow runoffs and prepayments it ignores cash flows from off-balance-sheet activities 198 Duration Model Duration gap - a measure of overall interest rate risk exposure for an FI D = - % in market value of a security R(1 + R) 199 Insolvency Risk Management Net worth a measure of an FI’s capital that is equal to the difference between the market value o its assets and the market value of its liabilities Book Value value of assets and liabilities based on their historical costs Market value or mark-to-market value basis balance sheet values that reflect current rather than historical prices 200 Effects of Changes in Loan Values and Interest Rates on the Balance Sheet Assets Base case Long-term securities Long-term bonds Liabilities $ 80 20 $100 Short-term floating Net worth $ 90 10 $100 After major decline in value of loans Long-term securities Long-term bonds $ 80 8 $88 Liabilities Net worth $90 -2 $88 Liabilities Net worth $90 2 $92 201 After rise in interest rates Long-term securities Long-term loans $ 75 17 $92 The Book Value of Shares The book value of capital usually comprises three components in banking Par value of shares - the face value of the common shares issued by the FI time the number of shares outstanding Surplus value of shares - the difference between the price the public paid for common shares and their par values Retained earnings - the accumulated value of past profits not yet paid in dividends to shareholders Book value of its capital = Par value + Surplus + Retained earnings 202 The Discrepancy between the Market and Book Values of Equity The degree to which the book value of an FI’s capital deviates from its true economic market value depends on a number of values Interest Rate Volatility - the higher the interest rate, the greater the discrepancy Examination and Enforcement - the more frequent the examinations and the stiffer the examiner’s standards, the smaller the discrepancy Loan Trading - the more loans traded the easier to assess the true market value of the loan portfolio 203 Calculating Discrepancy Between Book Values (BV) and Market Values (MV) MV = Market value of equity ownership in shares outstanding Number of shares BV = Par value of equity + Surplus value + Retained earnings + Loan loss reserves Number of shares Market-to-book ratio A ratio that shows the discrepancy between the stock market value of an FI’s equity and the book value of its equity 204 Central Bank & Interest Rate Risk Federal Reserve Bank: U.S. central bank Open market operations influence money supply, inflation, and interest rates Oct-1979 to Oct-1982, nonborrowed reserves target regime – did not work Implications of reserves target policy: Increases importance of measuring and managing interest rate risk. Effects of interest rate targeting. Lessens interest rate risk Greenspan view: Risk Management Focus on Federal Funds Rate Simple announcement of Fed Funds increase, decrease, or no change. 205 Repricing Model Repricing or funding gap model based on book value. Contrasts with market value-based maturity and duration models recommended by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). Rate sensitivity means time to repricing. Repricing gap is the difference between the rate sensitivity of each asset and the rate sensitivity of each liability: RSA - RSL. Refinancing risk 206 Maturity Buckets Commercial banks must report repricing gaps for assets and liabilities with maturities of: One day. More than one day to three months. More than 3 three months to six months. More than six months to twelve months. More than one year to five years. Over five years. 207 Repricing Gap Example Assets 1-day $ 20 >1day-3mos. 30 >3mos.-6mos. 70 >6mos.-12mos. 90 >1yr.-5yrs. 40 >5 years 10 Liabilities Gap Cum. Gap $ 30 $-10 $-10 40 -10 -20 85 -15 -35 70 +20 -15 30 +10 -5 5 +5 0 208 Repricing Gap Dollar GAP Positive Negative Spread Effect Positive R Increase Direction of NII Increase Negative Increase Ambiguous Positive Decrease Ambiguous Negative Decrease Decrease Positive Increase Ambiguous Negative Increase Decrease Positive Decrease Increase Negative Decrease Ambiguous 209 Applying the Repricing Model NIIi = (GAPi) Ri = (RSAi - RSLi) ri Example: In the one day bucket, gap is -$10 million. If rates rise by 1%, NII(1) = (-$10 million) × .01 = -$100,000. 210 Restructuring Assets & Liabilities The FI can restructure its assets and liabilities, on or off the balance sheet, to benefit from projected interest rate changes. Positive gap: increase in rates increases NII Negative gap: decrease in rates increases NII Example: State Street Boston Good luck? Or Good Management? 211 Repricing Model Problems with model: measures only short-term profit changes not shareholder wealth changes maturity buckets are arbitrarily chosen assets and liabilities within a bucket are considered equally rate sensitive ignores runoffs ignores prepayments 212 The Maturity Model Explicitly incorporates market value effects. For fixed-income assets and liabilities: Rise (fall) in interest rates leads to fall (rise) in market price. The longer the maturity, the greater the effect of interest rate changes on market price. Fall in value of longer-term securities increases at diminishing rate for given increase in interest rates. 213 Maturity Model Leverage also affects ability to eliminate interest rate risk using maturity model Example: Assets: $100 million in one-year 10-percent bonds, funded with $90 million in one-year 10-percent deposits (and equity) Maturity gap is zero but exposure to interest rate risk is not zero. 214 Duration Duration Weighted average time to maturity using the relative present values of the cash flows as weights. Combines the effects of differences in coupon rates and differences in maturity. Based on elasticity of bond price with respect to interest rate. 215 Duration and Duration Gap market-value based model for managing interest rate risk more accurate measures of interest rate risk exposure than simple maturity model duration gap considers market values and maturity distributions of assets and liabilities unlike repricing model duration measures average life of asset or liability has economic meaning of interest sensitivity of that asset’s or liability’s value 216 Duration Duration D = Snt=1[CFt• t/(1+R)t]/ Snt=1 [CFt/(1+R)t] Where D = duration t = number of periods in the future CFt = cash flow to be delivered in t periods n= term-to-maturity R = yield to maturity. 217 Duration Gap duration of asset portfolio or liability portfolio is just weighted-average duration of each individual asset or liability also the accounting identity holds A = L + E or E = A - L when rates change, the change in the equity or net worth is equal to the difference between the change in the MV of the assets and liabilities instead of how we used maturity model, here we want to relate sensitivity of net worth to its duration mismatch instead of its maturity mismatch because duration is a more accurate measure of interest rate sensitivity 218 Duration Gap assuming similar rate changes for assets and liabilities Duration Gap Positive Negative Interest Rate Change Increase Decrease Biggest Value Change Assets Assets Equity Value Decreases Increases Increase Decrease Liabilities Liabilities Increases Decreases 219 Tema 8 EL RIESGO DE MERCADO Trading Risks Trading exposes banks to risks 1995 Barings Bank 1996 Sumitomo Corp. lost $2.6 billion in commodity futures trading 1997 market volatility in Eastern Europe and Asia 1998 continuation with Russian bonds AllFirst/ Allied Irish $691 million loss Partly preventable with software Rusnak currently serving 7 ½ year sentence for fraud Allfirst sold to Buffalo based M&T Bank 221 Implications Emphasizes importance of: Measurement of exposure Control mechanisms for direct market risk—and employee created risks Hedging mechanisms 222 Market Risk Market risk is the uncertainty resulting from changes in market prices . Affected by other risks such as interest rate risk and FX (foreign exchange) risk It can be measured over periods as short as one day. Usually measured in terms of dollar exposure amount or as a relative amount against some benchmark. 223 Market Risk Measurement Important in terms of: Management information Setting limits Resource allocation (risk/return tradeoff) Performance evaluation Regulation BIS and Fed regulate market risk via capital requirements leading to potential for overpricing of risks Allowances for use of internal models to calculate capital requirements 224 Calculating Market Risk Exposure Generally concerned with estimated potential loss under adverse circumstances. Three major approaches of measurement JPM RiskMetrics (or variance/covariance approach) Historic or Back Simulation Monte Carlo Simulation 225 JP Morgan RiskMetrics Model Idea is to determine the daily earnings at risk = dollar value of position × price sensitivity × potential adverse move in yield or, DEAR = Dollar market value of position × Price volatility. Can be stated as (-MD) × adverse daily yield move where, MD = D/(1+R) Modified duration = MacAulay duration/(1+R) 226 Confidence Intervals If we assume that changes in the yield are normally distributed, we can construct confidence intervals around the projected DEAR. (Other distributions can be accommodated but normal is generally sufficient). Assuming normality, 90% of the time the disturbance will be within 1.65 standard deviations of the mean. 227 Historic or Back Simulation Advantages: Simplicity Does not require normal distribution of returns (which is a critical assumption for RiskMetrics) Does not need correlations or standard deviations of individual asset returns. 228 Historic or Back Simulation Basic idea: Revalue portfolio based on actual prices (returns) on the assets that existed yesterday, the day before, etc. (usually previous 500 days). Then calculate 5% worst-case (25th lowest value of 500 days) outcomes. Only 5% of the outcomes were lower. 229 Estimation of VAR: Example Convert today’s FX positions into dollar equivalents at today’s FX rates. Measure sensitivity of each position Calculate its delta. Measure risk Actual percentage changes in FX rates for each of past 500 days. Rank days by risk from worst to best. 230 Weaknesses Disadvantage: 500 observations is not very many from statistical standpoint. Increasing number of observations by going back further in time is not desirable. Could weight recent observations more heavily and go further back. 231 Monte Carlo Simulation To overcome problem of limited number of observations, synthesize additional observations. Perhaps 10,000 real and synthetic observations. Employ historic covariance matrix and random number generator to synthesize observations. Objective is to replicate the distribution of observed outcomes with synthetic data. 232 Regulatory Models BIS (including Federal Reserve) approach: Market risk may be calculated using standard BIS model. Specific risk charge. General market risk charge. Offsets. Subject to regulatory permission, large banks may be allowed to use their internal models as the basis for determining capital requirements. 233 BIS Model Specific risk charge: Risk weights × absolute dollar values of long and short positions General market risk charge: reflect modified durations expected interest rate shocks for each maturity Vertical offsets: Adjust for basis risk Horizontal offsets within/between time zones 234 Tema 9 EL RIESGO DE LIQUIDEZ Causes of Liquidity Risk Two types of liquidity risk: when depositors or insurance policyholders seek to cash in or withdraw their financial claims when OBS commitments are exercised Fire-sale price the price received for an asset that has to be liquidated (sold) immediately 236 Liability Side Liquidity Risk Core deposits deposits that provide a relatively stable, long-term funding source to a bank Net deposit drains the amount by which cash withdrawals exceed additions; a net cash outflow can be managed two ways: purchased liquidity management stored liquidity management (continued) 237 Liability Side Liquidity Risk Purchased liquidity federal funds market repurchased (repo) agreement market issue additional fixed-maturity CD’s, notes, and/or bonds Stored liquidity can use or sell off some of it’s assets (such as Tbills) utilize its stored liquidity (i.e., cash in vault) 238 Measuring a Bank’s Liquidity Exposure Net liquidity statement measures liquidity position by listing sources and uses of liquidity Peer group ratio comparisons a comparison of its key ratios and balance sheet features with those for banks of a similar size and geographic location Liquidity index measures the potential losses an FI could suffer from a sudden or fire-sale disposal of assets compared to the amount it would receive at a fair market value established under normal market conditions 239 Calculation of the Liquidity Index N I = [(wi)(Pi / Pi*)] i=1 where wi = Percentage of each asset in the FI’s portfolio wi = 1 240 Financing Gap and the Financing Requirement Financing gap the difference between a bank’s average loans and average (core) deposits if the financing gap is positive, the bank must fund it by using its cash and liquid assets and/or borrowing funds in the money market Financing requirement the financing gap plus a bank’s liquid assets the larger a bank’s financing gap and liquid asset holdings, the higher the amount of funds it needs to borrow on the money markets and the greater is its exposure to liquidity problems 241 Liquidity Planning Allows managers to make important borrowing priority decisions Components of a liquidity plan delineation of managerial details and responsibilities detailed list of fund providers most likely to withdraw and the pattern of fund withdrawals identification of the size of potential deposit and fund withdrawals over various time horizons in the future sets internal limits on separate subsidiaries and branches borrowing and bounds for acceptable risk premiums to pay details a sequencing of assets for disposal 242 Deposit Drains and Bank Run Liquidity Risk Deposit drains may occur for a variety of reasons concerns about a bank’s solvency failure of a related bank sudden changes in investor preferences Bank run a sudden and unexpected increase in deposit withdrawals from a bank Bank panic a systemic or contagious run on the deposits of the banking industry as a whole 243 Deposit Insurance and Discount Window Deposits insured for $100,000 Federal Reserve provides a discount window facility to meet banks’ short-term nonpermanent liquidity needs loans made by discounting short-term high-quality securities such as T-bills and banker’s acceptances with central bank leads to increased monitoring from the Federal Reserve which acts as a disincentive for banks to use for ‘cheap’ funding 244 Liquidity Risk and Insurance Companies Early cancellation of a life insurance policy results in the insurer having to pay the surrender value the amount that an insurance policyholder receives when cashing in a policy early when premium income is insufficient to meet surrenders, the insurer can sell liquid assets such as government bonds Property-Casualty PC insurers have greater need for liquidity due to uncertainty so ten to hold shorter term assets Guarantee Programs for Life and PC Insurance Co. 245 Liquidity Risk and Mutual Funds Open-end mutual funds must stand ready to buy back issued shares from investors at their current market price or net asset value If a mutual fund is closed and liquidated, the assets would be distributed on a pro rata basis 246