Yanomami Indians

advertisement

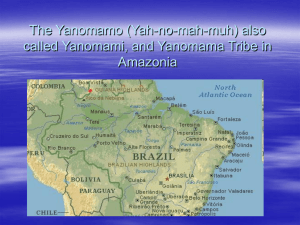

Yanomami Indians 'Yanomami' means 'Human Being' The Yanomami are an indigenous tribe (also called Yanamamo, Yanomam, and Sanuma) made up of four subdivisions of Indians which live in the tropical rain forest of Southern Venezuela and Northern Brazil. Each subdivision has its own language. They include the Sanema which live in the Northern Sector, the Ninam which live in the southeastern sector, the Yanomam which live in the southeastern part and the Yanomamo which live in the southwestern part of Yanomami area. Of the approximately 20,000 Yanomami alive today, about 12,000 of these are Yanomamo. Yanomami Territory Villages The Yanomami live in about hundreds of small villages, grouped by families in one large communal dwelling called a Shabono; this disc-shaped structure with an open-air central plaza is an earthly version of their gods' abode. They hunt and fish over a wide range and tend gardens in harmony with the forest. Villages are autonomous but constantly will interact with each other. The villages, which contain between 40 and 300 individuals, are scattered thinly throughout the Amazon Forest. The distance between villages may vary from a few hours walk to a ten day walk. Shabono Approximately 120 meters across Warfare Though many Yanomami are peace, many are fierce warriors. Sometimes their warring is to capture women, so that their best warriors can maximize their reproductive success. In general, warring villages are usually several days walk from each other, where as tranquil ones may be less than a day. Villages will usually fission when the population reaches 100 to 150 people but in times of warfare villages will not split before they reach a population of around 300 individuals. Villages may go to war for a number of reasons and warfare makes up a large part of Yanomami life. About 40% of adult males have killed another person and about 25% of adult males will die from some form of violence. Violence will vary from chest pounding, in which opponents take turns hitting each others on the chest, to club fights, to raids which may involve the killing of individuals and abducting the women, to all out warfare. Warriors Spiritual Beliefs The Yanomami people's traditions are shaped by the belief that the natural and spiritual world are a unified force; nature creates everything, and is sacred. They believe that their fate, and the fate of all people, is inescapably linked to the fate of the environment; with its destruction, humanity is committing suicide. Their spiritual leader is a shaman. Marriage Marriage arrangements are not only vital in forging alliances but keeping the peace between families as well. Most women have prearranged marriages and marry at a young age. The preferred marriage is the "bilateral cross-cousin marriage" which helps produce strong relationships between families and villages. Families Forest People (Hunters) - River People (Fishing) Today about 95% of the Yanomami live deep within the Amazon forest as compared to the 5% who live along the major rivers. Compared to the "forest people," the "river people" are much more sedentary and subsist by fishing and trading goods such as canoes and hooks with other villages. The "forest people" are horticulturists as well as hunters and gathers. Gardens They will spend up to two hours of their day "garden farming" which is quite a labor intensive process. Some of the crops grown include sweet potatoes, bananas, sugar cane and tobacco. However as horticulturists the Yanomami do not get sufficient protein from their crops. Therefore the Yanomami will spend as much as 60% of their time trekking. Men usually make up the hunters and the women the gathers. Men will go on long distant hunts that may last up to a week. The fact that just about all of the Yanomami live deep within the forest has been quite significant for their survival. Since most outsiders have invaded the Amazon via the large rivers, the Yanomami have been able to live in isolation until very recently. Because of this they have been able to retain their culture and their identity which many Indians of the Amazon have lost. 1980's - The Gold Rush The Yanomami had very little contact with the outside world until the 1980's. Since 1987, the Yanomami have seen about 10% of their entire population - over 2,000 people - decimated by massacres and diseases brought by invaders. The Yanomamo is the most well known and best documented of the four division partly because they have been victims of a recent gold rush. After gold was discovered on Yanomami land in the mid-1980's, thousands of miners illegally rushed into the territory. The constant flights of supply planes and the noise from generators and pumps used in the mining operation has frightened away the game animals the Indians rely on as a key source of protein in their diet. High pressure hoses are used to wash away river banks, silting the rivers and destroying spawning grounds. Problems Mercury is used to separate the gold from soil and rock. It is then dumped in the rivers haphazardly. Mercury bio-accumulates and reeks havoc on the entire ecosystem. The effects of mercury poisoning reach even the surrounding trees, some of which rely on birds and fish to disperse their seeds. The mercury ascends the food chain up to the Yanomami in the form of a neurotoxin that especially affects child development. The most devastating statistic of them all: child mortality rates have skyrocketed while birth rates have declined. Government Involvement In 1992, the Yanomami Territory was demarcated and ratified, yet the government has not consistently kept its commitment to protect their land. Supported by politicians and business people, the gold miners assault escalated. In July 1993, a group of miners tried to exterminate the village of Haximu, killing 16 Yanomami, in what Brazilian Attorney General Aristides Junqueira classified as genocide. Despite international outcry spurred by the massacre, miners continue to enter the territory illegally. According to the Commission for the Creation of the Yanomami Park (CCPY) in Sao Paulo and the Indianist Missionary Council (CIMI) in Brasilia, state and local politicians are fighting to reduce the Yanomami territory because they want access to its rich mineral deposits. There is little question that if this happens, the gold prospectors will be replaced by large scale commercial mining operations that will only compound the devastation of the Yanomami and the rainforest. Other Problems In the 1960s anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon’s accounts of his life among Venezuela’s Yanomami Indians made them— and him—famous. By the early 1990s, however, a growing number of critics were charging him with misconduct, and protests from government officials and activists made it impossible for him to secure a permit to Venezuela after 1993. Darkness in El Dorado The charges stemmed from Chagnon’s allegedly culturedestroying practice of exchanging trade goods such as machetes with the Yanomami for delicate cultural information, including family genealogies (the Yanomami consider it taboo to speak of the dead). In 2000 native-rights activist Patrick Tierney detailed the anti-Chagnon case in his book Darkness in El Dorado. Just days after it was published, the Venezuelan government sealed off Yanomami territory to outside journalists, researchers, and scientists; banned Chagnon from the region; and began their own investigation into the conditions of the Yanomami and the supposed damage done by outsiders. AA findings The American Anthropological Association released the final report of a panel charged with reviewing accusations of unethical behavior by prominent anthropologists who studied the Yanomami people in the Amazon River basin in the late 1960s. Alongside its factual dissections, in which it criticizes both the accused anthropologists and their accuser, the 304-page report contains reflective essays that are intended to improve ethical practices among anthropologists who work with indigenous communities. Patrick Tierney's 2000 book, Darkness in El Dorado, (W.W. Norton) revolved around anthropologists' work among the Yanomami, an indigenous ethnic group in remote areas of Brazil and Venezuela. Mr. Tierney charged that during the late 1960s, Napoleon Chagnon, now a professor emeritus of anthropology at the University of California at Santa Barbara, and the late James V. Neel, a longtime professor of human genetics at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, had recklessly endangered the communities they studied. Continued Among the most serious accusations: that Mr. Chagnon had subtly encouraged murderous violence among the Yanomami, and that Mr. Neel's efforts to administer measles vaccines among the Yanomami were driven more by scientific curiosity than by sound medical practice. Critics of Mr. Tierney's book have strongly denied these charges, and two previous reports -- by the American Society of Human Genetics and the University of California at Santa Barbara -- have found the accusations to be unwarranted. In a short preface to the report, the association's executive board declares that Mr. Tierney's book "contains numerous unfounded, misrepresented, and sensationalistic accusations about the conduct of anthropology among the Yanomami." But the report also says that the book, though "deeply flawed ... [presents] ethical issues that we must confront."