Practice 1 Sheroanawë Hakihiiwë: Recent Projects Studio Research

advertisement

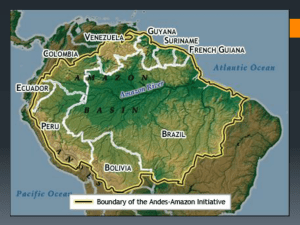

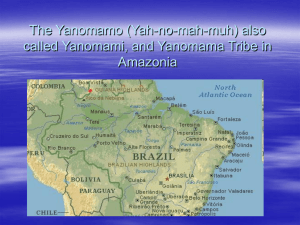

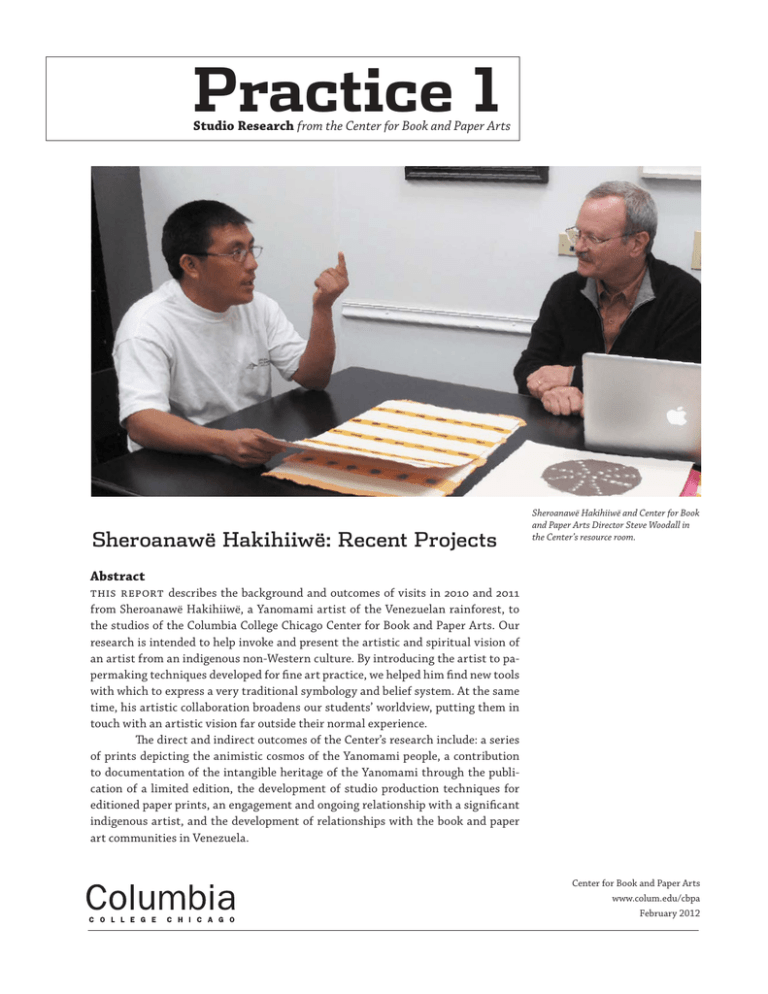

Practice 1 Studio Research from the Center for Book and Paper Arts Sheroanawë Hakihiiwë: Recent Projects Sheroanawë Hakihiiwë and Center for Book and Paper Arts Director Steve Woodall in the Center’s resource room. Abstract This report describes the background and outcomes of visits in 2010 and 2011 from Sheroanawë Hakihiiwë, a Yanomami artist of the Venezuelan rainforest, to the studios of the Columbia College Chicago Center for Book and Paper Arts. Our research is intended to help invoke and present the artistic and spiritual vision of an artist from an indigenous non-Western culture. By introducing the artist to papermaking techniques developed for fine art practice, we helped him find new tools with which to express a very traditional symbology and belief system. At the same time, his artistic collaboration broadens our students’ worldview, putting them in touch with an artistic vision far outside their normal experience. The direct and indirect outcomes of the Center’s research include: a series of prints depicting the animistic cosmos of the Yanomami people, a contribution to documentation of the intangible heritage of the Yanomami through the publication of a limited edition, the development of studio production techniques for editioned paper prints, an engagement and ongoing relationship with a significant indigenous artist, and the development of relationships with the book and paper art communities in Venezuela. Center for Book and Paper Arts www.colum.edu/cbpa February 2012 A Collaboration Begins In early 2010, the Center for Book & Paper Arts featured artist Laura Anderson Barbata in a retrospective exhibition of her work, Among Tender Roots. Barbata is an interdisciplinary artist whose work ranges from costume design to sculpture and video, but the exhibition highlighted another important aspect of her work: the intersection of social action with artistic practice, with particular attention to her projects in hand papermaking. The centerpiece of the exhibition was her Yanomami Owë Mamotima project. Founded in 1992, the project established a permanent hand papermaking facility in the Yanomami community of Platanal, Venezuela. Their first editioned publication, Shapono (meaning a communal house) transcribes a traditional creation myth and tells the story of the community’s first shapono. Though carved printing blocks had long been a part of their culture, these blocks were used exclusively for body decoration. The use of a new substrate, paper, as a matrix for this ceremonial art merged two technologies to create what is essentially a new art form. In 2000, the first book, Shapono, received the Best Book of the Year award from Melissa Potter couches a sheet of paper and Sheroanawë Hakihiiwë stencils pigmented pulp onto a base sheet. the Centro Nacional del Libro of Venezuela, and Barbata’s project has helped inspire Caracas-based Instituto de Estudios Avanzados (IDEA), led by Professor Alvaro Gonzalez Bastidas, to build the Shapono School in Alto Orinoco to preserve and promote Yanomami culture. Among Tender Roots was the first exhibition to feature Shapono in the United States. Inspired by this fact, Bastidas arranged for Sheroanawë Hakihiiwë, Yanomami Owë Mamotima project leader and artist, to travel with IDEA representative Maria Elena Ghersi to offer a lecture at Columbia College Chicago. In order to maximize this extraordinary opportunity, I proposed that we create with the artist an edition of fifteen, 22 x 30 inch works in handmade paper at the Center, aided by graduate students. The small edition was such a success that faculty and staff committed to bringing Hakihiiwë back the following year. In its second iteration, Hakihiiwë worked with my Intermediate Papermaking students to produce a pulp painting edition-variable of six of his paintings depicting traditional Yanomami stories he had collected from his mother. (In a video interview, Haki- hiiwë described the tradition of women as artists in Yanomami culture, which developed from women painting onoto root on babies in elaborate patterns to enhance their immune systems.) The project continued in the summer of 2011 with an innovative artistic model conceived by Gonzalez and esteemed curator Tahia Rivero of Fundación Mercantil in Caracas. Supported by the Taller de Artes Gráficas (TAGA) and IDEA, ten of Venezuela’s top visual artists were hand selected by Rivero for a four-week intensive workshop to create a collaborative artists’ book. The workshop challenged the roles of paper and book in contemporary artmaking practice by engaging the selected artists with media they had never used before. The book was made with sisal, daphne, and cotton handmade paper produced by the artists, and featured the artists’ creative interpretations of the Yanomami story Pore Awë (Pore Awë means Plaintain Man and the story tells of the Spanish introducing the staple crop to the Yanomami people). Columbia College Book and Paper graduate students Haley Nagy and Maggie Puckett worked with me to teach hand papermaking and develop an innovative book structure to embody the spirit of the story. It was an intense experiment in the collaborative process, and the artists spent long hours discussing the boundary between community and individual artistic engagement in the project. The final work was featured in an exhibition at G (18) Centro De Artes Los Galpones, Caracas, Venezuela; sales proceeds will benefit the Yanomami community. Our plans for the future include bringing Hakihiiwë back to the papermaking studio to produce a third series of works that engage his drawings with fibers from his community. A second iteration of the book, paper, and printmaking collaboration is planned to take place in Caracas next summer. We hope to one day teach hand papermaking and book arts at the Shapono School in Platanal to continue this remarkable exchange of artistic interpretation between these diverse cultures. In the spirit of collaboration, we challenge our impressions, engage cultures urgently in need of preservation, and bring light to our shared human experience. Melissa Potter Book and Paper grad students Hannah King and Boo Gilder pull base sheets for the project. Melissa Potter and Clifton Meador with students Claire Sammons, Boo Gilder and Laura Miller. Caracas, you watermarked my life The group of artists, CCC students, faculty, curator, and organizers in Caracas. I SPENT a month in Caracas, Venezuela in the summer of 2011, participating in a book and paper workshop to support the renewal of the Yanomami tribe. I arrived in the capital along with papermaking instructor Melissa Potter, fellow MFA student Haley Nagy, and Yanomami artist Sheroanawë Hakihiiwë (returning from his collaboration with Columbia College Book and Paper students). The talented and energetic Alvaro Gonzalez, with the help of his tireless interns (Jesus Eduardo Gonzalez Rodriguez, and a man who went by the politically incorrect moniker Chino) constructed a fully functioning papermaking studio in the backyard of the a well-equipped printmaking workshop, El Taller de Artistas Gráficos Asociados (TAGA). Under the protective canopy of trees, and the watchful eyes of parrots, we were joined by local artists (Natalya Critchley, Emilio Narciso, Leonardo Nieves, Suwon Lee, Juan José Olavarría, Luis Romero, Agustín Villasana) and charged with the task of developing a book of artistic responses to the Yanomami myth Pore Awë. Together we prepared daphne and sisal for papermaking by cutting, soaking, cooking, and finally beating the fibers in a Mark Lander Critter paper beater. Some fiber was dyed with turmeric and achiote to produce bright yellow-orange pulp. Maggie Puckett, in Venezuela, making a Sheets were formed with moulds and deckles and deckle boxes (all construct‘blowout’ stencil in handmade paper. ed by Alvaro Gonzalez and his team) and dried on metal sheets in a room semi-sealed from the humid climate. Dehumidifiers greatly decreased the drying time, but also caused a couple of power outages. For the next few weeks the artists each worked to produce an edition of 25 artworks using handmade paper, lithography, etching, cutting, collage, wax, ashes, dirt and whatever else each artist had in their arsenal. The day before we left Caracas, an exhibition of the first two completed books was held at the Centro de Arte Los Galpones in Caracas. Along with the book, the exhibition featured documentation by photographer Ricardo Jiménez and printing plates used by the artists to illuminate the month-long process. While Caracas is known for violence and complicated politics, my hosts, instructors, and collaborators showed me unlimited generosity and warmth, revealing a more enchanting side of this deeply beautiful, but deeply troubled land. I am honored to have been part of this exciting and noble workshop, and I look forward to future manifestations of this international collaboration. Maggie Puckett Among Tender Roots Few artists have combined community action with an art practice as effectively as Laura Anderson Barbata. Traditionally educated in art, and highly successful in mainstream gallery and museum networks, her career evolved quickly to incorporate her passion for art with a social purpose. Among Tender Roots highlights this aspect of Barbata’s career, with focus on hand papermaking as a community practice. Barbata employs all aspects of hand papermaking in these undertakings: recycling, science, education, and perhaps above all the primacy of papermaking as a locally available art medium. In 1992, Barbata entered Venezuelan Yanomami territory on the pretext of studying the tribe’s distinctive canoe building technique for use in her sculptural work, but also to satisfy an abiding interest in the cultural and environmental ecologies of artmaking. In exchange for learning canoe building, she taught them hand papermaking, and the Yanomami Owë Mamotima (meaning, roughly, “Yanomami working together to make paper”) project was born. The project has evolved to incorporate the first self-written and printed history by a native people of the Amazon region, and at the same time has created a revenue stream intended to keep the local cultural and ecological environment intact. Yanomami use the paper for prints, cards and illustrated books, which tell stories of their society’s formidable struggle to balance tradition and culture with technological advancement and the threat of environmental devastation. Their books represent a significant achievement: true artists’ books created in one of the most remote inhabited regions on the planet. The publication Shapono tells the story of how twin brothers Omawë and Yoawë built the first shapono, or communal dwelling. The book is illustrated in relief prints by children of their community and is the culture’s first written record. Their second book, Iwariwë, relates a trickster-as-culture-hero myth, and was created as a single-copy artists’ book, with a companion offset-printed trade edition published by the IDEA Institute in Caracas. Locally available fibers for hand papermaking create distinction by location, and the range of fibers available for Yanomami Owë Mamotima attests to the astounding biodiversity and specificity of the rainforest. As a support for the hand carvings and stories of the indigenous peoples of this region, the literal use of the forest for paper lends depth and power to Yanomami prints and text. It is a mistake, however, to assume papermaking produces beautiful art with ease. Those familiar with handmade paper understand that it can be among the most challenging media, leaning towards rather unaesthetic mush if not handled with the utmost finesse and sensitivity to local alchemies. And this is where Barbata is a master on many levels. An interdisciplinary artist whose work ranges from costume design to sculpture and video, her hand is evident in the direction of all these projects. She has an unusual ability to encourage both excellence and authentic local expression at the same time. Perhaps the most impressive aspect of Yanomami Owë Mamotima has been its tremendous achievement in self-sustainability. Unlike many artistic initiatives whose initial efforts in social engagement are exhausted after the review buzz dies down, Barbata’s projects enjoy ongoing success and have found recognition beyond the fine art community. Much of this can be attributed to the holistic approach these programs employ, as well as community buy-in that allows Barbata to act as an ongoing consultant even as the projects Sheroanawë stencils pigmented pulp. Laura Anderson Barbata curating wet sheets. Sheroanawë and CCC graduate student Trisha Martin. operate independently. Yanomami Owë Mamotima has been sustained for nearly twenty years, a monumental accomplishment. Yanomami participants in the project also lead workshops for neighboring communities, and the project’s success has created new visibility overall for indigenous communities in Venezuela. Barbata’s unique blend of artistic vision, community involvement, education, and local empowerment highlights an advantage of hand papermaking as a medium for flexible integration of art and activism. The self-sustainability papermaking affords through locally available and recycled materials, combined with its relative ease of use as an artistic medium, can bring forth unexpected outcomes. The planned Shapono School, with its permanent studio and community center in Yanomami territory, could not have happened without Barbata’s pioneering work. And her work continues to evolve, introducing new ideas and materials to both community activism and her own studio practice. The success and momentum generated by these projects will surely continue to inspire more to follow. Melissa Potter Laura Anderson Barbata Working With Shero It was in 1992 that I first went to the Amazon of Venezuela. I was interested in exploring the ways in which my art-making practice could address environmental and social concerns in a participatory/collaborative manner. Upon arriving in Mahekoto-Platanal, a small Yanomami community located along the Orinoco River, I was met by a group of Yanomami youth with whom I was unable to communicate. Having focused a great deal of my studio work on drawing, I firmly believed in the capacity that this medium has to convey complex ideas and emotions. I thought that drawing could be our common language. I was wrong. I had a journal made with handmade paper and tore out sheets, which I shared along with some pencils. I was the only one who drew on the paper, while everyone else had different uses for it. One used the point of the pencil to pierce a small hole into a corner of the sheet and threaded a long, thin fiber through it, creating a type of kite. Another carefully folded it lengthwise several times like a fan and tucked it into his loincloth. Someone else raised it against the sunlight to examine it and pointed to trees and plants that surrounded us. A fourth brought it toward her face and took a deep breath. Their reactions were not so unconventional, however. In fact, I had often seen experienced papermakers interact with hand-made paper in exactly the same way. I understood immediately that I was in the company of extraordinary papermakers who had never seen hand-made paper before. And so the project began. Yanomami culture has a rich oral tradition of storytelling that has been challenged over the last fifty years as their youth have been taught by missionaries to read and write. There were a few books in the Amazon for the Yanomami community—some in Spanish and others in Yanomami—but none written by the Yanomami themselves. I felt that here was an opportunity to balance the outflux and influx of information, and that this could be achieved by refocusing, reorganizing and reconceptualizing local technology and materials towards the creation of books made by hand by the local Yanomami community. After I presented a self-sustaining paper and bookmaking project to the community of Mahekoto Platanal, it was quickly embraced by the village. A group of papermakers, printers, bookmakers, narrators, and Pulp painting in progress scholars began to form with the assistance of the shaman. The group was in constant flux—some days with many participants and others with very few. There was always a member of Sheroanawë Hakihiiwë´s family with us. The workshops were open to anyone in the community and thus frequently crowded. We began to test local fibers normally harvested by the community to see their response to both Western and Japanese papermaking techniques. We shared our findings with Dieu Donné Papermill experts Mina Takahashi and Melissa H. Potter (Potter worked at Dieu Donné prior to Columbia College Chicago), who from the start were generous advisors to the project. Clayton Kirking, the chief librarian for the Gimbel Library at the Parsons Patterns representing a mythic caterpillar School in New York, was also an invaluable resource. Community protocol dictates that the chief or Capitán of the community must choose the leaders of any project. In this case the Capitán named himself head of the Yanomami Owë Mamotima project, which helped us gain the community’s respect for and interest in the papermaking project. Unfortunately, he was not really invested in becoming a papermaker and quickly lost interest, so participation and output began to shrink. Sheroanawë´s family was very concerned and spoke to me about the risk of losing the project due to lack of leadership and community involvement. It was at this time that I discovered who was behind the great support shown by this family—it was the head of the household, who from the first day recognized the importance and value of this project and urged her children to learn and master the art of paper and book making. Sheroanawë wanted to lead the project to ensure that it continued, but protocol made it impossible for him to assume this position. At his recommendation, I discussed the situation with the community and he was soon elected publicly to lead the project. Shortly thereafter, Shapono, the first book created by and in the Yanomami territory, was completed and received the Best Book of the Year Award in Venezuela. It was the first major recognition for the Yanomami and for all indigenous people of Venezuela. Today, Shapono (edition of fifty signed copies) is part of major collections around the world. Sheroanawë has been leading the project since 1996 and with his family is developing a strategic plan for its growth. His mother is a spokesperson for the project in the community and an important advisor on pigments, fibers, and other traditional knowledge that can be translated into papermaking techniques. She also conveys important traditional narratives for inclusion in the books. Not only has she been pivotal in the growth and stability of this project, she continues to be an integral part of it to this day. With strong family and community support, recognition from government institutions such as IDEA, and the international papermaking community, Sheroanawë began to solidify his career as a papermaker. As an artist, he quickly gained the confidence to explore a more complex visual language. It was not until he was invited by Columbia College Chicago’s Center for Book and Paper Arts to participate in their artist residency program held in conjunction with my show Among Tender Roots, however, that Sheroanawë was able to establish himself firmly in the contemporary art circuit of Venezuela. Today he is recognized as a contemporary artist and his work is included in various collections both private and public, among them the Colección de Arte Contemporaneo Banco Mercantil, Caracas, Venezuela. Laura Anderson Barbata Participants Melissa Potter Assistant Professor Columbia College Chicago Interdisciplinary MFA in Book and Paper Haley Nagy MFA Candidate Columbia College Chicago Interdisciplinary MFA in Book and Paper Maggie Puckett Alumna Columbia College Chicago Interdisciplinary MFA in Book and Paper Laura Anderson Barbata Artist Associate Professor, La Esmeralda, INBA., Mexico, D.F. , Mexico Venezuela project concept/support Alvaro Gonzalez Bastidas Maria Elena Ghersi Venezuela participants Natalya Critchley Sheroanawë Hakihiiwë Ricardo Jiménez Suwon Lee Norma Morales Leonardo Nieves Emilio Narciso Juan José Olavarria Gaby Quero Tahía Rivero Luis Romero Augustin Villasana Gallery of works by Hakihiiwë, created with the aid of Melissa Potter, Laura Anderson Barbata, and Book and Paper MFA students in the paper studios at the Center for Book and Paper Arts. The images represent, in his words, (top) a large edible snake associated with festivals; (middle) the protective spirit of a small jaguar; (bottom) food washing baskets. For more images, go online to http://www.colum.edu/Academics/interarts//book-and-paper.