Higher Social Anthropology Yanomamo Presentation

advertisement

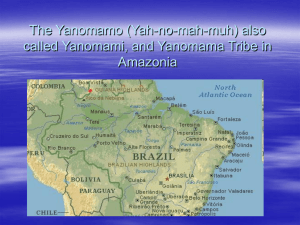

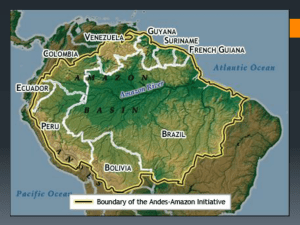

Higher Social Anthropology Yanomamo Presentation Handouts Warfare and Politics Reasons for warfare Stealing coveted items e.g. women, tobacco & peaches Bad history between tribes & revenge Death of a baby blamed on the neighbouring tribes shaman. Controlling the population Stages of war Member within the tribe will fight each other. This starts with chest bounding (not causing external bleeding). This then escalates to stabbing, and out of control fighting. They then raid a village. Their aim is to raid the village, kill the headmen and steal the wives. If 1 of the raiders is killed the raid is a failure. War facts Before raiding other villages they perform a ritual. They sing to the enemy and symbolically eat their flesh, which they then vomit. To find the enemy they shout into the forest and listen for the echoes to find where they are. Nomohori is a taboo for the Yanomamo. This is when the raiders trick the enemy and kill them whilst distracted. Headman There is one headman of the village. His role is to keep control of the village and any fighting, as well as leading the tribe into war. They are most likely to be killed, so it is therefore an unpopular job. The headman will be an Unokais. This is a man who has killed another person. They have prestige over other men and usually have 3 times more men. Women Women do not have a say in the Yanomamo politics. Women also do not participate in any of the fighting. They are the prize of raids, raped and even traded with other villages. If a women is caught cheating on her husband part of her ear of buttock will be cut off. Other Facts One village will always have a good alliance with the closest neighbouring village, but will have many more enemies. These tribes will sometimes have a feast, where the men perform dances and rituals to display their aggression and power. The feast ends with the two tribes attacking an enemy tribe. Yanomamö Religion and Belief The Yanomamö believe that the world is separated into four layers. They lie horizontally on top of each other, separated by an undefined space. The edges of the layers are said to be rotting and rather fragile, so when you walk in the said place, your feet will sink into the ground. The edges of layers are also mysterious, magical places where the supernatural occurs, and the spirits manifest in dangerous ways. The highest layer is called Duka Kä Misi. This layer is empty at the moment, but many things originated there and fell down through the layers. Despite being the highest level, where as in most religions it would serve as some sort of heaven or nirvana, this layer has no significance in Yanomamö life, as if it has fulfilled its purpose. The layer underneath is called Hedu Kä Misi. The top of this layer is invisible, but it is said to be ‘similar to earth’, in that there are trees, animals and the souls of deceased Yanomamö. The souls of the deceased do all the things the living do – hunting, gardening, making love, practicing witchcraft, etc. Everything that exists on earth has a counterpart on this layer, much like the western idea of a parallel world. The underside of the Hedu Kä Misi is the sky that we can see. The stars and planets are attached to the bottom and move across it on their own individual journeys. Some of the yanomami people believe that the stars and planets are actually fish in the sky, but there is no proper astronomy, no constellations or star names. This layer overall is considered to be quite close to the earth, as many anthropologists have been asked if they’ve bumped into the layer when they flew in planes. The Hei Kä Misi is the earth layer, the layer that the Yanomamö and others live on. This layer was created when a piece of Hedu Kä Misi fell down. This layer contains all the animals, jungles, people, etc. The Yanomamö believe that all the other people are just degenerate copies of themselves. The lowest layer is the Hei Ta Bebi. This layer is almost barren, and there are variants of the Yanomamö people living on this layer called the Amahiri-teri. They originated when a piece of Hedu Kä Misi broke off and knocked a village from the Hei Kä Misi down. Only the village was knocked down, however, no animals or plants, so they turned into cannibals. They send their souls up to this layer and steal children’s souls, which are brought back down and eaten. In some villages, shamans regularly fight off the spirits of the Amahiri-teri. The Amahiri-teri were also around at the time of the No Bababo. The No Bababo are where the Yanomamö themselves originated. These people are different from the modern Yanomami in that they were part spirit, part animal and part human. When the No Bababo died, they turned into the spirits known as ‘Hekura’. These are the spirits that the shamans communicate with. Hekura are very, very small – no bigger than a couple of inches. Male hekura have a halo known as a ‘Wadoshe’, and female hekura have wands coming out of their vaginas. Each hekura is amazingly beautiful, and they all have different personalities and characteristics. Some hekura are able to attack human souls with weapons, or by being hot and burning them. Some are even cannibalistic. These are the spirits that the shamans send out to hurt their enemies. The shamans communicate with the hekura spirits by first summoning them into their chests. The Yanomami believe that inside a shaman there is a mini-cosmos so that the hekura can stay there comfortably. The shamans use the hekura to heal their sick and to attack their enemies. Only men can become shamans, and there is usually quite a high percentage of shamans in a village. To train as a shaman, a man must fast for at least a year, and during this period he must abstain from sex as the hekura are repulsed by it and regard it as ‘filthy’. However, once this period is over, the men can have as much sex and food as they like. It has been suggested by anthropologists that the reason for this period is to reduce sexual jealously in the village, and also to give the older men a chance to copulate. Ebene is the hallucinogenic sniff taken by the shamans in order to contact the hekura. They are also more likely to attract hekura by painting themselves and decorating themselves with feathers, as hekura are beauty enthusiasts. As the ebene takes effect, the shamans chant tales of creation and legends louder and louder. This is a daily occurrence as the shamans feel it is important to pass down the knowledge from generation to generation. However, ebene also has downsides, as most drugs do. Some men take ebene just to get a high, and sometimes ‘freak out’ – releasing suppressed emotions and doing things that would be highly taboo while sober. Ebene users often vomit and also have trails of green slime hanging out of their noses, which they leave on their bodies as the hekura can see it. The Yanomamö have many myths and legends passed down via word of mouth. One myth, which has been compared to Christian myths, is when a great flood rushed through the village, and a few of the Yanomami survived by clinging onto floating logs. They were swept downstream and presumed dead. The people returned later, floating on canoes and speaking ‘crookedly’. The people said a great spirit called Omawa rescued them, wrung them out and brought them back to life. The Yamomamö don’t have a concept of the perfect afterlife, like nirvana or heaven, but they believe that when they die they repeat life on the layer Hedu Kä Misi. Systems of Knowledge and Moral Systems Marriage The Yanomamo people are a polygamist society and have strict rules on which they can and can’t marry. They can marry Male: the daughter of their father’s sister Female: the son of their mother’s brother They can’t marry Male: the daughter of their mother’s sister Female: the son of their father’s brother Wives amongst the Yanomamo people also leads to warfare because of the violent nature of the men towards their wives some of them get killed and in the majority of cases they get stolen by neighbouring tribes which leads to war. Classification Systems/Taboo The Yanomamo people don’t think very highly of strangers and often accuse them of the act of cannibalism when one of their people either go missing or get killed. Canniblism for the Yanomami is seen as a crime only punishable by death. This is ironic however because they believe that death itself is caused by evil spirits eating your soul. When one of their tribe dies, they then cremate their dead, then crush and drink their bones in a final ceremony intended to keep their loved ones with them forever. For a Yanomami, a stranger is anyone that doesn’t belong to their socio-cultural world mixed blood and whites, all of whom are grouped together into the same category of “creatures that deserve no respect”. They call these strangers “nabe”. Justice The Yanomamo people don’t have much of an opinion where justice is concerned however as warfare is such a major part of their lifestyle many contributing factors can lead to war which they themselves believe is justifiable. If someone from a neighbouring tribe was to steal a part of their family, their weapons or their food for example, the Yanomami would think if perfectly justifiable to then go to war with those people. This also leads to them having very few good ties with other tribes as they are constantly starting feuds and wars. Honour and Shame “Marriages are often arranged according to performances of one's relatives in battles.” So the constant fear of death present in Yanomamo culture does not constrain their enthusiasm or effort in battle; the fact that marriages can be dictated by it would also suggest that there is honour in fighting and fighting well. Pride and family honour amongst tribes can be the catalyst for arguments and fights amongst their male members. Every member of each tribe takes pride in belonging to the group – could this be demonstrated in their fighting? Or is fighting truly just a necessity? “It is not simply 'ritualistic' war: at least one-fourth of all adult males die violently.” “Napoleon Chagnon When men go off to war, they wear black body paint, which symbolizes the night and death. When in mourning, a woman wears black paint on her cheeks for an entire year before she can use red again. For some festivals, the Yanomami apply white clay over the body. Good and Evil “What I have found belongs to me.” common law within Yanomami society, much like the Western children’s phrase “finders keepers!” “I recalled what Jose Jad told me before. But the Indians did not touch anything without making sure - even if it was just a glance - that we wouldn't mind it. (if they know something is already owned…) “Indeed, they opened the torch, unscrewing it with slow, quiet movements, checking what was inside it. They tried my hat, sprayed themselves with a mosquito repellent but the ring aroused the greatest curiosity. I had to tell them though that taking it off my finger was a bad sign and a taboo. They nodded with understanding and never asked again.” Purity and Impurity The endogamous marriage to someone who is not a cross cousin – e.g. merely a cousin – is impure. Disease or illness could be viewed as impure in the village shaman’s enlistment of ‘good spirits’ to fight the ‘evil spirits’ (shawara) that have taken residence in the patient’s body using yakoana, a hallucinogenic herbal powder. Relationships with the Environment The Yanomamo people rely on the environment to supply them with everything they need to live. Their Shabono (large round hut with an open centre) is built from leaves, vines and tree trunks but is therefore easily damaged by strong weather. Very knowledgeable about areas most suitable for villages. Their main food source is plantain that they grow in their “gardens”, but they also hunt for fish and animals. They believe in Shifting Cultivation to ensure that areas do not become overused. “Slash-and-burn” horticulture is used to make the ground more fertile. The arrival of missionaries has impacted the nature balance due to their more effective hunting techniques. They are one of the most successful groups in the Amazon rain forest to gain a superior balance and harmony with their environment. David Yanomami (one of the Amazon's most respected "Page" or Medicine men) foretells that if the white man does not stop his perverse destruction of our Mother Earth, that the white men are doomed to extinction, right along with the rain forest and the Yanomami. They believe that their fate, and the fate of all people, is inescapably linked to the fate of the environment; with its destruction, humanity is committing suicide. “Nature creates everything, and is sacred.” “The authorities in Venezuela and Brazil knew very little about their existence until anthropologists began going there. The remarkable thing about the tribe, known as the Yanomamo, is the fact that they have managed, due to their isolation in a remote corner of Amazonia, to retain their native pattern of warfare and political integrity without interference from the outside world. They have remained sovereign and in complete control of their own destiny up until a few years ago. The remotest, uncontacted villages are still living under those conditions.” Napoleon Chagnon Globalisation – Missionaries Missionaries have greatly altered Yanomamo life; they have introduced Christianity and modern languages like Spanish. Western devices like guns have been acquired through missionaries and so warfare has become more dangerous. The missionaries have attracted global attention to the Yanomamo and so visitors are common, bringing with them diseases that attack the Yanomamo. Many villages rely on the mission stations for medicine and have accepted that there are other healing methods than their traditional ones. 1980's - The Gold Rush The Yanomami had very little contact with the outside world until the 1980's. Since 1987, the Yanomami have seen about 10% of their entire population - over 2,000 people - decimated by massacres and diseases brought by invaders. The Yanomami are the most well known and best documented of the four divisions partly because they have been victims of a recent gold rush. After gold was discovered on Yanomami land in the mid-1980's, thousands of miners illegally rushed into the territory. The constant flights of supply planes and the noise from generators and pumps used in the mining operation has frightened away the game animals the Indians rely on as a key source of protein in their diet. High pressure hoses are used to wash away river banks, silting the rivers and destroying spawning grounds. Mercury is used to separate the gold from soil and rock. It is then dumped in the rivers haphazardly. Mercury bio-accumulates and reeks havoc on the entire ecosystem. The effects of mercury poisoning reach even the surrounding trees, some of which rely on birds and fish to disperse their seeds. The mercury ascends the food chain up to the Yanomami in the form of a neurotoxin that especially affects child development. The most devastating statistic of them all: child mortality rates have skyrocketed while birth rates have declined. The influence of the miners goes well beyond physical health. They introduce alcohol outside of ritual which exacerbates existing rivalries and leads to violence. Weakened by illness and unable to produce and hunt enough food, the Yanomami are reduced to begging and most recently trading sex for food. For the Yanomami what was once an intricate social system patterned on trading and bartering goods and food amongst themselves has become a game of deadly high stakes where they are trading their culture for their very existence. The effects are dire. Disoriented by the influx of miners with their unfamiliar culture, technology and diseases, their self-respect has plummeted as their belief and cultural systems are undermined. The Yanomami are not being integrated into Western society; instead begging, prostitution and drunkenness are being introduced into theirs. In 1992, the Yanomami Territory was demarcated and ratified, yet the government has not consistently kept its commitment to protect their land. Supported by politicians and business people, the gold miners assault escalated. In July 1993, a group of miners tried to exterminate the village of Haximu, killing 16 Yanomami, in what Brazilian Attorney General Aristides Junqueira classified as genocide. Despite international outcry spurred by the massacre, miners continue to enter the territory illegally. According to the Commission for the Creation of the Yanomami Park (CCPY) in Sao Paulo and the Indianist Missionary Council (CIMI) in Brasilia, state and local politicians are fighting to reduce the Yanomami territory because they want access to its rich mineral deposits. There is little question that if this happens, the gold prospectors will be replaced by large scale commercial mining operations that will only compound the devastation of the Yanomami and the rainforest. Interaction, Media and Communication With more tourists and missionaries arriving, the Yanomamo people are coming into contact with outsiders more and more. Airstrips and houses have been built for these visitors. Missionaries allow visiting groups due to large cash gifts intended to help their work. There are still some groups that choose not to have any contact with missionaries but these are scarce as many see them as a benefit. Contact between villages is common including negative contact like warfare. Enemy villages and war keep them apart, but alliances and a descent from common ancestors tends to reduce the distances. Arts and Expression The women weave and decorate baskets. They make both flat baskets and burden baskets, which are carried by a strap around the forehead. These they dye with a red berry called Onoto that they also use to decorate their bodies and dye their loin cloths. The baskets are then decorated with traditional geometric designs with masticated charcoal pigment. The women also make necklaces which they then wear. Yanomamo women will also paint their scars from their husbands’ beatings red as they believe that they are a sign of their husbands’ love and so they are very proud of them. While in the past pottery was an important artisan craft in Yanomami culture, today it has almost completely disappeared. Few communities still make the typical Hapoka, a plain bell-shaped pot made with white clay. Singing and dancing is common at funerals and also when taking the drug Ebene, as they believe that it lures the Hekura spirits into their bodies and so will do their bidding. In the ‘dry season’ Yanomamo often visit other tribes, to feast, to trade and to assure their political alliances. Wives are often given in exchange for goods needed by one village to another. The distance between villages may vary from a few hours walk to a ten-day walk. Warring villages are usually several days walk from each other; where as tranquil ones may be less than a day away. THE YĄNOMAMÖ SOCIETIES AND CULTURES IN CONTACT The Yąnomamö are a people who, until recent decades, had very little contact with ‘the outside world’. Some, when asked where Brazil and Venezuela are situated, had no idea and even thought that they were entirely different countries from their own, and unrelated to their culture. As a result they never were forced to move from their habitat, they were never colonised, they never had any tourists, they never needed to resist any globalisation etc. Indeed, there has also never been such a thing among them as genocide or ethnocide. Yet this has changed entirely in the past 40 years for a number of reasons. The main reason is the missionaries that are stationed near some settlements, but also because anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon’s work has been spread across the academic world and the Yąnomamö have been subject to much discussion, and the world is no longer ignorant of their existence. Education and awareness of the ‘outside world’ Education had never previously existed among the Yąnomamö, but children at Bisaasi-teri (a type of ‘alliance’ of 12 villages) now go to school regularly, thanks to the nearby missionaries. They follow the Venezuelan school calendar and now Yąnomamö people are becoming more aware of weekdays and holidays, both being concepts which previously were not known to them. Spanish words are infiltrating the Yąnomamö language and words such as vacación (holiday) are being used regularly. Fluency in Spanish is increasing due to many children going to Mission School and now great proficiency in reading and writing Yąnomamö is ensuing. This is a very significant detail because westerners have developed a written form of an illiterate language (using the Latin alphabet with diacritics). Napoleon Chagnon recounts, in his Yąnomamö monograph1, how one of his Yąnomamö friends read, over his shoulder, some of the genealogical information on his computer, upon Chagnon’s return after a 10 year absence from Yąnomamöland, and how the anthropologist was not expecting such a drastic change in intellect and education. They learn a lot about western society and even western concepts, such as a school bus system, are being used: they use a large dugout canoe which goes to all 12 villages in Bisaasi-teri every morning to pick up all the children and, in the evening, takes them all back home. Chagnon describes how one Yąnomamö questioned him about the atomic bomb; also some tribesmen discussed with him the film ‘Jaws!’. Western culture is being taught to Yąnomamö people. All of this, however, is only relevant to villages near missionary bases. More remote villages are much less affected by mission intervention. When a concept is passed from mission villages to remote villages, the concept is simplified so that the ‘remote people’ can understand it. For example mission-educated Yąnomamö have been taught about garimpeiros, who are Brazilian gold miners. They use mercury to extract gold from the soil and the mercury residue subsequently gets washed into the rivers, poisoning the wildlife. They have never seen this in action but they can understand the principle. When this is Yaņomamö, Fifth Edition – Napoleon A Chagnon. Published 1997, Harcourt Brace & Company. pp. 251252 1 passed on to remote villages, the concept is translated to: the enemy uses a special form of poison (oka, the Yąnomamö word for this magical poison) to put in our rivers to kill us. The enemy is thought of usually as people from a (fictional) village called Garibero (which sounds vaguely like garimpeiro). But the problem of globalisation here is smaller, because the concept has been simplified into their own realms of understanding, thus not really affecting them at all (especially taking into consideration the fact that such remote villages will never come into contact with garimpeiros). Dangers of globalisation and contact with the ‘outside world’ Of course, if a Yąnomamö somehow finds his way to a city, his behaviour will perhaps not be very well accepted, for many reasons: he would not be wearing what Venezuelans would call decent clothing; his treatment towards others may be seen as unusual etc. This is not the main problem. There is no danger in this form of globalisation and integration. A very dangerous and destructive trait of globalisation is the availability of shotguns and machetes among Yąnomamö people. They are very, very cheap in Brazil, and they can be easily taken off missions in Venezuela. In both countries do many Yąnomamö possess shotguns and machetes. Of course, this is a great danger when battle strikes, because the intracultural death toll will increase, but another danger (perhaps a less-common one) is also coterminous therewith: Chagnon repeats the story of a shotgun-wielding Yąnomamö, and how he ran to a far-away village (one with which his village never previously had any contact) and killed a man with his weapon. Upon questioning Rewebawä about why this was done, he got the reply “If you give a fierce Yąnomamö man a shotgun, he will want to use it to kill with – simply because he has it.”2 Other dangers of contact from outsiders are to do with health. Chagnon’s mortality rate graph3 describes the death rates in three different kinds of villages over a four-year period. The three village types are: ‘Maximum Contact’, which applies to villages at mission posts, thus people have maximum contact with outsiders; ‘Minimum Contact’, implying villages where missions only sporadically visit; and ‘Intermediate Contact’, which are villages which are reachable by motorised boats and, perhaps, a subsequent short walk, from mission stations. The graph shows that circa 5 percent of the population in ‘Maximum Contact’ villages died during those four years, circa 6.5 percent in ‘Minimum Contact’ villages and circa 19 percent in ‘Intermediate Contact’ villages. This evidence suggests that the ‘Maximum Contact’ villages have the lowest death toll because of western intervention and healthcare (and also because most of them have been in contact with the ‘outside world’ for more than 30 years, and so the effects of contact have worn away somewhat); the ‘Minimum Contact’ villages have a slightly higher death toll, which, it seems, is a normal Yąnomamö village death toll; and the ‘Intermediate Contact’ villages have the highest because they have enough irregular contact to receive western sicknesses, but live too far away so that they may die before word of their sickness reaches the missions and help is provided (that is to say if help arrives at all – during the 1992 epidemic in intermediate village Kedebaböwei-teri, no help came from anybody, although the Salesian missions claimed to have heard ‘rumours’ that they were sick); also they receive pollution dumped into their rivers from upstream mission stations – perhaps poisoning the water or simply adding broken glass to the riverbed, 2 3 Yaņomamö, Fifth Edition – Napoleon A Chagnon. Published 1997, Harcourt Brace & Company. pp. 228 Yaņomamö, Fifth Edition – Napoleon A Chagnon. Published 1997, Harcourt Brace & Company. pp. 246 making it likely to pierce one’s feet when stepping into the water (which may subsequently cause infection). Conservation and culmination Land and health seem to be the two most important needs for the survival of the Yąnomamö people. In Venezuela, the government has decreed that the Yąnomamö are the rulers of their territory and have the right to forbid economic development in their habitat. In Brazil most of their territory has been named a nature reserve and so nothing may be built thereupon. Chagnon tries not to affect or westernise Yąnomamö culture, yet because Occidentals have introduced new illnesses to their culture, he feels obligated to treat them with western medicine. Other than this, Chagnon has not particularly intervened with their culture. Yet, despite the efforts made by the government to conserve the habitat of the Yąnomamö, it is inevitable that westernisation will continue: now that the west has stationed missionaries in Yąnomamöland; diseases have been brought in, causing more contact with western health professionals; some villages have come into a lot of contact with the ‘outside world’; education has been established among many villages; and westerners are becoming much more aware of Yąnomamö doings, the chances of globalisation are very high. There is a mixed opinion, nonetheless, about whether westernisation of Yąnomamö culture is right or not: some feel that it is a very good idea because their quality of life, arguably, is poor. They live in poverty. Others think differently and think more of resistance to globalisation. It is likely that, in several decades’ time, there will be a revitalisation of Yąnomamö culture, for fear of its total extinction.