Contract Law 8 PowerPoint

Contents of the contract – Terms

Terms of the contract are generally thought of in one of 3 categories: i.

Conditions ii.

Warranties iii.

Innominate or intermediate terms

Conditions and warranties

A condition – is a term that is regarded as being FUNDAMENTAL to the contract because it goes to the ‘root’ of the contract.

A warranty – is a less important term of the contract

Contrasting cases

There are 2 cases to show the difference between conditions and warranties:

Poussard v Spiers 1876 and

Bettini v Gye 1876

Conditions

A term in a contract may be designated as a condition by 3 methods: i.

By statute – for instance, by the Sale of Goods

Act 1979 ii. By the courts – as in the Poussard v Spiers case iii. By the parties themselves by using the word condition, so long as the court is sure that both parties intended to mean condition in this sense

Innominate terms

The ‘innominate’ term – did not come into being until 1962 in the case of

Hong Kong Fir Shipping Co Ltd v

Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha Ltd 1962.

Terms of the contract

A term in a contract may be held to be in the contract either because:

• - it was put there EXPRESSLY by the parties or

- it has been IMPLIED into the contract by various methods

Express terms in contracts

For WRITTEN contracts there are various things to consider.

i.

the Parol Evidence rule ii.

whether a pre-contractual statement can be regarded as a term iii.

signed written documents iv. whether terms written in various documents can be v.

incorporated as terms of the final contract, and finally vi. whether terms have been incorporated into the contract by virtue of a consistent course of dealing over time

Parol evidence rule

The parol evidence rule has been discussed in a previous lecture.

The rule is basically that if the parties have put their contract into a WRITTEN document, then they cannot later bring in EXTERNAL evidence to ADD TO,

VARY or CONTRADICT the written contract.

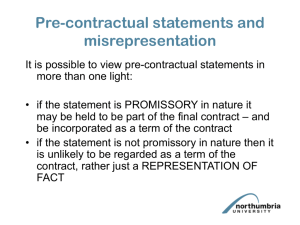

Pre-contractual statements

If one or more pre-contractual statements are regarded by the court as part of the final contract, because they display an element of futurity and so are seen to embody a promise, then they are regarded as express terms.

L’Estrange v Graucob 1934

If one or more pre-contractual statements are regarded by the court as part of the final contract, because they display an element of futurity and so are seen to embody a promise, then they are regarded as express terms.

L’Estrange v Graucob 1934

The plaintiff had bought a cigarette vending machine from the defendant. She signed an order form which contained a broad exemption clause in very small print. The machine did not work and she brought an action for breach of an implied warranty in the contract that the machine was fit for the purpose it had been sold for.

The court found for the defendants on the basis that she had actually signed the contract containing the exemption clause and so it was her fault if she had not read it.

Curtis v Chemical Cleaning and Dyeing Co Ltd 1951

When the dress was returned with a stain on it the plaintiff sued the company who tried to rely on an exemption clause. It was held the exemption clause only applied as regards the beads and sequins and not as regards stains because of the misrepresentation to the plaintiff that only liability re beads and sequins was excluded.

Non-est factum

If successfully pleaded, the contract is held to be void – it never existed.

This could have a harsh result where an innocent THIRD PARTY is the beneficiary under the contract who would suffer loss if the contract was held to be void due to non est factum.

An illustrative case is Saunders v Anglia

Building Society 1971.

Grogan v Robin Meredith

Plant Hire 1996

On Appeal to the Court of Appeal,

Auld LJ stated:

‘I reject Mr Turner’s proposition that the court should look only at the

WORDS of a signed document and disregard its nature or function…The central question is … whether the document purported to have contractual effect… Documents such as a time sheet, an invoice or a statement of account… do not normally have a contractual effect in the sense of making or varying a contract. The purpose of time sheets is not normally to contain or evidence the ‘terms’ of a contract, but to

‘record’ a party’s ‘performance’ of an existing obligation under a contract.’

Incorporation of written terms

Three key points here seem to be:

Firstly, the timing of when the document is brought to the attention of the other party

Secondly, the nature of the document – as we saw in the

Grogan case, some documents, such as timesheets, invoices etc, usually only evidence the administration of the contract without becoming ‘part’ of it

Thirdly, whether or not the other party was given ‘reasonable notice’ of the terms alleged to be in the contract

Incorporated or not?

The timing of when the document is brought to the attention of the other party, an interesting case is:

Olley v Marlborough Court Ltd 1949

Incorporated or not?

Nature of the document

We have already looked at the Grogan case to help with the nature of the document and noticed that some documents are merely part of the ‘administering’ of the contract.

Chapelton v Barry UDC 1940 demonstrates the nature of the document and the timing of notice.

Incorporated or not?

Giving reasonable notice

What amounts to reasonable steps will be decided on the facts and circumstances of each individual case.

An interesting case is:

Thompson v London, Midland and

Scottish Railway 1930

Incorporated or not?

In Parker v South Eastern Ry Co 1877 the plaintiff lost his action because his attention had been drawn to the cloakroom ticket on which it said on the front, ‘See Back’. On the back it limited the railway company’s liability to £10 and so the plaintiff could only recover

£10 even though the contents of his bag were worth more than £10.

Cases not involving exclusion clauses

An interesting case is

Interfoto Picture Library Ltd v Stiletto

Visual Programmes Ltd 1989

Consistent course of dealing and common knowledge

When the two parties deal with each other regularly on standard terms and conditions, then so long as they have dealt ‘consistently’ previously, the terms and conditions will become part of the contract between them if on the one occasion they omit to use the standard form.

See McCutcheon v David MacBrayne Ltd 1964

Update September 2008

Judges have made use of the rules of whether or not a written term has been incorporated into a contract as a method of controlling the number of unfair terms in a contract. These rules would be unnecessary if judges had the power to exclude unreasonable terms generally in the contract besides the exclusion of unreasonable exclusion clauses.